COMING SOON:

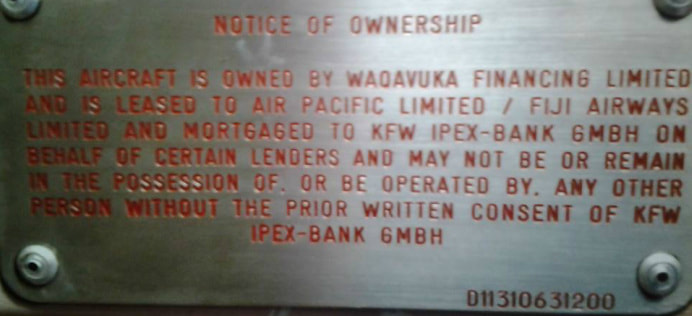

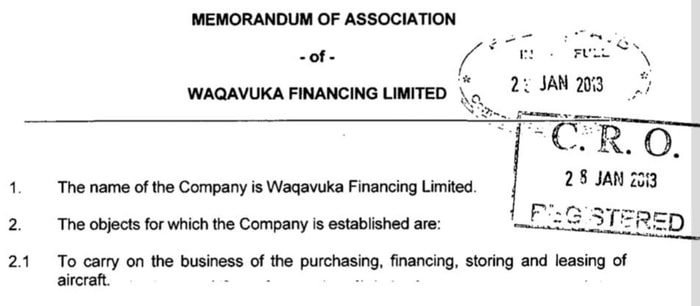

The Inside Story on Waqavuka Financial Limited

Seven years ago, in 2013, our Founding Editor-in-Chief spoiled the celebrations when he revealed that the new Airbus A330 aircraft was not owned by Fiji Airways but by Waqavuka. For the next seven years, it never fell off our radar, and we have finally tracked its 'flight path' from Fiji to Ireland, and will be revealing all about Waqavuka on Fijileaks. Remember, Aiyaz Khaiyum's holy sing sheet Fiji Sun scrambling onboard after our disclosure about Waqavuka, and has not stopped portraying us as anti-Government blogsite, while not asking 'Kader Khan' searching questions. However, the paper keeps reproducing the Waqavuka ownership plague we first revealed in 2013. While releasing selected details from the 2019 Fiji Airways Annual Report, Khaiyum claimed Waqavuka Financing is 'public knowledge'. If so, why is he hiding in the Fiji Airways 'cargohold' with his Annual Report. How much is Waqavuka being paid to act as "third party" between the banks and Fiji Airways?

Meanwhile, the saga of Air Mauritius and RavnAir in the age of COVID 19

Air Mauritius is currently under voluntary administration. Amidst the Covid-19 crisis, the Mauritian national carrier wishes to give itself the necessary breathing space and set the conducive conditions for restructuring opportunities in order to stay afloat. It has not filed for bankruptcy. The Bankruptcy Division of the Supreme Court of Mauritius has granted the Administrators until 30 November 2020 to convene a meeting and it is scheduled to be held within seven days of that date. There is uncertainty as to when international air traffic will resume and all indications tend to show that normal activities will not pick up until late 2020. In these circumstances, it is expected that Air Mauritius will not be able to meet its financial obligations in the foreseeable future. The Board, therefore, took the decision to place the Company under voluntary administration in order to safeguard the interest of the Company and that of all its stakeholders. But what led Air Mauritius entering administration? RUBEINA SAWDOO has filed the following report from MAURITIUS:

Rubeina Sawdoo

Rubeina Sawdoo The news of Air Mauritius being placed into administration dropped like a bomb two days ago. (28 April 2020). Though the eventual collapse of the airline can easily be blamed on the COVID-19 crisis, as it had been stated, Air Mauritius has been facing financial troubles way before the coronavirus outbreak. With all its international and domestic flights grounded till 15th May due to the pandemic, the already struggling airline had no alternative but to enter voluntary administration. Unfortunately, the coronavirus crisis led to the complete erosion of the company’s revenues, according to the board of directors of Air Mauritius.

Unprecedented crisis

In January 2020, Air Mauritius management had set up a Transformation Steering Committee to address the financial difficulties of the business model. Though the company claimed progress was made, the inevitable decline continued. Air Mauritius has monthly fixed costs of over $20m/Rs800m MUR, which includes the salaries of around 3,000 employees and the leasing costs of Airbus A350-900 and A330-900neo. The uncertainty about when international traffic will resume only resulted in voluntary administration of Air Mauritius so that the company can buy some time to restructure.

Fight for survival for years

Just last year, Air Mauritius had incurred losses of $25m/Rs998.2m MUR. Previous years were not any better, with meager profits or even more significant losses. It was clear that the company had trouble making money. Surprisingly, even during the high season in Mauritius (October to December), losses have accumulated while travel and tourism operators make the most profits during the same period. Increasing competition and rising costs of fuels were pointed out as reasons for the company’s low profits. Even at the beginning of 2019, Air Mauritius already expected the 4th quarter of the year to be challenging. Experts were asking for a business model to get the company back on track; nothing much was done. Significant changes would include general operations and staffing to be able to trim down losses.

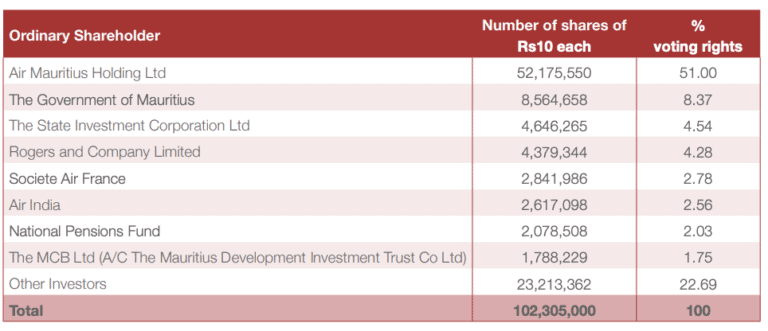

Bad management

Air Mauritius has been very badly managed since the early 2000s. (Fijileaks: Viljoen, who took up his position with Fiji Airways in October 2015, was CEO of Air Mauritius since 2010). Even if frequent changes have been seen at top-level management in recent years, the company’s board has remained intact, and the government has remained the majority shareholder (42.5%). Most key strategic decisions, plans and business models are approved by the company’s board, which is too widely backed by politics. For the past 20 years or so, no government has been able to strike the right balance in the company with its role as shareholder. With various airlines like Etihad or Qatar Airways approaching Air Mauritius to offer help, Air Mauritius chose Emirates for interline agreements. This was not considered to be the best decision. Some argue that Air Mauritius should have followed Air Seychelles’ move to partner with Etihad. This partnership has proved fruitful for the airline and did not stop Air Seychelles from taking delivery of its new Airbus A320neo despite the current crisis

Possible solutions

Various experts from Mauritius have come forward to offer possible solutions while Air Mauritius is in administration. While it is not a time to play the blame game, many are blaming the government of Mauritius for not acting. While the government is helping hundreds of companies on the island to avoid a rise in unemployment, its inaction towards Air Mauritius will lead to inevitable job losses.

According to Rama Sithanen, the ex-finance minister of Mauritius, Air Mauritius is the most affected company during the coronavirus crisis. He proposed the following solutions:

Unprecedented crisis

In January 2020, Air Mauritius management had set up a Transformation Steering Committee to address the financial difficulties of the business model. Though the company claimed progress was made, the inevitable decline continued. Air Mauritius has monthly fixed costs of over $20m/Rs800m MUR, which includes the salaries of around 3,000 employees and the leasing costs of Airbus A350-900 and A330-900neo. The uncertainty about when international traffic will resume only resulted in voluntary administration of Air Mauritius so that the company can buy some time to restructure.

Fight for survival for years

Just last year, Air Mauritius had incurred losses of $25m/Rs998.2m MUR. Previous years were not any better, with meager profits or even more significant losses. It was clear that the company had trouble making money. Surprisingly, even during the high season in Mauritius (October to December), losses have accumulated while travel and tourism operators make the most profits during the same period. Increasing competition and rising costs of fuels were pointed out as reasons for the company’s low profits. Even at the beginning of 2019, Air Mauritius already expected the 4th quarter of the year to be challenging. Experts were asking for a business model to get the company back on track; nothing much was done. Significant changes would include general operations and staffing to be able to trim down losses.

Bad management

Air Mauritius has been very badly managed since the early 2000s. (Fijileaks: Viljoen, who took up his position with Fiji Airways in October 2015, was CEO of Air Mauritius since 2010). Even if frequent changes have been seen at top-level management in recent years, the company’s board has remained intact, and the government has remained the majority shareholder (42.5%). Most key strategic decisions, plans and business models are approved by the company’s board, which is too widely backed by politics. For the past 20 years or so, no government has been able to strike the right balance in the company with its role as shareholder. With various airlines like Etihad or Qatar Airways approaching Air Mauritius to offer help, Air Mauritius chose Emirates for interline agreements. This was not considered to be the best decision. Some argue that Air Mauritius should have followed Air Seychelles’ move to partner with Etihad. This partnership has proved fruitful for the airline and did not stop Air Seychelles from taking delivery of its new Airbus A320neo despite the current crisis

Possible solutions

Various experts from Mauritius have come forward to offer possible solutions while Air Mauritius is in administration. While it is not a time to play the blame game, many are blaming the government of Mauritius for not acting. While the government is helping hundreds of companies on the island to avoid a rise in unemployment, its inaction towards Air Mauritius will lead to inevitable job losses.

According to Rama Sithanen, the ex-finance minister of Mauritius, Air Mauritius is the most affected company during the coronavirus crisis. He proposed the following solutions:

- A new structure for the company.

- Capitalizing with the current shareholders.

- Selling the company. Which he says will be done cheaply and not the best solution.

- Demerge to avoid subsidiary companies of Air Mauritius to be affected..

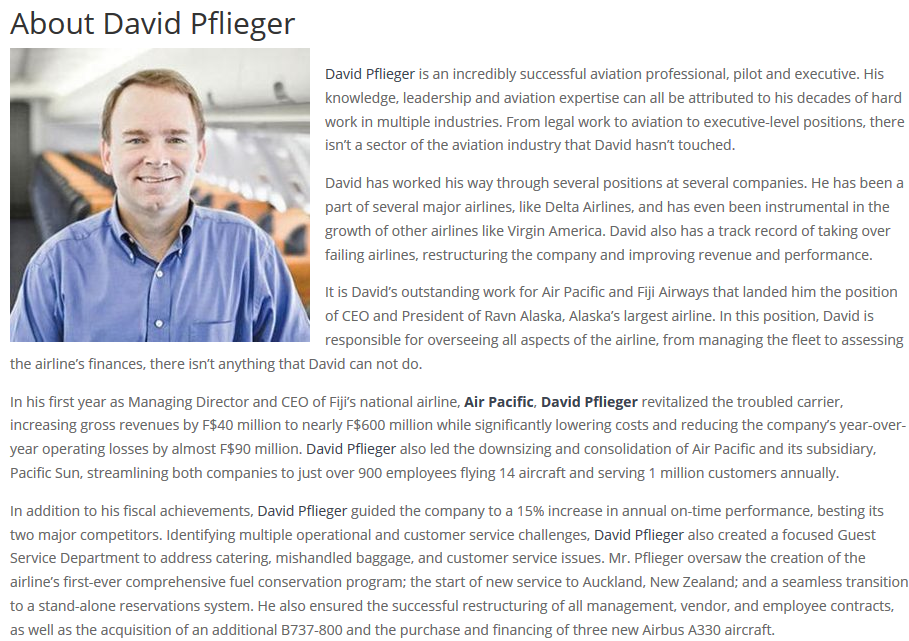

RAVN was $US90million in Debt at the time of its recent bankruptcy, and David Pflieger, the former Fiji Airways CEO, oversaw Ravn's final collapse. "Alaska’s largest regional air carrier will be liquidated unless it can receive more federal coronavirus loans", screamed Alaska newspapers. RavnAir announced in early April that it was laying off all staff, ceasing all operations and filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protections due to coronavirus-related losses. Dave Pflieger, the CEO of RavnAir, sent an email, explaining that the air carrier needed to secure loans from a Advertisement federal coronavirus package to survive a 90% drop in passenger bookings. In the end, he couldn't save RavnAir's fate. |

Ravn had applied from the US Federal Government for a $75 million the 'pandemic loan' and was told it would be eligible for about $5.2 million, Chief Executive Dave Pflieger told The Wall Street Journal

The collapse of Ravn: How Alaska’s biggest rural air carrier met its end

By Colleen Mondor, Anchorage Daily News, April 2020

She is the author of The Map of My Dead Pilots: The Dangerous Game of Flying in Alaska

As Ravn Air Group points to the coronavirus as the source of the company’s bankruptcy, it is necessary to take a step back and consider Ravn’s situation before the onset of COVID-19. The largest air carrier operation in the state almost entirely owes its success to a 2002 change in the bypass mail rules which initiated an era of mergers, expansions and accidents that are unprecedented in Alaska aviation history. The fact that the U.S. Postal Service is now forced to rely on smaller air carriers to deliver the mail is an irony that is likely not lost on the many people who lost their jobs years ago when Ravn began its rise from the ashes of their employers.

Ravn Air Group is composed of multiple aviation companies obtained via merger, asset acquisition and outright purchase. It includes the operating certificates of Corvus Airlines (formerly Era Aviation), Hageland Aviation and PenAir. There is also Frontier Flying Service, its founding member, whose air carrier certificates (both Part 121 and Part 135) are dormant. In terms of equipment, routes and structures, Ravn also contains what was formerly Cape Smythe Air Service, most of Arctic Circle Air Transportation and Yute Air. And all of this economic activity began with the Rural Services Improvement Act (RSIA).

Under Sen. Ted Stevens’s guidance, RSIA became law in 2002 as an effort to both lower USPS costs and provide immediate support to passenger aircraft business to the Bush. It was pointedly designed to offer a larger portion of the revenue-rich bypass mail to air carriers operating under Part 121 of the Federal Aviation Regulations (those flying aircraft with 10 or more seats). The bypass split was divided more heavily to passenger carriers (75% vs. 25% to all cargo), and within that passenger cut, the Part 121 operators received preference. (All passenger-carrying aircraft had to carry at least 20% of a destination’s total passenger traffic to receive bypass.)

Without getting too deep into the many nuances of the law, RSIA ensured that although Part 121s were paid at a lower rate (saving the USPS money), they received more bypass, which gave them an essentially guaranteed revenue stream. The goal was to see more passenger traffic in larger aircraft (which were deemed safer due to Part 121‘s more stringent regulations) carrying bypass to the Bush. Cargo companies received a much smaller split with the goal that most of them would leave the bypass market. (Main-haul carriers serving hub destinations also had rule changes.)

RSIA also contained what came to be termed the “121 hammer." If a Part 121 passenger operator entered a market, the companies in that market flying smaller aircraft under Part 135 of the regulations were placed on a clock to obtain a Part 121 certificate by 2008 or lose the mail. The costs to fly Part 121 are substantial, and a company incurs millions of dollars in expenses for aircraft acquisition, flight training, maintenance and management personnel before seeing any profit. The Part 121 certification process also takes years to complete. There were only three passenger Part 121 companies in the Bush at the time RSIA passed: Era Aviation, PenAir and Frontier Flying Service.

Within a few years of the bill’s passage, several Part 135 companies either went out of business or dropped out of scheduled service. As the competitive landscape cleared, Frontier purchased the assets for Cape Smythe Air Service in 2005, which included its North Slope routes, thus initiating an era of nearly nonstop expansion for the Fairbanks-based company. Then another bypass change was announced.

In December 2006, a revision to RSIA was passed which gave Part 121 carriers immediate access to bypass for new bush destinations for a full year regardless of whether they carried any passengers at all. While flying in the face of RSIA’s professed preference for supplementing passenger service, this revision provided an immediate economic advantage to Part 121 operations over their Part 135 competition. Further, the revision allowed the first three Part 121 operators who entered a route to receive a split of an extra 10% of the bypass for that route by reducing the Part 135 and cargo shares. Although the “121 hammer” was removed, with no explanation or compensation to those companies, such as Warbelow’s Air Ventures, that had invested millions into pursuing 121 certification, the damage was done. The USPS had reshaped the aviation industry in Alaska to the direct benefit of the three companies that became part of Ravn Air Group.

In 2008, Frontier and Hageland Aviation merged (branding as “Frontier Alaska”), and one year later, the new company purchased Era Aviation, rebranding then as Era Alaska. (The Ravn Air Group brand arrived in 2014). The Era deal was touted in the Alaska Journal of Commerce as likely bringing the new entity 24 million pounds of mail annually plus revenues of $100 million. Even before the 2018 purchase of PenAir in bankruptcy court, Ravn would cover nearly every corner of Alaska and in many places, as is now apparent, they were enabled to become the only air travel option in town.

In 2015, two of Ravn’s three owners (Jim Tweto and Mike Hageland) were bought out after its CEO, Bob Hajdukovich, secured financing from investor JF Lehman and Co. Lehman then received a majority stake in the company. (A second private equity firm, W. Capital Partners, received a stake as well with the Hajdukovich family retaining a minority percentage.) At the time, former U.S. Sen. Mark Begich, made a prophetic comment on the deal, telling the ADN, "From an aviation standpoint, recapitalization is good news. But the real question here is, what’s their objective? Is it sustainable and long-term?”

Five years later, we have an answer.

Through changes in ownership and management, as federal inspectors cycled in and out, and chief pilots, directors of operation, safety inspectors and directors of maintenance were fired, resigned or replaced, one darker consistency in Ravn’s business practice became pervasive — a relentless litany of accidents. Historically, before Ravn existed, its bush carrier, Hageland Aviation, was in trouble. In the 1990s, Hageland crashed 18 times, and in the 2000s, before the initial merger with Frontier, it crashed 11 more times. Altogether, between 1990 and its most recent accident in January of this year, Hageland Aviation has crashed 43 times, resulting in 29 fatalities and 28 injuries.

Along with the other Ravn carriers, Frontier, Corvus and PenAir, the air group has been in 20 accidents since 2008 — including, most dramatically, last October’s crash in Dutch Harbor which resulted in only the second Part 121 fatality in the entire U.S. during the past decade.

In that same period, Bering Air has been in four accidents, Alaska Central Express has been in four, Alaska Seaplanes has been in three and Warbelow’s Air Ventures has been in one.

In the wake of Hageland’s multiple-fatality accident in St. Marys in 2013, the Federal Aviation Administration revealed numerous shortcomings within the company’s management structure, including an a poor overall safety culture. It was revealed in that investigation that FAA officials had prepared a case to revoke Hageland’s operating certificate, but it was not pursued by their legal arm. FAA personnel also disclosed the $200,000 fund Hageland’s maintained to pay enforcement-related fines.

After the multiple-fatality crash in Togiak in 2016 the FAA discussed with investigators its revised efforts to work with Hageland (and thus Ravn) under a new enforcement method termed “compliance philosophy." This strategy was based on the concept that enforcement only worked on those companies that could not or would not comply. Compliance philosophy, according to the FAA, recognized that companies made inadvertent mistakes. The day the National Transportation Safety Board released the Togiak report — which detailed failures in the cockpit, the company and with FAA oversight — Hageland crashed again.

Following the Dutch Harbor accident, Ravn lost its Capacity Passenger Agreement with Alaska Airlines, which resulted in a sharp reduction in service to the village of Unalaska. The company’s Part 121 on-time performance has struggled over the past several years, and its reputation has suffered from a habit of same-day cancellations. The coronavirus might have been the last straw but, compared with its costly accident record and other concerns, it is not the only factor and in considering all that came before it, the virus likely was not even the most cumulatively destructive.

The long history of Ravn Air Group includes, at its center, four individual operating certificates. Collectively, these companies encompass a huge swath of Alaska’s history and have touched countless lives. In the past decade, they have moved thousands of tons of mail and flown hundreds of thousands of passengers. And yet, on every level that matters, Ravn is proof that the RSIA experiment and FAA oversight have collectively failed Alaskans. While it may have saved the USPS money, the advantages RSIA afforded to Part 121 air carriers directly translated into Ravn’s increased revenues and fueled its ambitious expansion, allowing the company to transform Hageland Aviation into the largest scheduled Part 135 commuter in the U.S. But Ravn’s safety record is nothing less than catastrophic, and despite its dominant industry position it has failed to weather an economic storm that its competitors continue to prudently navigate.

Over the years, Ravn and its cohorts have placed the blame for its crashes on Alaska’s weather, infrastructure and “bush pilot culture." More than once, the company has redirected accountability toward its pilots, maintenance personnel and, in the case of PenAir Flight 3296, the aircraft itself. Unfortunately, Ravn’s many management figures have never attained the level of self-awareness that might have spared its employees the economic devastation of the past few weeks. But one thing is clear: in its determination to increase Part 121 passenger operations, RSIA ushered in the destruction of all of the regional Part 121 passenger carriers in Alaska. Further, through foundational neglect, the FAA now possesses a legacy of injury and death in the state that will reverberate for years.

After all the broken promises and tragedies, it will now be up to those RSIA snubbed so long ago to pick up the pieces and keep the mail moving. And as those Part 135 operators scramble to fill the enormous gaps left by this abrupt bankruptcy, all Alaskans should consider that although the Ravn Air Group story does not begin with the coronavirus, perhaps it is time to accept that this is where it ends.

Ravn Air Group is composed of multiple aviation companies obtained via merger, asset acquisition and outright purchase. It includes the operating certificates of Corvus Airlines (formerly Era Aviation), Hageland Aviation and PenAir. There is also Frontier Flying Service, its founding member, whose air carrier certificates (both Part 121 and Part 135) are dormant. In terms of equipment, routes and structures, Ravn also contains what was formerly Cape Smythe Air Service, most of Arctic Circle Air Transportation and Yute Air. And all of this economic activity began with the Rural Services Improvement Act (RSIA).

Under Sen. Ted Stevens’s guidance, RSIA became law in 2002 as an effort to both lower USPS costs and provide immediate support to passenger aircraft business to the Bush. It was pointedly designed to offer a larger portion of the revenue-rich bypass mail to air carriers operating under Part 121 of the Federal Aviation Regulations (those flying aircraft with 10 or more seats). The bypass split was divided more heavily to passenger carriers (75% vs. 25% to all cargo), and within that passenger cut, the Part 121 operators received preference. (All passenger-carrying aircraft had to carry at least 20% of a destination’s total passenger traffic to receive bypass.)

Without getting too deep into the many nuances of the law, RSIA ensured that although Part 121s were paid at a lower rate (saving the USPS money), they received more bypass, which gave them an essentially guaranteed revenue stream. The goal was to see more passenger traffic in larger aircraft (which were deemed safer due to Part 121‘s more stringent regulations) carrying bypass to the Bush. Cargo companies received a much smaller split with the goal that most of them would leave the bypass market. (Main-haul carriers serving hub destinations also had rule changes.)

RSIA also contained what came to be termed the “121 hammer." If a Part 121 passenger operator entered a market, the companies in that market flying smaller aircraft under Part 135 of the regulations were placed on a clock to obtain a Part 121 certificate by 2008 or lose the mail. The costs to fly Part 121 are substantial, and a company incurs millions of dollars in expenses for aircraft acquisition, flight training, maintenance and management personnel before seeing any profit. The Part 121 certification process also takes years to complete. There were only three passenger Part 121 companies in the Bush at the time RSIA passed: Era Aviation, PenAir and Frontier Flying Service.

Within a few years of the bill’s passage, several Part 135 companies either went out of business or dropped out of scheduled service. As the competitive landscape cleared, Frontier purchased the assets for Cape Smythe Air Service in 2005, which included its North Slope routes, thus initiating an era of nearly nonstop expansion for the Fairbanks-based company. Then another bypass change was announced.

In December 2006, a revision to RSIA was passed which gave Part 121 carriers immediate access to bypass for new bush destinations for a full year regardless of whether they carried any passengers at all. While flying in the face of RSIA’s professed preference for supplementing passenger service, this revision provided an immediate economic advantage to Part 121 operations over their Part 135 competition. Further, the revision allowed the first three Part 121 operators who entered a route to receive a split of an extra 10% of the bypass for that route by reducing the Part 135 and cargo shares. Although the “121 hammer” was removed, with no explanation or compensation to those companies, such as Warbelow’s Air Ventures, that had invested millions into pursuing 121 certification, the damage was done. The USPS had reshaped the aviation industry in Alaska to the direct benefit of the three companies that became part of Ravn Air Group.

In 2008, Frontier and Hageland Aviation merged (branding as “Frontier Alaska”), and one year later, the new company purchased Era Aviation, rebranding then as Era Alaska. (The Ravn Air Group brand arrived in 2014). The Era deal was touted in the Alaska Journal of Commerce as likely bringing the new entity 24 million pounds of mail annually plus revenues of $100 million. Even before the 2018 purchase of PenAir in bankruptcy court, Ravn would cover nearly every corner of Alaska and in many places, as is now apparent, they were enabled to become the only air travel option in town.

In 2015, two of Ravn’s three owners (Jim Tweto and Mike Hageland) were bought out after its CEO, Bob Hajdukovich, secured financing from investor JF Lehman and Co. Lehman then received a majority stake in the company. (A second private equity firm, W. Capital Partners, received a stake as well with the Hajdukovich family retaining a minority percentage.) At the time, former U.S. Sen. Mark Begich, made a prophetic comment on the deal, telling the ADN, "From an aviation standpoint, recapitalization is good news. But the real question here is, what’s their objective? Is it sustainable and long-term?”

Five years later, we have an answer.

Through changes in ownership and management, as federal inspectors cycled in and out, and chief pilots, directors of operation, safety inspectors and directors of maintenance were fired, resigned or replaced, one darker consistency in Ravn’s business practice became pervasive — a relentless litany of accidents. Historically, before Ravn existed, its bush carrier, Hageland Aviation, was in trouble. In the 1990s, Hageland crashed 18 times, and in the 2000s, before the initial merger with Frontier, it crashed 11 more times. Altogether, between 1990 and its most recent accident in January of this year, Hageland Aviation has crashed 43 times, resulting in 29 fatalities and 28 injuries.

Along with the other Ravn carriers, Frontier, Corvus and PenAir, the air group has been in 20 accidents since 2008 — including, most dramatically, last October’s crash in Dutch Harbor which resulted in only the second Part 121 fatality in the entire U.S. during the past decade.

In that same period, Bering Air has been in four accidents, Alaska Central Express has been in four, Alaska Seaplanes has been in three and Warbelow’s Air Ventures has been in one.

In the wake of Hageland’s multiple-fatality accident in St. Marys in 2013, the Federal Aviation Administration revealed numerous shortcomings within the company’s management structure, including an a poor overall safety culture. It was revealed in that investigation that FAA officials had prepared a case to revoke Hageland’s operating certificate, but it was not pursued by their legal arm. FAA personnel also disclosed the $200,000 fund Hageland’s maintained to pay enforcement-related fines.

After the multiple-fatality crash in Togiak in 2016 the FAA discussed with investigators its revised efforts to work with Hageland (and thus Ravn) under a new enforcement method termed “compliance philosophy." This strategy was based on the concept that enforcement only worked on those companies that could not or would not comply. Compliance philosophy, according to the FAA, recognized that companies made inadvertent mistakes. The day the National Transportation Safety Board released the Togiak report — which detailed failures in the cockpit, the company and with FAA oversight — Hageland crashed again.

Following the Dutch Harbor accident, Ravn lost its Capacity Passenger Agreement with Alaska Airlines, which resulted in a sharp reduction in service to the village of Unalaska. The company’s Part 121 on-time performance has struggled over the past several years, and its reputation has suffered from a habit of same-day cancellations. The coronavirus might have been the last straw but, compared with its costly accident record and other concerns, it is not the only factor and in considering all that came before it, the virus likely was not even the most cumulatively destructive.

The long history of Ravn Air Group includes, at its center, four individual operating certificates. Collectively, these companies encompass a huge swath of Alaska’s history and have touched countless lives. In the past decade, they have moved thousands of tons of mail and flown hundreds of thousands of passengers. And yet, on every level that matters, Ravn is proof that the RSIA experiment and FAA oversight have collectively failed Alaskans. While it may have saved the USPS money, the advantages RSIA afforded to Part 121 air carriers directly translated into Ravn’s increased revenues and fueled its ambitious expansion, allowing the company to transform Hageland Aviation into the largest scheduled Part 135 commuter in the U.S. But Ravn’s safety record is nothing less than catastrophic, and despite its dominant industry position it has failed to weather an economic storm that its competitors continue to prudently navigate.

Over the years, Ravn and its cohorts have placed the blame for its crashes on Alaska’s weather, infrastructure and “bush pilot culture." More than once, the company has redirected accountability toward its pilots, maintenance personnel and, in the case of PenAir Flight 3296, the aircraft itself. Unfortunately, Ravn’s many management figures have never attained the level of self-awareness that might have spared its employees the economic devastation of the past few weeks. But one thing is clear: in its determination to increase Part 121 passenger operations, RSIA ushered in the destruction of all of the regional Part 121 passenger carriers in Alaska. Further, through foundational neglect, the FAA now possesses a legacy of injury and death in the state that will reverberate for years.

After all the broken promises and tragedies, it will now be up to those RSIA snubbed so long ago to pick up the pieces and keep the mail moving. And as those Part 135 operators scramble to fill the enormous gaps left by this abrupt bankruptcy, all Alaskans should consider that although the Ravn Air Group story does not begin with the coronavirus, perhaps it is time to accept that this is where it ends.