"Some parties claimed that the campaign environment was restrictive and lacked a level playing field, including access to the media. They complained that they were frequently unable to get their views published in the media and claimed that some media outlets were biased towards FijiFirst. Some of the smaller parties also complained that media outlets were biased towards the larger parties. While the MOG observed bias by some media outlets, as reported above, it concludes that political parties had enough access to the media to enable voters to make an informed decision on Election Day." - MOG Final Report

4.1 Media in Elections

The Constitution of Fiji (section 17) provides for freedom of ‘speech, expression and publication’.

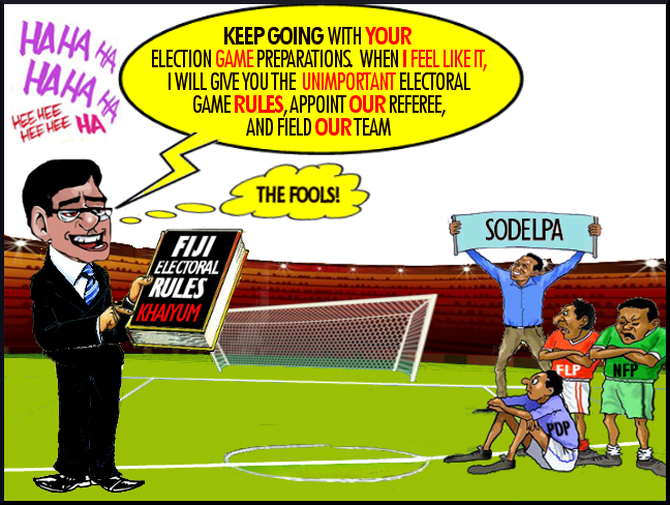

The media in Fiji made good efforts to cover the election and political parties were, to varying degrees, able to communicate their messages to the public. However, the restrictive and vague media framework, including potentially harsh penalties, limited the media’s ability to rigorously examine the claims of candidates and parties. In February 2013, the Government amended the Political Parties Decree and prohibited the media from referring to prospective parties as ‘political parties’ until they were registered.

This included established parties that were seeking re-registration (news organisations faced fines of up to FJ$50,000 or a five-year jail term for violation). There were complaints of media restrictions from some parties, highlighting the threat of penalties under the Media Industry Development Decree 2010. Nevertheless, the press began to report more widely on the political process, including some criticism of the Government. The MOG believes that engagement through the media is essential, in order to encourage public ownership of the electoral process.

The repeal of section 18A of the State Proceedings Act in June 2014, which had conferred comprehensive protections to the Prime Minister and Ministers from prosecution arising from any personal or official statements (and media organisations that reported them), also had a positive impact as it provided a legal solution for those who considered themselves libelled, slandered or defamed.

4.2 Media Industry Development Decree

Media in Fiji is governed by the Media Industry Development Decree 2010. Following the Decree, the Media Industry Development Authority (MIDA) was established in October 2013 as the government body responsible for initiating and prosecuting complaints against the media. The Media Decree sets out the standards for reporting that media outlets are required to comply with, including:

• a duty to be balanced and fair in their treatment of news and current affairs and their dealings with members of the public;

• an obligation to give an opportunity to reply to any individual or organisation on which the medium itself comments editorially; and

• to show fairness at all times, and impartiality and balance in any item or program, series of items or programs or in broadly related articles or programs when presenting news which deals with political matters, current affairs and controversial questions.

In relation to elections in particular, MIDA carried out a number of functions. Most notably the MOG observed MIDA’s role in media accreditation, policing the campaign blackout and ongoing investigative work.

Media Accreditation

The FEO required all media personnel wishing to have access to elections to be accredited. To gain accreditation, media (including international media) had to be registered with MIDA first. The MOG received a number of complaints about this process, which generally related to a lack of clarity over accreditation procedures. The deadline set for submitting applications was considered too early by some media organisations (this was subsequently extended after a suggestion by the MOG) while others were unaware that they had to apply both to MIDA and the FEO for accreditation. The MOG is not, however, aware of any media organisations that applied for accreditation and did not receive it. A statement from MIDA on 15 September said 431 local and 37 international media personnel were registered with MIDA and accredited by the FEO.

Policing the Campaign Blackout

The Electoral Decree gives MIDA authority to investigate any breaches of the 48 hour campaign blackout. The Decree also gives MIDA the power to approve reporting during the blackout period. MIDA provided briefing to local and international media in order to explain the campaign blackout, although many commented that this was unclear. The interpretation of this section of the Electoral Decree was broad, and included any media that could be accessed in Fiji (i.e. any international online media). The burden this placed on MIDA and media organisations was heavy. MIDA did not take any action against media outlets for breaching the blackout and it did not directly hinder reporting of the elections.

Ongoing Investigative Work

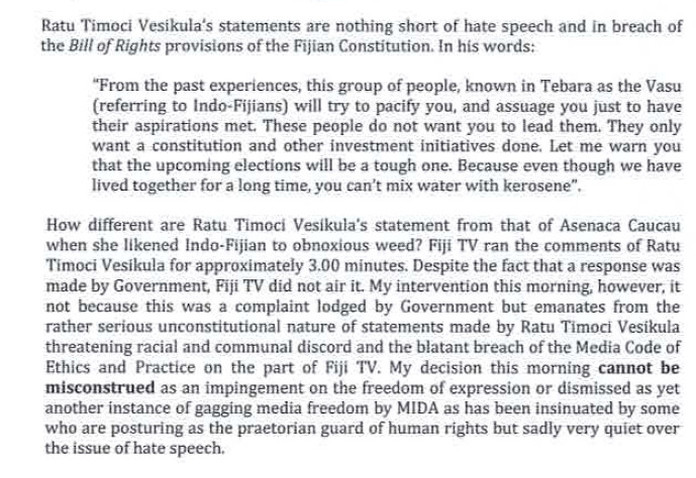

Under the terms of the Media Decree, MIDA has ongoing powers to investigate any complaints made against media organisations. A number of cases were referred to MIDA in the course of the election campaign, including one against a television station for ‘giving unfettered prominence’ to comments by Ratu Timoci Vesikula that were deemed by MIDA to be hate speech, and another against Prime Minister Bainimarama and The Fiji Sun newspaper for comments claiming SODELPA was involved in plotting to release George Speight (convicted for staging a coup in 2000).

Recommendations

• The media accreditation process should be simplified and all media outlets, including international media, should have sufficient advance notice of deadlines and timelines.

• The Media Industry Development Authority should issue clear, timely and practical reporting guidance.

• Penalties for breaching election-related reporting rules should be reviewed.

• Should the Media Industry Development Authority continue its role in future elections, there is a need for an independent institution to adjudicate complaints about its actions, consistent with Fiji’s legal and constitutional framework.

4.3 Effectiveness of Media

The effectiveness of the media to provide informed choice on Election Day varied greatly between the urban and rural areas. Voters in the urban areas had access to a reasonably diverse range of media. As of September 2014, a total of 34 media outlets were officially registered under MIDA, including newspapers, magazines, radio stations, TV stations and social media. Radio is the most important source of information for many Fijians and played a crucial role in distributing information about both the political and administrative aspects of the election. In remote areas, word of mouth was the most common way of disseminating information.

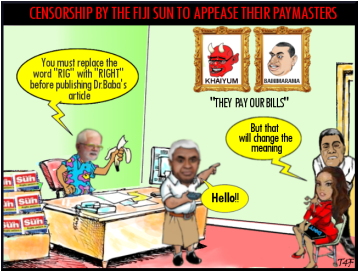

The coverage of the electoral campaign in the final weeks before the election included instances of both neutrality and partiality among the local media. While effort was made by some domestic private media (Fiji One TV, Communications Fiji Limited) to allocate an equitable amount of airtime to the different candidates and political leaders through special election programs, some media organisations appeared to exhibit political biases.

The MOG believes that any public complaint on biased media coverage should be addressed and adjudicated by an independent institution regulated by law. Some parties claimed that the campaign environment was restrictive and lacked a level playing field, including access to the media. They complained that they were frequently unable to get their views published in the media and claimed that some media outlets were biased towards FijiFirst. Some of the smaller parties also complained that media outlets were biased towards the larger parties. While the MOG observed bias by some media outlets, as reported above, it concludes that political parties had enough access to the media to enable voters to make an informed decision on Election Day.

Recommendations

• There is a need for a regulation as well as an independent institution to prevent and adjudicate media biases, thus ensuring a level playing field among election participants.

• The outcome of the 2014 Fijian Election broadly represented the will of the Fijian voters. The conditions were in place for Fijians to exercise their right to vote freely.

• There was strong interest in contesting the election, with 248 candidates from seven political parties and two independent candidates. In general, political parties were able to mobilise and candidates were free to campaign. The campaign period was peaceful.

• Civil society participation in the electoral process was unduly restricted, including because of prohibitions contained in Section 115 of the Electoral Decree 2014.

• The media in Fiji made good efforts to cover the election. Political parties were, to varying degrees, able to communicate their messages to the public. However, the restrictive media framework, including potentially harsh maximum penalties, limited the media’s ability to rigorously examine the claims of candidates and

parties.

• Despite a new, unfamiliar and complex voting system, the Fijian Elections Office (FEO) administered the elections effectively. Polling officials were well-prepared and voting procedures were generally followed correctly. The tasks of political party polling agent education and voter education were complicated by the effect of Section 115(1) of the Electoral Decree.

• Police played an important role in the elections, building confidence and assisting in a neutral manner when needed.

• FEO and the Electoral Commission ran an extensive voter information campaign, which appeared to reach most voters. Some voters in remote areas did not have sufficient access to voter information.

• The counting process, while onerous, appeared well organised and thorough, both at polling stations and at the National Counting and Results Centre. The Multinational Observer Group (MOG) did not observe any significant irregularities in the counting process, but the progress of the count could have

been better communicated to the public.

• The MOG did observe some problems, particularly in voter registration, prepolling and postal voting, which stemmed at least in part from the short preparation time and miscommunication, especially related to pre-polling.

• The election was enthusiastically embraced by the voters of Fiji, who were keen to participate in the democratic process. The MOG observed that the election was conducted in an atmosphere of calm, with an absence of electoral misconduct or evident intimidation.

• No challenges were submitted to the Court of Disputed Returns.