"I took him in like he was my own son. I felt sorry for him when I saw him, he was so small. Then he told me that he was from Papua New Guinea, didn't have any family and was here for four months. My heart went out to him and I told him this is your home. You can call me nene and these are your brothers and sisters. He spoke in broken English, ate what we ate and was easy to live with."

Mrs Rauge Naikeli, Namotomoto Village, Nadi

The mystery of the Iranian refugee continues:

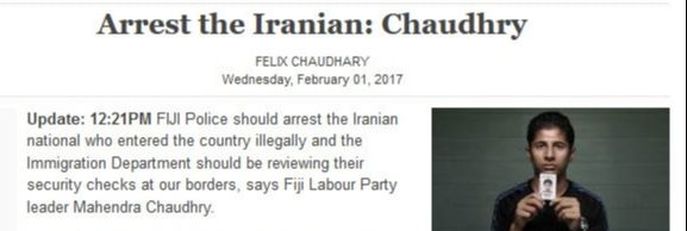

Now that the guy who claimed to be an Iranian national seeking refugee status in Fiji has been deported to PNG after being nabbed at Korolevu, questions remain about the incident. According to the Fiji Sun he was staying with a family in Nadi while hiding from Immigration authorities. This raises further questions:

1. He obviously had a contact in Nadi who gave him sanctuary. Who is this Fiji link? Do the authorities know the identity of this person/family that took him in and kept him in hiding from the authorities for a week? We know from pictures that he had found refuge somewhere near Wailoaloa Beach and was obviously well looked after.

2. Has this Fiji link been questioned? Because for all we know there could be quite a regular racket going on in human trafficking that the Fiji authorities may not know of?

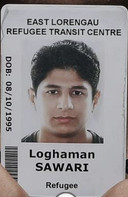

3. Why did it take a week for Immigration to nab the so-called Iranian – in fact, not until political parties began posing questions in the Fiji media about the strange case of Loghman Sawari, if that is his true name?

4. Why are the authorities not coming clean about this whole affair? The public of Fiji are entitled to the truth regarding Loghman Sawari and his Fiji connections. Instructions are that all questions regarding the affair are to be directed to the Prime Minister’s Office and not to Immigration authorities. Strange indeed! Well, how about a statement from the PM’s office?

I really miss him, says Sawari aider

By Felix Chaudhary And Margaret Wise

The Fiji Times

Saturday, 4 February 2017

These were the words of an emotional Nadi mother as she related last night how Loghman Sawari arrived at her Namotomoto home almost two weeks ago

.

The Iranian national was brought to her door by her 12-year-old son, Isimeli.

Both were teary-eyed, distraught about yesterday's deportation of the 21-year-old.

"I really miss him, he cut my hair and cooked meals for us, he was a nice man," the young boy said.

Rauga Naikeli said she was ironing clothes about two weeks ago when her son arrived with Mr Sawari.

"They met on the roadside and Loghman asked him to help search for a place to stay because the hotel he was staying in was too expensive," she said.

"They went around looking and couldn't find appropriate accommodation, so Isimeli brought him home and asked if he could live with us.

"I felt sorry for him when I saw him, he was so small.

"Then he told me that he was from Papua New Guinea, didn't have any family and was here for four months.

"My heart went out to him and I told him this is your home. You can call me nene and these are your brothers and sisters. He spoke in broken English, ate what we ate and was easy to live with."

Ms Naikeli said the Iranian told them his name was Junior and it wasn't until a few days later that he told them about his life in detention and as a refugee in PNG.

"He showed me his PNG passport and it had his name Loghman Sawari in it.

"I was really moved by the story of the loss of his family and the suffering he had experienced on the streets of PNG.

"I told him that he should immediately go to immigration and seek advice on what he could do.

"He left the next day for Suva and returned three days later.

"Loghman informed us that he had a lawyer."

Ms Naikeli said when she later read in the news that the Immigration Department was still waiting for him she scolded him. "But he said his lawyer was handling everything and we left it at that.

"He left home on Thursday and we knew that he was meeting the immigration officials yesterday.

"We were waiting and hoping for some good news because we really felt sorry for him. He had become part of my family.

"When we heard that he had been arrested and deported we were all devastated.

"We had all grown attached to him and had so much love and compassion for him because of the experiences he said he had been through."

Sawari was among 60 detainees who spent three weeks in the East Lorengau jail in PNG after protesting against their indefinite detention. As Sawari tells it, his crime was to be among those who chanted ‘Freedom!’ “He handcuff me and send me to the jail for 21 days.” “The security guard say, ‘You want freedom?’ I tell him yes. He handcuff me and send me to the jail for 21 days.”...Sawari still suffers depression but retains the capacity to hope for a happy ending. “Everyday I pray, ‘Please god, not only help me, help everyone’,” he says.

He was 17 when he arrived in Papua New Guinea in August 2013, one month after the then Labor government decided to remove children and family groups from the detention centre.

He has the letter from Australian immigration officials confirming his age and telling him he would be “treated as a minor for the purposes of accommodation, placement and other purposes”.

He remained in isolation until his 18th birthday, when he was told he would be staying. The smug expression on the face of the official who conveyed this news is etched in his memory.

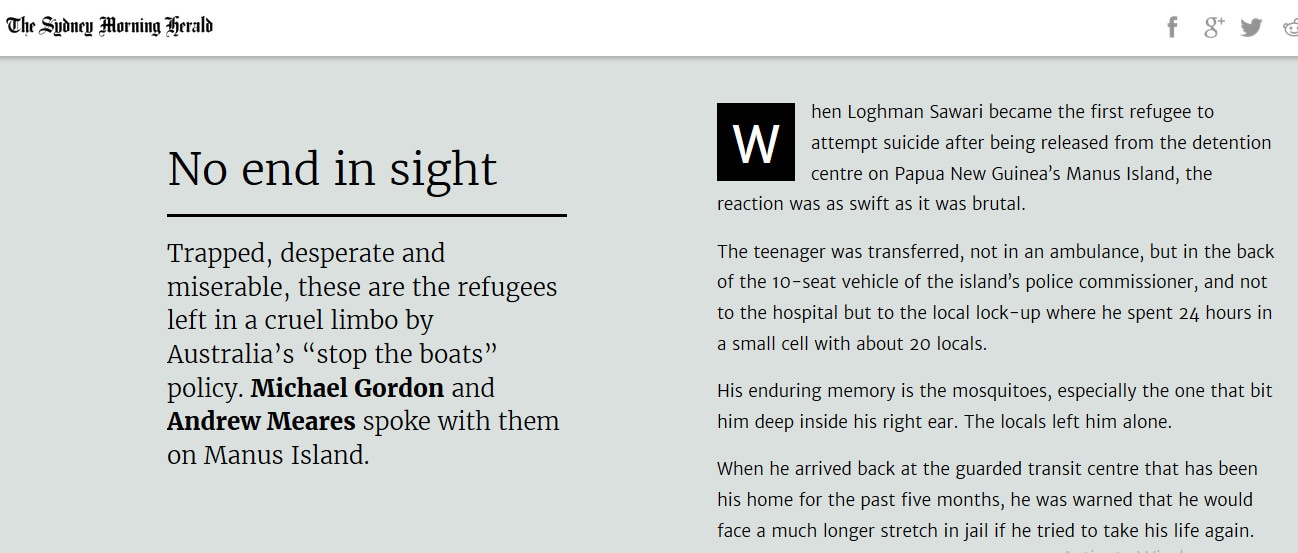

Now he is a contradiction: a certified refugee who tried to take his life after finally being given the recognition that asylum seekers crave, the status that differentiates those found to be owed protection and the opportunity to rebuild shattered lives from the rest. It isn’t supposed to work that way.

What compelled the 19-year-old to turn a towel into a makeshift noose, attach it to a rafter outside his room and step from a chair to oblivion is hardly a mystery. His bottom lip trembles uncontrollably as he tries to explain that anger, despair and an all-consuming sense of hopelessness propelled him.

Anger at the local immigration officer who, he says, incited him to go ahead when, out of frustration, Sawari told the officer he planned to kill himself. With calculated indifference, he says the officer replied that he was free now to do whatever he liked.

Despair that the prospect of seeing the mother he misses desperately is as distant now at it was when he was first taken to Manus against his will from Christmas Island. He has been told he will have to wait eight years to either travel to see his mother or sponsor her to join him. “If I wait for eight years, maybe my mum die. Maybe I die. This is not good.”

And hopelessness, because each day passes so slowly he says it feels like a year. Tablet-induced sleep offers the only respite, except when it leads to the recurring nightmare that terrifies him, where five menacing dogs stand before him, and the biggest one is jet black and demands money he doesn’t have.

When the lightly framed Sawari arrived at the transit accommodation in April, there were only 12 other residents. Now there are more than 50 others in the same situation: recognised as refugees, but denied almost all the basic rights that are supposed to come with refugee status.They cannot earn a living, learn, move freely, buy property or be reunited with family members.

Sawari hurt his arm recently when he says he was punched by a security guard after asking for an extra cake of soap. The doctor gave him a prescription to address the pain, but he could not afford to fill it and still buy enough credit to ring his mother, who believes he is living happily in Australia.

Sawari’s first taste of the heavy hand of those who run the detention centre came soon after he arrived, when he spent two months in isolation with three other teenagers. He believes two returned to their country and one is living in Adelaide.

At one point he threatened to hurt himself if he was not able to join his friends in one of the big compounds. He says he wasn’t serious, just depressed and lonely. Within 30 minutes, 10 security guards arrested him before he had time pull on his shoes. At the police station, they ordered him to strip naked to show he was not carrying a weapon before immigration officials delivered an ultimatum: “If you don’t promise to be a good boy, we will leave you here.”

When he returned to the compound, having promised to be a “good boy”, the door of Sawari’s room was replaced with a curtain so he could be monitored. “I was sitting in the rain, crying. The guards from G4S (since replaced by Wilson Security) were laughing at me.”

A year after the violence, Sawari was among 60 detainees who spent three weeks in the East Lorengau jail after protesting against their indefinite detention. As Sawari tells it, his crime was to be among those who chanted ‘Freedom!’

“He handcuff me and send me to the jail for 21 days.”

“The security guard say, ‘You want freedom?’ I tell him yes. He handcuff me and send me to the jail for 21 days.” What made the experience more traumatic was that two of Barati’s alleged killers were being held at the jail at the same time.

Immediately after Sawari’s suicide attempt, three months ago, one of the other refugees confronted the immigration officer who had upset him. “Why you provoke him to kill himself? He’s a young person. How do you answer to his family if he die?” Mohsen, a 28-year-old Iranian refugee who dreams of studying art, recalls saying.

The response, he says, was the stock answer to any complaint: “If you have a problem, go back to your country.”