Fact Sheet: March 24, 2021 | The United States accepted in whole or in part 280 out of 347 recommendations it received from other UN Member States during the third cycle UPR, or approximately 81%. Acting DRL Assistant Secretary Lisa Peterson delivered remarks via pre-recorded video, outlining the U.S. approach to the recommendations received and further explaining the Biden Administration’s priorities on racial justice, nondiscrimination, migration, climate change, and COVID-19 response, among others. |

Fijileaks: Raj had set out with our current Founding Editor-in-Chief and others in opposing coups and the gross racial discrimination in Fiji but along the way, sadly, sold his soul for few pieces of silver, jumping ship. He is, we are told, a pleasant bloke but flawed individual when it comes to issues of human rights violations in Bainimarama's Fiji. We suspect that like Aiyaz Khaiyum, his experiences of the maltreatment of Indo-Fijians has made him blind to the wider human rights issues in Fiji

BALD MORAL COMPASS: Aiyaz Khaiyum's 2013 Constitution of Fiji prohibits the FHRC from investigating cases filed by individuals and organizations relating to the 2006 coup and the 2009 abrogation of the 1997 constitution. If he had any MORAL PLATEAU (whatever it means), he would never have applied to lead the FHRC. By applying, and then accepting the directorship, he is basically COMPLICIT in protecting the 2006 coup abusers and the 2009 abrogators of 1997 Constitution

Fijileaks to Raj: Can you explain in SIMPLE ENGLISH, please!

WHEN will you produce the 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 Fiji Human Rights Commission Financial Reports? Raj says neither his comatose FHRC nor the dictatorial FFP government was consulted on the 2020 US Human Rights Report on Fiji. The loud mouth and unintelligble Fiji's Benito Mussolini must be aware that the United States never consults the countries on which it reports, and the annual reports are in the same format on all the countries. So, Fiji is no exception. In fact, FIJI comes out far better when compared with many of these countries. Basically, he is barking mad at the US after Bainimarama was snubbed by President Joe Biden on the forthcoming Climate Meeting. How best to get into his hollow head. What the US Embassy in Fiji informed Washington was that Raj was very quick to sacrifice a few police, military, and prison officers but generally, when it came to those politically opposed to FFP policies and bills, there was deafening silence on his part, prompting charges that he was perceived to be pro-government - Regime LACKEY!

"There was neither any consultations with the state and independent institutions including the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission in the formulation of this report nor any ethic of constructive engagement over the years, as far as the HRADC is concerned, in relation to human rights in Fiji." Ashiwn Raj.

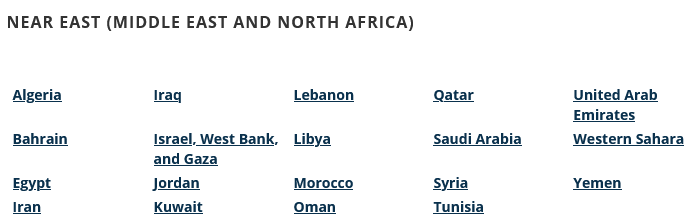

Just imagine if the United States sent to all these countries listed below for comments on US reading of human rights in their countries? There would, simply, be no annual reports. In fact, FIJI comes out far better when compared with many of these countries. So, RAJ, just shut up and speak up for the Fijian taxpayers who are paying your salary. The US Annual Reports are in the same standard format for all the countries.

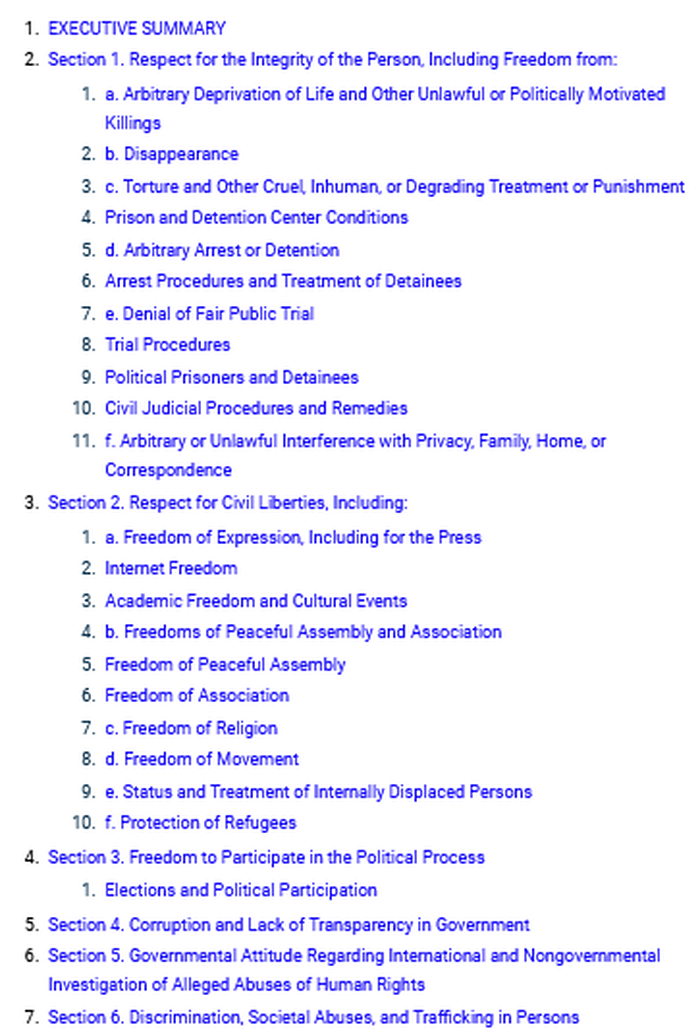

The 2020 US COUNTRY REPORTS ON:

The US2020 Human Rights Report on Government Human Rights Bodies

Australia's Human Rights Commission: The Human Rights Commission (HRC), an independent organization established by parliament, investigates complaints of discrimination or breaches of human rights under the federal laws that implement the country’s human rights treaty obligations. The HRC reports to parliament through the attorney general. Media and nongovernmental organizations deemed its reports accurate and reported them widely. Parliament has a Joint Committee on Human Rights, and federal law requires that a statement of compatibility with international human rights obligations accompany each new bill.

Fiji: Government Human Rights Bodies: The constitution establishes the FHRADC, and it continued to receive reports of human rights violations lodged by citizens. The constitution prohibits the commission from investigating cases filed by individuals and organizations relating to the 2006 coup and the 2009 abrogation of the 1997 constitution. While the commission routinely worked with the government to improve certain human rights matters (such as prisoner treatment), observers reported it generally declined to address politically sensitive human rights matters and typically took the government’s side in public statements, leading observers to assess the FHRADC as pro-government.

The 2020 report on human rights in Fiji issued by the US Department of State is perfunctory, scant in its interpretation and deconstruction of the law, saturated with generalisations and selective in its treatment of facts.

While the report impugns independent institutions like the judiciary and those responsible for the protection, promotion and preservation of human rights, there was neither any consultations with the state and independent institutions including the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission in the formulation of this report nor any ethic of constructive engagement over the years, as far as the HRADC is concerned, in relation to human rights in Fiji.

This does not mean that Fiji does not have any human rights challenges. We certainly do.

They include but by no means limited to sexual and gender based violence , torture and brutality at the hands of law enforcement agencies, rights of arrested and detained persons, racial and religious intolerance and hate speech, the need for constructive discussions on the right to peaceful assembly and the imperatives of public order and national security, the existential threat of climate change and the advent of COVID-19 and its attendant human rights challenges, and the need to ensure that the national human rights institution is compliant with the Paris Principles but Fiji continues to subject itself to scrutiny both domestically and at the highest human rights forums internationally, the most recent being the third cycle of its Universal Periodic Review at the Human Rights Council in Geneva.

Curiously the US State Department Report does not even make a cursory reference to Fiji’s UPR almost giving an impression that there is no accountability for human rights violations in Fiji, nor does it document our human rights achievements.

The US human rights record is hardly worthy of emulation but Fiji does not occupy an indomitable moral plateau with the compulsion to ritualistically produce a report on them every year. Given that the US jealously guards the right to free expression, or so it putatively claims, I will exercise mine and point out some of their human rights failings and the reason I raise these are because ironically some of these human rights failings form the basis of the report on Fiji.

This is a country that until recently had turned its back on the Paris Climate Agreement, had withdrawn from the UN Human Rights Council, placed sanctions against the International Criminal Court and has yet to ratify all core international human rights instruments.

These are Conventions on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, International Convention on the Protection, Convention on the Rights of the Child, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers, and Members of Their Families, International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

It has yet to establish an independent national human rights institution.

At the third cycle of its UPR, member states called on the USA to establish a moratorium on the death penalty, to put an end to life without parole sentence for juveniles, an end to arbitrary and indefinite detention, illegal and secret detention facilities, overcrowding in prisons, Police violence, use of excessive force and torture, racial profiling by law enforcement agencies, killing of civilians in military operations, gun violence, racism, extremism, xenophobia and hate speech directed at immigrants and asylum seekers, the adoption of punitive measures such as the incarceration of migrants and separation of migrant children from their parents to deter irregular entry and retrogressive policies that inhibit comprehensive and universal access to voluntary sexual and reproductive health services.

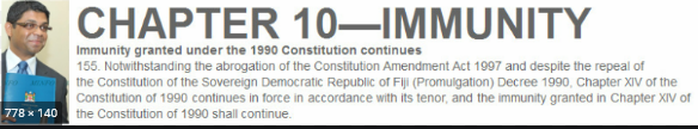

Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and immunity provisions in the Fijian Constitution

Just like the United States, Fiji is equally concerned with torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment and we have acknowledged this at home and internationally and the need for accountability without impunity for acts of egregious violations of human rights.

The claims about carte blanche immunity extended to security forces, however, is a distortion of the law and a complete misrepresentation of section 157 of the Fijian Constitution giving an impression that this provision is still being invoked in present day cases of torture and brutality to exonerate security forces.

While granting immunity to the President, the Prime Minister and Cabinet Ministers, Republic of Fiji Military Forces, Fiji Police Force, Fiji Corrections Service, Judiciary, public service and any public office from any criminal prosecution and from any civil or other liability in any court, tribunal or commission, in any proceeding including any legal, military, disciplinary or professional proceedings and from any order or judgement of any court, tribunal or commission, as a result of any direct or indirect participation, appointment or involvement in the Government from 5 December 2006 to the date of the first sitting of first Parliament elected after the commencement of this Constitution, section 157 of the Fijian Constitution expressly states “provided however any such immunity shall not apply to any act or omission that constitutes an offence under sections 133 to 146, 148 to 236, 288 to 351, 356 to 361, 364 to 374, and 377 to 386 of the Crimes Decree 2009”.

Absence of an independent oversight mechanism for the security forces

Quoting approvingly from a 2016 Amnesty International report, the State Department claims that “there is no independent oversight mechanism for the security forces”, “the legal framework means that no investigation can be initiated or disciplinary action taken against a Police officer without the consent or approval of the Police commissioner”, “authorized investigations were usually conducted by the Internal Affairs Unit, which reports to the Police commissioner, who decides the outcome of the complaint” and “information about the number of complaints, investigatory findings, and disciplinary action taken is not publicly available”.

This claim is misleading about the work of independent institutions such as the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission that independently investigates such matters and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions which sanctions charges.

Here are some examples of cases of torture and brutality investigated by the HRADC independently against the Fiji Police Force and Fiji Corrections Service (refer to table on page 5)

It is also imperative to note that information about the number of complaints, investigatory findings, and disciplinary action taken is available to the public.

The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions routinely releases statistics on serious crimes (sexual as well as non-sexual offences) on a monthly basis with cases and the outcome of the investigation resulting in charges.

This is available on their website and is also widely publicized by the mainstream media. Between 1 January to 31 December 2020, statistics from the ODPP show that a total of 20 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm in the course of arrest or in custody while 4 officers from the Fiji Corrections Services were charged with murder and assault.

The ODPP also in their release make available the nature of these offences.

Some of the examples include:

3 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm, acts intended to cause grievous harm to a 27-year-old man. Also charged with conspiracy to defeat justice and aiding and abetting. They allegedly assaulted a suspect with a concrete block and threw boiling water at him in the Police station.

2 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm to a 41-year-old man

5 Police officers were charged with acts intended to cause grievous harm, assault causing actual bodily harm, common assault, conspiracy to defeat justice and interference with witnesses. These officers were charged in relation to the Naqia Bridge case for assaulting and throwing a man off the bridge.

8 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm, acts intended to cause grievous harm, aiding and abetting assault causing actual bodily harm, aiding and abetting acts intended to cause grievous harm, common assault, giving false statements on oath, conspiracy to defeat justice and interference with witnesses. These officers were charged in relation to an assault case of suspects at Tavua Police station.

4 corrections officers were charged with the murder and assault causing actual bodily harm and common assault of a prisoner at Natabua Corrections Centre.

2 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm to two suspects in a drug case

The HRADC ‘s annual reports are also available on the Fiji Parliament website and specific cases investigated by the Commission are also widely publicised by the mainstream media. There is no secrecy about the manner in which allegations of torture and inhumane and degrading treatment are investigated and the outcomes of these investigations are made public.

While the report mentions NGOs and Red Cross, the State Department conveniently glosses over the fact that Visiting Justices and the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission have the powers and do visit places of detention.

Public Order Act and the power to detain suspected persons for up to 16 days

It is imperative to note that the amendments to the Public Order Act in 2017 was in response to the UN Security Council resolution which called on member states to strengthen their judicial, law enforcement and border control capacities and develop their capabilities to investigate the offence of terrorism and is in consonance with section 6(5) of the Fijian Constitution on the grounds of necessity.

The power to detain suspected persons for more than 48 hours and for a further 14 days is based on necessity. Section 17A (2), expressly provides that

“No person shall be detained under powers conferred by subsection (1) for a period exceeding 48 hours except with the authority of the Minister on whose directions such a person may be detained for a further period of 14 days if the Minister is satisfied that the necessary enquiries cannot be completed within 48 hours”.

Criticism of government as a crime of sedition and press freedom

The assertion that “the law includes criticism of government in its definition of the crime of sedition” is again incorrect.

Section 66 (a) (b) (c) and (d) of the Crimes Act very clearly stipulates that an act, speech or publication is not seditious when it is done with the intention of showing that Government has erred in any of its measures; pointing out errors or defects in the Government or the Constitution, or to persuade Fijians to change the law by lawful means.

It precludes criticism of Government and legitimate acts of dissent from the offence. These provisions are integral in preserving citizens ability to exercise democratic dissent. Nor does the assertion that “the media law authorizes the government to censor all news stories before broadcast or publication” hold any credence.

If this was the case then media organisations that are openly critical of government would have all shut down by now. In the face of claims of “self-censorship”, the mainstream media continues to publish robust criticism of authorities and giving platform to dissenting and divergent views.

The justifiable limitations placed on freedom of speech, expression and publication under section 17 of the Fijian Constitution are consistent with international human rights law in particular Article 19 and 20 (2) of the ICCPR.

While expressing alarm at the Media Industry Development Act, the report fails to show how many media organisations were prosecuted under the Act, for which transgressions and whether the Media Tribunal which is independent of the Authority and presided by a high court judge has convened at all.

Judiciary subjected to intimidation

The unsubstantiated claim that “the constitution provides for an independent judiciary, but the judiciary was subject to intimidation” is alarming and highly irresponsible and so is the claim that the “constitution and the law provide for a variety of restrictions on the jurisdictions of the courts” and warrants a prominent retraction if the State Department is unable to substantiate its use of the word “intimidation”.

Such generalisations, in my view, are an assault on judicial independence and impartiality. I draw the State Department’s attention to section 97 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) of the Fijian Constitution that guarantees judicial independence.

Furthermore, in relation to its observations on the jurisdictions of the court, I suggest the State Department also reads sections 98 (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) in relation to the Supreme Court, section 99 (3) in relation to the Court of Appeal and section 100 (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) with regard to the jurisdiction of the High Court and section 101 (2) with regard to the Magistrates Court of the Fijian Constitution.

The report fails to deconstruct the law to show how the purported restrictions on jurisdictions of the courts has effectively derailed the access and administration of justice. I find it equally curious that the State Department keeps making reference to “decrees” when “decrees” no longer exist.

Government human rights body, its independence and silence on politically sensitive human rights matters

The State Department erroneously refers to the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission as a “Government Human Rights Body”.

If the authors of the report could laboriously sift through the Fijian Constitution and adduce that the Constitution prohibits the Commission from investigating matters in relation to the 2006 coup and the abrogation of the 1997 Constitution, I fail to understand how they glossed over the fact that section 45 (7) of the Fijian constitution guarantees the independence of the institution from the state.

Nor did they make any effort to look at the powers of the Commission under section 12 of the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission Act. As documented in its Annual Reports and publicised by mainstream media, the Commission is able to independently dispense with its mandate including conducting investigations against the State.

This is evident in the various proceedings the Commission has instituted against the State. Alternative reports prepared by the Commission as well as submissions to parliamentary standing committees on existing and proposed laws attest to the Commission’s independence.

The Commission has expressed its views on a range of human rights issues that include: rights of arrested and detained persons, torture and brutality, use of force, on balancing the right to peaceful assembly against the imperatives of public order, on balancing rights and restrictions in the context of COVID-19 including curfews and lockdowns, discrimination on prohibited grounds, advocacy of hatred and the right to free speech, same sex marriage, sexual and gender based violence, human trafficking, business and human rights, rights of refugees and asylum seekers, rights of children and persons with disabilities, freedom of religion and the right to education, and most recently the deportation of the USP Vice-Chancellor.

There is no clarity as to what amounts to “politically sensitive’ human rights matters and what is deemed as typically taking government’s stance in public statements given that the Commission’s statements are premised on our domestic procedures and international human rights law.

How is speaking out against racism and communalism a pro-government agenda since it should be everyone’s concern? Why is the Commission’s call to strike a right balance between rights and restrictions whether it be about freedom of speech, expression and publication or freedom of assembly deliberately misconstrued as taking the side of government?

Contrary to the claims in the report, the Commission has been vociferous. Surely, if this report is premised on the observations of select media rather than a wide cross section of the mainstream media in Fiji, one would get an impression that the Commission is not independent.

Of course, the State Department does not acknowledge that it is not censorship but political bias that has plagued the possibility of accurate, balanced and fair reporting and this report is no exception.

Some examples of cases of torture and brutality investigated by the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission independently against the Fiji Police Force and Fiji Corrections Service

While the report impugns independent institutions like the judiciary and those responsible for the protection, promotion and preservation of human rights, there was neither any consultations with the state and independent institutions including the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission in the formulation of this report nor any ethic of constructive engagement over the years, as far as the HRADC is concerned, in relation to human rights in Fiji.

This does not mean that Fiji does not have any human rights challenges. We certainly do.

They include but by no means limited to sexual and gender based violence , torture and brutality at the hands of law enforcement agencies, rights of arrested and detained persons, racial and religious intolerance and hate speech, the need for constructive discussions on the right to peaceful assembly and the imperatives of public order and national security, the existential threat of climate change and the advent of COVID-19 and its attendant human rights challenges, and the need to ensure that the national human rights institution is compliant with the Paris Principles but Fiji continues to subject itself to scrutiny both domestically and at the highest human rights forums internationally, the most recent being the third cycle of its Universal Periodic Review at the Human Rights Council in Geneva.

Curiously the US State Department Report does not even make a cursory reference to Fiji’s UPR almost giving an impression that there is no accountability for human rights violations in Fiji, nor does it document our human rights achievements.

The US human rights record is hardly worthy of emulation but Fiji does not occupy an indomitable moral plateau with the compulsion to ritualistically produce a report on them every year. Given that the US jealously guards the right to free expression, or so it putatively claims, I will exercise mine and point out some of their human rights failings and the reason I raise these are because ironically some of these human rights failings form the basis of the report on Fiji.

This is a country that until recently had turned its back on the Paris Climate Agreement, had withdrawn from the UN Human Rights Council, placed sanctions against the International Criminal Court and has yet to ratify all core international human rights instruments.

These are Conventions on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, International Convention on the Protection, Convention on the Rights of the Child, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers, and Members of Their Families, International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

It has yet to establish an independent national human rights institution.

At the third cycle of its UPR, member states called on the USA to establish a moratorium on the death penalty, to put an end to life without parole sentence for juveniles, an end to arbitrary and indefinite detention, illegal and secret detention facilities, overcrowding in prisons, Police violence, use of excessive force and torture, racial profiling by law enforcement agencies, killing of civilians in military operations, gun violence, racism, extremism, xenophobia and hate speech directed at immigrants and asylum seekers, the adoption of punitive measures such as the incarceration of migrants and separation of migrant children from their parents to deter irregular entry and retrogressive policies that inhibit comprehensive and universal access to voluntary sexual and reproductive health services.

Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and immunity provisions in the Fijian Constitution

Just like the United States, Fiji is equally concerned with torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment and we have acknowledged this at home and internationally and the need for accountability without impunity for acts of egregious violations of human rights.

The claims about carte blanche immunity extended to security forces, however, is a distortion of the law and a complete misrepresentation of section 157 of the Fijian Constitution giving an impression that this provision is still being invoked in present day cases of torture and brutality to exonerate security forces.

While granting immunity to the President, the Prime Minister and Cabinet Ministers, Republic of Fiji Military Forces, Fiji Police Force, Fiji Corrections Service, Judiciary, public service and any public office from any criminal prosecution and from any civil or other liability in any court, tribunal or commission, in any proceeding including any legal, military, disciplinary or professional proceedings and from any order or judgement of any court, tribunal or commission, as a result of any direct or indirect participation, appointment or involvement in the Government from 5 December 2006 to the date of the first sitting of first Parliament elected after the commencement of this Constitution, section 157 of the Fijian Constitution expressly states “provided however any such immunity shall not apply to any act or omission that constitutes an offence under sections 133 to 146, 148 to 236, 288 to 351, 356 to 361, 364 to 374, and 377 to 386 of the Crimes Decree 2009”.

Absence of an independent oversight mechanism for the security forces

Quoting approvingly from a 2016 Amnesty International report, the State Department claims that “there is no independent oversight mechanism for the security forces”, “the legal framework means that no investigation can be initiated or disciplinary action taken against a Police officer without the consent or approval of the Police commissioner”, “authorized investigations were usually conducted by the Internal Affairs Unit, which reports to the Police commissioner, who decides the outcome of the complaint” and “information about the number of complaints, investigatory findings, and disciplinary action taken is not publicly available”.

This claim is misleading about the work of independent institutions such as the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission that independently investigates such matters and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions which sanctions charges.

Here are some examples of cases of torture and brutality investigated by the HRADC independently against the Fiji Police Force and Fiji Corrections Service (refer to table on page 5)

It is also imperative to note that information about the number of complaints, investigatory findings, and disciplinary action taken is available to the public.

The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions routinely releases statistics on serious crimes (sexual as well as non-sexual offences) on a monthly basis with cases and the outcome of the investigation resulting in charges.

This is available on their website and is also widely publicized by the mainstream media. Between 1 January to 31 December 2020, statistics from the ODPP show that a total of 20 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm in the course of arrest or in custody while 4 officers from the Fiji Corrections Services were charged with murder and assault.

The ODPP also in their release make available the nature of these offences.

Some of the examples include:

3 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm, acts intended to cause grievous harm to a 27-year-old man. Also charged with conspiracy to defeat justice and aiding and abetting. They allegedly assaulted a suspect with a concrete block and threw boiling water at him in the Police station.

2 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm to a 41-year-old man

5 Police officers were charged with acts intended to cause grievous harm, assault causing actual bodily harm, common assault, conspiracy to defeat justice and interference with witnesses. These officers were charged in relation to the Naqia Bridge case for assaulting and throwing a man off the bridge.

8 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm, acts intended to cause grievous harm, aiding and abetting assault causing actual bodily harm, aiding and abetting acts intended to cause grievous harm, common assault, giving false statements on oath, conspiracy to defeat justice and interference with witnesses. These officers were charged in relation to an assault case of suspects at Tavua Police station.

4 corrections officers were charged with the murder and assault causing actual bodily harm and common assault of a prisoner at Natabua Corrections Centre.

2 Police officers were charged with assault causing actual bodily harm to two suspects in a drug case

The HRADC ‘s annual reports are also available on the Fiji Parliament website and specific cases investigated by the Commission are also widely publicised by the mainstream media. There is no secrecy about the manner in which allegations of torture and inhumane and degrading treatment are investigated and the outcomes of these investigations are made public.

While the report mentions NGOs and Red Cross, the State Department conveniently glosses over the fact that Visiting Justices and the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission have the powers and do visit places of detention.

Public Order Act and the power to detain suspected persons for up to 16 days

It is imperative to note that the amendments to the Public Order Act in 2017 was in response to the UN Security Council resolution which called on member states to strengthen their judicial, law enforcement and border control capacities and develop their capabilities to investigate the offence of terrorism and is in consonance with section 6(5) of the Fijian Constitution on the grounds of necessity.

The power to detain suspected persons for more than 48 hours and for a further 14 days is based on necessity. Section 17A (2), expressly provides that

“No person shall be detained under powers conferred by subsection (1) for a period exceeding 48 hours except with the authority of the Minister on whose directions such a person may be detained for a further period of 14 days if the Minister is satisfied that the necessary enquiries cannot be completed within 48 hours”.

Criticism of government as a crime of sedition and press freedom

The assertion that “the law includes criticism of government in its definition of the crime of sedition” is again incorrect.

Section 66 (a) (b) (c) and (d) of the Crimes Act very clearly stipulates that an act, speech or publication is not seditious when it is done with the intention of showing that Government has erred in any of its measures; pointing out errors or defects in the Government or the Constitution, or to persuade Fijians to change the law by lawful means.

It precludes criticism of Government and legitimate acts of dissent from the offence. These provisions are integral in preserving citizens ability to exercise democratic dissent. Nor does the assertion that “the media law authorizes the government to censor all news stories before broadcast or publication” hold any credence.

If this was the case then media organisations that are openly critical of government would have all shut down by now. In the face of claims of “self-censorship”, the mainstream media continues to publish robust criticism of authorities and giving platform to dissenting and divergent views.

The justifiable limitations placed on freedom of speech, expression and publication under section 17 of the Fijian Constitution are consistent with international human rights law in particular Article 19 and 20 (2) of the ICCPR.

While expressing alarm at the Media Industry Development Act, the report fails to show how many media organisations were prosecuted under the Act, for which transgressions and whether the Media Tribunal which is independent of the Authority and presided by a high court judge has convened at all.

Judiciary subjected to intimidation

The unsubstantiated claim that “the constitution provides for an independent judiciary, but the judiciary was subject to intimidation” is alarming and highly irresponsible and so is the claim that the “constitution and the law provide for a variety of restrictions on the jurisdictions of the courts” and warrants a prominent retraction if the State Department is unable to substantiate its use of the word “intimidation”.

Such generalisations, in my view, are an assault on judicial independence and impartiality. I draw the State Department’s attention to section 97 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) of the Fijian Constitution that guarantees judicial independence.

Furthermore, in relation to its observations on the jurisdictions of the court, I suggest the State Department also reads sections 98 (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) in relation to the Supreme Court, section 99 (3) in relation to the Court of Appeal and section 100 (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) with regard to the jurisdiction of the High Court and section 101 (2) with regard to the Magistrates Court of the Fijian Constitution.

The report fails to deconstruct the law to show how the purported restrictions on jurisdictions of the courts has effectively derailed the access and administration of justice. I find it equally curious that the State Department keeps making reference to “decrees” when “decrees” no longer exist.

Government human rights body, its independence and silence on politically sensitive human rights matters

The State Department erroneously refers to the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission as a “Government Human Rights Body”.

If the authors of the report could laboriously sift through the Fijian Constitution and adduce that the Constitution prohibits the Commission from investigating matters in relation to the 2006 coup and the abrogation of the 1997 Constitution, I fail to understand how they glossed over the fact that section 45 (7) of the Fijian constitution guarantees the independence of the institution from the state.

Nor did they make any effort to look at the powers of the Commission under section 12 of the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission Act. As documented in its Annual Reports and publicised by mainstream media, the Commission is able to independently dispense with its mandate including conducting investigations against the State.

This is evident in the various proceedings the Commission has instituted against the State. Alternative reports prepared by the Commission as well as submissions to parliamentary standing committees on existing and proposed laws attest to the Commission’s independence.

The Commission has expressed its views on a range of human rights issues that include: rights of arrested and detained persons, torture and brutality, use of force, on balancing the right to peaceful assembly against the imperatives of public order, on balancing rights and restrictions in the context of COVID-19 including curfews and lockdowns, discrimination on prohibited grounds, advocacy of hatred and the right to free speech, same sex marriage, sexual and gender based violence, human trafficking, business and human rights, rights of refugees and asylum seekers, rights of children and persons with disabilities, freedom of religion and the right to education, and most recently the deportation of the USP Vice-Chancellor.

There is no clarity as to what amounts to “politically sensitive’ human rights matters and what is deemed as typically taking government’s stance in public statements given that the Commission’s statements are premised on our domestic procedures and international human rights law.

How is speaking out against racism and communalism a pro-government agenda since it should be everyone’s concern? Why is the Commission’s call to strike a right balance between rights and restrictions whether it be about freedom of speech, expression and publication or freedom of assembly deliberately misconstrued as taking the side of government?

Contrary to the claims in the report, the Commission has been vociferous. Surely, if this report is premised on the observations of select media rather than a wide cross section of the mainstream media in Fiji, one would get an impression that the Commission is not independent.

Of course, the State Department does not acknowledge that it is not censorship but political bias that has plagued the possibility of accurate, balanced and fair reporting and this report is no exception.

Some examples of cases of torture and brutality investigated by the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission independently against the Fiji Police Force and Fiji Corrections Service