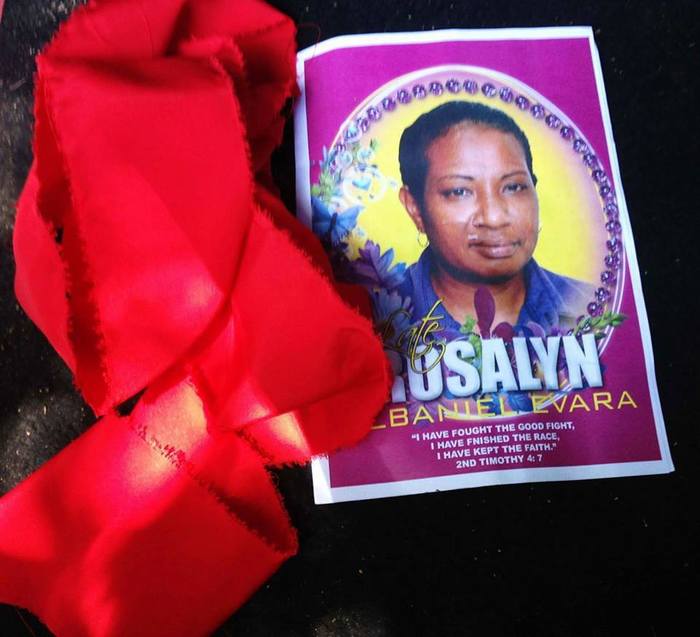

Rosalyn Evara gazes into the camera with her head resting on her hand.

Rosalyn Evara gazes into the camera with her head resting on her hand. The death of a high-profile Papua New Guinean journalist at the age of 41 has sparked a national debate about the country’s continuing epidemic of violence against women, after graphic photographs were shown at her funeral.

Family members of Rosalyn Albaniel Evara, who was an editor at PNG’s largest newspaper, have received support from the Port Moresby governor for their calls for a police investigation into her death.

Evara died last week after she collapsed at her Port Moresby home, and was rushed to hospital. The Post-Courier journalist was farewelled at a funeral in Port Moresby on Monday, where an aunt, Mary Albaniel, used her eulogy to allege Evara had been violently assaulted.

Albaniel, wearing a “say no to violence” T-shirt, showed photographs of her battered body and alleged a history of abuse.

“When I heard that you died, I regretted that I should have done more than just talk to you, but how?” said Albaniel.

She said they discovered the bruises when preparing Evara’s body, and decided to take photos in the hope it may lead to criminal prosecution.

Albaniel told the Guardian she felt compelled to raise the allegations at the funeral, which was attended by Evara’s husband.

“I’m using the same surname as the deceased’s maiden name. To continue advocating in my job as a defender of human rights would be useless if I can’t get justice done,” she said.

“I strongly advocate against all forms of violence against women. That’s why I decided to wear my job cap yesterday.”

On Tuesday morning the Port Moresby governor, Powes Parkop, reportedly ordered the woman’s burial be deferred for a postmortem and investigation, overriding the initial wishes of Evara’s mother, who later that day decided to formally request a postmortem.

Parkop has spoken out against gender-based violence in the past, and Albaniel is a human rights and anti-violence against women campaigner.

“It’s not only in PNG. I know from my job [the attention on Evara’s death] will make a big difference, and a big step forward [in addressing gender-based violence]. Because women don’t get the full support from the men, even their own husbands and brothers,” she said.

“Men don’t understand what it means to allow justice to prevail. There is a lot of fear. I told her family and I tell the public that I am advocating against it.”

Papua New Guinea is considered to be one of the worst places in the world for violence against women and girls. Earlier this year Human Rights Watch reported little had changed, despite public promises of reform by the government.

Human Rights Watch said police and prosecutors rarely prosecuted cases against perpetrators of family violence, and the government was still yet to act on family protection legislation passed in 2013.

Evara is survived by a daughter. According to reports, two of her children had died in the past two years.

The allegations raised at Evara’s funeral received national media attention, albeit little from her former workplace.

A former editor of the Post-Courier, Alexander Rheeney, accused the paper of failing in its duty of care and failing to seek justice for Evara. He said the Post-Courier, which is owned by News Corp, belittled her death by running a story on page 16, compared with the front-page treatment given by rival paper, the National.

“Your [gender-based violence] campaigns are worthless if you cannot effect change and become champions of change by starting in your own backyard,” Rheeney said.

The Boroko police commander, Titus Bayagau, confirmed to the Guardian there was now a police investigation.

Todagia Kelola, an editor at the Post-Courier, defended the news coverage of Evara’s death.

Kelola said he had been closely involved with the family, assisting with the funeral and other arrangements, as well as mourning the loss of a colleague. He said her death had come as a shock, and he had urged the family to have a postmortem done but respected their initial wishes.

He said the paper couldn’t report the allegations raised as they were unsubstantiated without a postmortem.

“Because there was no postmortem carried out, how can I say it was a GBV case?” he said.

Asked why he had not run a front-page report like the National, Kelola said he had wanted a report to focus on Evara.

“It really hurt me because I know if I was on the outside, the story by the National was telling a really good angle. But I was more concerned to bring out the life of Rosalyn when she had arrived in the Post-Courier, and as a journalist in PNG.”

He said he was glad the family had changed their minds and was requesting a full investigation.

“I can assure you that if it’s what has been stated we will aggressively go with it. When she was alive she never told us,” he said.

In an unbylined statement, the Post-Courier rejected a “tirade of accusations” which it said “sarcastically berated and belittled Post-Courier as a leading advocator against GBV and allegedly doing nothing to stop the treatment of a passed colleague from being one such victim”.

“We have never deviated at any one time in our stated commitment as a publishing entity to be included in the fight against gender-based violence,” it said.

“Through our factual reports and news stories, law enforcement agencies and taskforces have seriously reacted and responded to many specific and referred cases we have highlighted. And indeed there have been measurable successes for many of the victims of GBV, their families, parents and siblings.” The Guardian, October 2017

Family members of Rosalyn Albaniel Evara, who was an editor at PNG’s largest newspaper, have received support from the Port Moresby governor for their calls for a police investigation into her death.

Evara died last week after she collapsed at her Port Moresby home, and was rushed to hospital. The Post-Courier journalist was farewelled at a funeral in Port Moresby on Monday, where an aunt, Mary Albaniel, used her eulogy to allege Evara had been violently assaulted.

Albaniel, wearing a “say no to violence” T-shirt, showed photographs of her battered body and alleged a history of abuse.

“When I heard that you died, I regretted that I should have done more than just talk to you, but how?” said Albaniel.

She said they discovered the bruises when preparing Evara’s body, and decided to take photos in the hope it may lead to criminal prosecution.

Albaniel told the Guardian she felt compelled to raise the allegations at the funeral, which was attended by Evara’s husband.

“I’m using the same surname as the deceased’s maiden name. To continue advocating in my job as a defender of human rights would be useless if I can’t get justice done,” she said.

“I strongly advocate against all forms of violence against women. That’s why I decided to wear my job cap yesterday.”

On Tuesday morning the Port Moresby governor, Powes Parkop, reportedly ordered the woman’s burial be deferred for a postmortem and investigation, overriding the initial wishes of Evara’s mother, who later that day decided to formally request a postmortem.

Parkop has spoken out against gender-based violence in the past, and Albaniel is a human rights and anti-violence against women campaigner.

“It’s not only in PNG. I know from my job [the attention on Evara’s death] will make a big difference, and a big step forward [in addressing gender-based violence]. Because women don’t get the full support from the men, even their own husbands and brothers,” she said.

“Men don’t understand what it means to allow justice to prevail. There is a lot of fear. I told her family and I tell the public that I am advocating against it.”

Papua New Guinea is considered to be one of the worst places in the world for violence against women and girls. Earlier this year Human Rights Watch reported little had changed, despite public promises of reform by the government.

Human Rights Watch said police and prosecutors rarely prosecuted cases against perpetrators of family violence, and the government was still yet to act on family protection legislation passed in 2013.

Evara is survived by a daughter. According to reports, two of her children had died in the past two years.

The allegations raised at Evara’s funeral received national media attention, albeit little from her former workplace.

A former editor of the Post-Courier, Alexander Rheeney, accused the paper of failing in its duty of care and failing to seek justice for Evara. He said the Post-Courier, which is owned by News Corp, belittled her death by running a story on page 16, compared with the front-page treatment given by rival paper, the National.

“Your [gender-based violence] campaigns are worthless if you cannot effect change and become champions of change by starting in your own backyard,” Rheeney said.

The Boroko police commander, Titus Bayagau, confirmed to the Guardian there was now a police investigation.

Todagia Kelola, an editor at the Post-Courier, defended the news coverage of Evara’s death.

Kelola said he had been closely involved with the family, assisting with the funeral and other arrangements, as well as mourning the loss of a colleague. He said her death had come as a shock, and he had urged the family to have a postmortem done but respected their initial wishes.

He said the paper couldn’t report the allegations raised as they were unsubstantiated without a postmortem.

“Because there was no postmortem carried out, how can I say it was a GBV case?” he said.

Asked why he had not run a front-page report like the National, Kelola said he had wanted a report to focus on Evara.

“It really hurt me because I know if I was on the outside, the story by the National was telling a really good angle. But I was more concerned to bring out the life of Rosalyn when she had arrived in the Post-Courier, and as a journalist in PNG.”

He said he was glad the family had changed their minds and was requesting a full investigation.

“I can assure you that if it’s what has been stated we will aggressively go with it. When she was alive she never told us,” he said.

In an unbylined statement, the Post-Courier rejected a “tirade of accusations” which it said “sarcastically berated and belittled Post-Courier as a leading advocator against GBV and allegedly doing nothing to stop the treatment of a passed colleague from being one such victim”.

“We have never deviated at any one time in our stated commitment as a publishing entity to be included in the fight against gender-based violence,” it said.

“Through our factual reports and news stories, law enforcement agencies and taskforces have seriously reacted and responded to many specific and referred cases we have highlighted. And indeed there have been measurable successes for many of the victims of GBV, their families, parents and siblings.” The Guardian, October 2017

The (not so) mysterious death of Rosalyn Albaniel Evara

"Some of her co-workers [on Post-Courier] would take her in after she had been beaten and patch her up – supplying tea and sympathy. Rosalyn begged them not to report her husband’s assaults to the police, as she was afraid for her daughter. And they didn’t. But they all knew. Her beatings were a likely cause of her death – and they all knew..."

As an Australian tax-payer, I object to my hard-earned tax dollars going to a foreign government that tacitly condones the wholesale abuse of half of their population – and then does it with my money.

It is time that international sanctions were applied to Papua New Guinea – time to hit them where it will hurt – in the money pocket. The international community need to express their disgust at the ongoing human rights abuses in PNG – we (the international community) can stop this, even if they won’t.

Let’s make this stop at Rosalyn Albaniel.

Her Story

She died suddenly. People were shocked.

“But I only just saw her yesterday,” and “I was to meet with her Monday,” they wrote incredulously.

For all intents and purposes, for the Senior Business Journalist with one of Papua New Guinea’s leading newspapers, Post Courier, it was ‘business as usual…until she died, that is.

There were outpourings of grief on social media and no doubt many more in the physical world. If there’s one thing that Papua New Guineans do well it is expressing their grief.

“Nooooo – it cannot be true,”

“Why did you leave us so soon?”

they write on social media in the case of loss. And at funerals, even men are heard (expected, even) to wail and cry out “Why, Lord?”

But the shocking truth is, that they had no need to ask “why,” they knew the answer – but they weren’t telling.

Rosalyn Albaniel Evara had been suffering ongoing physical abuse. Her husband often beat her senseless.

The injuries that she sustained are the probable cause of a suspected brain haemorrhage that killed her.

THEY KNEW

It is time that international sanctions were applied to Papua New Guinea – time to hit them where it will hurt – in the money pocket. The international community need to express their disgust at the ongoing human rights abuses in PNG – we (the international community) can stop this, even if they won’t.

Let’s make this stop at Rosalyn Albaniel.

Her Story

She died suddenly. People were shocked.

“But I only just saw her yesterday,” and “I was to meet with her Monday,” they wrote incredulously.

For all intents and purposes, for the Senior Business Journalist with one of Papua New Guinea’s leading newspapers, Post Courier, it was ‘business as usual…until she died, that is.

There were outpourings of grief on social media and no doubt many more in the physical world. If there’s one thing that Papua New Guineans do well it is expressing their grief.

“Nooooo – it cannot be true,”

“Why did you leave us so soon?”

they write on social media in the case of loss. And at funerals, even men are heard (expected, even) to wail and cry out “Why, Lord?”

But the shocking truth is, that they had no need to ask “why,” they knew the answer – but they weren’t telling.

Rosalyn Albaniel Evara had been suffering ongoing physical abuse. Her husband often beat her senseless.

The injuries that she sustained are the probable cause of a suspected brain haemorrhage that killed her.

THEY KNEW

The ongoing beatings would take place within the gated accommodation compound of the employees of Post Courier.

I once went to this complex in Port Moresby to drop off a colleague (a Post Courier journalist), who lived there. Whilst I never went inside the building, my impressions of the complex were that it looked like a block of cheap motel units of flimsy construction.

Living cheek by jowl with your co-workers in this way would not offer much in the way of privacy – and it didn’t. All witnessed the beatings that Rosalyn endured – if not by sight, certainly they would have heard them.

Some of her co-workers would take her in after she had been beaten and patch her up – supplying tea and sympathy. Rosalyn begged them not to report her husband’s assaults to the police, as she was afraid for her daughter. And they didn’t. But they all knew.

Her beatings were a likely cause of her death – and they all knew.

In the wake of her passing, not one word was reported by the Post Courier about the circumstances surrounding her death – yet they all knew.

They attended her funeral yesterday, they sat there and grieved for her, yet they did not utter a word of what they knew. Amongst the grievers would have been her husband. They sat beside him even though they knew what he’d done.

It took a brave lady, Rosalyn’s aunt, Mary Albaniel, to tell all. She chose to tell it at the funeral. It was a tale of sustained abuse and beatings leading to her niece’s death.

Mary Albaniel also had post mortem pictures she had taken of her niece’s body – and she showed these too. Rosalyn’s body was covered with the evidence of her husband’s abuse.

Yet with her bruised and battered body, Rosalyn turned up for work each day and performed her journalistic duties on behalf of Post Courier, her employer – her clothes hiding most of the evidence of her abuse.

Everyone considered Rosalyn Albaniel a good journalist who never failed in her duties to Post Courier – however, as a media outlet wedded to the idea of ‘the fourth estate’ whereby the media are tasked with a duty to expose wrongdoing, Post Courier surely failed Rosalyn.

Why wasn’t the perpetrator stopped (even if he wasn’t formally charged)?

Tea and sympathy for the victim before she’s sent packing back to her tormentor for more of the same, just doesn’t cut it.

Yet, the fault for her death must surely lie with the person who caused it – and that wasn’t her colleagues at Post Courier. But it could have been her husband.

Post Courier employees and others who knew were merely upholding a sick tradition that has emerged in PNG society whereby violence against women has become normalised and where very few men are ever prosecuted for violence perpetrated on women – especially ones deemed to ‘belong’ to the men through an intimate relationship or those that are said to be witches (yes, you heard right – they still burn witches alive in PNG). However, truth be told, women are fair game for men in most circumstances and age is no barrier.

THE SICK TRADITION

When Rosalyn’s Aunty Mary exposed what Post Courier should have at her niece’s funeral, she was wearing an orange T Shirt that said “No to violence against women.”

It was the T Shirt that we wore when we demonstrated against gender-based violence in Port Moresby on 16 December 2016. It was, we thought, a landmark day.

Together with the Governor of the National Capital District (wherein Port Moresby resides) Powes Parkop, who is arguably the sole champion of the cause in the PNG parliament, we managed to put enough pressure on the PNG government that the National Executive Council (PNGs caucus) passed a strategy for combating violence against women that had been languishing in a government department for over 15 months. The irony of that situation was that the negligent minister overseeing that department was one of only three women in the PNG parliament at the time (there are none in this current line up).

The catalyst for the demonstration was a breathtakingly violent incident in the Highlands of PNG.

There was a report of a young woman suspected of cheating on her husband for which her husband sought revenge. He arrived in her village with up to six of his friends and family and they chopped off both her legs with bush knives (machetes) that men habitually like to carry – a bit like Americans like to carry their guns.

I don’t know whether she survived or whether anything was done to those who committed this act because neither matter a damn in Papua New Guinea. She was a woman, and one suspected of being wanton – she got what she’d deserved. As for the men, well, they had every right, didn’t they? That’s the PNG attitude.

It is what enabled Rosalyn’s colleagues to turn a blind eye to her habitual, and clearly savage beatings – even though they are media and are expressly meant to do the opposite. The sick tradition of condoning or ignoring violence against women prevailed.

Since that fateful day last December, not much has changed. Apparently, implementing government strategies take time – and time is something that the PNG parliament seems to have plenty of. Unfortunately time ran out for Rosalyn.

Rest in peace, my esteemed colleague, this journalist is aware of her obligations.

IN THE FINAL ANALYSIS

The female half of the population of PNG are placed in such low esteem that no one cares when she is brutalized.

It is a national emergency treated by the government as a second or third tier priority, if indeed a priority at all or one which deserves more than lip service. People have given up expecting that anything can or will be any different; that anything will change.

But they are wrong. It must be changed. It’s an abomination that needs resources thrown at it.

Yet the PNG government are blazé because there are no votes in it for them and government in PNG is all about hanging onto power.

Besides, many in parliament would have a problem casting the first stone for the reason that one survey (disputed) found that 70% of PNGeans beat their wives. That would make 78 out of 111 MPs potentially wife beaters themselves.

It is time the PNG government was given an urgent imperative to tackle this problem as their priority. To shake them awake from their smug reverie that it’s not their problem because they are men. Let’s do it.

I once went to this complex in Port Moresby to drop off a colleague (a Post Courier journalist), who lived there. Whilst I never went inside the building, my impressions of the complex were that it looked like a block of cheap motel units of flimsy construction.

Living cheek by jowl with your co-workers in this way would not offer much in the way of privacy – and it didn’t. All witnessed the beatings that Rosalyn endured – if not by sight, certainly they would have heard them.

Some of her co-workers would take her in after she had been beaten and patch her up – supplying tea and sympathy. Rosalyn begged them not to report her husband’s assaults to the police, as she was afraid for her daughter. And they didn’t. But they all knew.

Her beatings were a likely cause of her death – and they all knew.

In the wake of her passing, not one word was reported by the Post Courier about the circumstances surrounding her death – yet they all knew.

They attended her funeral yesterday, they sat there and grieved for her, yet they did not utter a word of what they knew. Amongst the grievers would have been her husband. They sat beside him even though they knew what he’d done.

It took a brave lady, Rosalyn’s aunt, Mary Albaniel, to tell all. She chose to tell it at the funeral. It was a tale of sustained abuse and beatings leading to her niece’s death.

Mary Albaniel also had post mortem pictures she had taken of her niece’s body – and she showed these too. Rosalyn’s body was covered with the evidence of her husband’s abuse.

Yet with her bruised and battered body, Rosalyn turned up for work each day and performed her journalistic duties on behalf of Post Courier, her employer – her clothes hiding most of the evidence of her abuse.

Everyone considered Rosalyn Albaniel a good journalist who never failed in her duties to Post Courier – however, as a media outlet wedded to the idea of ‘the fourth estate’ whereby the media are tasked with a duty to expose wrongdoing, Post Courier surely failed Rosalyn.

Why wasn’t the perpetrator stopped (even if he wasn’t formally charged)?

Tea and sympathy for the victim before she’s sent packing back to her tormentor for more of the same, just doesn’t cut it.

Yet, the fault for her death must surely lie with the person who caused it – and that wasn’t her colleagues at Post Courier. But it could have been her husband.

Post Courier employees and others who knew were merely upholding a sick tradition that has emerged in PNG society whereby violence against women has become normalised and where very few men are ever prosecuted for violence perpetrated on women – especially ones deemed to ‘belong’ to the men through an intimate relationship or those that are said to be witches (yes, you heard right – they still burn witches alive in PNG). However, truth be told, women are fair game for men in most circumstances and age is no barrier.

THE SICK TRADITION

When Rosalyn’s Aunty Mary exposed what Post Courier should have at her niece’s funeral, she was wearing an orange T Shirt that said “No to violence against women.”

It was the T Shirt that we wore when we demonstrated against gender-based violence in Port Moresby on 16 December 2016. It was, we thought, a landmark day.

Together with the Governor of the National Capital District (wherein Port Moresby resides) Powes Parkop, who is arguably the sole champion of the cause in the PNG parliament, we managed to put enough pressure on the PNG government that the National Executive Council (PNGs caucus) passed a strategy for combating violence against women that had been languishing in a government department for over 15 months. The irony of that situation was that the negligent minister overseeing that department was one of only three women in the PNG parliament at the time (there are none in this current line up).

The catalyst for the demonstration was a breathtakingly violent incident in the Highlands of PNG.

There was a report of a young woman suspected of cheating on her husband for which her husband sought revenge. He arrived in her village with up to six of his friends and family and they chopped off both her legs with bush knives (machetes) that men habitually like to carry – a bit like Americans like to carry their guns.

I don’t know whether she survived or whether anything was done to those who committed this act because neither matter a damn in Papua New Guinea. She was a woman, and one suspected of being wanton – she got what she’d deserved. As for the men, well, they had every right, didn’t they? That’s the PNG attitude.

It is what enabled Rosalyn’s colleagues to turn a blind eye to her habitual, and clearly savage beatings – even though they are media and are expressly meant to do the opposite. The sick tradition of condoning or ignoring violence against women prevailed.

Since that fateful day last December, not much has changed. Apparently, implementing government strategies take time – and time is something that the PNG parliament seems to have plenty of. Unfortunately time ran out for Rosalyn.

Rest in peace, my esteemed colleague, this journalist is aware of her obligations.

IN THE FINAL ANALYSIS

The female half of the population of PNG are placed in such low esteem that no one cares when she is brutalized.

It is a national emergency treated by the government as a second or third tier priority, if indeed a priority at all or one which deserves more than lip service. People have given up expecting that anything can or will be any different; that anything will change.

But they are wrong. It must be changed. It’s an abomination that needs resources thrown at it.

Yet the PNG government are blazé because there are no votes in it for them and government in PNG is all about hanging onto power.

Besides, many in parliament would have a problem casting the first stone for the reason that one survey (disputed) found that 70% of PNGeans beat their wives. That would make 78 out of 111 MPs potentially wife beaters themselves.

It is time the PNG government was given an urgent imperative to tackle this problem as their priority. To shake them awake from their smug reverie that it’s not their problem because they are men. Let’s do it.