Fijileaks reproduces Part Two of VICTOR LAL's analysis written during the height of the parliamentary hostage crisis in 2000. Lal examined the role of the Great Council of Chiefs and its future following George Speight's failed coup: The Fijian Commoners will be imprisoned by George Speight and Chiefs’ escapades: 'One dead, the other powerless to be born'

Deposed PM Bavadra with wife Adi Kuini;

Deposed PM Bavadra with wife Adi Kuini; Bavadra was Rabuka's hostage for seven days in 1987

The rise, fall, rise, and the fall of the Fiji Labour Party can be attributed to two primary reasons. In the perspective of history, the formation of the FLP and the statements of its leaders saw the rebirth of the 'agitational politics' whose origins can be traced to militancy among the Indo-Fijian labourers on the sugar plantations. The most notable were the strikes and riots of 1920 which, in the words of the historian turned Alliance government minister Dr Ahmed Ali, 'heralded a new facet of Indians: their assertiveness and willingness to enter into confrontation with other groups in their effort to obtain what they considered equality of treatment in a land to which they had come as immigrants but where they were fast anchoring permanent roots'. Their descendants have since continued the struggle and, with one notable exception, the strikes these days have assumed a multi-racial rather than a racial dimension.

We have already recalled Dr Baba's explanation on the shift in Fijian political thinking. In 1987 a Fijian sociologist, Simione Durutalo, who later became a founding vice-president of the FLP, blamed the British for introducing communal politics into Fiji and creating a situation of occupational specialization along communal lines. Durutalo, in terms of class struggle, condemned the Alliance and the NFP for perpetuating those divisions. He further maintained that the political nature of the crisis confronting the people of Fiji could not be discussed without a closer look at the state structure built up during the colonial period. He noted that in the phase of decolonization, power was transferred through virtually unchanged government institutions, to largely hand-picked heirs, the new ruling group in Fiji. For example, laws were changed from Ordinances to Acts but their contents remained the same. The colonial Parliament changed its name from Legislative Council to House of Representatives (with an appendix, the Senate) but its whole racial foundation and electoral system remained the same, as did the education and public health system, the Council of Chiefs, and the army and bureaucracy.

Durutalo also recalled the remarks of Professor Ron Crocombe of the USP that many Fijians failed to realize that what they believe to be their ancient heritage is in fact a colonial legacy. He claimed that the British used the economic disparity between the Indo-Fijians and the Fijians to increase the Fijian ruling class dependence for protection on the colonial government. The creation of the 1944 Fijian Administration, the NLTB and the constitutional guarantee on Fijian matters were cited as examples. Durutalo also charged that the British manipulated local, regional, and ethnic differences to emphasize divisive rather that unifying national interests. Such divisions were then deposited in the independence Constitution to assail the cohesion and survival of the new Fijian state from its inception. Ethnic differences, he maintained, and the use of the new Fijian chiefs, were the main instruments used by the colonialists to defuse and neutralize the 1959 Oil and Allied Workers' strike.

In summary, Durutalo, himself a commoner, indirectly appealed to the underprivileged Fijians and Indo-Fijians to unite and undermine the established political order. In his opinion this could be achieved 'if Fijian society produces the political will that is required to overcome the present impasse, and the labour movement, with the trade unions at the centre, is the only force which now has the potential to produce that political will to take us out of the present inertia'.

The Alliance Party responded in kind. Tradition was mixed with politics. For example, Ratu Mara, in his September 1986 address to a mini-convention of the Fijian Association, called upon the Fijians to remain united in order to retain the nation's leadership. He told the meeting that despite being outnumbered by Indo-Fijians, Fijians had political leadership; if they became divided this leadership would slip away from them. In reply, the future prime minister Dr Timoci Bavadra immediately criticized Ratu Mara for raising the race issue. He also lodged a formal complaint to the Director of Public Prosecutions asking him to investigate whether Ratu Mara's remarks contravened the Public Order Act, under which Butadroka was jailed for six months in 1977 for inciting racial hatred.

Bavadra went further: 'In previous elections, the Alliance fear tactic [included] asking people whether they wanted an Indian Prime Minister; now, with the historic uniting of all races under the umbrella of the Coalition, the leader is a Fijian, so the question is whether a non-chief should be Prime Minister. One would thus imagine that if an equivalent chief from another province challenged Ratu Sir Kamisese, the Alliance question would be: 'Can we let a Prime Minister of Fiji come from any province but Lau?'.

From this analysis emerge two inherently contradictory tendencies of exclusivism and accommodation among the conservative, nationalist and moderate Fijians. While the traditionalists were advocating the retention of the old established order, Durutalo was calling upon the disgruntled Fijians, especially the Fijian commoners, to respond to the demands of practical politics, rather than surrender to the forces of conservatism.

The rest is history. The FLP-NFP Coalition romped to power in the 1987 election with Dr Bavadra as prime minister, only to be cut down by a third-ranking Fijian soldier Sitiveni Rabuka and his cohorts. As for the change in the political landscape in 1987, with the Alliance, comprising mostly chiefs, becoming the major Opposition party, with Ratu Mara as leader, Ramrakha's words are instructive: 'And the Chiefs who have yielded so much power, and have made Fiji what it is today. Yes, they too have to recognise this change…a political adjustment has to be made. The genius of the Fijian people allowed them to cede this country and remain in charge of it. Their society has come down the centuries intact; their people still cling to their valued culture, tradition and customs.' But with a fundamental difference; the mutli-racial FLP-NFP Cabinet was like 'a new marriage taking place, a meeting of minds of the educated elite in Fiji, an elite which will bring in a new era to the country'.

In April 1987 it seemed that a majority of Fijians had quietly accepted the leadership change. Ratu Mara's resignation statement was also greeted quietly. He told the nation: 'You have given your decision. It must be accepted. Democracy is alive and well in Fiji…The interests of Fiji must always come first. There can be no room for rancour or bitterness and I would urge that you display goodwill to each other in the interest of our nation. We must now ensure a smooth transition to enable the new government to settle quickly and get on with the important task of further developing our country. I wish them well…Fiji was recently described by Pope John Paul as a symbol of hope for the rest of the world. Long may we so remain. God bless Fiji.'

But almost as soon as Bavadra and his ministers were sworn in, they began to attract not good wishes but a stream of curses. A Fijian nationalist movement calling itself the Taukei, led by no other than Tora and a few prominent Alliance personalities, sprang up. Tora announced a campaign of civil disobedience and called for the 1970 Fiji Constitution to be changed in so far as to guarantee Fijian chiefly leadership in government permanently. Shortly after the Alliance's defeat, its most powerful arm, the Fijian Association, convened a meeting and passed a vote of no confidence in the new government. Among those who attended this meeting, which was chaired by the newly-elected Alliance MP and FNP convert of old, Taniela Veitata, were Ratu Mara's eldest son, Ratu Finau Mara who was a lawyer in the Crown Law office; Qoriniasi Bale, the former Attorney-General; Filipe Bole, the former Minister of Education; and Jone Veisamasama, general secretary of the Alliance Party who, in 1983, was secretary to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the 1982 general election. What followed shortly before the historic coup can be summed up by two key players. Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, now the Leader of the Opposition, told Islands Business magazine of May 1988 that for more than six hours on April 19 he and Rabuka, later joined by Jone Veisamasama, 'talked about different options'.

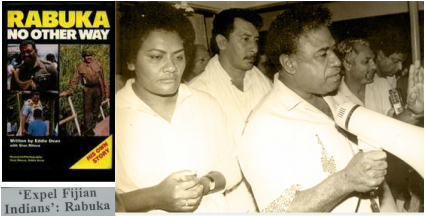

It was on 19 April that the groundwork for the coup was laid and according to Kubuabola, 11 May was the day his co-conspirators decided to proceed with its execution. He also claims that when it was learnt that Parliament would not sit on Friday they had agreed to bring forward the coup to Thursday. Another crucial intermediary between the Taukei Movement and the military, the Rev Tomasi Raikivi, provided his house in Suva as a centre for overall planning. Thus it was there that Rabuka met the other conspirators on Easter Monday, nine days after the defeat of the Alliance Party. We will let Rabuka explain the rest, as he did to Eddie Dean and Stan Ritova in his infamous autobiography No Other Way. He went to Rev Raikivi's for,

' … What he understood was an ordinary 'grog' party. It was early evening, and he just walked in, as he normally would, throwing his 'sevusevu' of yagona towards the bowl where the 'grog' was being mixed. 'I saw all these people sitting down, and realised it was some kind of a meeting. Some of the people greeted me, although I could not see everyone clearly because it was fairly dark in the lounge-room. Nobody asked me to leave.' When his eyes adjusted to the darkness, he discovered the gathering was 'quite a formidable group'. He says it included Ratu Finau Mara, Ratu George Kadavulevu, Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, Ratu Keni Viuyasawa, the brother of Brigadier Epeli Nailatikau, Filipe Bole, Ratu Jo Ritova of Labasa, Ratu Jale Ratum, 'Big Dan' Veitata, and the host Raikivi. Another leading light at this meeting was Apisai Tora.'

This handful of allegedly God-fearing men, some of chiefly rank, told their plans to Rabuka, exchanged opinions, and turned to Gold for help. On 14th May 1987 when the parliamentary session began at 9.30am, one of the conspirators, Taniela Veitata, stood on his feet to repeat to the House his October 1985 'Tribute to Chiefs' speech. The chiefs in Fiji were the guardians of peace, he declared. As long as chiefs were there, political power would never grow from the barrel of the gun. Unfortunately other races had not thanked the Alliance Party for its racial harmony. He did not spell out the punishment for the other races 'ingratitude' or pose the rhetorical question: what if chiefs are not in power?; in fact he did not have to, for shortly afterwards Lieutenant Colonel Sitiveni Ligamamada Rabuka, and a 'hit squad' of ten soldiers, led by Captain X, launched the first military coup against a democratically elected government of the South Pacific, ending the Coalition's 33 days in office.

In short, democracy died in Fiji on Thursday 14 May 1987; albeit temporarily. Captain X has been identified as Isireli Dugu, and his second in command was Captain Savenaca Draunidalo, the ex-husband of Adi Kuini Bavadra Speed. Rabuka later explained that it was the calling of God to execute the coup. Another was the frontal attack on the 'chiefly system' and its rightful place in national politics; and the personal attacks on Ratu Mara, that Rabuka claimed were too much for ordinary commoner Fijians.

What happened in the next years until the passing of the new non-racial Fiji Constitution; the rise to power of FLP, and the demise and rise of Rabuka - the 'Hero of the Fijian Revolution' need not be revisited except to point out that the Great Council of Chiefs appropriated to themselves a high profile role during these turbulent years.

In 1972 the Great Council of Chiefs (Bose Levu Vakaturaga) took a bold step forward-the Council decided that members of Parliament in both Houses who were indigenous Fijians would be members of the Great Council of Chiefs. By doing this, they gave out three NFP Members of Parliament, Captain Atunaisa Maitoga, Isikeli Nadalo, and Apisai Tora a voice in the Council of Chiefs. This move, taken quietly and without any fuss or bother, according to Ramrakha in 1978, came as a great surprise to the Members concerned, and they took full advantage of it all. But it was a major concession to make. Here were these members who belonged to a Party that was undoubtedly predominantly non-Fijian in membership, and was often suspect in the eyes of the rank and file Fijian, and its members were freely allowed to participate in the deliberation. It was a thoroughly progressive move on the part of the Council. And yet the leader of the NFP, Siddiq Koya, made a blunt call for its abolition.

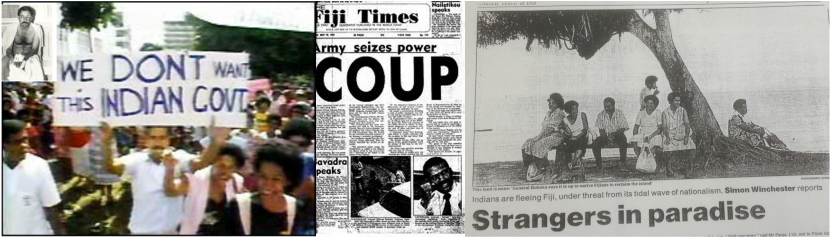

The NFP had often advocated absorption of the Fijian Affairs Board into the mainstream of political life and coming under the ageis of one single administration, and it had advocated the ultimate redundancy of the NLTB by giving titles to the Fijians, and giving them the incidents of ownership short of power of sale. Reaction to Koya was savage. Personally, Ramrakha remained unconvinced that the Council of Chiefs had outlived its usefulness. On the other hand, the Chiefs themselves 'must recognise that we live today in a basically democratic society, and that changes will have to come'. Ramrakha continued: 'I would ask the Chiefs to behave as Chiefs: there are many mountains to be moved; there is a great deal they have to do. Your society still looks to you to deliver the goods-you are subjected to old pressures, and new ones. The only reservation I make of the Great Council of Chiefs is that we do not hear enough from them.' Ramrakha had uttered these words two decades ago; in the 1987 street demonstrations against the Bavadra government, led by Tora and others, he however found himself the target of Fijian anger through one of the placards which read: 'K.C. Ramrakha-the deserter, shut up.'

Ironically, these Fijian demonstrators were totally oblivious to Ramrakha's role at the 1970 Constitutional Talks where he and other NFP delegates gave the Council of Chiefs the power of veto on decisions affecting the Fijian race. Another irony, in fact a comical farce, was the pronouncements of Tora at the demonstrations: 'We shall recover the rights of Fijians sold out in London in 1970. We have no need for your system, your democracy. We shall never have such things imposed on our paramountcy…They [Indians] have tried to blackmail us with economic power. It is becoming Fiji for Fijians now. We took in the Indians which Britain brought us…They won't learn our language, our customs, join our political parties. It is time for them to pack and go.' What Tora failed to tell his fellow demonstrators was that he had changed his name from Apisai Vuniyayawa Tora to Apisai Mohammed Tora after becoming a Muslim while serving with the Fijian forces in Malaya. He had provided the prefix 'National' to the Federation Party to form the NFP. As recently as July 1986 he asserted that 'Government policy is that Indian people are here to stay whether people like it or lump it. Without Indians Fiji would never have been what it is today, economic-wise and otherwise.'

Moreover, the Great Council of Chiefs finally gave to Ramrakha more than he may have bargained for in the 1970s. In the name of Fijian ethnicity, they hurriedly endorsed Rabuka's revolution and seized a large chunk of responsibility on behalf of the Fijian people through the promulgation of a new Constitution in 1990. In their pursuit for total and absolute control the chiefs, however, were also beginning to lay the foundation for their own gradual destruction for history, time, and the people were no longer totally on their side, not to mention the Colonial government.

As a Maori professor, Ranginui Walker, declared in Auckland in 1987: 'The coup is nothing more than a shameful use by an oligarchy that refuses to recognize and accept the winds of change in Fiji. It would appear from this distance that the Great Council of Chiefs, still living in their traditional ways, have been misled. Their land rights are secure under the 1970 Constitution. But because they have not been taught their rights, they are readily manipulated and swayed by demagogues.'

The Chiefs find new berth with SVT

The chiefs also launched a new political party, Soqososo ni Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT), that it hoped would unite the Fijian people under one umbrella. The reality, as we know from the recent election results, turned out to be quite different. Some Fijian leaders questioned the wisdom of the Council of Chiefs, as a formal non-political institution, to sponsor a political party. Tora wanted to know what would happen to the dignity of the Council if it failed to capture all the Fijian seats. 'Our firm view,' he said, 'remains that the Bose Levu Vakaturaga should be at the pinnacle of Fijian society, totally removed from the taint of ordinary politicking'. The biggest shock was the election of Rabuka, a non-chief, to lead the SVT, who defeated Ratu William Toganivalu and Adi Lady Lala Mara. Butadroka was quick to respond: 'If the SVT delegates can put a commoner before the chief, then I don't know why a chiefs-backed party can do such a thing. - putting a chief-in this case the highest ranking chief, Ro Lady Lala-before a selection panel.'

The greatest shock of all was the recent election of Rabuka as the first 'independent' chairman of the Great Council of Chiefs. It is not surprising therefore to read of Ratu Mara's expressed concerns. Shortly after the first coup Rabuka wanted to exclude commoners from the Great Council of Chiefs altogether: 'I respect chiefs. I do not like the composition of the Great Council of Chiefs. There are so many non-chiefs there who will try to dictate the resolutions of the Great Council of Chiefs. The Chiefs are so humble, their personalities and their character do not make them forceful enough when they discuss matters. They will agree, they will compromise…whereas those who are not Chiefs in there tend to be very, very selfish.'

After Rabuka secured the prime ministership, he however began to develop ideological justifications for his ambitions. In August 1991, while professing to be a loyal commoner, he wondered whether it was appropriate for chiefs to involve themselves in electoral politics. Their proper role was at the local village level, because 'when it comes to politics, the chiefs do not have the mandate of the people'. While counting himself as an ideal candidate for leadership he reiterated that 'there are a lot of capable commoners who can play a very, very important role in the Fiji of the next decade'. He pointed out that 'the dominance of customary chiefs in government is coming to an end' and soon 'aristocracy' would be replaced by 'meritocracy'. Ratu Mara, who thought Rabuka was an 'angry young man, speaking off the cuff in any instigation', also faced Rabuka's wrath. Rabuka described Ratu Mara as a 'ruthless politician who has been allowed to get away with a lot. Maybe it's because of the Fijian culture that he is a big chief and because he was groomed well by the colonial government'.

The sudden change of Rabuka's tune on chieftaincy can be best illustrated by quoting Jone Dakuvula, a cousin of Rabuka. Accusing the 'colonial' chiefs of keeping the commoner Fijians in political subjugation and economic morass, Dakuvula had personally challenged Rabuka on Fijian unity, specifically for his remarks during the two coups that 'I want all the Fijian people to be on one side. The whole thing is a solidarity of the Fijians and then we can compete'.

In Dakuvula's words, 'This reactionary notion has no basis in history or current realities. We Fijians have never been united at any time, either at the village level or national level. The various confederations of competing and warring vanuas, now roughly reflected in the provinces, outline these divisions. Any experienced village chief will tell Colonel Rabuka that all Fijian villages are riven with competing divisions along family, tokatoka, mataqali and other lines.' Furthermore, Dakuvula maintained that any chief who claimed to command his villagers' loyalty and unity at all times these days was 'a liar'.

He said Rabuka need look no further that the position and history of his mataqali. Dakuvula went on the claim that 'what the Taukei Movement and the Great Council of Chiefs proposal will achieve is the exact opposite of what they desire: it will result in provincialism, parochialism, unhealthy rivalries, patronage, corruption and the discrediting of the chiefly system'. Strangely Rabuka, on becoming prime minister, himself began to invoke the 'Melanesian' model of achieved leadership against the 'Polynesian' model of ascribed leadership. He compared his paramount chiefs (Mara included) to the banyan tree 'where you don't see anything growing', and suggested that they should step down.

Chieftainship versus Democracy

A general review of the trend of events clearly reveal that commoner Fijians have become increasingly strident in their criticism of the traditional chiefs, displaying spontaneous or calculated outbursts of individualism. One governor, Everard im Thurn, in 1905, dared to point out that excessive subordination of the Fijian people by their chiefs was a serious impediment to their progress and, indeed, a danger to their survival as a race. In his opening address to the Council of Chiefs, he outlined what were to him the worst aspects of chiefly rule in Fiji:

'You Fijians have done very little to help yourselves. You few chiefs are fairly prosperous. But your people-such of them as are left-are mere bond servants. They work for you partly because the law to some extent compels them. The reason why they do not care to work more for themselves is that your chiefly exactions prevent them from gaining anything for themselves-and property to make life interesting to them…Do you know what we mean by the word 'individuality'?…the man that has individuality uses his own brain to guide his own actions. He thinks for himself…he uses his own hands for his own benefit. To him life will be worth living. That is the habit of thought which we and you should encourage the Fijians.’

The late Dr Rusiate Nayacakalou, in his study of modern and traditional Fijian leadership, warned that 'attempts to displace existing leaders are viewed with suspicion and jealousy and may be met with drastic action'. It also reflects the trauma of an indigenous people struggling to encompass tradition within the framework of democracy. Ratu Mara's call for respect of the chiefs is a familiar one. When the SVT was formed, Durutalo said: 'This is the last hurrah of the chiefs. It is an attempt to stem the tide and salvage their hold and support of the Fijian people. There has been a gradual erosion of their political influence, accelerated particularly in the urban areas and this is a last ditch attempt to contain that'. The perennial question is how: through chiefship or democracy?

We often hear in Fiji that 'a chief is a chief by the people'. On 6 May 1972 Ratu Mara told the Fiji Times that 'there is a misconception that the chiefs form a club and think as group…The chiefs are the chiefs of a group of people. They think more in line with the groups of which they are chiefs rather than their own class'.

But one Tevita Vakalomaloma argued five years later (2 February 1977), in a letter to the Fiji Times to the contrary: 'Most of the Fijian chiefs no longer serve their people. In fact most of them think that the people have nothing to do with their privileges and status. What they are forgetting is that they are what they are because they have people below them. In other words, a chief is a chief because he or she is supposed to have some people to lead'.

The Alliance however blamed the Fijian Nationalist Party for the sorry state of affairs. In the Nai Lalakai (14 November 1977) it charged: 'They [the FNP] have divided families, mataqalis, villages, vanuas and our race, severing our Fijian bonds, weakening our traditional and religious life and our political unity.' The FNP, however, argued to the contrary, claiming that it was under the Alliance chiefs that Fijians so-called special rights and interests had been exploited for the chiefs' own economic and political benefits. In 1989 the FNP submitted that the chiefly system be abolished altogether.

What is really at issue, then, is what form of leadership should the Fijian commoners follow to remain within the traditional communal system? In 1982, the old Fiji Sun newspaper editorial, commenting on the Bau resolution, called for its rejection as well as a firm statement from the Alliance government, and put the issue in perspective: 'The sticking point is the question of the place and role of the chiefly system, now and in the future. It is not possible for the two systems to operate in tandem successfully at national level.' It is clear from recent pronouncements that the modern day chiefs still live, or pretend to live, in two worlds, 'one dead, the other powerless to be born'.

The great Fijian leader Ratu Sukuna was also a man of two worlds, that of the traditional Fijian and the official European. His biographer, the Australian Deryck Scarr, a rabid anti-Indian historian, argues that Sukuna attempted to keep the Fijian society close to its 19th century moorings, to the 'classic patterns of his childhood'. For Sukuna, 'the true religion of the Fijian is the service to the chief'; he was cynical on the value of democracy, and as an aristocrat, remained sceptical about 'how far ability can carry a man in modern society'. Ratu Mara, in the preface to Scarr's biography, Ratu Sukuna: Soldier, Statesman, Man of Two Worlds, (1980), hails Ratu Sukuna for bringing the Fijian society into the 20th century.

But as one reviewer of Scarr's book put it, 'the Fijian people cannot afford to contract out of the 20th century and seek succour in the traditional society of Sukuna's childhood'. Moreover, Ratu Sukuna had little understanding of, and even less sympathy for, the predicament and aspirations of Indo-Fijians, 'Mother India's more enlightened children', who should have accepted their designated place in the colonial hierarchy instead of challenging it, and whose lives were deeply affected by Ratu Sukuna's activities.

The self-contained, self-sufficient Fijian world of Ratu Sukuna's time, and that of other high Fijian chiefs like Ratu Mara, has vanished beyond recall. Ratu Sukuna's view on the rightful education of Fijian commoners may be the starting point of the historical departure. He believed, 'in bigger and brighter villages, with schools teaching, for the most part, agricultural subjects and handicraft rather than academic groundwork'. It seems that the modern day commoner Fijian has other perspectives on education and political power in contemporary Fiji. He believes in 'ability' and not 'chiefly' status for his or her rightful place in Fijian society.

The Educated Fijian Commoner: A Mule or a Galloping Horse?

It is interesting to draw a parallel with educated commoner Fijians and their rightful place in Fijian society with those of the sons and daughters of Indo-Fijian indentured labourers. There was firm opposition towards education of Indo-Fijians. A former chairman of the Levuka School Board, D.J. Solomon, told the 1909 Education Commission:

'If an Indian desires to educate his children let him pay for it himself. This question should not be considered one moment by the Government, for to educate an Indian is to create inducement for crime on the part of the educated Indian and oppress the uneducated Indian'. The Methodist missionary, Rev J. W. Burton, had this qualification: 'The training which suits admirably a boy at Eton (in England) or one in our Australian High Schools may not be useless., but probably vicious in its effect upon a Fijian nature. We have made a tragic mistake in India in raising up a few to inordinate heights of suitable education and thus divorcing them from usefulness to the Commonwealth. A half-educated Indian babu, with his staccato English and metronomic syllables is torture enough; but a Fijian babu-! May heaven forfend'.

The manager of the Vancouver-Fiji Sugar Company, E. Duncan, in 1914, was not to be outdone: 'We most emphatically do not require an Indian community of highly educated labourers, with the attendant troubles the 'baboo' class has brought to the Indian government teaching and preaching sedition and looking generally for immediate treatment on a parity with educated Europeans accustomed to self-government for many centuries. We require agriculturalists only and the education provided by the colony (or planter) should for that reason be but elementary, and in as far as possible, technical on these lines'.

The quotations provided illustrate in detail, according to Dr Ahmed Ali, the former Education Minister in Mara's Alliance government, 'European attitudes towards Indians and the place that they felt Indians should have in Fiji. Not surprisingly their views were in conflict with Indian aspirations. Their determination to keep Indians as labourers and to deny them equality and reserve for them a separate compartment in the colony were also steps that thwarted the integration of Indians into the wider society. Europeans who opposed them did so not only because of beliefs in Anglo-Saxon racial superiority but also through fear and resentment of Indian competition'.

A similar parallel can be drawn between the role and place of commoner and individual Fijians in the overall Fijian traditional society vis-a-vis the chiefs and the Great Council of Chiefs. The rise of commoner Fijians through the Fiji Labour Party in 1987 brought the conflict between commoners and chiefs to the forefront of Fijian politics. Their dissent and criticism of the chiefly leaders could not be dismissed as racially motivated attacks upon Fijian institutions. They refused to abide by the tenets of tradition and custom while the chiefs were entering the world of commerce and business and doing well for themselves.

As Bavadra asserted: 'By restricting the Fijian people to their communal life style in the face of rapidly developing cash economy, the average Fijian has become more and more backward. This is particularly invidious when the leaders themselves have amassed huge personal wealth by making use of their traditional and political powers'.

It can be argued that modern-day Fijians (teachers, doctors, journalists, skilled workers, and civil servants) represent, in many ways, the coming of age of a new generation of Fijians who have achieved success by the dint of their individual efforts and sacrifices. They are role models for the young Fijians and not the tradition-bound chiefs of the Fijian villages.

Why? As Professor O. H. K. Spate had reminded us in 1959, 'The functions of the chief as a real leader lost much of their point with the suppression of warfare and the introduction of machinery to settle land disputes, but constant emphasis seems to have led to an abstract loyalty in vacuous, to leaders who have nowhere to lead to in the old terms and, having become a sheltered aristocracy, too often lack the skills or the inclination to lead on the new ways. Hence, in some areas, a dreary negativism: the people have become conditioned to wait for a lead which is never given.' The impasse could only be broken with the advent of liberal democratic values, of which individualism as the defining characteristic.

But it seems that the chiefs, averse to individualism, have once again turned to the chiefly system, a system which according to the late Bavadra, 'Is a time-honoured and sacred institution of the taukei. It is a system for which we have the deepest respect and which we will defend. But we also believe that a system of modern democracy is one which is quite separate from it. The individual's democratic right to vote in our political system does not mean that he has to vote for a chief. It is an absolutely free choice'.

Democracy, that great swear word which denotes freedom and choice, is the Achilles heel of Fijian politics. The question is: whose version of democracy - the Fijian or European one?

On 16 December 1965, speaking in the Legislative Council, Ratu Mara, while arguing against common roll which would bring Indo-Fijian domination, argued that it was European culture 'to which only we will submit as Fijians, and to no other culture'. In 1987, on losing power, he claimed that 'Democracy is alive and well in Fiji'. In other words, the people of Fiji, including the commoner Fijians, had exercised their democratic right to choose who should lead the Government of Fiji. The FLP-NFP victory brought to the fore also the true and proper place of the traditional rulers and the chiefly system in modern Fiji.

Overall, in the 1987 general election there was a genuine meeting of minds of educated commoner Fijians and the descendants of educated coolie Indo-Fijians, the two groups most feared by the chiefs, colonialists, and Indo-Fijian merchants in Fiji. For the next 33 days, the people of Fiji enjoyed their choice of government until Rabuka, with his 'men on horseback', came on the scene to proclaim: 'The chiefs are the wise men in Fijian society, guardians of our tradition. Take that power away and give it to the commoners and you are asking for trouble.'

Will he now, as a commoner, hand back the power - the chairmanship of the Great Council of Chiefs- to the traditional chiefs, as many are demanding from him, including George Speight.?

The Great Council of Chiefs has once again ridden on the minority crest of Fijian racism and nationalism to portray themselves as ”fathers of the nation”

George Speight and a circle of inward-looking commoner Fijians, it seems, have once again set back the opportunity for commoner Fijians to create a multi-racial Fiji where their own individuality and voices could be heard in the affairs of the nation. They have consigned commoner Fijians to be the subservient 'educated mules' of the chiefs, as the chiefs allegedly were in colonial days to the British.

It will take a long time for Fijian commoners to be individual, strong-minded, and fiercely independent 'galloping horses' in a multi-racial and modern Fiji, and the larger world around them?

The Great Council of Chiefs has once again re-inserted itself at the helm of Fijian politics – through the backdoor and with the help of a barrel of a gun.

In the guise of Fijian nationalism, George Speight has escaped from the clutches of the law for his alleged criminal activities in a court of law and the Great Council of Chiefs have once again stepped into the centre court of power which was gradually slipping away from their clutches.

The commoner Fijians will be made to pay the price for Speight and the chiefs’ great escapades.

The release of the hostages means that Fijian commoners, led by their chiefs, have once again being imprisoned in the cloth of tradition, although 'tradition should be a guide and not a jailor’. - VICTOR LAL, July 2000