INJECTING MISERY ON NURSES: |

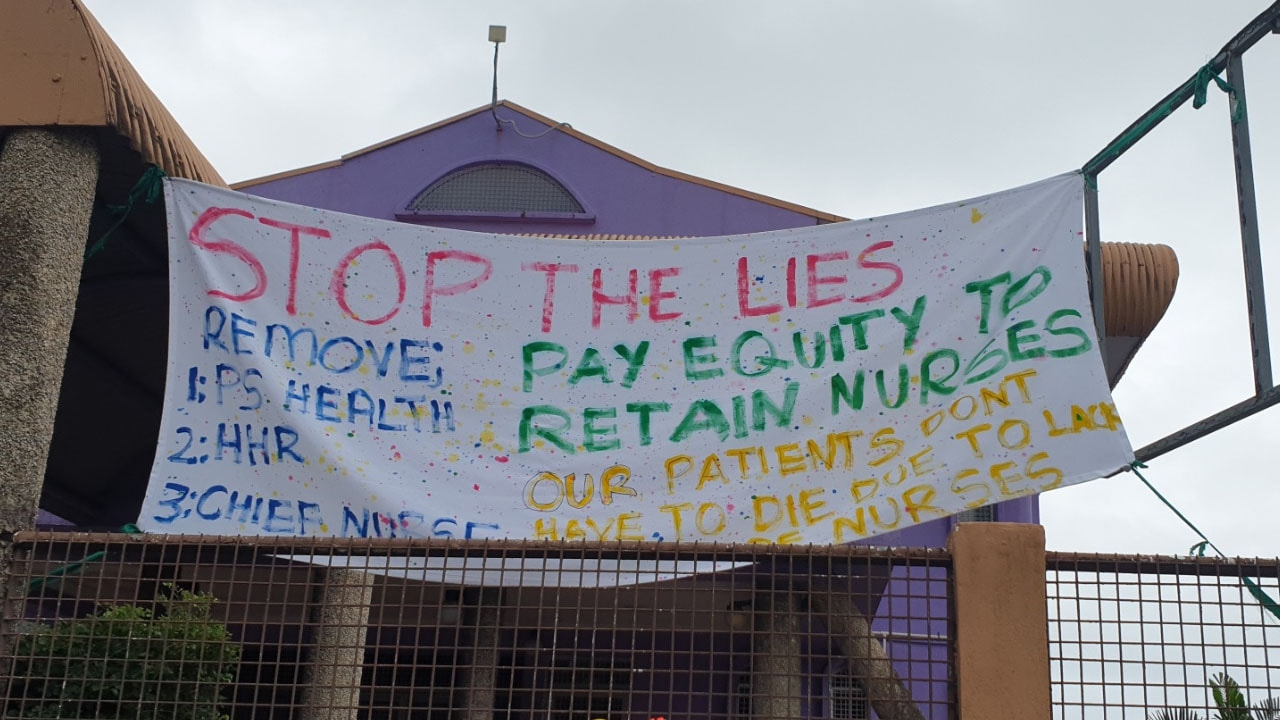

*Fiji Nursing Association is calling for the resignation of the PS Dr James Fong, Director of Human Resources Joe Fuata, and Chief Nurse Colleen Wilson

GADAI

GADAI "Subject: Nurse Strike in Fiji

Summary:

This analysis provides an update of a possible nurse strike in Fiji, including information on the grievances, strike timeline, potential impacts, and recommended actions to mitigate the consequences.

1. Background:

The nurse strike in Fiji is scheduled to commence on Thursday, August 24th, 2023. The primary reason behind the strike is the failure to implement the promised pay rise, which has caused discontent among nursing personnel across the country.

2. Grievances:

Nurses in Fiji are frustrated with the lack of progress in receiving the promised pay rise. The failure to meet wage expectations has led to financial strain on the nurses and their families, affecting morale and motivation in their line of work.

3. Strike Timeline:

- Thursday, August 24th, 2023:

- The strike depends on any change in pay. If there is no adjustment, it will proceed.

- The strike will commence at the Colonial War Memorial Hospital (CWM) in Suva.

- After 2 hours at CWM:

- Labasa Hospital will join the strike.

- After an additional 2 hours at CWM:

- Lautoka Hospital will go on strike.

- Subsequent stage:

- All health centers across Fiji will join the strike.

4. Potential Impacts:

The nurse strike in Fiji could have the following potential impacts:

- Disruption of Healthcare Services:

The strike may significantly disrupt healthcare services in the affected hospitals and health centers. With the withdrawal of nursing staff, remaining healthcare professionals will face challenges in providing adequate care to patients, leading to delays, longer waiting times, and reduced efficiency.

- Increased Workload for Other Health Workers:

Other healthcare workers, including doctors, technicians, and support staff, will experience an increased workload due to the absence of nurses. This additional burden may result in exhaustion, burnout, and compromise the quality of patient care.

- Delayed or Deferred Medical Procedures:

Certain medical procedures, appointments, and surgeries may need to be delayed or postponed until after the strike is resolved. This delay could cause anxiety and potential complications if patients' conditions deteriorate during the waiting period.

- Public Outcry and Pressure on Authorities:

The strike is likely to generate public outcry, particularly if healthcare service disruptions adversely affect patients. The public may put pressure on authorities to address the nurses' demands promptly, leading to negotiations and potential resolution of the dispute.

- Economic Impact:

The strike may also have economic implications. If people forgo seeking medical treatment during this period, it could lead to financial loss for healthcare facilities. Furthermore, prolonging the strike and continuing disruptions in healthcare services may impact tourism, foreign investments, and Fiji's overall economy.

5. Recommended Actions:

To minimize the potential impacts of the nurse strike and ensure the continuation of essential healthcare services, the following actions are recommended:

- Urgent Negotiations:

Authorities should engage in negotiations with the nursing union to address their concerns promptly. Initiating dialogue and finding a mutually satisfactory solution is crucial for resolving the dispute and preventing prolonged disruption to healthcare services.

- Contingency Plans:

Establishing contingency plans to manage the strike's impact is vital. Hospitals and health centers should develop strategies to deploy alternative staffing arrangements, including temporary nurses or reassigning duties to other healthcare professionals, to ensure continued patient care during the strike period.

- Public Communication:

Transparent and timely communication with the public is important. Updates on the strike, alternative healthcare arrangements, and potential disruptions should be conveyed to patients, their families, and the general public to manage expectations and mitigate negative sentiment.

Conclusion:

The nurse strike in Fiji poses a significant threat to healthcare services and the overall well-being of the population. Authorities must take immediate action to address the nurses' concerns, negotiate a resolution, and implement contingency plans to minimize disruptions and ensure the continuity of vital healthcare services.

I want to hear a backbrief on our Contingency Plans this Thursday on how best RFMF can assist our Major Hospitals and Medical Centres, if the nurses' grievances are not heard by the Coalition Govt within their 28 days of notice.

For your nec support and actions.

Manoa

BG

Comd JTFC"

Summary:

This analysis provides an update of a possible nurse strike in Fiji, including information on the grievances, strike timeline, potential impacts, and recommended actions to mitigate the consequences.

1. Background:

The nurse strike in Fiji is scheduled to commence on Thursday, August 24th, 2023. The primary reason behind the strike is the failure to implement the promised pay rise, which has caused discontent among nursing personnel across the country.

2. Grievances:

Nurses in Fiji are frustrated with the lack of progress in receiving the promised pay rise. The failure to meet wage expectations has led to financial strain on the nurses and their families, affecting morale and motivation in their line of work.

3. Strike Timeline:

- Thursday, August 24th, 2023:

- The strike depends on any change in pay. If there is no adjustment, it will proceed.

- The strike will commence at the Colonial War Memorial Hospital (CWM) in Suva.

- After 2 hours at CWM:

- Labasa Hospital will join the strike.

- After an additional 2 hours at CWM:

- Lautoka Hospital will go on strike.

- Subsequent stage:

- All health centers across Fiji will join the strike.

4. Potential Impacts:

The nurse strike in Fiji could have the following potential impacts:

- Disruption of Healthcare Services:

The strike may significantly disrupt healthcare services in the affected hospitals and health centers. With the withdrawal of nursing staff, remaining healthcare professionals will face challenges in providing adequate care to patients, leading to delays, longer waiting times, and reduced efficiency.

- Increased Workload for Other Health Workers:

Other healthcare workers, including doctors, technicians, and support staff, will experience an increased workload due to the absence of nurses. This additional burden may result in exhaustion, burnout, and compromise the quality of patient care.

- Delayed or Deferred Medical Procedures:

Certain medical procedures, appointments, and surgeries may need to be delayed or postponed until after the strike is resolved. This delay could cause anxiety and potential complications if patients' conditions deteriorate during the waiting period.

- Public Outcry and Pressure on Authorities:

The strike is likely to generate public outcry, particularly if healthcare service disruptions adversely affect patients. The public may put pressure on authorities to address the nurses' demands promptly, leading to negotiations and potential resolution of the dispute.

- Economic Impact:

The strike may also have economic implications. If people forgo seeking medical treatment during this period, it could lead to financial loss for healthcare facilities. Furthermore, prolonging the strike and continuing disruptions in healthcare services may impact tourism, foreign investments, and Fiji's overall economy.

5. Recommended Actions:

To minimize the potential impacts of the nurse strike and ensure the continuation of essential healthcare services, the following actions are recommended:

- Urgent Negotiations:

Authorities should engage in negotiations with the nursing union to address their concerns promptly. Initiating dialogue and finding a mutually satisfactory solution is crucial for resolving the dispute and preventing prolonged disruption to healthcare services.

- Contingency Plans:

Establishing contingency plans to manage the strike's impact is vital. Hospitals and health centers should develop strategies to deploy alternative staffing arrangements, including temporary nurses or reassigning duties to other healthcare professionals, to ensure continued patient care during the strike period.

- Public Communication:

Transparent and timely communication with the public is important. Updates on the strike, alternative healthcare arrangements, and potential disruptions should be conveyed to patients, their families, and the general public to manage expectations and mitigate negative sentiment.

Conclusion:

The nurse strike in Fiji poses a significant threat to healthcare services and the overall well-being of the population. Authorities must take immediate action to address the nurses' concerns, negotiate a resolution, and implement contingency plans to minimize disruptions and ensure the continuity of vital healthcare services.

I want to hear a backbrief on our Contingency Plans this Thursday on how best RFMF can assist our Major Hospitals and Medical Centres, if the nurses' grievances are not heard by the Coalition Govt within their 28 days of notice.

For your nec support and actions.

Manoa

BG

Comd JTFC"

From Fijileaks Archive, 29 September 2017

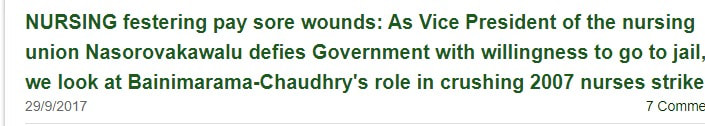

"I wanted to know why nurses always faced pay cuts when a military coup took place. [Bainimarama's Interim Finance Minister] Mahendhra Chaudry blamed me, rather than the government, for the plight of the nurses, and said we should have sorted all this out with the Qarase government rather than raising the issue when finances were in a critical state...On the second day [of the strike], we called upon interim Prime Minister Bainimarama to intervene. He refused. Instead, he said the strike was a ploy to bring down his government, and that the stand-off with the unions could have the effect of deferring the elections planned for 2009. He claimed his government did not have the money to restore the five per cent pay cut. But we wanted proof that the government had no money – there seemed to be plenty available for government ministers to take overseas trips at the taxpayers’ expense."

Kuini Lutua, as general secretary of the Fiji Nursing Association, reflecting on the 2007 "The Fiji Nurses Strike" in The 2006 Military Takeover in Fiji: A Coup to End All Coups? edited by Jon Fraenkel, Stewart Firth, Brij V. Lal

Fiji’s 2006 coup brought to power a government determined to resist industrial action. Seven months after Bainimarama seized power, Fiji’s 1,500 nurses walked out of the country’s hospitals in a strike over pay and conditions. The nurses were aggrieved that the interim government had cut their pay by five per cent (as it had for all other civil servants), lowered the retirement age, and failed to implement a wide-ranging agreement reached with the deposed government of Laisenia Qarase before the 2006 election. The government treated the strikers with contempt, offering one per cent, and then refusing to negotiate further. Exhausted, short of money, and more eager than ever to find jobs overseas, the nurses were forced back to work after sixteen days. Mahendra Chaudhry, despite his credentials as a former union leader, was as dismissive of the nurses’ cause as the military man who had appointed him finance minister. Kuini Lutua, as general secretary of the Fiji Nursing Association, was at the centre of these events, leading the strike, encouraging her members to stand firm – and condemned by Chaudhry and other ministers. She is the author of this first-person account of events. The nurses’ defiance encouraged others to follow suit. Unions affiliated with the Fiji Islands Council of Trade Unions (FICTU) – the Fijian Teachers Association (FTA), the Fiji Public Employees Union, and the Viti National Union of Taukei Workers – walked off the job on 2 August, though without the same solidarity or unity of purpose as the nurses; the teachers called off their strike within a day and other workers held out for only a week. Meanwhile, Taniela Tabu, spokesman for FICTU, was arrested. He later claimed to have been forced to strip to his underwear and humiliated. Military officers, he said, threatened him with death if he were summoned to the barracks again. As Vijay Naidu shows (chapter 11), the strikes revealed deep splits within the Fiji trade union movement. The Fiji Trade Union Congress and its affiliate unions, widely regarded as sympathetic to the coup, had already settled for the one per cent pay increase offered by the government, and offered no assistance to its rival FICTU when FICTU unions went on strike. Bainimarama thought the strikes vindicated his coup. He pointed out that he led a non-elected government, and could therefore resist interest groups in the interest of the country as a whole. ‘We do not have to worry about votes’, he said.

‘This Government is not going to budge.’

By Kuini Lutua

INTRODUCTION

On 5 December 2006, when news of the 2006 coup surfaced, I was with seven senior members of the Fiji Nursing Association (FNA) at our MacGregor Road headquarters. We were practicing presentations of the FNA’s submission on the draft Radium Protection Bill. A special cabinet select committee was scheduled to meet with us at 10am that morning. Just as we left the office to go to Parliament House, mobile phones started ringing as distressed family members called their relatives about the coup and the trouble at the parliamentary complex at Veiuto.

Amongst the callers was my secretary, calling to alert me that there had been a military coup and that the cabinet select committee meeting had been postponed until further notice. We returned to the conference hall, and I conveyed to my colleagues what had happened. As we sat down, one of the nurses tapped my back and said, let us pray and not worry. I don’t know how my heart cried out that day as we prayed. All I can remember is that after a very long time I heard myself saying ‘amen’ in unison with my colleagues. We hugged each other, and then the other FNA leaders returned to their jobs at the CWM Hospital. The 2006 coup left the FNA in a difficult position. We had negotiated concessions from the now deposed government of Laisenia Qarase, but these had not yet been implemented. Would they be honoured by the post-coup administration? What would be the result of the inevitable economic decline that invariably follows Fiji’s coups, and the cutbacks in civil service pay that have also been a familiar feature of post-coup policy-making? What kind of solidarity could be

expected from other trades unions in negotiations with the post-coup interim government? This chapter looks at the background to the nurses’ strike of July–August 2007, at the fissures that emerged amongst the trades unions, and at the confrontation between the nurses and the interim cabinet

The signed partnership agreement and memorandum of agreement

The FNA, together with members of the Confederation of Public Sector Unions (CPSU – comprising the Fiji Public Service Association [FPSA] and Fiji Teachers Union [FTU]), had, after some hard negotiation, on 26 April 2006, signed a partnership agreement with Prime Minister Qarase, the chairman of the Public Service Commission (PSC), Mr Stuart Huggett, and its secretary, Anare Jale; it culminated in a five year Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) that established an Industrial Relations Framework (IRF) set to run from 2006 to 2008. The MoA contained clauses that were to resolve industrial relations issues dating back to 2003; to give back to the members of the FNA and other public servants most of the outstanding payments of increments and scheduled cost of living adjustments; and entailed some commitment to the implementation of the 2003 Mercer Job Evaluation Exercise recommendations.

I was thrilled, knowing that with the agreement and the MoA, I could now leave the FNA when my contract expired and seek less stressful jobs. What I had set out to do for the nurses seemed to be finally materializing. The Qarase government had accepted the need for some redress to cover the loss of salaries that civil servants had experienced in the wake of the 2000 coup. This acceptance had come as a surprise to the FNA because a few of the ministers in the Qarase government had labeled civil servants as ‘dead wood’, ‘under-performing’, or ‘time-wasters’. There was seldom a good word about the dedicated service of those who worked tirelessly to fulfill the wishes of these ministers and provide essential services to the public. This change in attitude indicated an emerging awareness that only civil servants could implement government’s political strategies. For the FNA, the negotiations that led up to the signing of the partnership agreement showed the importance of presenting a strong and water-tight case to the government, buttressed by robust facts and figures, in order to convince ministers that taking better care of public sector workers would give the workers an incentive to work harder and more productively. It was also pointed out during the negotiations that it was mainly civil servants who suffered financial hardship each time there was a coup.

The 2000 coup happened shortly after the conclusion of a previous strike by the nurses. Some people to this day still blame the nurses for that coup, saying that they had, prior to the takeover, staged a protest to ensure that the Mahendra Chaudhry-led government would fall. These same people, however, forget that two strong women supporters of the Fiji Labour Party were past executives of the FNA and that, prior to the 2000 coup, they still had much influence over the running of the Association. The May 2000 strike was a result of legitimate industrial grievances: it was not a politically orchestrated attempt to destabilize the Chaudhry government. As a result of that strike, the PSC ordered a salary review, and the nurses went back to work, while their dispute was referred to arbitration. They then accepted without question an Award by permanent arbitrator Jon Apted. Little did they know that problems would arise during the implementation period: The PSC and Ministry of Health repeated their mistake of 1998 – the salaries of the nurses and medical orderlies were wrongly assimilated to the salary scale recommended in 1993. Salary levels had since been adjusted to add three more levels, so the change in salary should have entailed a movement across rather than downwards.The members were upset and angry about this unfair treatment. Although the dollar value of their new salaries was often higher, they found that they had lost, on average, two to four increment levels once they were moved to the new scale. To make matters worse, all civil servants had been denied annual increments because the government had frozen increments. Many of the members had remained on the same salary level for the previous four or five years of

service, some for even longer.

When new graduates came into the workforce after 2000, the more senior nurses – including those who had graduated a year or two earlier – found themselves on the same salary as the newcomers. Many tendered their resignations and looked outside the Ministry of Health for employment. Some migrated overseas. More than 20 nurses moved on to the newly opened Suva Private Hospital and some joined the Military Hospital where they were offered a better salary packet. Some who remained in the public sector workforce, resigned from the FNA

because there was no response from its officials, the Ministry of Health or the PSC in relation to their salary grievances. The FNA lost a considerable number of members in this period. Many members started criticizing the Association’s leaders, but it was difficult to ascertain the real cause of the dissension of members at the time. Migration overseas of nurses was to become an evermore pressing issue in the wake of the 2000 coup. In addition to long-established destinations – like Australia, New Zealand and England – new destinations – like Bermuda and the Bahamas – actively sought to recruit nurses from Fiji. Other Pacific Islands – such as the Marshall Islands, Palau and the Cook Islands – had formerly recruited Fiji nurses, but pay-rates in the Pacific have become uncompetitive compared with those on offer from the newer destinations. One of the barriers to the movement of Fiji nurses overseas has always been the need for prospective migrants to pay the airfares. But recruiters from the Caribbean now offer packages that include air travel costs, thereby generating the potential for a much more substantial drain of nursing talent from Fiji in future years.

As in May 2000, nurses went on strike in 2005 over the issue of wrong assimilation of salaries for nurses who had graduated before 2000. Some were earning between F$9,000 to F$11,000 when they should have been earning F$14,000 to F$16,000. Payroll had been part of my responsibility when I was with my previous employer, the Reserve Bank of Fiji. I was well aware of the effects of payments of annual increments and the importance of workers getting the correct movement in salary when promotions and acting allowances were paid. It was not too difficult for me to see that there was something seriously wrong with the salaries that the nurses were being paid. There were continuous complaints from members that they had been on a higher salary before the salary adjustment of 2000/2001. My first task when I became the FNA General Secretary in September 2001 was to listen to the members tell me their stories about the unfairness of the 2000 salary review and the subsequent award. Checking the files and getting salary slips and letters of appointment from members, I discovered that, it was not only those who had commenced their careers shortly before 2000 that were affected, but also those who had started well before 1998. I began to work with the office staff to build up case histories for all members that brought up salary grievances. After a while, we were able to detect a pattern in the salary treatment of staff nurses who had graduated in the same year and those who had been promoted in the same year.

We found that many of these senior nurses had lost out on the higher salary that should have accompanied promotion because their salary before promotion had been determined at the wrong level. This generated widespread disillusionment and lack of incentive to work hard, beyond the common compassion of nurses to provide care for the sake of saving lives. Some of the nurses turned to the teachings of the Nurses Christian Fellowship, which urged them to forsake strike action and preached ‘you do not ask for your pay, because nursing is a calling from God’. Some would say to the junior nurses, ‘one day your pay will be put right but you must not refuse to do good because your pay is low – you just provide the service’. In 2006, this unsatisfactory situation appeared to have reached some resolution. The correct salary adjustments were finally calculated for most nurses. For some, this was on the eve of their retirement. There may be others who retired on the wrong salary. I had to constantly negotiate with Anare Jale who was then secretary to the Public Service Commission, and Stuart Huggett who was its chairman. Having someone from the private sector as the chair of the PSC brought some useful experience to the position, and enabled the government to finally acknowledge the great injustice that had been done to those employed in the civil service. I have a sister who was holding a senior technical civil service post.

When I shared with her the story of the regular transfer of nurses to the wrong position on the new salary scale, she confirmed that it was the same for all the other civil servants. She added that it hurt the technical staff in the different ministries to be so treated: they know that they are qualified people, have been trained for at least three years and have specialist skills and competencies that are essential for the core services of government. Yet their remuneration has not moved upwards in the way that had been settled during previous negotiations

between government and the public sector unions. In the aftermath of the 2006 coup, in early 2007, the interim government declared to the media that there would be a 10 per cent pay cut for all civil servants. The FNA and CPSU members approached new PSC chair Rishi Ram to confirm what the media was reporting. He denied the news reports. He said that there was no confirmed reduction but it was likely that the partnership agreement and MoA would be affected by the change in government. This was no surprise to us, given the bitter experience of civil servants after the 1987 and 2000 coups. The timing was dreadful from the public service employees’ point of view: there was to have been some salary increase for the civil servants in the last pay of

December 2006, and another 2 per cent adjustment in the beginning of 2007. In mid-2006, there had been agreement for a delayed staggered payment of 2 per cent arising from the agreement between the trade unions representing the civil servants and the Qarase government. This all changed after the December 2006

coup. At first, it was said that the balance of payment due for the three year IRF, covering 2005 to 2007, would be paid sometime in 2007. That never eventuated. Nurses had good reason to feel aggrieved.

When the negotiations with the PSC became no longer fruitful, the CPSU agreed that members would vote on the separate issues affecting each of the public sector unions. In addition to the broader issues, the FNA had an ongoing dispute about the 12-hour shift that was being imposed on nurses by the CWM Hospital management. Although several meetings had taken place with the Ministry of Health representatives and the PSC, the FNA was not satisfied with the outcome of the talks and sought the intervention of the Minister for Health, Dr Jona Senilagakali. Fortunately, he decided in our favour, agreeing, on the basis of evidence that we presented to his ministry, that such shifts were not feasible. The FNA conducted a secret ballot on the five issues affecting our members in March 2007, with the results being declared on 28 April at the 50th Annual General Meeting of the Fiji Nursing Association at the Tradewinds Hotel in Lami, on Suva’s outskirts. There was an overwhelming response from the members, with 875 votes cast on all five issues. At the final count, 89 per cent of votes were in favour of taking industrial action – (i) against the 5 per cent salary reduction; (ii) for not honouring the partnership agreement; (iii) for not honouring the MoA signed with the previous Qarase government; (iv) for the breach of the collective agreement on the reduction of the compulsory retirement age from 60 years to 55 years; and, (v) for the imposition of a 12-hour shift for nurses who worked in hospitals.

A trade dispute was lodged on 21 June 2007 with the Ministry of Labour, Industrial Relations and Tourism, through its permanent secretary, Taito Waqa, indicating the cause of the dispute, the results of the secret ballot and the intended date for industrial action (midnight 24 July 2007). As our members worked in essential services, we had to give 28 days notice to the ministry of our intention to take industrial action. The intention of this law, I believe, was to give the relevant ministries enough time to intervene through a dispute committee or mediation process to try to settle the matter amicably.

The FNA then waited for a reply to our notification. We knew that we had followed the rules to the letter, but we received only a reply that the dispute was being analyzed. Even before we knew the result of the secret ballot, the interim Minister for Labour, Industrial Relations and Tourism, Bernadette Rounds Ganilau, had sent me a copy of a letter addressed to the general secretary of the Public Service Association, Rajeshwar Singh, requesting his attendance at a meeting aimed at mediation with the trade unions that were contemplating filing

trade disputes. I immediately sent a reply to her, stating that dialogue was of no use to us because our grievances were already under consideration by our membership through the secret ballot. At that stage, we in the leadership of the FNA were not sure whether or not our members would want to stage industrial

action. I was not happy with the way that the FNA was addressed in the correspondence. It seemed to me that our invitation to the mediation meeting was an afterthought. Furthermore, we did not want to start premature dialogue that might compromise our position. It was the minister herself who wanted to mediate. However, there

are appointed officers in the Ministry of Labour who are trained to do this job. In my opinion, the minister has the last say and is the final decision-maker. For the minister to intervene in person at this early stage would have been a waste of time for us as well as her. Nevertheless, other trade unions decided to meet her for this mediation process. The media later reported that these efforts were not successful.

The countdown for the industrial action started when the trade dispute was lodged. Internally, FNA president Simione Racolo called for an emergency meeting of the FNA national council. At this meeting, we informed the council of the process that was to take place; about the results of the negotiations that we had been having with the PSC; and about the involvement of the permanent secretary for health, Dr Lepani Waqatakirewa. The members were told to prepare their colleagues by updating them weekly on the progress of the talks with the

interim government. As general secretary, I was to be in contact with them if some positive changes seemed likely to materialize. The presidents of all the FNA branches were asked to keep talking to members, encouraging them to keep working normally with the patients. For those who worked in weekly or monthly clinics, they were to be told that, if there were to be industrial action, they were not to come to the health centres or hospitals, but to take a supply of drugs for patients to cover that period. The branch presidents were reminded to choose their picket sites carefully so that they were not on government premises. If picket sites were in public places, the owner of the land was to be approached traditionally. Picket sites in Fijian villages were discouraged, to avoid any appearance of ethnic bias. Ours is a multiracial union, and we did not want to seem dependent on traditional Fijian support. (Sometimes this was unavoidable; in Tavua, for example, the

turaga ni vanua insisted that it was his duty and that of his warriors to protect the nurses.) Other plans included assembly and distribution of the cell-phone numbers of contacts at the branch level because we were not to use the government phones. The FNA national council met to decide on the financial assistance to be given to branches that needed it. In past strikes, we had found it necessary to look after striking members only for two or three days. Judged by our previous strike experiences, we were very optimistic.

A week or two before the 24 July, when the nurses’ strike was scheduled to commence, I continued talks with my counterparts, Agni Deo Singh, the general secretary of Fiji Teachers Union, and Rajeshwar Singh, the general secretary of the Fiji Public Service Association. Together, we tried to negotiate with interim Minister for Public Sector Reform Poseci Bune. This man, I thought, did not know what he was talking about – we found what he was offering absurd because he made no commitment to any movement in the interim government’s position despite being aware that all three of our unions had lodged trade disputes with the Ministry of Labour. He also made it difficult for us to meet him – for example, at one point, giving excuses that he was not in Suva and that we would have to wait until he returned after the weekend.

Meanwhile, our 28 days notice deadline was closing in and we had not made any progress. Rajeshwar Singh again made arrangements with the CPSU to meet the ‘money man’ Mahendra Chaudhry. This arrangement, I believe, was made through Felix Anthony, the general secretary of the Fiji Trade Union Congress (FTUC). By this time, there was a rumour that the FTUC was backing the interim government and that the unions that were affiliated with this organization would not stage any industrial action while the interim government was in power. I do not know how true this was but there were mixed feelings amongst the FTUC affiliates – some of them supported us later on during the strike. We met the interim Minister for Finance at his office on 9 July 2007. This was after the CPSU had met with Poseci Bune earlier on the same day. That afternoon, the CPSU leaders were called to meet with the interim Minister for Finance at the FTUC building to finalize what had been discussed with Rajeshwar Singh at the interim Finance Minister’s office earlier in that day.

During those discussions I was uneasy and sensed that my fellow trade unionists had sold us out because I did not hear any change in the initial offer that the interim government had made to settle our trade dispute. Personally, I wanted to vomit. I couldn’t believe that my colleagues and ‘brother trade unionists’ had embraced defeat by accepting the deal from government without any struggle at all. They had told me that the secret ballots conducted amongst their members had delivered over 90 per cent in favour of industrial action. I could not understand how easily they could change their tune on that day. I prayed that evening as we sat late into the night at the FTUC office, and resolved not to sign any agreement until I had consulted with Simone Racolo and the Suva-based National Council. Some of my colleagues were disappointed by my decision. On 12 June 2007, together with CPSU leaders Rajeshwar Singh and Agni Deo Singh, I met with interim Prime Minister Bainimarama to try to convince him that the policies that they intended to apply to the civil servants would damage the public sector and create a very negative image of the interim government’s leadership, jeopardizing their claims to bring positive change to the country.

Our three unions met more regularly after the nurses’ trade dispute had been lodged, but it became ever clearer that the FPSA and FTA were not committed to strike action or solidarity with the nurses. A week after our dispute was lodged, I met the interim Minister for Commerce, Taito Waradi, and his ministry’s permanent secretary, Mr Yauvoli. Mr Waradi was also acting Minister for the Public Service Commission. He had been informed of our dispute and wanted to talk to me regarding how best our issues could be addressed. I agreed to see him partly because we had been classmates at the Dudley High School in 1970, and because Mr Yauvoli’s wife was a personal friend. At that meeting, I pointed out to both Mr Waradi and Mr Yauvoli the importance to us of the agreement and the MoA. I was afraid that if the interim government did not honour them, it would cause nurses to take industrial action. These were very important agreements for both salaried and wage-earning civil servants. If they were to throw these agreements out, I told them, I was afraid to think of the consequences.

Mr Waradi suggested that perhaps the interim government might shelve or defer the implementation of its planned course of action. I responded that the impact of this would depend on how it was announced to the public and how we in the trade union leadership might explain the interim government’s intentions to our members. I emphasized the fact that the two agreements contained commitments by the government to pay the lost salaries and wages of civil servants who had been in government employment since 2001. In total, the agreements entailed a salary increase of around 27 per cent even without adjustment for the fact that the entire civil service had not received a full increment since 2000. Only about seven per cent of what was contained in the agreement and MoA had been paid by January 2006. Normal increments averaged three per cent for other civil servants. The other important issues were the implementation of the 2003 Mercer Job Evaluation recommendations; the implementation of the intended Performance Management System (PMS) and the job-related allowances; and the need to address the unions’ 2003 log of claims. In the MoA, the issues specific to nurses were: the re-introduction of higher pay for higher professional qualifications and scarce skills; the provision for housing for nurses and medical orderlies or payment of lodging allowance in lieu of housing; and the payment of risk allowance to nurses and medical orderlies who work in high risk areas. These were very important issues for the nurses and had been continually raised at FNA annual general meetings. Even if nurses’ pay remained low, improved working conditions – such as provision of rent-free housing – would discourage many nurses from leaving Fiji.

On 10 July 2007, I called the FNA president and the two Suva-based council members to update them on an offer from interim Finance Minister Mahendra Chaudhry – a restoration of 1 per cent of the proposed 5 per cent pay-cuts in December 2007. I explained my position and I also reminded them about the mandate we had from the members. I wanted to hear their views on the way forward for me as the FNA’s chief negotiator. By this point, I suspected that we were alone in our fight, as the other trade unions had their own issues to think about, and because their mandate from their members was not clear. The president ordered an emergency meeting on 21 July of the full national council so that we could inform them of what had transpired and seek their reaction. The FNA president and I had sought the intervention of the interim Minister for the Public Service Commission as the end of the 28-day notice period drew near. We sat twice with the Permanent Secretary for Health and the Secretary to the PSC on 20 July to try and come to a consensus. At the special national council meeting at the FNA Conference Hall on 21 July 2007, reports from most national council members were presented. Not one of them indicated a negative response to the strike action. While all this was going on, I was involved in a big project with the European Union; it was to start with workshops in Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. I used these opportunities to meet the members and talk to them about what might transpire, and I also gauged their feedback on the strength of resolve in the different branches. One message that we emphasized was ‘explain to your husband/wife and family members why we have to take strike action, so that they will support

you’. We did not know how long the scheduled strike would last, but, because there would be no pay for a number of days, we needed their understanding and cooperation. We had very able and committed national council members representing the 20 FNA branches, and they were very aware of the difficulties that we would face by making a stand on our own. Our CPSU team had broken up and I respected the decisions that my colleagues had taken. I had to brace myself for the outcome of the FNA emergency meeting of 21 July 2007.

After that, there was no turning back. The president and I had received warnings, and even threats, that we couldn’t back out at that stage as the response from the branch representatives was overwhelming. We knew that, because many of our members were married to members of the security forces, they might face severe pressure to back down; but the word from many of them was ‘they became nurses first and got married later’. Many of these brave women and men came out on strike when the clock struck midnight on 24 July 2007. The media and members of the security forces continued to hound me and the FNA president around the clock for comments and explanations. Other members of the national council were also pestered by members of the security forces near their workplace. However, we handled this professionally. There were two incidents of violence reported to us involving members being manhandled by their spouses; we allowed these members to go back to work for their own safety.

On the first day, more than 1,000 nurses were reported to be at the 20 picket sites. Others joined in on the second and third days. Even some non-members joined in and, as they did so, filled in FNA membership forms at the different strike sites around the country. On the second day, we called upon interim Prime Minister Bainimarama to intervene. He refused. Instead, he said the strike was a ploy to bring down his government, and that the stand-off with the unions could have the effect of deferring the elections planned for 2009. He claimed his government did not have the money to restore the five per cent pay cut. But we wanted proof that the government had no money – there seemed to be plenty available for government ministers to take overseas trips at the taxpayers’ expense. In the first few days of the strike it looked as if we might get somewhere; interim

Minister for Labour Bernadette Rounds Ganilau kept promising that concessions would be made and that the dispute could be settled. She admitted that our strike was legal, but she was too intimidated by the interim prime minister to take action and make a decision in our favour, and so she kept delaying.

Whatever authority she had over industrial disputes was taken away from her by Bainimarama, who was determined that our strike should fail. Our initial request to government had been that they should restore the one per cent immediately, restore two per cent in December 2007 and the remaining two per cent in 2008, but once the strike began we went back to demanding the full five per cent. In the end, Bainimarama offered us one per cent, with further discussions to take place over the remaining four per cent. We had been down that road too many times before and we were not fooled. What that meant was nothing beyond one per cent. The truth was that, going back to 2003, we were actually owed a pay increase of 27 per cent. Talking to the media, I pointed out that there was a vast imbalance between the work we did and the amount we were paid, and I wanted to know why nurses always faced pay cuts when a military coup took place.

Mahendhra Chaudry blamed me, rather than the government, for the plight of the nurses, and said we should have sorted all this out with the Qarase government rather than raising the issue when finances were in a critical state. Fiji Human Rights Commission director Shaista Shameem said the right to life of patients, sick people and the elderly was more important than the right to strike, to which I replied that these were not normal times and that our hands had been forced by poor working conditions and low pay. Ultimately, I said, the right to life was the responsibility of the government, not of the nurses. The Methodist Church, possibly Fiji’s largest and most important institution outside government, refused to help the interim government when asked for assistance. Church president Reverend Laisiasa Ratabacaca said the government

was responsible for the situation and that the church would not interfere.

We had to tighten security at our headquarters in MacGregor Road because we thought the strike might attract people who would use our struggle for their own political purposes. Our concern, as I kept telling the media, related purely to nurses’ issues, and the interim government, which was in charge of the country, should not be surprised if all sorts of problems arose. ‘Every coup’, I pointed out, ‘sets a country back 10 years and I hope the prime minister doesn’t forget it’. On 2 August I told the media ‘We have reached day nine and now there is no turning back. Our members have indicated there is nothing stopping them from carrying on in order to get their five per cent back’. I called on the nurses who were still working to join the strike: ‘As long as some nurses remain in hospitals’, I said, ‘this fight will go on. If all members come out and sit, then we will prove to the interim government that nurses are vital in order to have the hospitals functioning.

Nurses must unite and take industrial action’.

By 8 August, however, we realized that the interim government was willing to let Fiji’s hospitals and health system collapse rather than yield to our demands. We had held together for more than two weeks. We had strengthened each other at the picket sites with chain prayers and singing, and people had helped us, but we could not hold out indefinitely because we had no savings. Fiji’s nurses are not prosperous. It was impossible for them to accumulate sufficient savings to survive through a long-running strike.

‘This Government is not going to budge.’

By Kuini Lutua

INTRODUCTION

On 5 December 2006, when news of the 2006 coup surfaced, I was with seven senior members of the Fiji Nursing Association (FNA) at our MacGregor Road headquarters. We were practicing presentations of the FNA’s submission on the draft Radium Protection Bill. A special cabinet select committee was scheduled to meet with us at 10am that morning. Just as we left the office to go to Parliament House, mobile phones started ringing as distressed family members called their relatives about the coup and the trouble at the parliamentary complex at Veiuto.

Amongst the callers was my secretary, calling to alert me that there had been a military coup and that the cabinet select committee meeting had been postponed until further notice. We returned to the conference hall, and I conveyed to my colleagues what had happened. As we sat down, one of the nurses tapped my back and said, let us pray and not worry. I don’t know how my heart cried out that day as we prayed. All I can remember is that after a very long time I heard myself saying ‘amen’ in unison with my colleagues. We hugged each other, and then the other FNA leaders returned to their jobs at the CWM Hospital. The 2006 coup left the FNA in a difficult position. We had negotiated concessions from the now deposed government of Laisenia Qarase, but these had not yet been implemented. Would they be honoured by the post-coup administration? What would be the result of the inevitable economic decline that invariably follows Fiji’s coups, and the cutbacks in civil service pay that have also been a familiar feature of post-coup policy-making? What kind of solidarity could be

expected from other trades unions in negotiations with the post-coup interim government? This chapter looks at the background to the nurses’ strike of July–August 2007, at the fissures that emerged amongst the trades unions, and at the confrontation between the nurses and the interim cabinet

The signed partnership agreement and memorandum of agreement

The FNA, together with members of the Confederation of Public Sector Unions (CPSU – comprising the Fiji Public Service Association [FPSA] and Fiji Teachers Union [FTU]), had, after some hard negotiation, on 26 April 2006, signed a partnership agreement with Prime Minister Qarase, the chairman of the Public Service Commission (PSC), Mr Stuart Huggett, and its secretary, Anare Jale; it culminated in a five year Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) that established an Industrial Relations Framework (IRF) set to run from 2006 to 2008. The MoA contained clauses that were to resolve industrial relations issues dating back to 2003; to give back to the members of the FNA and other public servants most of the outstanding payments of increments and scheduled cost of living adjustments; and entailed some commitment to the implementation of the 2003 Mercer Job Evaluation Exercise recommendations.

I was thrilled, knowing that with the agreement and the MoA, I could now leave the FNA when my contract expired and seek less stressful jobs. What I had set out to do for the nurses seemed to be finally materializing. The Qarase government had accepted the need for some redress to cover the loss of salaries that civil servants had experienced in the wake of the 2000 coup. This acceptance had come as a surprise to the FNA because a few of the ministers in the Qarase government had labeled civil servants as ‘dead wood’, ‘under-performing’, or ‘time-wasters’. There was seldom a good word about the dedicated service of those who worked tirelessly to fulfill the wishes of these ministers and provide essential services to the public. This change in attitude indicated an emerging awareness that only civil servants could implement government’s political strategies. For the FNA, the negotiations that led up to the signing of the partnership agreement showed the importance of presenting a strong and water-tight case to the government, buttressed by robust facts and figures, in order to convince ministers that taking better care of public sector workers would give the workers an incentive to work harder and more productively. It was also pointed out during the negotiations that it was mainly civil servants who suffered financial hardship each time there was a coup.

The 2000 coup happened shortly after the conclusion of a previous strike by the nurses. Some people to this day still blame the nurses for that coup, saying that they had, prior to the takeover, staged a protest to ensure that the Mahendra Chaudhry-led government would fall. These same people, however, forget that two strong women supporters of the Fiji Labour Party were past executives of the FNA and that, prior to the 2000 coup, they still had much influence over the running of the Association. The May 2000 strike was a result of legitimate industrial grievances: it was not a politically orchestrated attempt to destabilize the Chaudhry government. As a result of that strike, the PSC ordered a salary review, and the nurses went back to work, while their dispute was referred to arbitration. They then accepted without question an Award by permanent arbitrator Jon Apted. Little did they know that problems would arise during the implementation period: The PSC and Ministry of Health repeated their mistake of 1998 – the salaries of the nurses and medical orderlies were wrongly assimilated to the salary scale recommended in 1993. Salary levels had since been adjusted to add three more levels, so the change in salary should have entailed a movement across rather than downwards.The members were upset and angry about this unfair treatment. Although the dollar value of their new salaries was often higher, they found that they had lost, on average, two to four increment levels once they were moved to the new scale. To make matters worse, all civil servants had been denied annual increments because the government had frozen increments. Many of the members had remained on the same salary level for the previous four or five years of

service, some for even longer.

When new graduates came into the workforce after 2000, the more senior nurses – including those who had graduated a year or two earlier – found themselves on the same salary as the newcomers. Many tendered their resignations and looked outside the Ministry of Health for employment. Some migrated overseas. More than 20 nurses moved on to the newly opened Suva Private Hospital and some joined the Military Hospital where they were offered a better salary packet. Some who remained in the public sector workforce, resigned from the FNA

because there was no response from its officials, the Ministry of Health or the PSC in relation to their salary grievances. The FNA lost a considerable number of members in this period. Many members started criticizing the Association’s leaders, but it was difficult to ascertain the real cause of the dissension of members at the time. Migration overseas of nurses was to become an evermore pressing issue in the wake of the 2000 coup. In addition to long-established destinations – like Australia, New Zealand and England – new destinations – like Bermuda and the Bahamas – actively sought to recruit nurses from Fiji. Other Pacific Islands – such as the Marshall Islands, Palau and the Cook Islands – had formerly recruited Fiji nurses, but pay-rates in the Pacific have become uncompetitive compared with those on offer from the newer destinations. One of the barriers to the movement of Fiji nurses overseas has always been the need for prospective migrants to pay the airfares. But recruiters from the Caribbean now offer packages that include air travel costs, thereby generating the potential for a much more substantial drain of nursing talent from Fiji in future years.

As in May 2000, nurses went on strike in 2005 over the issue of wrong assimilation of salaries for nurses who had graduated before 2000. Some were earning between F$9,000 to F$11,000 when they should have been earning F$14,000 to F$16,000. Payroll had been part of my responsibility when I was with my previous employer, the Reserve Bank of Fiji. I was well aware of the effects of payments of annual increments and the importance of workers getting the correct movement in salary when promotions and acting allowances were paid. It was not too difficult for me to see that there was something seriously wrong with the salaries that the nurses were being paid. There were continuous complaints from members that they had been on a higher salary before the salary adjustment of 2000/2001. My first task when I became the FNA General Secretary in September 2001 was to listen to the members tell me their stories about the unfairness of the 2000 salary review and the subsequent award. Checking the files and getting salary slips and letters of appointment from members, I discovered that, it was not only those who had commenced their careers shortly before 2000 that were affected, but also those who had started well before 1998. I began to work with the office staff to build up case histories for all members that brought up salary grievances. After a while, we were able to detect a pattern in the salary treatment of staff nurses who had graduated in the same year and those who had been promoted in the same year.

We found that many of these senior nurses had lost out on the higher salary that should have accompanied promotion because their salary before promotion had been determined at the wrong level. This generated widespread disillusionment and lack of incentive to work hard, beyond the common compassion of nurses to provide care for the sake of saving lives. Some of the nurses turned to the teachings of the Nurses Christian Fellowship, which urged them to forsake strike action and preached ‘you do not ask for your pay, because nursing is a calling from God’. Some would say to the junior nurses, ‘one day your pay will be put right but you must not refuse to do good because your pay is low – you just provide the service’. In 2006, this unsatisfactory situation appeared to have reached some resolution. The correct salary adjustments were finally calculated for most nurses. For some, this was on the eve of their retirement. There may be others who retired on the wrong salary. I had to constantly negotiate with Anare Jale who was then secretary to the Public Service Commission, and Stuart Huggett who was its chairman. Having someone from the private sector as the chair of the PSC brought some useful experience to the position, and enabled the government to finally acknowledge the great injustice that had been done to those employed in the civil service. I have a sister who was holding a senior technical civil service post.

When I shared with her the story of the regular transfer of nurses to the wrong position on the new salary scale, she confirmed that it was the same for all the other civil servants. She added that it hurt the technical staff in the different ministries to be so treated: they know that they are qualified people, have been trained for at least three years and have specialist skills and competencies that are essential for the core services of government. Yet their remuneration has not moved upwards in the way that had been settled during previous negotiations

between government and the public sector unions. In the aftermath of the 2006 coup, in early 2007, the interim government declared to the media that there would be a 10 per cent pay cut for all civil servants. The FNA and CPSU members approached new PSC chair Rishi Ram to confirm what the media was reporting. He denied the news reports. He said that there was no confirmed reduction but it was likely that the partnership agreement and MoA would be affected by the change in government. This was no surprise to us, given the bitter experience of civil servants after the 1987 and 2000 coups. The timing was dreadful from the public service employees’ point of view: there was to have been some salary increase for the civil servants in the last pay of

December 2006, and another 2 per cent adjustment in the beginning of 2007. In mid-2006, there had been agreement for a delayed staggered payment of 2 per cent arising from the agreement between the trade unions representing the civil servants and the Qarase government. This all changed after the December 2006

coup. At first, it was said that the balance of payment due for the three year IRF, covering 2005 to 2007, would be paid sometime in 2007. That never eventuated. Nurses had good reason to feel aggrieved.

When the negotiations with the PSC became no longer fruitful, the CPSU agreed that members would vote on the separate issues affecting each of the public sector unions. In addition to the broader issues, the FNA had an ongoing dispute about the 12-hour shift that was being imposed on nurses by the CWM Hospital management. Although several meetings had taken place with the Ministry of Health representatives and the PSC, the FNA was not satisfied with the outcome of the talks and sought the intervention of the Minister for Health, Dr Jona Senilagakali. Fortunately, he decided in our favour, agreeing, on the basis of evidence that we presented to his ministry, that such shifts were not feasible. The FNA conducted a secret ballot on the five issues affecting our members in March 2007, with the results being declared on 28 April at the 50th Annual General Meeting of the Fiji Nursing Association at the Tradewinds Hotel in Lami, on Suva’s outskirts. There was an overwhelming response from the members, with 875 votes cast on all five issues. At the final count, 89 per cent of votes were in favour of taking industrial action – (i) against the 5 per cent salary reduction; (ii) for not honouring the partnership agreement; (iii) for not honouring the MoA signed with the previous Qarase government; (iv) for the breach of the collective agreement on the reduction of the compulsory retirement age from 60 years to 55 years; and, (v) for the imposition of a 12-hour shift for nurses who worked in hospitals.

A trade dispute was lodged on 21 June 2007 with the Ministry of Labour, Industrial Relations and Tourism, through its permanent secretary, Taito Waqa, indicating the cause of the dispute, the results of the secret ballot and the intended date for industrial action (midnight 24 July 2007). As our members worked in essential services, we had to give 28 days notice to the ministry of our intention to take industrial action. The intention of this law, I believe, was to give the relevant ministries enough time to intervene through a dispute committee or mediation process to try to settle the matter amicably.

The FNA then waited for a reply to our notification. We knew that we had followed the rules to the letter, but we received only a reply that the dispute was being analyzed. Even before we knew the result of the secret ballot, the interim Minister for Labour, Industrial Relations and Tourism, Bernadette Rounds Ganilau, had sent me a copy of a letter addressed to the general secretary of the Public Service Association, Rajeshwar Singh, requesting his attendance at a meeting aimed at mediation with the trade unions that were contemplating filing

trade disputes. I immediately sent a reply to her, stating that dialogue was of no use to us because our grievances were already under consideration by our membership through the secret ballot. At that stage, we in the leadership of the FNA were not sure whether or not our members would want to stage industrial

action. I was not happy with the way that the FNA was addressed in the correspondence. It seemed to me that our invitation to the mediation meeting was an afterthought. Furthermore, we did not want to start premature dialogue that might compromise our position. It was the minister herself who wanted to mediate. However, there

are appointed officers in the Ministry of Labour who are trained to do this job. In my opinion, the minister has the last say and is the final decision-maker. For the minister to intervene in person at this early stage would have been a waste of time for us as well as her. Nevertheless, other trade unions decided to meet her for this mediation process. The media later reported that these efforts were not successful.

The countdown for the industrial action started when the trade dispute was lodged. Internally, FNA president Simione Racolo called for an emergency meeting of the FNA national council. At this meeting, we informed the council of the process that was to take place; about the results of the negotiations that we had been having with the PSC; and about the involvement of the permanent secretary for health, Dr Lepani Waqatakirewa. The members were told to prepare their colleagues by updating them weekly on the progress of the talks with the

interim government. As general secretary, I was to be in contact with them if some positive changes seemed likely to materialize. The presidents of all the FNA branches were asked to keep talking to members, encouraging them to keep working normally with the patients. For those who worked in weekly or monthly clinics, they were to be told that, if there were to be industrial action, they were not to come to the health centres or hospitals, but to take a supply of drugs for patients to cover that period. The branch presidents were reminded to choose their picket sites carefully so that they were not on government premises. If picket sites were in public places, the owner of the land was to be approached traditionally. Picket sites in Fijian villages were discouraged, to avoid any appearance of ethnic bias. Ours is a multiracial union, and we did not want to seem dependent on traditional Fijian support. (Sometimes this was unavoidable; in Tavua, for example, the

turaga ni vanua insisted that it was his duty and that of his warriors to protect the nurses.) Other plans included assembly and distribution of the cell-phone numbers of contacts at the branch level because we were not to use the government phones. The FNA national council met to decide on the financial assistance to be given to branches that needed it. In past strikes, we had found it necessary to look after striking members only for two or three days. Judged by our previous strike experiences, we were very optimistic.

A week or two before the 24 July, when the nurses’ strike was scheduled to commence, I continued talks with my counterparts, Agni Deo Singh, the general secretary of Fiji Teachers Union, and Rajeshwar Singh, the general secretary of the Fiji Public Service Association. Together, we tried to negotiate with interim Minister for Public Sector Reform Poseci Bune. This man, I thought, did not know what he was talking about – we found what he was offering absurd because he made no commitment to any movement in the interim government’s position despite being aware that all three of our unions had lodged trade disputes with the Ministry of Labour. He also made it difficult for us to meet him – for example, at one point, giving excuses that he was not in Suva and that we would have to wait until he returned after the weekend.

Meanwhile, our 28 days notice deadline was closing in and we had not made any progress. Rajeshwar Singh again made arrangements with the CPSU to meet the ‘money man’ Mahendra Chaudhry. This arrangement, I believe, was made through Felix Anthony, the general secretary of the Fiji Trade Union Congress (FTUC). By this time, there was a rumour that the FTUC was backing the interim government and that the unions that were affiliated with this organization would not stage any industrial action while the interim government was in power. I do not know how true this was but there were mixed feelings amongst the FTUC affiliates – some of them supported us later on during the strike. We met the interim Minister for Finance at his office on 9 July 2007. This was after the CPSU had met with Poseci Bune earlier on the same day. That afternoon, the CPSU leaders were called to meet with the interim Minister for Finance at the FTUC building to finalize what had been discussed with Rajeshwar Singh at the interim Finance Minister’s office earlier in that day.

During those discussions I was uneasy and sensed that my fellow trade unionists had sold us out because I did not hear any change in the initial offer that the interim government had made to settle our trade dispute. Personally, I wanted to vomit. I couldn’t believe that my colleagues and ‘brother trade unionists’ had embraced defeat by accepting the deal from government without any struggle at all. They had told me that the secret ballots conducted amongst their members had delivered over 90 per cent in favour of industrial action. I could not understand how easily they could change their tune on that day. I prayed that evening as we sat late into the night at the FTUC office, and resolved not to sign any agreement until I had consulted with Simone Racolo and the Suva-based National Council. Some of my colleagues were disappointed by my decision. On 12 June 2007, together with CPSU leaders Rajeshwar Singh and Agni Deo Singh, I met with interim Prime Minister Bainimarama to try to convince him that the policies that they intended to apply to the civil servants would damage the public sector and create a very negative image of the interim government’s leadership, jeopardizing their claims to bring positive change to the country.

Our three unions met more regularly after the nurses’ trade dispute had been lodged, but it became ever clearer that the FPSA and FTA were not committed to strike action or solidarity with the nurses. A week after our dispute was lodged, I met the interim Minister for Commerce, Taito Waradi, and his ministry’s permanent secretary, Mr Yauvoli. Mr Waradi was also acting Minister for the Public Service Commission. He had been informed of our dispute and wanted to talk to me regarding how best our issues could be addressed. I agreed to see him partly because we had been classmates at the Dudley High School in 1970, and because Mr Yauvoli’s wife was a personal friend. At that meeting, I pointed out to both Mr Waradi and Mr Yauvoli the importance to us of the agreement and the MoA. I was afraid that if the interim government did not honour them, it would cause nurses to take industrial action. These were very important agreements for both salaried and wage-earning civil servants. If they were to throw these agreements out, I told them, I was afraid to think of the consequences.

Mr Waradi suggested that perhaps the interim government might shelve or defer the implementation of its planned course of action. I responded that the impact of this would depend on how it was announced to the public and how we in the trade union leadership might explain the interim government’s intentions to our members. I emphasized the fact that the two agreements contained commitments by the government to pay the lost salaries and wages of civil servants who had been in government employment since 2001. In total, the agreements entailed a salary increase of around 27 per cent even without adjustment for the fact that the entire civil service had not received a full increment since 2000. Only about seven per cent of what was contained in the agreement and MoA had been paid by January 2006. Normal increments averaged three per cent for other civil servants. The other important issues were the implementation of the 2003 Mercer Job Evaluation recommendations; the implementation of the intended Performance Management System (PMS) and the job-related allowances; and the need to address the unions’ 2003 log of claims. In the MoA, the issues specific to nurses were: the re-introduction of higher pay for higher professional qualifications and scarce skills; the provision for housing for nurses and medical orderlies or payment of lodging allowance in lieu of housing; and the payment of risk allowance to nurses and medical orderlies who work in high risk areas. These were very important issues for the nurses and had been continually raised at FNA annual general meetings. Even if nurses’ pay remained low, improved working conditions – such as provision of rent-free housing – would discourage many nurses from leaving Fiji.

On 10 July 2007, I called the FNA president and the two Suva-based council members to update them on an offer from interim Finance Minister Mahendra Chaudhry – a restoration of 1 per cent of the proposed 5 per cent pay-cuts in December 2007. I explained my position and I also reminded them about the mandate we had from the members. I wanted to hear their views on the way forward for me as the FNA’s chief negotiator. By this point, I suspected that we were alone in our fight, as the other trade unions had their own issues to think about, and because their mandate from their members was not clear. The president ordered an emergency meeting on 21 July of the full national council so that we could inform them of what had transpired and seek their reaction. The FNA president and I had sought the intervention of the interim Minister for the Public Service Commission as the end of the 28-day notice period drew near. We sat twice with the Permanent Secretary for Health and the Secretary to the PSC on 20 July to try and come to a consensus. At the special national council meeting at the FNA Conference Hall on 21 July 2007, reports from most national council members were presented. Not one of them indicated a negative response to the strike action. While all this was going on, I was involved in a big project with the European Union; it was to start with workshops in Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. I used these opportunities to meet the members and talk to them about what might transpire, and I also gauged their feedback on the strength of resolve in the different branches. One message that we emphasized was ‘explain to your husband/wife and family members why we have to take strike action, so that they will support

you’. We did not know how long the scheduled strike would last, but, because there would be no pay for a number of days, we needed their understanding and cooperation. We had very able and committed national council members representing the 20 FNA branches, and they were very aware of the difficulties that we would face by making a stand on our own. Our CPSU team had broken up and I respected the decisions that my colleagues had taken. I had to brace myself for the outcome of the FNA emergency meeting of 21 July 2007.

After that, there was no turning back. The president and I had received warnings, and even threats, that we couldn’t back out at that stage as the response from the branch representatives was overwhelming. We knew that, because many of our members were married to members of the security forces, they might face severe pressure to back down; but the word from many of them was ‘they became nurses first and got married later’. Many of these brave women and men came out on strike when the clock struck midnight on 24 July 2007. The media and members of the security forces continued to hound me and the FNA president around the clock for comments and explanations. Other members of the national council were also pestered by members of the security forces near their workplace. However, we handled this professionally. There were two incidents of violence reported to us involving members being manhandled by their spouses; we allowed these members to go back to work for their own safety.

On the first day, more than 1,000 nurses were reported to be at the 20 picket sites. Others joined in on the second and third days. Even some non-members joined in and, as they did so, filled in FNA membership forms at the different strike sites around the country. On the second day, we called upon interim Prime Minister Bainimarama to intervene. He refused. Instead, he said the strike was a ploy to bring down his government, and that the stand-off with the unions could have the effect of deferring the elections planned for 2009. He claimed his government did not have the money to restore the five per cent pay cut. But we wanted proof that the government had no money – there seemed to be plenty available for government ministers to take overseas trips at the taxpayers’ expense. In the first few days of the strike it looked as if we might get somewhere; interim

Minister for Labour Bernadette Rounds Ganilau kept promising that concessions would be made and that the dispute could be settled. She admitted that our strike was legal, but she was too intimidated by the interim prime minister to take action and make a decision in our favour, and so she kept delaying.

Whatever authority she had over industrial disputes was taken away from her by Bainimarama, who was determined that our strike should fail. Our initial request to government had been that they should restore the one per cent immediately, restore two per cent in December 2007 and the remaining two per cent in 2008, but once the strike began we went back to demanding the full five per cent. In the end, Bainimarama offered us one per cent, with further discussions to take place over the remaining four per cent. We had been down that road too many times before and we were not fooled. What that meant was nothing beyond one per cent. The truth was that, going back to 2003, we were actually owed a pay increase of 27 per cent. Talking to the media, I pointed out that there was a vast imbalance between the work we did and the amount we were paid, and I wanted to know why nurses always faced pay cuts when a military coup took place.

Mahendhra Chaudry blamed me, rather than the government, for the plight of the nurses, and said we should have sorted all this out with the Qarase government rather than raising the issue when finances were in a critical state. Fiji Human Rights Commission director Shaista Shameem said the right to life of patients, sick people and the elderly was more important than the right to strike, to which I replied that these were not normal times and that our hands had been forced by poor working conditions and low pay. Ultimately, I said, the right to life was the responsibility of the government, not of the nurses. The Methodist Church, possibly Fiji’s largest and most important institution outside government, refused to help the interim government when asked for assistance. Church president Reverend Laisiasa Ratabacaca said the government

was responsible for the situation and that the church would not interfere.

We had to tighten security at our headquarters in MacGregor Road because we thought the strike might attract people who would use our struggle for their own political purposes. Our concern, as I kept telling the media, related purely to nurses’ issues, and the interim government, which was in charge of the country, should not be surprised if all sorts of problems arose. ‘Every coup’, I pointed out, ‘sets a country back 10 years and I hope the prime minister doesn’t forget it’. On 2 August I told the media ‘We have reached day nine and now there is no turning back. Our members have indicated there is nothing stopping them from carrying on in order to get their five per cent back’. I called on the nurses who were still working to join the strike: ‘As long as some nurses remain in hospitals’, I said, ‘this fight will go on. If all members come out and sit, then we will prove to the interim government that nurses are vital in order to have the hospitals functioning.

Nurses must unite and take industrial action’.

By 8 August, however, we realized that the interim government was willing to let Fiji’s hospitals and health system collapse rather than yield to our demands. We had held together for more than two weeks. We had strengthened each other at the picket sites with chain prayers and singing, and people had helped us, but we could not hold out indefinitely because we had no savings. Fiji’s nurses are not prosperous. It was impossible for them to accumulate sufficient savings to survive through a long-running strike.