"As we have already said, the publication attributed to the applicant, had nothing to do with any proceedings in the National Assembly and was made outside Parliament. This appeal is therefore devoid of any merit." - Zambia Supreme Court, 2003

Aiyaz Khaiyum's motion for a vote in Fiji's Parliament that:

- 1) Hon. Ratu Naiqama Lalabalavu be cited for a serious breach of privilege and contempt of Parliament

- 2) that the matter be now referred to the Privileges Committee under Standing Order 134(2)(b) to determine the type of sanction for the breach and;

- 3) that the Privileges Committee must meet today 18 May 2015, and provide its recommendations to Parliament at the latest by Thursday 21 May 2015 as to what sanctions should be imposed by Parliament against Honourable Lalabalavu, after which such action as deemed appropriate by Parliament shall be taken

“SOMETIMES coups can bring positive changes..This Calls for all political players to be level headed so that we can have dialogue for all...Unless this is done, it is unlikely that in this country

things like this will stop.” -

National Party Secretary General and Zambian lawyer Ludwig Sondashi

Zambian Supreme Court, 2003 re Ludwig Sondashi, MP -

Contempt of Parliament for words uttered outside Parliament:

1. Holdings or forming of an opinion by a member of Parliament which opinion has nothing to do with the proceedings in Parliament or National Assembly does not amount to contempt of the National Assembly or Parliament and cannot warrant disciplinary action against a member of Parliament holding such opinion.

2. The Oath of allegiance taken by members of Parliament does not stand against holding or forming of opinions by members of Parliament and does not fetter their freedom of expression.

SUPREME COURT SAKALA, CJ., CHIBESAKUNDA AND SILOMBA JJS

5TH NOVEMBER, 2002 AND 13TH MAY, 2003.

SCZ No. 6 OF 2003

Flynote:

Constitutional law – Administrative law – Judicial Review – National Assembly Powers and Privileges – Whether breach of oath of allegiance was committed – Parliamentary rules and disciplinary procedure.

Headnote:

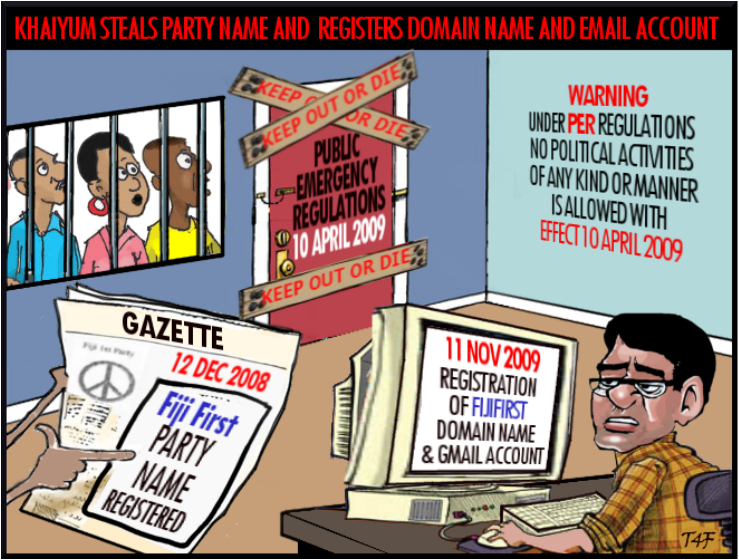

Following a failed coup de’tat in 1997 in Zambia Ludwig Sondashi who was a member of Parliament expressed his opinion to a newspaper in an interview that he felt sometimes coups could bring positive changes to a Nation. This was said outside parliament in his individual capacity. Upon the Newspaper publishing what Ludwig Sondashi had said, the National Assembly took disciplinary action against him.

He applied for Judicial Review to have that decision of the National Assembly quashed. Judgment was entered in favour of Ludwig Sondashi and the decision of the National Assembly was quashed. The Attorney-General and the Speaker of the National Assembly appealed against that High Court decision.

HELD:

1. Holdings or forming of an opinion by an opinion by a member of Parliament which opinion has nothing o do with the proceedings in parliament or National Assembly does not amount to contempt of the National Assembly or parliament and cannot warrant disciplinary action against a member of parliament holding such opinion.

2. The Oath of allegiance taken by members of parliament does not stand against holding or forming of opinions by members of parliament and does not fetter their freedom of expression.

For the Appellants : Mr. M. Haimbe, Senior State Advocate

For the Respondent : Mr. S. Chisulo of Sam Chisulo and Company

JUDGMENT

For convenience, we shall refer to the Appellants as the first and second Respondents and to the Respondent as the Applicant, which designations they were in the court below.

This is an appeal against a Judgment of the High Court granting the Applicant a declaration that the decision, made by the National Assembly to suspend him from sittings of the House and enjoying the privileges and benefits of his office, including the payment of his personal emoluments and sitting allowances, with-held without lawful grounds, was null and void.

The facts and circumstances leading to the appeal are very brief. The Applicant was elected on the National Party ticket as a Member of Parliament for the Solwezi Central Constituency in November, 1996. Immediately after the 28th of October, 1997 coup d’etat, he was interviewed by a Post Newspaper Reporter whether coups could bring positive changes in the country. He responded by saying that coups can sometimes bring positive changes basing upon his observations of experiences in other countries. On 29th October, 1997, the Post Newspaper published an article based on the interview. The article was captioned:- “COUPS CAN BE POSITIVE, SAYS SONDASHI.” Under the caption, the following was published:-

“SOMETIMES coups can bring positive changes, National Party Secretary General Ludwig Sondashi said in an interview yesterday.

Sondashi who is also Solwezi Central Member of Parliament and a Prominent Lusaka Lawyer, answering a question whether the coup would have been preferable to the rule of the MMD Government, said the attempted coup by Capt. Steven Lungu, alias Capt Solo is a sign that all is not well in the Country and people should not pretend otherwise.

“This Calls for all political players to be level headed so that we can have dialogue for all” Sondashi said “Unless this is done, it is unlikely that in this country things like this will stop.”

He said burning issues that have aggrieved most people in Zambia are the Nikuv register and the issue of government funding opposition parties should be addressed.

“Everybody knows that the talks will be mishandled. No one wants coup d’etats,” Sondashi said in reference to President Chiluba’s national address on both television and radio reassuring people that his government will continue to talk.”

On 21st November, 1997, the then Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Valentine Kayope, raised a point of order in Parliament in relation to the article. On 25th November, 1997, the Hon. Deputy Speaker made a ruling to the effect that a prima facie case of breach of oath of allegiance had been made against the Applicant: The Hon. Deputy Speaker then referred the matter to the Standing Orders Committee for consideration and action. The Standing Orders Committee subsequently made a decision suspending the Applicant from sitting in Parliament and from enjoyment of all the privileges attaching to the office of Member of Parliament including suspension of all emoluments and allowances for a period of four months effective from 1st December, 1997 to end of March, 1998.

The Applicant, aggrieved by the decision taken, applied for leave to apply for Judicial Review seeking for the following reliefs:

(a) An Order of Certiorari and or Mandamus to remove into the High Court for the purpose of quashing the decision of the National Assembly whereby it was decided on 1st December, 1997 that the Applicant be suspended from sitting of the House and from enjoying his rights and privileges of the House including the payment of his personal emoluments and allowances;

(b) Further or alternatively that the decision of the National Assembly to suspend the Applicant is null and void, is of no effect as it was made in bad faith, in excess of the powers and in contravention of Articles 20, 64, 65 and 71 of the Constitution of Zambia and Section 19 and 28 of the National Assembly (Powers and Privileges) Act, Cap. 12 of the Laws of Zambia.

The grounds upon which the reliefs were sought are:-

that the decision of the National Assembly was manifestly a clear abuse of power as it was made in bad faith and in total disregard of the Constitution and Statutory Provisions of Cap. 12 of the Laws of Zambia;

that the Deputy Speaker, the Standing Orders Committee and the National Assembly did not take into account relevant considerations;

that what the applicant said was an expression of political opinion, as such, he was protected by Article 20 of the Constitution of Zambia;

that the National Assembly does not have powers, as per the enabling Act, Cap. 12, to penalize the Applicant on the purported offence of “oath of allegiance; that according to Section 28 of Cap. 12, the maximum penalty which the House can impose upon a Member of Parliament who has committed an offence of Contempt of the Assembly, cannot be longer than the last day of the next sitting of Parliament of the Session in which the resolution to suspend a Member is passed; and that the National Assembly took into account irrelevant considerations.

The application was supported by an affidavit sworn by the applicant. There was also an affidavit in opposition sworn by the Principal Clerk of Journals.

The learned trial judge considered the affidavit evidence and the submissions. The court observed that when the question of violation of a constitutional provision arises, it is of no legal consequence to show that such was in good faith nor is it necessary to prove bad faith. The court found that the Speaker was properly joined as a party to the action. The court found that the application fell under Article 20 of the Constitution of Zambia, raising two issues for determination, namely

Whether the applicant’s freedom of expression under the Article was contravened; and Whether, if the answer to the first question was in the affirmative, the court had jurisdiction to grant the reliefs sought.

The learned Judge considered the issue of jurisdiction at great length. After setting out Articles 28(1), enforcement of protective provisions, Article 20(1), protection of freedom of expression, and Article 87, privileges and immunities of the National Assembly; the learned trial judge observed that in the United Kingdom, the High Court would most likely have held that it lacked jurisdiction in an application for judicial review of a decision of Parliament. After examining the provisions in the Indian Constitution, which specifically exclude the jurisdiction of the court to proceedings in Parliament; the learned trial judge accepted that the Indian High Court, has by constitutional provisions, no jurisdiction in the applications as the one before the court. The learned judge pointed out that there was no comparable provisions in our Constitution to the provisions in the Indian Constitution. The court concluded, on the issue of jurisdiction, that the High Court of Zambia has constitutional jurisdiction to hear applications for Judicial review in matters involving Parliament.

On the merits of the application, the court examined the article attributed to the applicant. The court observed that the article took the form of a comment or the applicant’s opinion, pointing out that the opinion may have been ill timed or lacked a realistic assessment of the realities of the time.

The court observed and emphasized that it was significant that the applicant made his comments outside the House; but that had these comments been made within the four walls of the House, the situation would have put on an entirely different complexion. The court pointed out that Article 20 of the Constitution provides for freedom of expression. The court held that the action taken in the House against the applicant, if allowed to stand, would have the negative effect of curtailing the applicant’s freedom of expression and would not know when he might offend Parliament. The court concluded that the applicant’s rights under Article 20 of the Constitution were violated when he was suspended.

The court granted the application and entered Judgment in favour of the applicant by awarding him pecuniary rewards which he would have received had he not been suspended. Interest at 50 percent was awarded to run from the date when the earnings were due. Each party was ordered to pay its own costs. Hence the appeal before us

In the written heads of argument supplemented by oral submissions, Mr. Haimbe advanced one detailed ground of appeal that the learned Judge erred and misdirected himself in law and infact when he held that the decision of the Speaker curtailed the applicant’s freedom of expression as he had uttered the offending statement outside the National Assembly; thereby falling into grave error when he failed to appreciate the significance of the Oath of Allegiance subscribed to by Members of Parliament and that it is a constitutionally permissible derogation of the freedom of expression of a Member of Parliament.

Mr. Haimbe contended that the applicant was not an ordinary citizen of this country but a duly elected Member of Parliament whose rights are fettered by the National Assembly (Powers and Privileges) Act, Cap. 12. According to counsel, the official Oaths Act as read together with Article 89 of the Constitution, relating to Oaths to be taken by the Speaker and the Members, make it mandatory for every member of the National Assembly on assuming office to subscribe to the Oath of allegiance.

Mr. Haimbe, however, conceded that Article 20 of the Constitution provides for the protection of freedom of expression, which included freedom to hold opinions without interference and freedom to impart and communicate ideas and information without interference. But he contended that the freedom enshrined in Article 20 is not absolute as clause 3 of the same Article provides for derogations which fetter the right on grounds of public safety, defence or public order. We heard further arguments that the Speaker of the National Assembly properly exercised his powers in censuring the applicant as section 28 of the National Assembly (Powers and Privileges) Act, Cap. 12, provides that where a member commits any contempt of the Assembly whether specified in Section 19 or otherwise, the Assembly may, by resolution either direct the Speaker to reprimand such a member or suspend him from the service of the National Assembly. It was submitted that Section 19 of Cap. 12 does not limit the jurisdiction of the Speaker to contempt committed by members within the precincts of the National Assembly as the inclusion of the words “otherwise” in the section extends the jurisdiction of the National Assembly to any contempt committed outside the House.

It was argued that the finding of the trial Judge that the applicant uttered the offending words in the article outside the national Assembly and that he was merely expressing his freedom of expression was a serious misconception of the law and a total failure to appreciate the significance of the Oath as a Member of Parliament does not cease to be bound by his oath even when Parliament is not is session. He is bound through out the tenure of his office; and the obligation is not severable or capable of being apportioned into segments as contended.

Mr. Chisulo, in response, also relied on written heads of argument supplemented by oral arguments. He submitted that the learned trial Judge was on firm ground in holding that the decision of the Speaker curtailed the applicant’s freedom of expression as the statement was uttered outside the National Assembly. Mr. Chisulo further submitted that the learned Judge did not fall into error by not recognizing the role of the Oath of Allegiance subscribed to by Members of Parliament as it was irrelevant and not a constitutionally permissible derogation of the freedom of expression of a Member of Parliament. Counsel pointed out that the National Assembly (Powers and Privileges) Act, Cap 12. of the Laws of Zambia does not fetter Members of Parliament’s rights of freedom of speech but enhances it.

We also heard arguments by Mr. Chisulo that the Oath of Allegiance subscribed to by a Member of Parliament is symbolic and a statement of intent. And for that reason, the Oath Act Cap 5, does not provide for penalties for its breach by Members of Parliament. It was submitted that subscription to the oath cannot act against the forming up of opinions by Members of Parliament. It was also submitted that the Oath subscribed to by Members of Parliament cannot be a proviso to freedom of expression in Article 20(3)(c) of the Constitution as a statement of oaths does not relate to freedom of expression.

It was contended that the statement made by the applicant, though unpalatable, was actually a statement of opinion enjoying the protection of Article 20 of the Constitution and therefore that no Member of Parliament can be disciplined for a statement made outside the House unless it was a contempt of the House or the Speaker. Counsel submitted that the Speaker acted in excess of his powers as the applicant committed no contempt.

We have very anxiously considered the Judgment of the court below and the submissions by both learned counsel. This appeal, as we see it, raises the simple but difficult question of a Member of Parliament’s right of freedom of speech outside Parliament on matters in no way connected with any proceedings in Parliament

We agree with the learned trial judge that the publication, attributed to the applicant and not denied, was ill-timed and lacked a realistic assessment of the realities of the time. But we also agree with the learned trial Judge that, it still was an opinion on the events of the time; nothing to do nor connected with any proceedings in Parliament. We also agree with the trial court that the fact that the comments were made outside the House was significant. Article 20(1) of the Constitution on protection of freedom provides as follows:-

(1) Except with his own consent, a person shall not be hindered in the enjoyment of his freedom of expression, that is to say, freedom to hold opinions without interference, freedom to receive ideas and information without interference, freedom to impart and communicate ideas and information without interference, whether the communication be to the public generally or to any person or class of persons, and freedom from interference with his correspondenc

Article 89 which provides for the taking of oaths by the Speaker and Members states:

The Speaker of the National Assembly, before assuming the duties of his office, and every Member of the National Assembly before taking his seat therein, shall take and subscribe before the National Assembly to the oath of allegiance.

The oath of allegiance taken and subscribed to is couched as follows:-

“I...........do swear that I will be faithful and bear allegiance to the President of the Republic of Zambia, and that I will preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of Zambia, as by law established.”

According to Mr. Haimbe, the oath of allegiance is one of the derogations envisaged by Article 20. We have examined the derogations in article 20. These are contained in article 20(2)(3)(a)(b)(c). They state as follows:

(2) Subject to the provisions of this Constitution a law shall not make any provision that derogates from freedom of the press.

(3) Nothing contained in or done under the authority or any law shall be held to be inconsistent with or in contravention of this Article to the extent that it is shown that the law in question makes provi

(a) that is reasonable required in the interests or defence, public safety, public order, public morality or public health; or

(b) that is reasonable required for the purpose of protecting the reputations, rights and freedoms of other persons or the private lives or persons concerned in legal proceedings, preventing the disclosure or information received in confidence, maintaining the authority and independence of the courts, regulating educational institutions in the interests of persons receiving instructions therein, or the registration of, or regulating the technical administration or the technical operation of, newspaper and other publications, telephony, telegraphy, posts, wireless broadcasting or television; or

(c) that imposes restrictions upon public officers;

In our view, it is not only overstretching those provisions by including the taking of Oath but exaggerating them. It was counsel’s contention that the applicant was bound by the oath of allegiance at all times, that the publication attributed to him, whether within the precincts of Parliament or not, was contempt of the House warranting the suspension of the applicant. We have difficulties to accept these arguments.

The arguments, attractive as they sound, cannot be tenable. We are not prepared to accept that the oath of allegiance taken, subscribed to by Members of Parliament, entails a derogation of their freedom of speech outside Parliament. We agree with Mr. Chisulo that the taking of an oath cannot be against forming of opinions by Members of Parliament. Above all, the publication attributed to the applicant had nothing to do with any proceedings in Parliament and was made outside Parliament.

We have examined Section 19 of the National Assembly (Powers and Privileges) Act Cap 12, which sets out the contempts which may be committed against the House. The contempts set out have all reference to the proceedings of the National Assembly or of a Committee of the Assembly or to any such person presiding at such proceedings. As we have already said, the publication attributed to the applicant, had nothing to do with any proceedings in the National Assembly.

This appeal is therefore devoid of any merit. It is dismissed with costs to be taxed in default of any agreement.