By Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi The apparent absence of debate, particularly among the Taukei, is attributed by commentators to ‘a culture of silence’. Open, vigorous public discourse is not yet a feature of Taukei or Fijian society at large. It has been explained in terms of a cultural milieu in which authority and communal structures coalesce to muffle expression. While media controls and self-censorship have not helped, it is the epistemology, ways of thinking, of the Taukei that invites closer scrutiny. ‘Silence’ does not necessarily mean consent. It is the lack of oral and written expression about issues passing for acquiescence. From the colonial era to the present, Taukei took refuge in silence until the political climate improved. Social media (Facebook, Twitter, blog sites etc.) represent a contemporary variation, allowing disaffected Taukei to express opinions anonymously. An assertive few, on opposing sides of the divide, eschew such inhibitions in that virtual world. Safe haven notwithstanding, it is outside the wider public domain. Sanctuary afforded by ‘silence’ comes at a price: uncontested interpretations of issues and events become historical truth and received wisdom. Reluctance persists among Taukei to ventilate issues of interest openly whether the traditional system, sustaining Taukei culture, the Taukei language, qoliqoli, the protection of land or the status of indigenous people post-December 2006. It is compounded by several factors. Blood and kinship ties remain significant. Personalities matter more than issues. Opinions are an extension of the person and difficult to separate. And the ubiquity of connections renders security in numbers of larger societies meaningless. Consequently, leaders take offence easily because there is no distance between them and their audience. The ‘personal’ element permeates and colours all relationships: traditional, political, economic, social and religious. Social interaction is complicated by the relative frequency with which people meet at weddings, funeral gatherings, other ‘oga’ (traditional/social obligations) and settings. The implications for free-flowing discourse are obvious: reluctance to disagree for fear of offending. Communal thinking is interwoven with this ‘connectedness’. The group is preeminent and the individual secondary. The latter is a component of the whole. His/her utility lies in the credibility and weight lent to the consensus. It is sometimes self-evident, but more often a combination of interventions from key persons or groups and circumstances. There is little leeway for the self-validation essential for the flow of ideas. Seniority determines one’s right of audience and “who can and cannot speak”. Empowerment constitutes work in progress particularly for women and youth. Advocating a public position necessitates taking a stand. It is not as simple as Nike’s ‘Just do it’ slogan. Consequences arise: it obliges others to react. This may be unsettling if they prefer not to be involved. Individuals or groups are identified with a position, limiting their room for manoeuvre with possible repercussions. In June 1977, as naïve law students, my good friend Graham Leung and I wrote to the Fiji Times criticising then Governor-General Ratu Sir George Cakobau’s decision not to invite Mr S. M. Koya to form government. The National Federation Party had won a plurality in the May election. My fleeting temerity was swiftly aborted by the opprobrium my politician mother endured. Dissembling is a valued cultural trait: maintenance of relationships and social cohesion is the highest good. Consensus is valued and dissent discouraged. Where it arises or is anticipated, the preceding discussion and ensuing outcome are framed in general terms. It allows those present to project a ‘consensus’, interpreting proceedings to their benefit. Individuals usually reserve judgment during this process to gauge the tide of debate. Throughout this exercise, details are glossed over and face is saved. Either way, it does not allow for closely argued exchanges characteristic of intellectuals and academia. There is also a sense that indigenous identity is a Taukei prerogative. While not a view I share, the assumption is only Taukei can appreciate the essence of indigeneity. Disinclination to participate in public fora is the result. Interestingly, the extent to which Taukei are committed to “a common and equal citizenry” of the present dispensation is intriguing. Ambivalence in acknowledging this country belongs to all Fijians continues. Fuelled by a perception that shared identity has been unmatched by reciprocal gestures, for example as in recognising the autochthonous and unique character of the Taukei language. A simple illustration: Taukei wince at references to the Taukei rather than Fijian language, bespeaking inferiority. Furthermore, use of the phrase “iTaukei” in English displays egregious unfamiliarity with the Taukei language itself (legislative fiat aside – The ‘i Taukei’ reference is mandated by Fijian Affairs (Amendment) Decree No 31 of 2010). ‘I’ partially serves as the article as in ‘Na i Taukei’ (the Taukei) or ‘Na i Vola Tabu’ (the Holy Bible). The phrase ‘the iTaukei’ in English (lit. ‘the the Taukei’) sounds repetitive, awkward and pretentious to Taukei ears, especially when uttered by non-Taukei. These minor irritants nevertheless demonstrate how the ‘culture’ curtails more honest dialogue. Taukei keep these feelings to themselves, stoking victimhood. Shared, it serves to heighten awareness and sensitivity among Fijians although that process may be confronting. Those observations about use of ‘i Taukei’ exemplify the spectacle of unchallenged perspectives morphing into accepted orthodoxy. Wadan Narsey has expressed concern about this trait in analysing possible causes for the ‘hibernation’ (Narsey’s description) of ‘Fijian’ (i.e. Taukei) intellectuals. The manner in which Taukei relate to authority bears on this discourse. The hierarchy of the traditional system, although modified, continues to apply between leaders and led today. Forthright, direct comment yields to endorsing the prevailing orthodoxy. It safeguards the position of followers in terms of anticipated largesse, guising their actual opinions. Taukei are accustomed to dealing with their rulers in this way as a means of self-preservation. The extensive protestations of support for the government, some of which is doubtless genuine, may be understood in that light. At the same time, some perspective is useful. While the culture has tended to reinforce the status quo by limiting challenges to authority, individuals capable of strong leadership have been able to buck the system to attract a following. Navosavakadua, Apolosi R Nawai, Ratu Emosi of Daku, Sairusi Nabogibogi and Ravuama Vunivalu formerly, Butadroka, Ratu Osea Gavidi, Bavadra, Rabuka, George Speight and Bainimarama more recently have lain claims to prominence. Their populist appeal and charisma, the promise of a better future and a pointed rebuke to the ‘establishment’ for supposed failings partly account for their success (though varied). Levelling of both the Taukei community and wider society, particularly since independence, reflects an irreversible trend: those from more representative backgrounds dominating leadership. That dynamic will have a liberalising effect over time. A vision of the future surfaced during debate in 2006 over the Qoliqoli Bill which sought to extend property rights to Taukei fishing rights. It was protracted, vigorous even fierce but open and peaceful. Such scenarios are attainable but an enabling environment is a prerequisite. The other relevant consideration is that informed and sustained debate requires familiarity with issues, intellectual inquiry and reflection. For Taukei, earning a living, raising a family, undertaking tertiary studies and involvement with ‘oga’ consume their time, energies and resources. It is one reason Taukei are often absent from activities such as service clubs. ‘Service’ as they conceive it is material and financial support provided to immediate and extended family; or bearing the educational and boarding expense of close kin in straitened situations. Taken with obligations to the vanua and the lotu, there is a cost: capacities for conceptualising and articulation thereof are appreciably diminished. Additionally, the phenomenon of reading not being popular among the Taukei and wider population is worrisome. It is more than a means for acquiring credentials. Exposure to ideas, development of rational thought and nurturing of imagination engendered by this process is critical. Reading moulds the shape, quality and frequency of debate. It stimulates the ability to formulate, synthesise and articulate ideas clearly and logically. |

REBUKED: "In June 1977, as naïve law students, my good friend Graham Leung and I wrote to the Fiji Times criticising then Governor-General Ratu Sir George Cakobau’s decision not to invite Mr S. M. Koya to form government. The National Federation Party had won a plurality in the May election. My fleeting temerity was swiftly aborted by the opprobrium my politician mother endured." - Madraiwiwi

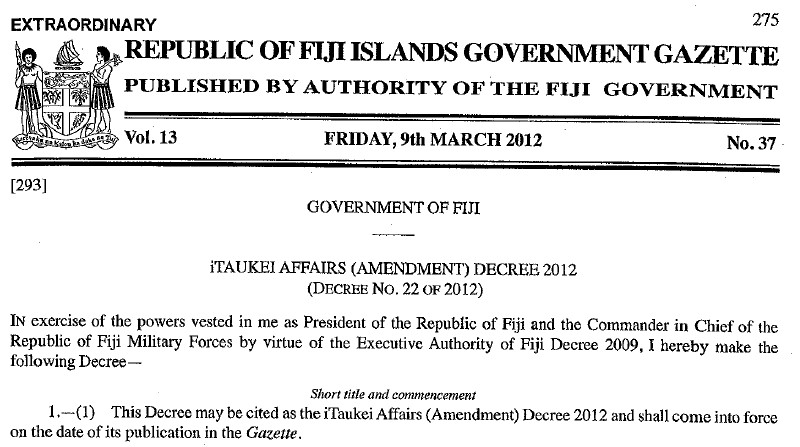

"Taukei wince at references to the Taukei rather than Fijian language, bespeaking inferiority. Furthermore, use of the phrase “iTaukei” in English displays egregious unfamiliarity with the Taukei language itself (legislative fiat aside – The ‘i Taukei’ reference is mandated by Fijian Affairs (Amendment) Decree No 31 of 2010). ‘I’ partially serves as the article as in ‘Na i Taukei’ (the Taukei) or ‘Na i Vola Tabu’ (the Holy Bible). The phrase ‘the iTaukei’ in English (lit. ‘the the Taukei’) sounds repetitive, awkward and pretentious to Taukei ears, especially when uttered by non-Taukei."

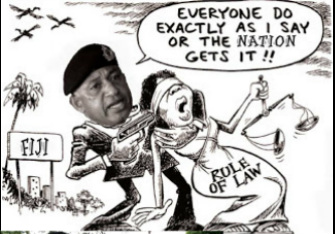

"The manner in which Taukei relate to authority bears on this discourse. The hierarchy of the traditional system, although modified, continues to apply between leaders and led today. Forthright, direct comment yields to endorsing the prevailing orthodoxy. It safeguards the position of followers in terms of anticipated largesse, guising their actual opinions. "

"Taukei are accustomed to dealing with their rulers as a means of self-preservation. The extensive protestations of support for the government, some of which is doubtless genuine, may be understood in that light."Despite that lack, the situation is changing gradually. Regulation is being eased accompanied by empowerment initiatives for women, youth, people with disabilities, rural populations and other marginalised groups. Rising standards of education and exposure especially in the form of foreign work experience, the present dispensation, the pervasive presence of the media, in addition to accessibility to information technology have all had an impact. The resulting paradox: a more permissive social environment facilitating increasingly diverse opinion. There remains a need to provide more open, honest debate within Taukei and wider Fijian society, so citizens are able to participate effectively in the issues of the day. It is critical for our development as a nation and as part of the global village. For this to happen, understanding this psyche of ‘silence’ makes possible remedial measures through socialisation, educational initiatives, empowerment, community and civil society support and other means. While ensuring the emerging landscape is focused and engaging rather than visceral; promoting balance with respect but not hostage to sectarian sensibilities. Journeying beyond a culture of silence to where meaningful dialogue and debate become commonplace. Source:http://republikamagazine.com/2014/03/beyond-a-culture-of-silence/ |

|

8 Comments

What culture of silence?

19/3/2014 11:06:22 pm

where was the native Fijians ” culture of silence” when they were bused in to protest on the streets to destabilise the Bavadra Government in 1987? if my memory serves me correctly they were loud and boisterous and aggressive and threatening.

Reply

silence please

20/3/2014 02:25:30 am

Of course.... and then you miss the point. Again.

Reply

ratu

20/3/2014 10:23:33 pm

Army not on fijian side.khaiyum army guards.isarel was punished seems fijian been punished too .time fijians and indians united in prayers to forgive each other and get ready to punish khaiyum fijian army.

Reply

Fijileaks Editor

20/3/2014 01:39:55 am

Dear Commentators

Reply

Fijileaks Editor

20/3/2014 03:22:33 am

Lamusona Levu

Reply

Concerned with Passion

20/3/2014 01:46:36 pm

I agree some perspective is useful that culture has tended to reinforce the status quo by limiting challenges to authority, individuals capable of strong leadership have been able to buck the system to attract a following.

Reply

The real USP VC

20/3/2014 10:40:02 pm

Aiyaz Sayed Khaiyum is calling the shots at USP. VC Rajesh Chandra is Aiyaz's boy. So is Ashwin Raj.

Reply

22/3/2014 09:27:59 pm

You are wrong. The real vc at USP is Rajesh Chandra's wife. She has for a long time been the decision maker on who should be fired or promoted at USP. That dumb woman was a terrible teacher, arrogant and acted like a smarty pants. She couldn't write anything without errors. No wonder she was never promoted. What she did and does is threaten staff who say or are friends with those who criticize Rajesh. All who are around Rjesh are those who she likes.Wonder what she makes of the friendship between Anjela and Rajesh.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

[email protected]ARCHIVES

September 2020 August 2020 July 2020 June 2020 December 2018 November 2018 October 2018 January 2018 December 2017 November 2017 October 2017 September 2017 August 2017 July 2017 June 2017 May 2017 April 2017 March 2017 February 2017 January 2017 December 2016 November 2016 October 2016 September 2016 August 2016 July 2016 June 2016 May 2016 April 2016 March 2016 February 2016 January 2016 December 2015 November 2015 October 2015 September 2015 August 2015 July 2015 June 2015 May 2015 April 2015 March 2015 February 2015 January 2015 December 2014 November 2014 October 2014 September 2014 August 2014 July 2014 June 2014 May 2014 April 2014 March 2014 February 2014 January 2014 December 2013 November 2013 October 2013 September 2013 August 2013 July 2013 June 2013 May 2013 April 2013 March 2013 February 2013 January 2013 December 2012 October 2012 September 2012 |