"Unlike the independence [1970] constitution, which was a negotiated document, the 1990 constitution was basically imposed on the people and in the face of the unanimous opposition of one major community, the Indo-Fijians, along with considerable opposition from others...

While native institutions intruded upon the constitutional scheme, the 1990 constitution was not allowed to impose its discipline over them. For example, the acts of the GCC were excluded from the purview of the ombudsman, an office established by the 1970 Constitution. Not accountable to any institution or process, the GCC was now effectively above the law...the indigenous institutions had been largely freed of constitutional supervision; many of the native institutions had been so recomposed and manipulated they could no longer be regarded as indigenous but, rather, as instruments of those Fijians who controlled the state."

Professor Yash Ghai and Jill Cottrell, 2007

We publish below an excerpt from Professor Yash Ghai and Jill Cotlrell's "A tale of three constitutions: Ethnicity and politics in Fiji", International Journal of Constitutional Law, Volume 5, Issue 4, 1 October 2007, focusing on the 1990 RACIST Constitution that was imposed on us!

Space does not allow for a detailed examination of the 1990 constitution, which functioned as a bridge between the 1970 and 1997 constitutions—a reaction to the former, it triggered a crisis that gave rise to a search for new values that find expression in the latter.

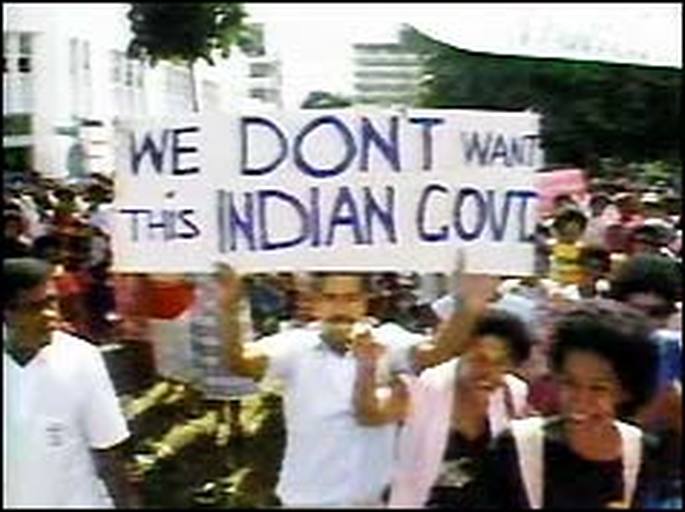

Unlike the independence constitution, which was a negotiated document, the 1990 constitution was basically imposed on the people and in the face of the unanimous opposition of one major community, the Indo-Fijians, along with considerable opposition from others.

The new constitution rejected multiracialism in favor of Fijian dominance and attempted to close constitutional loopholes that might have frustrated the goal of ensuring Fijian supremacy for all time. It reinforced the segregation of races and the political subordination of Indo-Fijians. Finally, it aimed at the enhanced dominance of purely Fijian institutions over the state. In what follows we summarize some of the features of this constitution.

The new constitution retained the parliamentary system of government and a bicameral legislature, though with significant changes meant to guarantee Fijian dominance. No cross-voting seats were provided for, so all representation became communal. In the seventy-member House of Representatives, thirty-seven seats were reserved for Fijians; this meant that they would not need to make alliances with any other community in order to form a government. Other Pacific islanders, who previously had appeared in the electoral roll of Fijians, were reclassified as so-called “general” electors.

The registration of all Fijian voters was now tied to the traditional rules of descent for each subordinate communal group within Fijian society; final decisions were left to the Native Land Commission (which also affected land rights).

This led to some separation of traditional groups within the Fijian community, a tendency that was further reinforced by making the provinces the basis for Fijian constituencies. In the allocation of seats, there was also discrimination against urban Fijians, who were assumed to be less strongly bound by communal ties than rural people.

The Senate consisted of twenty-four members nominated by the GCC, one by the Rotuman Council, and nine members nominated by the president of Fiji to represent other communities (without any requirement for consultations). The president himself was to be appointed by the GCC and would presumably be a Fijian, although this was not specified in the text as a qualification. This over representation of Fijians, when they also had an absolute majority in the other house, belied the justification for the second chamber.

In addition, the 1990 constitution enhanced the entrenchment of legislation protecting Fijian land and other interests. And the protection given to these specific acts was now extended to any bill “which affects land, customs or customary rights.” Amendments required the support of not less than eighteen of the twenty-four Senate members appointed by the GCC. The 1990 constitution also changed the rule whereby minerals belonged to the state. Now minerals were vested in the owners of the land where they were found—potentially, a major shift of resources from the state to the one community that owned most of the land.

Provision was made to guarantee a Fijian administration: only a Fijian could be prime minister. Because the president had to appoint to this office a person who commanded the support of a majority in the House, the implicit assumption was that there would always be a clear Fijian majority bloc. This constitution gave even more power to the executive than the 1970 text had, since the moderating role of the leader of the opposition (a post traditionally held by an Indo-Fijian) was much diminished, and the prime minister was given a direct and decisive say in appointments to various offices. The chairman and one other member of the three-member Police Service Commission had to be Fijian —an arrangement clearly designed to establish dominance over the police, in which institution there had previously been racial parity. Further, the legislature and the executive were given unlimited powers to establish programs and policies for “promoting and safeguarding the economic, social, educational, cultural, traditional and other interests of the Fijian and Rotuman people.”

The 1990 constitution enhanced the role of indigenous institutions. It gave special status to Fijian customary law, which also increased the separation of Fijians from the other communities. In its proceedings, Parliament had to take into account the application of this customary law and had to have a “particular regard to the customs, traditions, usages, values and aspirations of the Fijian people.” Native Fijian courts had to be revived. The interpretation of native customs, traditions, and usages (including land rights) and the determination as to the existence, extent, or application of customary laws were to be made by the Native Lands Commission. Customary laws were freed from the application of the right to equality.

While native institutions intruded upon the constitutional scheme, the 1990 constitution was not allowed to impose its discipline over them. For example, the acts of the GCC were excluded from the purview of the ombudsman, an office established by the 1970 Constitution. Not accountable to any institution or process, the GCC was now effectively above the law. It was also placed beyond criticism, as Parliament was authorized to curb freedom of expression in order to protect “the reputation, dignity and esteem of institutions and values of the Fijian people, in particular the Bose Levu Vakaturaga [Great Council of Chiefs] and the traditional Fijian system and titles or reputation, dignity and esteem of other races in Fiji, in particular their traditional systems.”

The ombudsman was also prevented from reviewing the actions of the Native Land Commission, the Native Fisheries Commission, and the Native Lands Trust Board. Similarly, many of these decisions, especially those made by the Native Lands Commission, were removed from the jurisdiction of the courts.

On the one hand, the indigenous institutions had been largely freed of constitutional supervision; on the other, however, many of the native institutions had been so recomposed and manipulated they could no longer be regarded as indigenous but, rather, as instruments of those Fijians who controlled the state. This is evident in the way in which the leaders of the coup changed the membership of the GCC to exclude the supporters of the democratically elected government they overthrew, thereby increasing their own power to nominate members.

Another consequence was that the close control of the state by the native institutions prevented other races from influencing the state's policies and undermined the capacity or willingness of the state to promote interethnic bargaining and accommodation.

Predictably, the weakening of institutions of accountability facilitated corruption and impropriety in public life and produced an inefficient government. This state of affairs led to a major crisis of confidence in the future of Fiji and to the emigration of a substantial number of talented citizens. The situation that emerged was perceived as a principal cause of the stagnation of the economy, retarding the social and economic advancement of all the communities; was much criticized abroad; and, finally, secured Fiji's expulsion from the Commonwealth.

Most importantly, the new constitution reinforced internal divisions among Fijians. Once Indo-Fijians were sidelined, there was little to maintain the political unity of Fijians. The passing of power to commoners undermined the chiefly class, which had sedulously cultivated both the ideology of traditionalism and a sort of unity under eastern hegemony. Given the resultant multiplicity of parties among Fijians, no one party could form a government without the support of an Indian party.

Needing that support, Rabuka agreed to a speedy review of the constitution, in accordance with a provision for a review at the end of seven years.

Conclusion:

The self-proclaimed mission of the 2006 coup maker is to resolve this ambiguity (consociation and the political integration of different communities) in favor of integration. In a recent statement by the new government, which calls itself the interim government, it announced plans for the review of the 1997 Constitution with the goal of “rid[ding] the Constitution of provisions that facilitate and exacerbate the politics of race [in] such areas as the registration of voters and the election of representatives to the House of Representatives through separate racial electoral rolls.”

The government claims to advocate the abolition of voting in “terms of racial classifications,” so that “each voter should vote for a candidate of his/her choice in a common roll, with each vote having equal value.”

If this is achieved, the pendulum will have swung to the opposite extreme from past preoccupations with race.

And Fiji's fortunes may then tell us something more about the relative merits of consociation and integration.