By VICTOR LAL

Fiji's Daily Post, July 2000

The Fijian Commoners will be imprisoned by George Speight and Chiefs’ escapades: 'One dead, the other powerless to be born'.

The failed businessman turned rebel coup leader, George Speight, might have succeeded in ousting a democratically elected government and escaping criminal charges but in the process he and his henchmen have set back the progress and development of ordinary Fijian commoners.

In their crude racist submission to the Great Council of Chiefs, the group have once again silenced the voices of their ordinary fellowmen who seemed to have been coming out of the shadow of their chiefs. In stripping Mahendra Chaudhry of his political power, the group have, in fact, stripped the ordinary Fijian of his or her power.

For once again, it is the traditional chiefs who are being called upon to decide the fate of the Fijians and non-Fijians alike: the very role they were groomed to perform during Fiji’s turbulent history.

The Circus Showman and Educated Mule

In the old and dusty records of the British Colonial governors experiences, stored in the vaults of Rhodes House, the University of Oxford's library on Colonial and Imperial studies, I found the following letter to the Colonial Office in London from one of the many governors to Fiji, Sir George O' Brien. The letter, written from Government House in Suva, is dated the 14th of December 1897. The subject matter is Britain's policy of governing Fiji through the native chiefs. Governor O'Brien, who successfully argued against the federation of Fiji with New Zealand and Australia, wanted to express his mind on 'native policy' in a few words privately. And he did indeed, in a language which made me cringe on the first reading of his letter.

The Governor O’Brien’s Letter

The colonial governor O'Brien begins his letter by informing the Colonial Office that 'the situation in Fiji reminds one of nothing so much as the story of the circus showman & and his educated mule.' He continues the letter in the following vein: ''Ladies & gentlemen'', he (the showman) is reported to have said, ''you see before you a most remarkable animal - an educated mule. I have educated him myself. For the last 15 years I have done nothing but educate him. And the consequence is that I am in the proud position to-night, as I shall presently show you, of being able to make him do anything I like.'' Governor O'Brien continues:

'So with the Fiji Government and the Chiefs. After many years of governing Fiji through the chiefs we are able to make them do anything we like.'

It is not surprising, therefore, that some radical native Fijians have branded the chiefs as 'colonial or bureaucratic chiefs'. Others have accused them of being experts at political manipulation; they are fronts for big-time multi-national companies and commission agents, they promote racial hatred; they thwart every genuine move towards national cohesion and democracy; in short, theirs is, in many senses, a role actually subversive of the unity, progress and stability of this country. They have held back the economic, educational, and political progress of commoner Fijians. The very existence of these traditional rulers is inconsistent with the main goal of our struggles and efforts: building a united country, democracy, and a just, fair and stable political order.

Some claim that the Great Council of Chiefs, based as it is on inheritance, is not only thoroughly undemocratic, but most of those who man it are part of the tiny class of Fijians whose activities are some of the main causes of the country's racial problems. If democracy is to grow and flourish, its roots must be planted in a healthy, vibrant soil, and not on a murky and undemocratic foundation. The radical Fijians claim that at the grass-roots level, democratic structures, specifically democratically elected village, district, and local government councils and committees, manned by the elected representatives of the people should be established to decide matters of Fijian and national concern.

The defenders of the chiefs, on the other hand, have welcomed them as 'boundary-keepers' or mediators between different races who have used their authority and prestige, not to mention the strong weapon of coercion at their disposal, to stabilise crisis situations, and only to re-establish their chiefly control of Fiji.

Understandably, the deposed President and the paramount chief of Lau, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara was concerned with the way politicians played with the lives of his people during the last elections. Addressing a meeting of the Lau Provincial Council in Moala, Ratu Mara said these were evident in the statements made, in which chief's were insulted. In a sombre tone, the President and Tui Lau, Ratu Mara asked why statements such as 'don't elect your chiefs but elect a commoner because its easier to deal with them' were made to his people only. And according to Ratu Mara, the situation was worsened when the leader making those statements said nothing about other high chiefs from other provinces. He named numerous provinces whose high chiefs also contested the May elections.

Ratu Mara was referring to statement by the former Prime Minister and leader of the Soqosoqo ni Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT), Sitiveni Rabuka, now the chairman of the Great Council of Chiefs. The former PM had made such statements saying it is easier for the common people to approach commoner parliamentarians with their needs than it is to go to chiefs for help. Ratu Mara said he has been dwelling on the issue for quite sometime and has reminded his people, that those who are chosen to lead in government must always respect their chiefs. He asked the meeting to discuss ways in which all the chiefs in the province could support each other.

Traditional Authority in Colonial Era

British colonial rule was established following the Deed of Cession in 1874 whereby Fiji became a possession and dependency of the British Crown. In Ratu Seru Cakobau's words, the self-styled 'King of Fiji', the British were called upon to 'exercise a watchful control over the welfare of his children and people; and who, having survived the barbaric law and age, are now submitting themselves under Her Majesty's rule to civilization'. Of the several factors that had compelled the Fijian chiefs to pass their country to the British Crown, one was the menacing threat from the restless white settlers. Soon after the Deed of Cession the British government appointed the aristocratic Sir Arthur Gordon Hamilton (later Lord Stanmore), as the first Governor of Fiji.

The youngest son of the forth Earl of Aberdeen, in Scotland, Gordon, who had earlier ruled Trinidad (1886-70) and Mauritius (1870-74), arrived in Fiji with a reputation-although his true intentions have since been closely questioned-as 'an uncompromising guardian of native rights', and his influence can still be found in the land policies in Fiji. He also introduced a new ethnic group into Fiji-the indentured Indian labourers-in order to provide a work force for the colony's cane fields, while simultaneously safeguarding Fijian culture through the chiefs.

Consequently, the chiefs-Fiji's traditional rulers-were recognized by the British colonial government. Through the system of indirect rule, evolved by Lord Lugard in West Africa, and applied by his successors elsewhere, separate Fijian institutions were established to facilitate ruling them. These institutions, while creating a 'state within a state', gave the Fijian chiefs limited powers to rule their subjects, and to deeply influence the subsequent history of the colony. The objectives underlying Gordon's policies were similar to those which had given rise to colonial practices elsewhere: a divide and rule policy whereby the colonial government divided in order to rule what it integrated in order to exploit.

The partnership between the chiefs and Gordon not only enabled, according to the historian R. T. Robertson, 'the domination of the eastern chiefs particularly over the west, but it also resulted in the rise of a new type of bureaucratic chief, aware of the need to adjust to the demands of the colonial state if they were to achieve their class aims'. Others have written elsewhere that the ruling Fijian class had greatly benefited from colonial education, as the Council of Chiefs demanded that Fijian commoners should not receive education in the English language. The result was that very few Fijians, mostly of chiefly rank, entered the civil service as junior members of the 'bureaucratic bourgeoisie'. The white planters of the colonial era, however, condemned Gordon's native policy, and saw one of the most powerful chiefs in Fiji as only fit to be a white man's gardener. But the chiefs saw their roles through a different mirror-as guardians of the commoner Fijians.

It must be pointed out that the Deed of Cession was never universally accepted by Fijians, especially those of western and central Viti Levu. These people were the first to rebel against the colonial order, 'believing that it implied also domination by eastern chiefs who had signed the Deed of Cession'.

Chiefs in Post-Independent Fiji

When Fiji became an independent nation on 10 October 1970, it was the traditional eastern chiefs in the Alliance Party who took control of the nation's political leadership, with only two brief interruptions in 1977 and 1987. It was only in the recent elections that the chiefs found themselves not at the helm of government. The first high-profile challenge to chiefly rule came from one Apolosi Nawai [described as the Rasputin of the Pacific], who was banished to the island of Rotuma in 1917, 1930 and 1940 for portraying himself as the Messiah of the Fijian people. The demise of Nawai, however, failed to discourage other Fijians from taking up the challenge.

In the 1960s it was Apisai Tora who was in the forefront of western dissent against the eastern chiefs; in the 1980s it was Ratu Osea Gavidi and his Western United Front. But in 1973, the late Sakeasi Butadroka, a former Assistant Minister in the Alliance government, declared an all-out verbal war on Ratu Mara. The legitimacy of chiefly rule, based on traditional norms, faced an internal challenge. Butadroka himself is from a non-chiefly background and hails from Rewa province whose paramount chief is Adi Lady Lala Mara. But Butadroka described his dispute with Ratu Mara as a political one claiming that 'European politics and traditional matters are two different things'.

He went on to state that 'in traditional matters I greatly respect this man of noble birth and I have also reverence and try at all times do what is right'. Thus Butadroka (a man who had 'lost his senses', according to Ratu Mara) permanently revolutionized Fiji's politics, paving the way for other disgruntled Fijians to follow suit in the future. He had finally broken the tenuous thread of political tolerance for the chiefs, and the effects were to be felt in the future, especially during elections in Fiji.

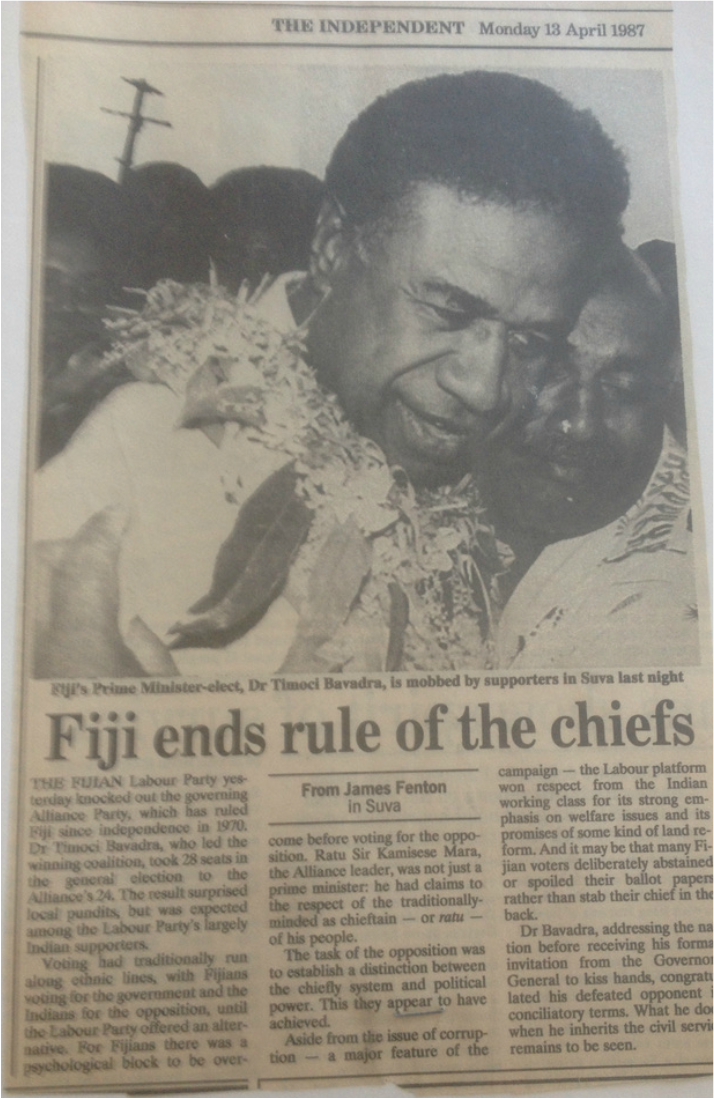

In the 1987 general election, the Co-Deputy Prime Minister Dr Tupeni Baba, than the chief spokesman for the NFP/FLP Coalition, offered the following explanation as to why the Fijians were no longer going to elect people merely because they were chiefs: 'The Fijians have always viewed the Alliance as being the Fijian party. That base is being eroded. For the first time Fijians are being offered a list of credible Fijians standing against the Alliance. These Fijians can match the Alliance on its own front. They have comparable experience and now-how. For the first time there are Fijians who are willing to sacrifice their jobs and positions. Fijians will no longer elect people merely because they are chiefs.'

The Coalition seemed to have caught the Fijian people's imagination. The message to them was clear, as the late Prime Minister Dr Timoci Bavadra told one Fijian political gathering: 'There is a need to realize the difference between the traditional role and our democratic rights as citizens of this country.' He also called on the Alliance Party to stop employing abuse of Fijian tradition as a means of furthering its political ambitions. In a statement apparently directed at other Fijians caught in the traditional struggle, Bavadra made his position clear: 'I have great respect for both my great uncles, the Tui Vuda and the Taukei Nakelo in so far as the traditional chiefly system is concerned. But I beg to differ from both of them as far as political belief and standing are concerned…My loyalty to the Tui Vuda as chief of the Vanua is unshakable. But as far as my political affiliation is concerned I owe allegiance to my party. We belong to two different parties and we have different ideologies.' Moreover, the sorry state of the Fijian's plight must be blamed on the Alliance, for it was under the Alliance government that the Fijian remained in the economic backwater. The Alliance hit back with a vengeance.

Some leading Alliance candidates demonstrated the resurgence of Fijian nationalism in a bewildering variety of pronouncements. For example, Ratu David Tonganivalu warned that the Fijian chiefs must remain a force for moderation, balance and fair play against such extremism. He said the chiefs were a 'bulwark' of security for all and custodians of Fijian identity, land and culture. Ratu David, himself a high chief, said to remove chiefs would 'pave way for instability'. Ratu Mara also joined the political fray. Declaring that 'I will not yield to the vaulting ambitions of a power-crazy gang of amateurs-none of whom has run anything-not even a bingo', charged that there was an FLP ploy to destroy the chiefly system.

Dr Baba, speaking for FLP, denied these charges. He accused Ratu Mara and others of attempting to reverse the tide of history in order to prevent the old Fijian order from dying, saying it was a desperate bid by Ratu Mara to cling to power, and added that political manipulation of Fijian people's emotions on the eve of a general election devalued democratic leadership. Whether the Alliance was attempting to reverse the tide of history or not is questionable, but one thing is clear; history was not only repeating itself but had come full swing, except that the main players now were Fijian commoners versus the chiefs. In the past, it was the Indo-Fijian politicians who used to take the Fijian chiefs to task over political and traditional authority. The establishment and perpetuation of the separate Fijian Administration however made it extremely difficult for them to establish alternative bases of legitimacy.

The Chiefs and the Indians

The Indo-Fijians are all chiefs and no commoners. In the context of Fijian politics, therefore, their political leaders have always found themselves caught in the conflicting traditional, bureaucratic, and charismatic forms of authority in Fiji. The Indo-Fijian leaders had agreed to confer veto power to the chiefs in the Senate during the 1970 Constitutional Talks in London, which meant that for the first time in Fiji's history, the Great Council of Chiefs suddenly enjoyed its say in the mainstream of Fijian politics. In the old colonial days, much of what was deliberated was often decided in advance by judicious consultation between the chiefs and the colonial administrators.

Ironically, in post-independent Fiji it was the very Indo-Fijian leaders who attracted virulent criticism whenever they condemned the 'political chiefs' in the Alliance Party or their traditional institution-the Great Council of Chiefs.

In the 1982 general election the Indo-Fijian leaders were accused of collaborating with the infamous 'Four Corners' programme on elections in Fiji which claimed that the present leaders of Fiji were descendants of the Fijian chiefs who 'clubbed and ate their way to power'. But the most vicious attack on the Indo-Fijian leaders was made in the Senate where one Fijian senator, Inoke Tabua, stoutly defended Ratu Mara, his paramount chief. He warned: 'I want to make it clear in this House that whoever hates my chief, I hate him too. I do not want to make enemies but to a 'Kai Lau' like me, if someone is against my chief he is also against me and my family right to the grave.'

Tabua refused to isolate politics from chieftaincy. Understandably, as Ratu Mara himself had told the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the 1982 election that his evidence should be considered and treated in the light of his three main roles in Fiji: 'On the one hand I live, think and act as an ordinary citizen of this State and also as a chief in the Fijian traditional social system. I am also a politician and leader of the Alliance Party, which is closely interested in these proceedings. And, lastly, I am Prime Minister of this State and leader of its government.' It was these three roles that dominated the sentiments and minds of Fijians when it came to passing judgement on the actions of Indo-Fijian leaders during the general election. They invoked their traditional ties with their chiefs to condemn the Indo-Fijian leaders.

The Ra Provincial Council and the Great Council of Chiefs, through two resolutions, tried to reassure the Fijian people of their determination that Fijians should, and always would, rule Fiji. The first tentative step was taken during a meeting of the Ra Provincial Council which resolved that the offices of Governor-General and Prime Minister must be reserved for Fijians and that this should be the subject of constitutional changes, a demand first voiced by Butadroka's FNP in the 1970s.

The Council also proposed that the composition of the House of Representatives should be two-third Fijian and one-third all other races. The Council also resolved that the two resolutions be forwarded for inclusion on the agenda of the Great Council of Chiefs meeting scheduled for November 1982. Council members were of the opinion that the issues should be discussed at the Bau meeting, when the chiefs from the various traditional Fijian confederacies discussed issues of Fijian interests.

Both resolutions were condemned by the Western United Front (WUF) and the NFP, then in a Coalition pact for the 1982 election. The WUF expressed surprise that some Fijians still felt so strongly about the last general election and dismissed as totally unfounded the allegations that the Fijians and their traditional systems had thereby been insulted. WUF also considered that there was nothing derogatory in the 'Four Corners' programme. While linking the programme with the Alliance's involvement with the Carroll team, WUF's general-secretary said, 'Cannibalism was part of life in Fiji in the early days and we Fijians are descendants of cannibals. What is wrong with that? Only powerful chiefs in those days enjoyed on bokolas. I cannot find why some Fijians are annoyed about the Four Corners programme'.

The Great Council of Chiefs moved to endorse the two manifestly racist resolutions thus presenting itself in the eyes of the Indo-Fijian community as the political champion and promoter of Fijian nationalism, as preached by the FNP. The resolutions were finally passed despite the abstention from Ratu Mara and then Deputy Prime Minister, Ratu Penaia, who pointed out that to change the Fiji Constitution required the consent of a two-thirds majority in both Houses. The role of Ratu Mara, who abstained from voting, did nothing to allay Indo-Fijian fears. As an NFP/WUF Coalition statement later charged: 'It should be apparent even to a political novice that the whole exercise was carefully stage-managed to intimidate non-Fijians, especially Indians and the Fijian supporters of the Coalition'.

It also expressed surprise that Ratu Mara had abstained from voting rather than opposing the two resolutions. Ratu Mara replied angrily that he 'was is no way obligated to his political party to say what he did or said in the Council'. It was during the debate on the resolution that trade unionist Gavoka had likened Indo-Fijians to dogs; and Mrs Irene Jai Narayan, branding the Bau resolution as racist, went on to state: 'To liken Indians to dogs…is a grave and unwarranted provocation to the entire Indian community. It is now obvious that those indulging in the abuse of Indians are not reacting to any so-called insults…[but] because the NFP/WUF Coalition dared to challenge for power in the last general election and came within a whisker of wresting it from the Alliance.'

Mrs Narayan further observed: 'It is indeed curious that the controversial motion came up while the Prime Minister claims that the worst insults he received were from Fijians themselves, why the focus of attack and resolution adopted by the Great Council of Chiefs have been designed to rob of the few rights they (Indians) have left to live in the country of their birth.' Clearly, the statement continued, racial policies espoused by the FNP leader, the commoner Butadroka, had found greater favour with the chiefs than had the so-called multi-racial policies of the paramount chiefs leading the Alliance Party.

Another Fijian senator, Ratu Tevita Vakalalabure, warned that unless Indo-Fijians united with Fijians and if what happened in the 1982 general elections was repeated at the next, probably 1987 election, 'Blood will flow, whether you like it or not. I can still start it. It touched me, and also touched my culture, tradition and my people. We have carried this burden too long'. The political maverick Apisai Tora also entered the fray, claiming in Parliament that the action of the NFP in the 1982 election was a show of arrogance (viavialevu) and insults heaped on the Fijian chiefs could only be made by people belonging to the lowest caste (kaisi bokola botoboto). Tora's passionate outburst however came as no surprise to many political observers who had closely followed his political career.

In 1977 he had hit out at the chiefly system in Fiji and said many Fijians were getting 'fed up' with the 'archaic' system, and that Fijian chiefs were using chiefly status to gain and keep power. He had also told another political rally in September 1977 that the Fijian chiefs were out to 'threaten' Indo-Fijians by indirectly telling people not to vote for the then leader of the NPF, Koya. 'Do not subjugate the future of Fiji in the hands of the power-hungry Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara. And whatever provocation people are under we do not want any violence in this (1977) election'.

It is not surprising therefore that a decade later the rightful place of the chiefs in the national life of the Fijians again became a burning issue when the Fiji Labour Party went into coalition with the Alliance Party's political arch rivals, the NFP. But it was also to herald the arrival of a military-cum civilian dictatorship following the two military coups in 1987. In fact, the writing was already on the walls, as a Fiji Sun editorial had feared shortly after the Bau meeting in 1982:

'The Great Council of Chiefs has passed an incredible resolution calling for a constitutional change which, if it occurred, would change Fiji overnight from a democracy to an autocracy, or even a dictatorship. It is a horrendous thought. For many years Fiji has been held up to the world as a multi-racial society which works-where two races with widely disparate religions, culture and ethnic backgrounds have lived and worked harmoniously for a hundred years. Now, with a stroke of a pen, a group of our most respected elders and statesmen are prepared to throw all that away and march backwards into the 19th Century and beyond.’

To be continued

Fiji's Daily Post, July 2000

The Fijian Commoners will be imprisoned by George Speight and Chiefs’ escapades: 'One dead, the other powerless to be born'.

The failed businessman turned rebel coup leader, George Speight, might have succeeded in ousting a democratically elected government and escaping criminal charges but in the process he and his henchmen have set back the progress and development of ordinary Fijian commoners.

In their crude racist submission to the Great Council of Chiefs, the group have once again silenced the voices of their ordinary fellowmen who seemed to have been coming out of the shadow of their chiefs. In stripping Mahendra Chaudhry of his political power, the group have, in fact, stripped the ordinary Fijian of his or her power.

For once again, it is the traditional chiefs who are being called upon to decide the fate of the Fijians and non-Fijians alike: the very role they were groomed to perform during Fiji’s turbulent history.

The Circus Showman and Educated Mule

In the old and dusty records of the British Colonial governors experiences, stored in the vaults of Rhodes House, the University of Oxford's library on Colonial and Imperial studies, I found the following letter to the Colonial Office in London from one of the many governors to Fiji, Sir George O' Brien. The letter, written from Government House in Suva, is dated the 14th of December 1897. The subject matter is Britain's policy of governing Fiji through the native chiefs. Governor O'Brien, who successfully argued against the federation of Fiji with New Zealand and Australia, wanted to express his mind on 'native policy' in a few words privately. And he did indeed, in a language which made me cringe on the first reading of his letter.

The Governor O’Brien’s Letter

The colonial governor O'Brien begins his letter by informing the Colonial Office that 'the situation in Fiji reminds one of nothing so much as the story of the circus showman & and his educated mule.' He continues the letter in the following vein: ''Ladies & gentlemen'', he (the showman) is reported to have said, ''you see before you a most remarkable animal - an educated mule. I have educated him myself. For the last 15 years I have done nothing but educate him. And the consequence is that I am in the proud position to-night, as I shall presently show you, of being able to make him do anything I like.'' Governor O'Brien continues:

'So with the Fiji Government and the Chiefs. After many years of governing Fiji through the chiefs we are able to make them do anything we like.'

It is not surprising, therefore, that some radical native Fijians have branded the chiefs as 'colonial or bureaucratic chiefs'. Others have accused them of being experts at political manipulation; they are fronts for big-time multi-national companies and commission agents, they promote racial hatred; they thwart every genuine move towards national cohesion and democracy; in short, theirs is, in many senses, a role actually subversive of the unity, progress and stability of this country. They have held back the economic, educational, and political progress of commoner Fijians. The very existence of these traditional rulers is inconsistent with the main goal of our struggles and efforts: building a united country, democracy, and a just, fair and stable political order.

Some claim that the Great Council of Chiefs, based as it is on inheritance, is not only thoroughly undemocratic, but most of those who man it are part of the tiny class of Fijians whose activities are some of the main causes of the country's racial problems. If democracy is to grow and flourish, its roots must be planted in a healthy, vibrant soil, and not on a murky and undemocratic foundation. The radical Fijians claim that at the grass-roots level, democratic structures, specifically democratically elected village, district, and local government councils and committees, manned by the elected representatives of the people should be established to decide matters of Fijian and national concern.

The defenders of the chiefs, on the other hand, have welcomed them as 'boundary-keepers' or mediators between different races who have used their authority and prestige, not to mention the strong weapon of coercion at their disposal, to stabilise crisis situations, and only to re-establish their chiefly control of Fiji.

Understandably, the deposed President and the paramount chief of Lau, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara was concerned with the way politicians played with the lives of his people during the last elections. Addressing a meeting of the Lau Provincial Council in Moala, Ratu Mara said these were evident in the statements made, in which chief's were insulted. In a sombre tone, the President and Tui Lau, Ratu Mara asked why statements such as 'don't elect your chiefs but elect a commoner because its easier to deal with them' were made to his people only. And according to Ratu Mara, the situation was worsened when the leader making those statements said nothing about other high chiefs from other provinces. He named numerous provinces whose high chiefs also contested the May elections.

Ratu Mara was referring to statement by the former Prime Minister and leader of the Soqosoqo ni Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT), Sitiveni Rabuka, now the chairman of the Great Council of Chiefs. The former PM had made such statements saying it is easier for the common people to approach commoner parliamentarians with their needs than it is to go to chiefs for help. Ratu Mara said he has been dwelling on the issue for quite sometime and has reminded his people, that those who are chosen to lead in government must always respect their chiefs. He asked the meeting to discuss ways in which all the chiefs in the province could support each other.

Traditional Authority in Colonial Era

British colonial rule was established following the Deed of Cession in 1874 whereby Fiji became a possession and dependency of the British Crown. In Ratu Seru Cakobau's words, the self-styled 'King of Fiji', the British were called upon to 'exercise a watchful control over the welfare of his children and people; and who, having survived the barbaric law and age, are now submitting themselves under Her Majesty's rule to civilization'. Of the several factors that had compelled the Fijian chiefs to pass their country to the British Crown, one was the menacing threat from the restless white settlers. Soon after the Deed of Cession the British government appointed the aristocratic Sir Arthur Gordon Hamilton (later Lord Stanmore), as the first Governor of Fiji.

The youngest son of the forth Earl of Aberdeen, in Scotland, Gordon, who had earlier ruled Trinidad (1886-70) and Mauritius (1870-74), arrived in Fiji with a reputation-although his true intentions have since been closely questioned-as 'an uncompromising guardian of native rights', and his influence can still be found in the land policies in Fiji. He also introduced a new ethnic group into Fiji-the indentured Indian labourers-in order to provide a work force for the colony's cane fields, while simultaneously safeguarding Fijian culture through the chiefs.

Consequently, the chiefs-Fiji's traditional rulers-were recognized by the British colonial government. Through the system of indirect rule, evolved by Lord Lugard in West Africa, and applied by his successors elsewhere, separate Fijian institutions were established to facilitate ruling them. These institutions, while creating a 'state within a state', gave the Fijian chiefs limited powers to rule their subjects, and to deeply influence the subsequent history of the colony. The objectives underlying Gordon's policies were similar to those which had given rise to colonial practices elsewhere: a divide and rule policy whereby the colonial government divided in order to rule what it integrated in order to exploit.

The partnership between the chiefs and Gordon not only enabled, according to the historian R. T. Robertson, 'the domination of the eastern chiefs particularly over the west, but it also resulted in the rise of a new type of bureaucratic chief, aware of the need to adjust to the demands of the colonial state if they were to achieve their class aims'. Others have written elsewhere that the ruling Fijian class had greatly benefited from colonial education, as the Council of Chiefs demanded that Fijian commoners should not receive education in the English language. The result was that very few Fijians, mostly of chiefly rank, entered the civil service as junior members of the 'bureaucratic bourgeoisie'. The white planters of the colonial era, however, condemned Gordon's native policy, and saw one of the most powerful chiefs in Fiji as only fit to be a white man's gardener. But the chiefs saw their roles through a different mirror-as guardians of the commoner Fijians.

It must be pointed out that the Deed of Cession was never universally accepted by Fijians, especially those of western and central Viti Levu. These people were the first to rebel against the colonial order, 'believing that it implied also domination by eastern chiefs who had signed the Deed of Cession'.

Chiefs in Post-Independent Fiji

When Fiji became an independent nation on 10 October 1970, it was the traditional eastern chiefs in the Alliance Party who took control of the nation's political leadership, with only two brief interruptions in 1977 and 1987. It was only in the recent elections that the chiefs found themselves not at the helm of government. The first high-profile challenge to chiefly rule came from one Apolosi Nawai [described as the Rasputin of the Pacific], who was banished to the island of Rotuma in 1917, 1930 and 1940 for portraying himself as the Messiah of the Fijian people. The demise of Nawai, however, failed to discourage other Fijians from taking up the challenge.

In the 1960s it was Apisai Tora who was in the forefront of western dissent against the eastern chiefs; in the 1980s it was Ratu Osea Gavidi and his Western United Front. But in 1973, the late Sakeasi Butadroka, a former Assistant Minister in the Alliance government, declared an all-out verbal war on Ratu Mara. The legitimacy of chiefly rule, based on traditional norms, faced an internal challenge. Butadroka himself is from a non-chiefly background and hails from Rewa province whose paramount chief is Adi Lady Lala Mara. But Butadroka described his dispute with Ratu Mara as a political one claiming that 'European politics and traditional matters are two different things'.

He went on to state that 'in traditional matters I greatly respect this man of noble birth and I have also reverence and try at all times do what is right'. Thus Butadroka (a man who had 'lost his senses', according to Ratu Mara) permanently revolutionized Fiji's politics, paving the way for other disgruntled Fijians to follow suit in the future. He had finally broken the tenuous thread of political tolerance for the chiefs, and the effects were to be felt in the future, especially during elections in Fiji.

In the 1987 general election, the Co-Deputy Prime Minister Dr Tupeni Baba, than the chief spokesman for the NFP/FLP Coalition, offered the following explanation as to why the Fijians were no longer going to elect people merely because they were chiefs: 'The Fijians have always viewed the Alliance as being the Fijian party. That base is being eroded. For the first time Fijians are being offered a list of credible Fijians standing against the Alliance. These Fijians can match the Alliance on its own front. They have comparable experience and now-how. For the first time there are Fijians who are willing to sacrifice their jobs and positions. Fijians will no longer elect people merely because they are chiefs.'

The Coalition seemed to have caught the Fijian people's imagination. The message to them was clear, as the late Prime Minister Dr Timoci Bavadra told one Fijian political gathering: 'There is a need to realize the difference between the traditional role and our democratic rights as citizens of this country.' He also called on the Alliance Party to stop employing abuse of Fijian tradition as a means of furthering its political ambitions. In a statement apparently directed at other Fijians caught in the traditional struggle, Bavadra made his position clear: 'I have great respect for both my great uncles, the Tui Vuda and the Taukei Nakelo in so far as the traditional chiefly system is concerned. But I beg to differ from both of them as far as political belief and standing are concerned…My loyalty to the Tui Vuda as chief of the Vanua is unshakable. But as far as my political affiliation is concerned I owe allegiance to my party. We belong to two different parties and we have different ideologies.' Moreover, the sorry state of the Fijian's plight must be blamed on the Alliance, for it was under the Alliance government that the Fijian remained in the economic backwater. The Alliance hit back with a vengeance.

Some leading Alliance candidates demonstrated the resurgence of Fijian nationalism in a bewildering variety of pronouncements. For example, Ratu David Tonganivalu warned that the Fijian chiefs must remain a force for moderation, balance and fair play against such extremism. He said the chiefs were a 'bulwark' of security for all and custodians of Fijian identity, land and culture. Ratu David, himself a high chief, said to remove chiefs would 'pave way for instability'. Ratu Mara also joined the political fray. Declaring that 'I will not yield to the vaulting ambitions of a power-crazy gang of amateurs-none of whom has run anything-not even a bingo', charged that there was an FLP ploy to destroy the chiefly system.

Dr Baba, speaking for FLP, denied these charges. He accused Ratu Mara and others of attempting to reverse the tide of history in order to prevent the old Fijian order from dying, saying it was a desperate bid by Ratu Mara to cling to power, and added that political manipulation of Fijian people's emotions on the eve of a general election devalued democratic leadership. Whether the Alliance was attempting to reverse the tide of history or not is questionable, but one thing is clear; history was not only repeating itself but had come full swing, except that the main players now were Fijian commoners versus the chiefs. In the past, it was the Indo-Fijian politicians who used to take the Fijian chiefs to task over political and traditional authority. The establishment and perpetuation of the separate Fijian Administration however made it extremely difficult for them to establish alternative bases of legitimacy.

The Chiefs and the Indians

The Indo-Fijians are all chiefs and no commoners. In the context of Fijian politics, therefore, their political leaders have always found themselves caught in the conflicting traditional, bureaucratic, and charismatic forms of authority in Fiji. The Indo-Fijian leaders had agreed to confer veto power to the chiefs in the Senate during the 1970 Constitutional Talks in London, which meant that for the first time in Fiji's history, the Great Council of Chiefs suddenly enjoyed its say in the mainstream of Fijian politics. In the old colonial days, much of what was deliberated was often decided in advance by judicious consultation between the chiefs and the colonial administrators.

Ironically, in post-independent Fiji it was the very Indo-Fijian leaders who attracted virulent criticism whenever they condemned the 'political chiefs' in the Alliance Party or their traditional institution-the Great Council of Chiefs.

In the 1982 general election the Indo-Fijian leaders were accused of collaborating with the infamous 'Four Corners' programme on elections in Fiji which claimed that the present leaders of Fiji were descendants of the Fijian chiefs who 'clubbed and ate their way to power'. But the most vicious attack on the Indo-Fijian leaders was made in the Senate where one Fijian senator, Inoke Tabua, stoutly defended Ratu Mara, his paramount chief. He warned: 'I want to make it clear in this House that whoever hates my chief, I hate him too. I do not want to make enemies but to a 'Kai Lau' like me, if someone is against my chief he is also against me and my family right to the grave.'

Tabua refused to isolate politics from chieftaincy. Understandably, as Ratu Mara himself had told the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the 1982 election that his evidence should be considered and treated in the light of his three main roles in Fiji: 'On the one hand I live, think and act as an ordinary citizen of this State and also as a chief in the Fijian traditional social system. I am also a politician and leader of the Alliance Party, which is closely interested in these proceedings. And, lastly, I am Prime Minister of this State and leader of its government.' It was these three roles that dominated the sentiments and minds of Fijians when it came to passing judgement on the actions of Indo-Fijian leaders during the general election. They invoked their traditional ties with their chiefs to condemn the Indo-Fijian leaders.

The Ra Provincial Council and the Great Council of Chiefs, through two resolutions, tried to reassure the Fijian people of their determination that Fijians should, and always would, rule Fiji. The first tentative step was taken during a meeting of the Ra Provincial Council which resolved that the offices of Governor-General and Prime Minister must be reserved for Fijians and that this should be the subject of constitutional changes, a demand first voiced by Butadroka's FNP in the 1970s.

The Council also proposed that the composition of the House of Representatives should be two-third Fijian and one-third all other races. The Council also resolved that the two resolutions be forwarded for inclusion on the agenda of the Great Council of Chiefs meeting scheduled for November 1982. Council members were of the opinion that the issues should be discussed at the Bau meeting, when the chiefs from the various traditional Fijian confederacies discussed issues of Fijian interests.

Both resolutions were condemned by the Western United Front (WUF) and the NFP, then in a Coalition pact for the 1982 election. The WUF expressed surprise that some Fijians still felt so strongly about the last general election and dismissed as totally unfounded the allegations that the Fijians and their traditional systems had thereby been insulted. WUF also considered that there was nothing derogatory in the 'Four Corners' programme. While linking the programme with the Alliance's involvement with the Carroll team, WUF's general-secretary said, 'Cannibalism was part of life in Fiji in the early days and we Fijians are descendants of cannibals. What is wrong with that? Only powerful chiefs in those days enjoyed on bokolas. I cannot find why some Fijians are annoyed about the Four Corners programme'.

The Great Council of Chiefs moved to endorse the two manifestly racist resolutions thus presenting itself in the eyes of the Indo-Fijian community as the political champion and promoter of Fijian nationalism, as preached by the FNP. The resolutions were finally passed despite the abstention from Ratu Mara and then Deputy Prime Minister, Ratu Penaia, who pointed out that to change the Fiji Constitution required the consent of a two-thirds majority in both Houses. The role of Ratu Mara, who abstained from voting, did nothing to allay Indo-Fijian fears. As an NFP/WUF Coalition statement later charged: 'It should be apparent even to a political novice that the whole exercise was carefully stage-managed to intimidate non-Fijians, especially Indians and the Fijian supporters of the Coalition'.

It also expressed surprise that Ratu Mara had abstained from voting rather than opposing the two resolutions. Ratu Mara replied angrily that he 'was is no way obligated to his political party to say what he did or said in the Council'. It was during the debate on the resolution that trade unionist Gavoka had likened Indo-Fijians to dogs; and Mrs Irene Jai Narayan, branding the Bau resolution as racist, went on to state: 'To liken Indians to dogs…is a grave and unwarranted provocation to the entire Indian community. It is now obvious that those indulging in the abuse of Indians are not reacting to any so-called insults…[but] because the NFP/WUF Coalition dared to challenge for power in the last general election and came within a whisker of wresting it from the Alliance.'

Mrs Narayan further observed: 'It is indeed curious that the controversial motion came up while the Prime Minister claims that the worst insults he received were from Fijians themselves, why the focus of attack and resolution adopted by the Great Council of Chiefs have been designed to rob of the few rights they (Indians) have left to live in the country of their birth.' Clearly, the statement continued, racial policies espoused by the FNP leader, the commoner Butadroka, had found greater favour with the chiefs than had the so-called multi-racial policies of the paramount chiefs leading the Alliance Party.

Another Fijian senator, Ratu Tevita Vakalalabure, warned that unless Indo-Fijians united with Fijians and if what happened in the 1982 general elections was repeated at the next, probably 1987 election, 'Blood will flow, whether you like it or not. I can still start it. It touched me, and also touched my culture, tradition and my people. We have carried this burden too long'. The political maverick Apisai Tora also entered the fray, claiming in Parliament that the action of the NFP in the 1982 election was a show of arrogance (viavialevu) and insults heaped on the Fijian chiefs could only be made by people belonging to the lowest caste (kaisi bokola botoboto). Tora's passionate outburst however came as no surprise to many political observers who had closely followed his political career.

In 1977 he had hit out at the chiefly system in Fiji and said many Fijians were getting 'fed up' with the 'archaic' system, and that Fijian chiefs were using chiefly status to gain and keep power. He had also told another political rally in September 1977 that the Fijian chiefs were out to 'threaten' Indo-Fijians by indirectly telling people not to vote for the then leader of the NPF, Koya. 'Do not subjugate the future of Fiji in the hands of the power-hungry Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara. And whatever provocation people are under we do not want any violence in this (1977) election'.

It is not surprising therefore that a decade later the rightful place of the chiefs in the national life of the Fijians again became a burning issue when the Fiji Labour Party went into coalition with the Alliance Party's political arch rivals, the NFP. But it was also to herald the arrival of a military-cum civilian dictatorship following the two military coups in 1987. In fact, the writing was already on the walls, as a Fiji Sun editorial had feared shortly after the Bau meeting in 1982:

'The Great Council of Chiefs has passed an incredible resolution calling for a constitutional change which, if it occurred, would change Fiji overnight from a democracy to an autocracy, or even a dictatorship. It is a horrendous thought. For many years Fiji has been held up to the world as a multi-racial society which works-where two races with widely disparate religions, culture and ethnic backgrounds have lived and worked harmoniously for a hundred years. Now, with a stroke of a pen, a group of our most respected elders and statesmen are prepared to throw all that away and march backwards into the 19th Century and beyond.’

To be continued