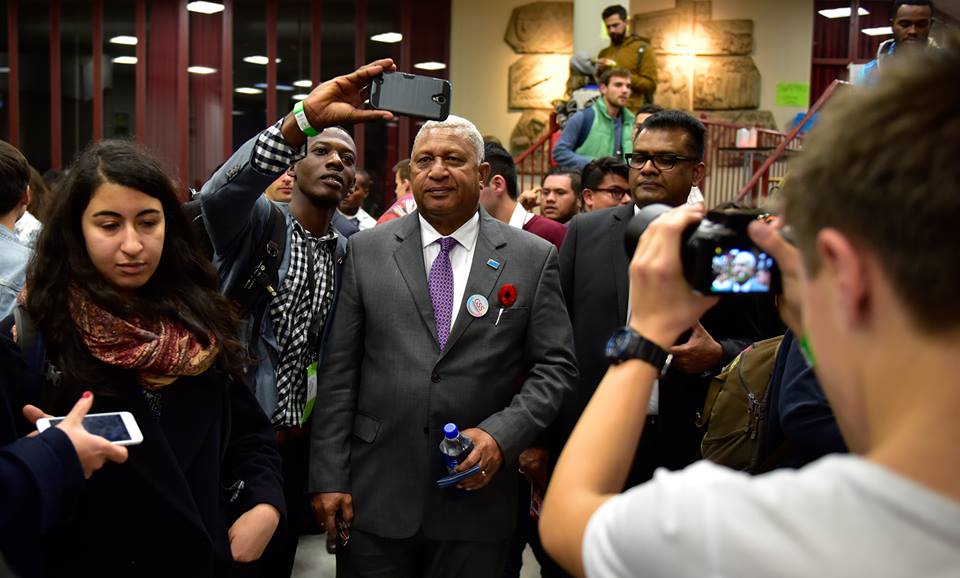

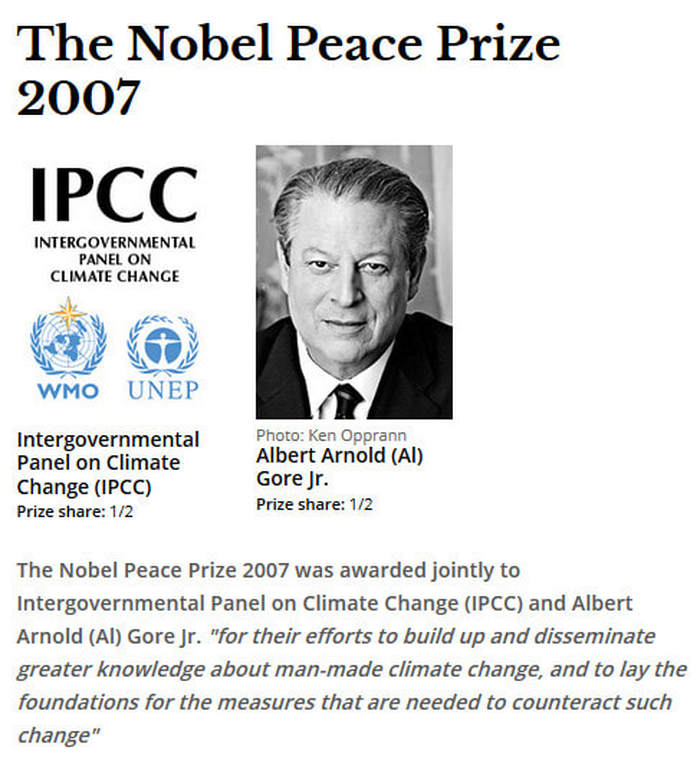

There are whispers in the corridors of the Bonn conference that COP 23 and its President Frank Bainimarama could be nominated for the 2018 NOBEL PEACE PRIZE. In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and former US Vice President Al Gore shared, in two equal parts, the Nobel Peace Prize. The IPCC was established in 1988 by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). In 2018 the IPCC will be celebrating its 30th anniversary

Prime Minister Bainimarama closed the 13th Conference of Youth (COY13) in Bonn, Germany today. More than 1000 youth contributors from 114 countries, including Fiji, are in Bonn in the lead up to COP23 to discuss climate change in a programme comprised of 225 single events. In praising the youths for their determination to see climate action making real lasting impacts, Prime Minister Bainimarama also called on them to work with his presidency to realise this. Source: Fiji Government Facebook

| The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2007 is to be shared, in two equal parts, between the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and Albert Arnold (Al) Gore Jr. for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change. Indications of changes in the earth's future climate must be treated with the utmost seriousness, and with the precautionary principle uppermost in our minds. Extensive climate changes may alter and threaten the living conditions of much of mankind. They may induce large-scale migration and lead to greater competition for the earth's resources. Such changes will place particularly heavy burdens on the world's most vulnerable countries. There may be increased danger of violent conflicts and wars, within and between states. |

Through the scientific reports it has issued over the past two decades, the IPCC has created an ever-broader informed consensus about the connection between human activities and global warming. Thousands of scientists and officials from over one hundred countries have collaborated to achieve greater certainty as to the scale of the warming. Whereas in the 1980s global warming seemed to be merely an interesting hypothesis, the 1990s produced firmer evidence in its support. In the last few years, the connections have become even clearer and the consequences still more apparent.

Al Gore has for a long time been one of the world's leading environmentalist politicians. He became aware at an early stage of the climatic challenges the world is facing. His strong commitment, reflected in political activity, lectures, films and books, has strengthened the struggle against climate change. He is probably the single individual who has done most to create greater worldwide understanding of the measures that need to be adopted.

By awarding the Nobel Peace Prize for 2007 to the IPCC and Al Gore, the Norwegian Nobel Committee is seeking to contribute to a sharper focus on the processes and decisions that appear to be necessary to protect the world’s future climate, and thereby to reduce the threat to the security of mankind. Action is necessary now, before climate change moves beyond man’s control. Oslo, 12 October 2007

Al Gore has for a long time been one of the world's leading environmentalist politicians. He became aware at an early stage of the climatic challenges the world is facing. His strong commitment, reflected in political activity, lectures, films and books, has strengthened the struggle against climate change. He is probably the single individual who has done most to create greater worldwide understanding of the measures that need to be adopted.

By awarding the Nobel Peace Prize for 2007 to the IPCC and Al Gore, the Norwegian Nobel Committee is seeking to contribute to a sharper focus on the processes and decisions that appear to be necessary to protect the world’s future climate, and thereby to reduce the threat to the security of mankind. Action is necessary now, before climate change moves beyond man’s control. Oslo, 12 October 2007

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/nov/03/climate-change-report-us-government-contradicts-trump

The Nobel Peace Prize is the most contentious of Alfred Nobel's prizes. The following extract from our Founding Editor-in-Chief VICTOR LAL's forthcoming book TOWARDS A WORLD WITHOUT WAR: Andrew Carnegie, The Peacemakers, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the Nobel Peace Prize, 1901-1951 (which Lal researched and wrote while holding a Guest Nobel Fellowship at the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo) gives us a glimpse of the history and controversy of

the Nobel Peace Prize:

THe Nobel Peace Prize, created out of the 1895 will of the dynamite king Alfred Nobel, has been routinely described as the greatest honour that a man get in this world. The Oxford Dictionary of Twentieth Century World History states that the Nobel Peace Prize is ‘the world’s most prestigious prize awarded for the preservation of peace’. In 2001, the Prize celebrated its centennial. The Norwegian Nobel Committee decided to award the last Nobel Peace Prize for the 20th Century, in two equal portions, to the United Nations (U.N.) and to its Secretary-General, Kofi Anan. The Prize was given out in the Norwegian capital Oslo on 10 December 2001, three months after the most horrific terrorist attack of September 11 on the United States, which houses the UN.

The Nobel Committee had announced in October that it wanted ‘in its centenary year to proclaim that the only negotiable route to global peace and cooperation goes by way of the United Nations’, although the Committee was acutely aware that UN had provided the legal basis for the immediate military response to the attacks. On 12 September, the day after the Twin Tower attacks, both the UN Security Council and General Assembly had condemned them. In its resolution 1368 the Security Council defined them as ‘a threat to international peace and security’. This authorized the military response of the United States, since Article 51 of the UN Charter declares that any country has the right to defend itself if attacked until the Security Council takes measures to ensure peace and security.

Since its inception in 1901, several men, and a few women and organisations, have become Nobel laureates. There have been the ‘also ran’ ones, popularly referred to as the ‘Nobel Peace Prize Nominees’. In the first half of the twentieth century, between 1901 and 1951, some of the nominees included the likes of Adolf Hitler of Germany and Joseph Stalin of the former Soviet Union, ‘the twin demons of the twentieth century’, and also Hitler’s comic side-kick and fascist dictator Benito Mussolini of Italy.

Imperial monarchs like Wilhelm 11 of Germany, Franz Josef of Austria and Hungary, Czar Nikolai II of Russia, Alfonso XIII of Spain, Albert 1 of Belgium, and Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, joined them on the peace list. So did the ‘Men of God’, the Popes in Rome: Benedict XV, Pius XI, and Pius XII, the last described frequently as ‘Hitler’s Pope’ for failing to save the Jews from Mussolini’s Italy, and one British historian describing the pontiff as ‘arguably the most insidiously evil churchman in modern history who did more than fail to speak out against Nazi crimes’.

The Presidents and Prime Ministers were not to be left behind in their rush for Nobel’s peace prize. Among those sharing nomination with Hitler in 1939 was his co-signatory to the infamous Munich Pact, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Other British Prime Ministers who made it on to the list included Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George, Clement Atlee, and Ramsay MacDonald. Alexander Papanastassiou of Greece, Édouard Herriot and Pierre Laval of France, General Jan Smuts of South Africa, and Francesco Saverio Nitti of Italy became the ‘also ran’ prime ministers. Tómaš Masaryk and Edvard Beneš (that ‘little swine’ as Lloyd George described him) of Czechoslovakia, and Count Albert Apponyni of Hungary, also found their names on to the Nobel Prize Nominees List.

Laval, together with British Foreign Secretary Samuel Hoare, had developed the so-called Hoare-Laval Plan for the partition of Ethiopia between Italy and Ethiopia after Mussolini had invaded Abyssinia causing Emperor Selassie to flee to Great Britain. In 1936 both men were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1945, as leader of the Vichy government during the Second World War, Laval was convicted and executed for treason. Mussolini, whose son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano (executed by the Germans) had described the Italian dictator in a letter intended for Winston Churchill as ‘Hitler’s tragic and vile puppet’, was also executed and his mutilated body was hung by his feet from the girders of a garage roof in the Piazzale Loreto. Two days later, Adolf Hitler committed suicide in a Berlin bunker.

Meanwhile, from across the Atlantic came nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize in support of the Roosevelts: Theodore, Franklin, and Elena Roosevelt. The United States presidents included Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman, Warren Harding, William Howard Taft, and Herbert Hoover. The US Secretary of States included Elihu Root, Charles Hughes, Frank Kellog, and Cordell Hull. Their counterparts in Europe included Milovan Milovanovitch of Yugoslavia, who was nominated in 1910 for his efforts to prevent the Serbian-Austrian conflict from turning into war. Similarly, Sir Edward Grey (Lord Grey of Falloden) was put forward for the Treaty of London of 1915, by which Italy joined the Allies, in the First World War. Foreign Ministers Gustav Stresemann of Germany, Astride Briand of France, and Austen Chamberlain of Great Britain later shared the prize with Kellog for signing the Lorcano Pact that guaranteed peace around Germany’s frontier, and the Briand-Kellog Pact, which ‘outlawed’ war. Stresemann’s colleague Hans Luther, the former Chancellor and German Foreign Minister, however missed out.

Many peacemakers at the Paris Peace Conference 1919, which saw the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, were also put forward as deserving candidates. They included the Aga Khan, who had strenuously fought on behalf of Turkey in the Treaty of Sèvres, to the economist John Maynard Kenyes, who had resigned in disgust at the final reparations settlement, describing it as ‘Carthaginian Peace’ in his The Economic Consequences of Peace, to Lord Cecil of Chelwood and the Italian Vittorio Scialoja, for their roles in the creation of the League of Nations.

Even some military generals found themselves among their peace adversaries. In 1949 the American Major General Frank Ross McCoy was nominated for democratising Japan after the Second World War. From Germany came the nomination of Baron Paul von Schoenaich, a former army officer and president of the German Peace Association, who had become an opponent of war and advocated democracy, pacifism, and radical disarmament. And from Britain came the name of Brigadier-General and jurist John Hartman Morgan, who was nominated for his efforts to disarm Germany between 1919 and 1923, and for his plans after the World War Two. And General Dwight Eisenhower, later President but who in 1944 was the Supreme Commander of the troops invading France.

Moreover, while Hitler’s name was to be eternally linked to infamy, genocide, and mass murder, some of his countrymen could still be considered by their international admirers as the peacemakers: the 1936 Nobel laureate Carl von Ossietzky, the journalist and pacifist who died in Hitler’s concentration camp, pacifists like Ludwig Quidde, and the eugenicist and biologist Alfred Ploetz, the founder of racial hygiene in Germany, who was nominated for warning against biological consequences that inflicted on human reproduction.

Although men of war and men of peace dominated the world, a few courageous women like Jane Addams, Emily Balch, and Baroness Bertha von Suttner found their voices heard in the deliberations of the Nobel Committee. All three were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize before the first half of the twentieth century. If politicians, presidents, and prime ministers grabbed international headlines, there were scores of other soldiers of peace, including Lord Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boys Scout, who made it to the Nobel Peace Prize Nominees list. Among them was the most famous and richest of them all – Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish born American steel magnate.

This book, accordingly, focuses on Carnegie, his peace activities, the founding of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and his failure to receive Alfred Nobel’s peace prize. Carnegie was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1908, 1911, and 1913, and yet the story has never as yet been related at all. Nor has any considerable attempt been made as yet to explore his peace activities, the role of CEIP, which he founded to promote international peace and harmony, and his relationship with the Nobel Peace laureates.

The eminent historian Eric Hobsbawm forcefully argued in his classic The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 that preparations for war became vastly more expensive, especially as states competed to keep ahead of, or at least to avoid falling behind, each other. This arms race began in a particularly modest way in the later 1880s, and accelerated in the new century, particularly in the last ten years before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. One consequence, he continued, of such vast expenditures was they required either higher taxes, or inflationary borrowing or both. But an equally obvious, though often overlooked consequence, was that they increasingly made death for various fatherlands a by-product of large-scale industry.

Hobsbawn however pointed out that two men in particular, ‘Alfred Nobel and Andrew Carnegie, two capitalists who knew what had made them millionaires in explosives and steel respectively, tried to compensate by devoting part of their wealth to the cause of peace’. In this, Hobsbawm concludes, ‘they were untypical’. Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, whose main objective was the elimination of war in international relations, created the Peace Prize and Carnegie, the steel magnate, founded the Endowment for International Peace with the professed aim ‘to hasten the abolition of international war, the foulest blot upon our civilisation’. He had also concluded that war was wasteful and disruptive to international commerce.

And yet the 21st Century is already engulfed in wars, ethnic conflicts, and the increase in nuclear arms race. Governments, organisations, statesmen, church leaders, and ordinary and men and women are therefore once again being challenged to find ways and means to organize peace. In our never ending quest and hope for a peaceful 21st Century, it would be worth recalling two extraordinary but controversial advocates of peace - Alfred Nobel and Andrew Carnegie - who provided the opportunity and recognition to those who believed, and continue to believe, in peace, justice, and a stable world order. After all, the 20th Century was one of the bloodiest that had also challenged and tested the will and power of those who never lost faith in working towards a world without war. If the last century was the century of wars, it was also the century of celebrations and anniversaries in the organization for peace.

The year 1996, especially, is of significance, in the context of this study. On 10 December 1996 it was the 100th death anniversary of Alfred Nobel, the Swedish industrialist, who wrote his will on 27 November 1895 in the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, establishing the Nobel Peace Prize, hailed as the ‘greatest honour a man can receive in this world’.

The year 1995, and onward, was also the years of anniversaries. For example, 1995 marked the ninetieth anniversary of the formal opening of The Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo established ‘to follow the development of international relations, especially the work for their peaceful adjustment, and thereby to guide the [Nobel] Committee in the matter of the award of the [Nobel] Peace Prize’. The Nobel Committee building near the gardens of the Royal Palace in Oslo, according to one veteran chronicler of the Nobel Peace Prize, Irwin Abrams, ‘is a dignified structure, but modest indeed compared to the grandiose Palace of Peace that Andrew Carnegie built a few years later in The Hague for the Permanent Court of Arbitration’. Today, the Peace Palace is host to The International Court of Justice, the principal judicial organ of the United Nations, The Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague Academy of International Law, and the Peace Palace Library.

That year also marked the one hundred and sixtieth anniversary of the birth of Carnegie, who was born on 25 November 1835, into a family of disfranchised craftsman and Chartists, in the ancient Scottish town of Dunfermline. Moreover, 14 December 1995 was the eighty-fifth anniversary of the deed of gift by Carnegie to his Trustees establishing the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace [CEIP]. Further, the year 1997 also marked the fiftieth anniversary of the CEIP's failed attempt to win the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize.

The Austrian peace activist and Alfred Nobel’s former secretary, Countess Bertha von Suttner, for example, was also an acquaintance of Carnegie. She became the first woman in 1905 to become a Nobel laureate. Generally regarded as the one who stimulated both Nobel and Carnegie’s interests in peace, the two men, independently of one another, rewarded her during her last years: she used Nobel’s 1905 peace prize money to support herself and in the last years the Countess received a pension from Carnegie.

The book moreover recounts how Nobel and Carnegie reached the same goals: renunciation of war and the advocacy of international peace, arbitration, and disarmament. Nobel established the Peace Prize and Carnegie gave away his fortune in the pursuit of peace. Carnegie hoped that men would some day view ‘those machines made expressly for the destruction of their fellow men only in the Museum, as relics of a barbarous age’. Between 1904 and 1919, as one of Carnegie’s biographers points out, he gave more than £25,250 to fund a ‘Temple of Peace’ and major foundations concerned with peace and ‘the heroes of peace’.

Nobel, on the other hand, while establishing the peace prize, ‘gave the world thirty years to found a system of peace or else revert to barbarism, but he cherished the hope that within that time the enlightening effects of scientific progress would rid the earth of war’. Briefly, in his will of 1895, Alfred Nobel wanted exceptional people to be honoured for their significant contributions in the fields of physics, chemistry, medicine, literature and work for peace. He stipulated that Swedish institutions should award the scientific prizes and the prize for literature. The award for the peace prize was left to the Norwegian Nobel Committee, appointed by the Norwegian Storting or Parliament, to award an annual prize to people and institutions ‘who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses’.

First awarded in 1901, the peace prize went to Jean Henri Dunant, the Swiss founder of Red Cross and originator of the Geneva Convention, and to Frederic Passy, the doyen of the pre-1914 peace movement and founder and president of the first French peace society. In subsequent years there have also been some spectacular omissions for the Nobel Peace Prize: Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest proponent of non-violence, and the Russian pacifist Count Leo Tolstoy, the author of the magisterial War and Peace. Many others generally considered as ‘advocates of peace’ failed to make it on to the winner’s list.

This book does not claim that Carnegie deserved Nobel’s peace prize but explores Carnegie’s advocacy for international arbitration, justice, world peace, and the abolition of war. It is, however, anchored in his unsuccessful attempts to win the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize. But the book is more: it follows the activities of statesmen and peace advocates at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 who drew up the Treaty of Versailles, and created the League of Nations that was to promote international co-operation and to achieve international peace and security. It examines why one of those at the Conference, President Woodrow Wilson, was rewarded with a Nobel Peace Prize for his role in the founding of the League while others like British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, was overlooked.

And so was Carnegie, the most active peace campaigner, who embodied everything the Nobel Peace Prize demanded and yet was passed over three times during his lifetime. He had once written to Theodore Roosevelt, who had become the first statesmen to receive the prize in 1906 for mediating the Russo-Japanese War: ‘The man who passes into history as the chief agent in banishing war or even lessening war, the great evil of his day, is to stand for all time among the foremost benefactors. Only as the strongest apostle of peace of your day, you can take permanent rank with the very few immortals whom the tooth of time is not to gnaw into oblivion.’

In reminding Roosevelt, Carnegie was portraying something of his own life and character as an active peace crusader. In general, although Carnegie never became a Nobel laureate, in spirit and action he did share the characteristics of Alfred Nobel who has been described as ‘the pessimist with the optimistic program, the realist whose efforts were based on idealistic premises’.

The pages that follow tell the story of two of the world’s remarkable millionaire pacifists but within the framework of war and peace, and the Nobel Peace Prize which celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2001. The book confines itself to the first half of the twentieth century, for it was one of the bloodiest that tested the will and staying power of the peacemakers, among them Carnegie, the millionaire pacifist. The struggle is not, of course, over yet. The book begins with the inventor of dynamite Alfred Nobel, who never conceded that his inventions were incompatible with peace, and ends with Andrew Carnegie, to whom Nobel’s Peace Prize eluded him.

Moreover, can we look back at the past to find solutions to the present, for not a day passes without the outbreak of a conflict or the failure of a peace process that is not reported in the world press.

Are the peacemakers of the past a reference point for the present, or the future?

The Nobel Committee had announced in October that it wanted ‘in its centenary year to proclaim that the only negotiable route to global peace and cooperation goes by way of the United Nations’, although the Committee was acutely aware that UN had provided the legal basis for the immediate military response to the attacks. On 12 September, the day after the Twin Tower attacks, both the UN Security Council and General Assembly had condemned them. In its resolution 1368 the Security Council defined them as ‘a threat to international peace and security’. This authorized the military response of the United States, since Article 51 of the UN Charter declares that any country has the right to defend itself if attacked until the Security Council takes measures to ensure peace and security.

Since its inception in 1901, several men, and a few women and organisations, have become Nobel laureates. There have been the ‘also ran’ ones, popularly referred to as the ‘Nobel Peace Prize Nominees’. In the first half of the twentieth century, between 1901 and 1951, some of the nominees included the likes of Adolf Hitler of Germany and Joseph Stalin of the former Soviet Union, ‘the twin demons of the twentieth century’, and also Hitler’s comic side-kick and fascist dictator Benito Mussolini of Italy.

Imperial monarchs like Wilhelm 11 of Germany, Franz Josef of Austria and Hungary, Czar Nikolai II of Russia, Alfonso XIII of Spain, Albert 1 of Belgium, and Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, joined them on the peace list. So did the ‘Men of God’, the Popes in Rome: Benedict XV, Pius XI, and Pius XII, the last described frequently as ‘Hitler’s Pope’ for failing to save the Jews from Mussolini’s Italy, and one British historian describing the pontiff as ‘arguably the most insidiously evil churchman in modern history who did more than fail to speak out against Nazi crimes’.

The Presidents and Prime Ministers were not to be left behind in their rush for Nobel’s peace prize. Among those sharing nomination with Hitler in 1939 was his co-signatory to the infamous Munich Pact, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Other British Prime Ministers who made it on to the list included Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George, Clement Atlee, and Ramsay MacDonald. Alexander Papanastassiou of Greece, Édouard Herriot and Pierre Laval of France, General Jan Smuts of South Africa, and Francesco Saverio Nitti of Italy became the ‘also ran’ prime ministers. Tómaš Masaryk and Edvard Beneš (that ‘little swine’ as Lloyd George described him) of Czechoslovakia, and Count Albert Apponyni of Hungary, also found their names on to the Nobel Prize Nominees List.

Laval, together with British Foreign Secretary Samuel Hoare, had developed the so-called Hoare-Laval Plan for the partition of Ethiopia between Italy and Ethiopia after Mussolini had invaded Abyssinia causing Emperor Selassie to flee to Great Britain. In 1936 both men were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1945, as leader of the Vichy government during the Second World War, Laval was convicted and executed for treason. Mussolini, whose son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano (executed by the Germans) had described the Italian dictator in a letter intended for Winston Churchill as ‘Hitler’s tragic and vile puppet’, was also executed and his mutilated body was hung by his feet from the girders of a garage roof in the Piazzale Loreto. Two days later, Adolf Hitler committed suicide in a Berlin bunker.

Meanwhile, from across the Atlantic came nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize in support of the Roosevelts: Theodore, Franklin, and Elena Roosevelt. The United States presidents included Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman, Warren Harding, William Howard Taft, and Herbert Hoover. The US Secretary of States included Elihu Root, Charles Hughes, Frank Kellog, and Cordell Hull. Their counterparts in Europe included Milovan Milovanovitch of Yugoslavia, who was nominated in 1910 for his efforts to prevent the Serbian-Austrian conflict from turning into war. Similarly, Sir Edward Grey (Lord Grey of Falloden) was put forward for the Treaty of London of 1915, by which Italy joined the Allies, in the First World War. Foreign Ministers Gustav Stresemann of Germany, Astride Briand of France, and Austen Chamberlain of Great Britain later shared the prize with Kellog for signing the Lorcano Pact that guaranteed peace around Germany’s frontier, and the Briand-Kellog Pact, which ‘outlawed’ war. Stresemann’s colleague Hans Luther, the former Chancellor and German Foreign Minister, however missed out.

Many peacemakers at the Paris Peace Conference 1919, which saw the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, were also put forward as deserving candidates. They included the Aga Khan, who had strenuously fought on behalf of Turkey in the Treaty of Sèvres, to the economist John Maynard Kenyes, who had resigned in disgust at the final reparations settlement, describing it as ‘Carthaginian Peace’ in his The Economic Consequences of Peace, to Lord Cecil of Chelwood and the Italian Vittorio Scialoja, for their roles in the creation of the League of Nations.

Even some military generals found themselves among their peace adversaries. In 1949 the American Major General Frank Ross McCoy was nominated for democratising Japan after the Second World War. From Germany came the nomination of Baron Paul von Schoenaich, a former army officer and president of the German Peace Association, who had become an opponent of war and advocated democracy, pacifism, and radical disarmament. And from Britain came the name of Brigadier-General and jurist John Hartman Morgan, who was nominated for his efforts to disarm Germany between 1919 and 1923, and for his plans after the World War Two. And General Dwight Eisenhower, later President but who in 1944 was the Supreme Commander of the troops invading France.

Moreover, while Hitler’s name was to be eternally linked to infamy, genocide, and mass murder, some of his countrymen could still be considered by their international admirers as the peacemakers: the 1936 Nobel laureate Carl von Ossietzky, the journalist and pacifist who died in Hitler’s concentration camp, pacifists like Ludwig Quidde, and the eugenicist and biologist Alfred Ploetz, the founder of racial hygiene in Germany, who was nominated for warning against biological consequences that inflicted on human reproduction.

Although men of war and men of peace dominated the world, a few courageous women like Jane Addams, Emily Balch, and Baroness Bertha von Suttner found their voices heard in the deliberations of the Nobel Committee. All three were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize before the first half of the twentieth century. If politicians, presidents, and prime ministers grabbed international headlines, there were scores of other soldiers of peace, including Lord Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boys Scout, who made it to the Nobel Peace Prize Nominees list. Among them was the most famous and richest of them all – Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish born American steel magnate.

This book, accordingly, focuses on Carnegie, his peace activities, the founding of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and his failure to receive Alfred Nobel’s peace prize. Carnegie was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1908, 1911, and 1913, and yet the story has never as yet been related at all. Nor has any considerable attempt been made as yet to explore his peace activities, the role of CEIP, which he founded to promote international peace and harmony, and his relationship with the Nobel Peace laureates.

The eminent historian Eric Hobsbawm forcefully argued in his classic The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 that preparations for war became vastly more expensive, especially as states competed to keep ahead of, or at least to avoid falling behind, each other. This arms race began in a particularly modest way in the later 1880s, and accelerated in the new century, particularly in the last ten years before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. One consequence, he continued, of such vast expenditures was they required either higher taxes, or inflationary borrowing or both. But an equally obvious, though often overlooked consequence, was that they increasingly made death for various fatherlands a by-product of large-scale industry.

Hobsbawn however pointed out that two men in particular, ‘Alfred Nobel and Andrew Carnegie, two capitalists who knew what had made them millionaires in explosives and steel respectively, tried to compensate by devoting part of their wealth to the cause of peace’. In this, Hobsbawm concludes, ‘they were untypical’. Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, whose main objective was the elimination of war in international relations, created the Peace Prize and Carnegie, the steel magnate, founded the Endowment for International Peace with the professed aim ‘to hasten the abolition of international war, the foulest blot upon our civilisation’. He had also concluded that war was wasteful and disruptive to international commerce.

And yet the 21st Century is already engulfed in wars, ethnic conflicts, and the increase in nuclear arms race. Governments, organisations, statesmen, church leaders, and ordinary and men and women are therefore once again being challenged to find ways and means to organize peace. In our never ending quest and hope for a peaceful 21st Century, it would be worth recalling two extraordinary but controversial advocates of peace - Alfred Nobel and Andrew Carnegie - who provided the opportunity and recognition to those who believed, and continue to believe, in peace, justice, and a stable world order. After all, the 20th Century was one of the bloodiest that had also challenged and tested the will and power of those who never lost faith in working towards a world without war. If the last century was the century of wars, it was also the century of celebrations and anniversaries in the organization for peace.

The year 1996, especially, is of significance, in the context of this study. On 10 December 1996 it was the 100th death anniversary of Alfred Nobel, the Swedish industrialist, who wrote his will on 27 November 1895 in the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, establishing the Nobel Peace Prize, hailed as the ‘greatest honour a man can receive in this world’.

The year 1995, and onward, was also the years of anniversaries. For example, 1995 marked the ninetieth anniversary of the formal opening of The Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo established ‘to follow the development of international relations, especially the work for their peaceful adjustment, and thereby to guide the [Nobel] Committee in the matter of the award of the [Nobel] Peace Prize’. The Nobel Committee building near the gardens of the Royal Palace in Oslo, according to one veteran chronicler of the Nobel Peace Prize, Irwin Abrams, ‘is a dignified structure, but modest indeed compared to the grandiose Palace of Peace that Andrew Carnegie built a few years later in The Hague for the Permanent Court of Arbitration’. Today, the Peace Palace is host to The International Court of Justice, the principal judicial organ of the United Nations, The Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague Academy of International Law, and the Peace Palace Library.

That year also marked the one hundred and sixtieth anniversary of the birth of Carnegie, who was born on 25 November 1835, into a family of disfranchised craftsman and Chartists, in the ancient Scottish town of Dunfermline. Moreover, 14 December 1995 was the eighty-fifth anniversary of the deed of gift by Carnegie to his Trustees establishing the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace [CEIP]. Further, the year 1997 also marked the fiftieth anniversary of the CEIP's failed attempt to win the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize.

The Austrian peace activist and Alfred Nobel’s former secretary, Countess Bertha von Suttner, for example, was also an acquaintance of Carnegie. She became the first woman in 1905 to become a Nobel laureate. Generally regarded as the one who stimulated both Nobel and Carnegie’s interests in peace, the two men, independently of one another, rewarded her during her last years: she used Nobel’s 1905 peace prize money to support herself and in the last years the Countess received a pension from Carnegie.

The book moreover recounts how Nobel and Carnegie reached the same goals: renunciation of war and the advocacy of international peace, arbitration, and disarmament. Nobel established the Peace Prize and Carnegie gave away his fortune in the pursuit of peace. Carnegie hoped that men would some day view ‘those machines made expressly for the destruction of their fellow men only in the Museum, as relics of a barbarous age’. Between 1904 and 1919, as one of Carnegie’s biographers points out, he gave more than £25,250 to fund a ‘Temple of Peace’ and major foundations concerned with peace and ‘the heroes of peace’.

Nobel, on the other hand, while establishing the peace prize, ‘gave the world thirty years to found a system of peace or else revert to barbarism, but he cherished the hope that within that time the enlightening effects of scientific progress would rid the earth of war’. Briefly, in his will of 1895, Alfred Nobel wanted exceptional people to be honoured for their significant contributions in the fields of physics, chemistry, medicine, literature and work for peace. He stipulated that Swedish institutions should award the scientific prizes and the prize for literature. The award for the peace prize was left to the Norwegian Nobel Committee, appointed by the Norwegian Storting or Parliament, to award an annual prize to people and institutions ‘who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses’.

First awarded in 1901, the peace prize went to Jean Henri Dunant, the Swiss founder of Red Cross and originator of the Geneva Convention, and to Frederic Passy, the doyen of the pre-1914 peace movement and founder and president of the first French peace society. In subsequent years there have also been some spectacular omissions for the Nobel Peace Prize: Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest proponent of non-violence, and the Russian pacifist Count Leo Tolstoy, the author of the magisterial War and Peace. Many others generally considered as ‘advocates of peace’ failed to make it on to the winner’s list.

This book does not claim that Carnegie deserved Nobel’s peace prize but explores Carnegie’s advocacy for international arbitration, justice, world peace, and the abolition of war. It is, however, anchored in his unsuccessful attempts to win the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize. But the book is more: it follows the activities of statesmen and peace advocates at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 who drew up the Treaty of Versailles, and created the League of Nations that was to promote international co-operation and to achieve international peace and security. It examines why one of those at the Conference, President Woodrow Wilson, was rewarded with a Nobel Peace Prize for his role in the founding of the League while others like British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, was overlooked.

And so was Carnegie, the most active peace campaigner, who embodied everything the Nobel Peace Prize demanded and yet was passed over three times during his lifetime. He had once written to Theodore Roosevelt, who had become the first statesmen to receive the prize in 1906 for mediating the Russo-Japanese War: ‘The man who passes into history as the chief agent in banishing war or even lessening war, the great evil of his day, is to stand for all time among the foremost benefactors. Only as the strongest apostle of peace of your day, you can take permanent rank with the very few immortals whom the tooth of time is not to gnaw into oblivion.’

In reminding Roosevelt, Carnegie was portraying something of his own life and character as an active peace crusader. In general, although Carnegie never became a Nobel laureate, in spirit and action he did share the characteristics of Alfred Nobel who has been described as ‘the pessimist with the optimistic program, the realist whose efforts were based on idealistic premises’.

The pages that follow tell the story of two of the world’s remarkable millionaire pacifists but within the framework of war and peace, and the Nobel Peace Prize which celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2001. The book confines itself to the first half of the twentieth century, for it was one of the bloodiest that tested the will and staying power of the peacemakers, among them Carnegie, the millionaire pacifist. The struggle is not, of course, over yet. The book begins with the inventor of dynamite Alfred Nobel, who never conceded that his inventions were incompatible with peace, and ends with Andrew Carnegie, to whom Nobel’s Peace Prize eluded him.

Moreover, can we look back at the past to find solutions to the present, for not a day passes without the outbreak of a conflict or the failure of a peace process that is not reported in the world press.

Are the peacemakers of the past a reference point for the present, or the future?

"The Norwegian Nobel Committee rarely raises its voice. Our style is largely sober. But it is a long time since the committee was concerned with such fundamental questions as this year. Desmond Tutu, Peace Prize Laureate in 1984, put it as follows in Tromsø's Arctic Cathedral in connection with World Environment Day on the 5th of June: "To ignore the challenge of global warming may be criminal. It certainly is disobeying God. It is sin. The future of our fragile, beautiful planet is in our hands. We are stewards of God's creation". We congratulate the IPCC and Al Gore on receiving this year's Peace Prize. We thank you for what you have done for mother earth, and wish you further success in a task that is so vital to us all. Action is needed now. Climate changes are already moving beyond human control."

The Norwegian Nobel Committee, 2007

Qualified Nominators for the Nobel Peace Prize

Revised September 2016 by Norwegian Nobel Committe

According to the statutes of the Nobel Foundation, a nomination is considered valid if it is submitted by a person who falls within one of the following categories:

• Members of national assemblies and national governments (cabinet members/ministers) of sovereign states as well as current heads of states

• Members of The International Court of Justice in The Hague and The Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague

• Members of Institut de Droit International

• University professors, professors emerita and associate professors of history, social sciences, law, philosophy, theology, and religion; university rectors and university directors (or their equivalents); directors of peace research institutes and foreign policy institutes

• Persons who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

• Members of the main board of directors or its equivalent for organizations that have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

• Current and former members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee (proposals by current members of the Committee to be submitted no later than at the first meeting of the Committee after 1 February)

• Former advisers to the Norwegian Nobel Committee

Revised September 2016 by Norwegian Nobel Committe

According to the statutes of the Nobel Foundation, a nomination is considered valid if it is submitted by a person who falls within one of the following categories:

• Members of national assemblies and national governments (cabinet members/ministers) of sovereign states as well as current heads of states

• Members of The International Court of Justice in The Hague and The Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague

• Members of Institut de Droit International

• University professors, professors emerita and associate professors of history, social sciences, law, philosophy, theology, and religion; university rectors and university directors (or their equivalents); directors of peace research institutes and foreign policy institutes

• Persons who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

• Members of the main board of directors or its equivalent for organizations that have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

• Current and former members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee (proposals by current members of the Committee to be submitted no later than at the first meeting of the Committee after 1 February)

• Former advisers to the Norwegian Nobel Committee