“Creating and maintaining the quality of written expression in the English language in Fiji is very important.”

This is the comment made by Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama during the Fiji National University’s Inaugural Alumni Awards. Bainimarama says far too many people in our schools, tertiary institutions, government, private sector make basic spelling, grammar errors and sentence construction. He says it is a particular curse in the civil service where he continually sees even the most senior people unable to write English with clarity, simplicity and in the correct manner.

Bainimarama adds that instead of choosing simple words to get their message across, they use big words as if they have to demonstrate to everyone that they have been educated. He says some of these people have high degrees from overseas universities but either they haven’t learnt or have forgotten that words are the tools they use to convey ideas." Fijivillage News

Fijileaks: "SET"

The Rise of Singlish in Singapore:

Someone who can only speak English, and not Singlish, may be seen as a bit posh, or worse - not a real Singaporean; Repeated Speak Good English campaigns, drummed into Singaporeans in schools and in the media, have had only limited success. Singlish has not only shrugged off these attacks, it has thrived; Over time, Speak Good English campaigns have evolved from trying to stamp out Singlish, to accepting that properly spoken English and Singlish can peacefully co-exist. The language has even come to be seen as part of Singaporean identity and heritage

Singapore is known for its efficiency and Singlish is no different - it's colourful and snappy.

You don't have a coffee - you "lim kopi". And if someone asks you to join them for a meal but you've already had dinner, you simply say: "Eat already."

Singlish first emerged when Singapore gained independence 50 years ago, and decided that English should be the common language for all its different races.

That was the plan. It worked out slightly differently though, as the various ethnic groups began infusing English with other words and grammar. English became the official language, but Singlish became the language of the street.

Repeated Speak Good English campaigns, drummed into Singaporeans in schools and in the media, have had only limited success. Singlish has not only shrugged off these attacks, it has thrived.

It's been documented in a dictionary and studied by linguists. And it has been immortalised in popular culture. Take for example the 1991 comedy rap song Why U So Like Dat? by musician Siva Choy, which dramatises an argument between two schoolchildren.

"I always give you chocolate, I give you my Tic Tac, but now you got a Kit Kat, you never give me back!" sings Choy.

"Oh why you so like dat ah? Eh why you so like dat?"

Over time, Speak Good English campaigns have evolved from trying to stamp out Singlish, to accepting that properly spoken English and Singlish can peacefully co-exist. The language has even come to be seen as part of Singaporean identity and heritage - it appears in advertising campaigns for SG50, the big celebration of Singapore's Jubilee Year, and will feature on floats in Sunday's National Day Parade.

Among ordinary Singaporeans, Singlish tends to be spoken in informal situations - with friends and family, taking a taxi or buying groceries. It indicates casual intimacy. English, on the other hand, is used for formal situations - at school, or at work, especially when meeting strangers or clients.

Over time, it has become a social marker - someone who can effectively switch between the two languages is perceived to be more educated and of a higher social status than someone who can only speak Singlish.

Someone who can only speak English, and not Singlish, meanwhile, may be seen as a bit posh, or worse - not a real Singaporean.

So how do you speak it?

The grammar mirrors some other regional languages including Malay, which is indigenous to Singapore, by doing away with most prepositions, verb conjugations, and plural words, while its vocabulary reflects the broad range of the country's immigrant roots. It borrows from Malay, Hokkien, Cantonese, Mandarin and other Chinese languages, as well as Tamil from southern India.

Having coffee, "lim kopi", is a combination of the Hokkien word for drink, "lim", and the Malay word for coffee, "kopi".

A person who worries a lot is a kancheong spider - "kancheong" is from the Cantonese word for anxious, and the term evokes the image of a panicked spider scurrying around.

If a situation is intolerable, you may exclaim, "Buay tahan!" The word "buay" is Hokkien for cannot, and "tahan" is Malay for tolerate.

But Singaporeans have also appropriated English words and turned them into something else.

To reverse is to "gostan", from the nautical term "go astern" - a reminder that Singapore was once a British port.

"Whack" means to attack someone, and transposing that to Singapore's favourite pastime, eating, it can also mean ravenously attacking or digging into a hearty meal.

Singlish also has an array of words that are simply invented, that don't mean anything on their own, but dramatically alter the tone of what you're saying when tacked on to the end of a sentence.

"I got the cat lah," is an assurance that you have the cat. "I got the cat meh?" is the puzzled realisation that you may have lost it.

Some Singlish phrases are also used in Malaysia but others are unique to Singapore.

To "merlion" is to vomit profusely, and refers to Singapore's national icon, the Merlion, a half-fish half-lion statue that continuously spouts water.

Thanks partly to social media, Singlish, which used to be only a spoken language, is now starting to evolve in written form with spelling that reflects how the words are pronounced.

"Like that" can be "liddat."

"Don't play play" - a phrase popularised by 1990s sitcom character Phua Chu Kang, meaning roughly "don't mess around with me" - is more accurately written as "Donch pray pray".

Confused? Donch get kancheong.

Spend enough time in Singapore and you sure get it lah: BBC News, Singapore, Magazine, 6 August 2015

From Fijileaks Archive:

From Fiji Sun archive:

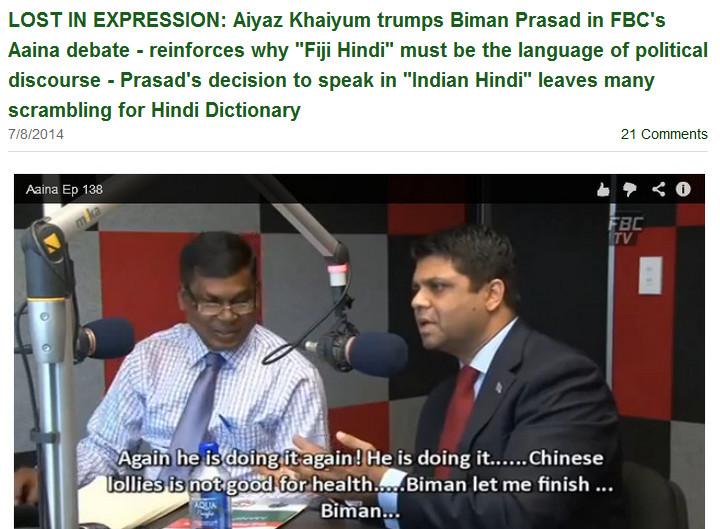

Fiji Hindi baat bolo, Indo-Fijian politicians!

You are not contesting election to Indian Parliament

By VICTOR LAL

ONE of the most ridiculous and nauseating features of the election campaign is the language usage of Indo-Fijian candidates on the election trail: a pseudo pompous and counterfeit Hindi, as if they are contesting for power in India and not in Fiji.

Several potential voters wrote to me complaining that instead of speaking in the everyday Fiji Hindi to them, the candidates have been making speeches in Shudh (Standard/Correct) Hindi, a language a vast majority of the Indo-Fijian voters hardly understand.

A similar spectacle has been displayed during Question Time and Talk Back programmes on Fiji TV. I decided to watch the appearance of Lekh Ram Vayeshnoi of the Fiji Labour Party, Bimal Prasad of the National Federation Party, Shiu Ram of COIN Party and Dildar Shah of the National Alliance Party on these two programmes.

Again, a pathetic reoccurring pattern, as if Vayeshnoi, who is contesting the Nadroga Indian Communal seat, was reading a script out of the Hindu holy book, the Bhagavad Gita. When, all he was trying to do, was to explain his party’s manifesto (for which there is no Fiji Hindi word).

The other three were equally guilty, and at times I felt sorry for Shiu Ram, who even resorted to English to make his point, instead of opting to speak the language of the Indo-Fijian masses, and over 30 per cent of taukei Fijians – Fiji Hindi.

What is wrong with speaking Fiji Hindi? Are they ashamed of the language of their coolie forefathers? Why are these Indo-Fijian candidates contesting the Indian communal seats when they are by commission or omission, speaking to the voters in the language of ‘Mother India’.

For God’s sake, even Indian candidates, despite belonging to different political parties, speak in the 700 different dialects and languages to their prospective voters in India. A regional aspiring candidate in Madras will be speaking in Madrassi, and even the Communist candidate in Bengal will be pouting his Maoist and Stalinist propaganda in Bengali. The Italian-born Mrs Sonia Gandhi, the leader of the Congress Party, also speaks in a Hindi language which is understood by the vast majority of the voters.

More importantly, the candidates in Bihar would be speaking in Bhojpuri or Awadhi, from which the corrupt version of Fiji Hindi has originated in our country. So why can not our own aspiring Indo-Fijian politicians speak the language of their people?.

As Nemani Bainivalu, a University of the South Pacific Hindi graduate, and later a cultural assistant with the National Reconciliation Unit, had once pointed out, only 20 percent of Indo-Fijians can read and write their formal language.

Many Indo-Fijians cannot even read their holy books written in the Khadee Bolee dialect, and pass on religious teachings by word. I am not suggesting that Sudh Hindi be replaced in our education system, or that everyone should be writing novels like Dauka Puran by Professor Subramani of the Department of Literature and Language at the USP.

What I am protesting against is the gibberish Shudh Hindi that is being shoved down the throats of Indo-Fijian voters who are struggling to ‘swallow’ the words. The election message and manifestoes of the political parties would be better understood if the Indo-Fijian candidates resorted to the conversational Fiji Hindi at the hustings. It will also help bring the taukei Fijians into the campaign, especially the 30 per cent who speak the language, and many others who have a smattering command of it.

It must be made very clear to Indo-Fijian candidates that despite the teaching of Shudh Hindi and Urdu in schools, Fiji Hindi is an integral part of the identity and culture of the Indo-Fijian population. It is unique to Indo-Fijians in the world. The day Indo-Fijian politicians kill Fiji Hindi, they will be killing a part of their history and heritage in Fiji.

For no matter where one goes in the world, the moment one hears an Indo-Fijian open his mouth, one immediately asks him: ‘What part of Fiji are you from?’ In a similar vein, India Indians are able to separate us from them solely on the basis of our Fiji Hindi.

If the Indo-Fijian politicians and aspiring candidates are too ashamed to speak to us in the language of our coolie forefathers, they should pack their bags and their manifestoes and take the next Air India flight to India, and wait there for the next general election in that country to practice their Shudh Hindi. We don’t need Indian political impostors in Fiji.

Such candidates and Indo-Fijian leaders do not deserve our sympathy or votes.

Long live FIJI HINDI.