[Response to Fiji Sun comment]

By Jioji Kotobalavu

Under the heading “Facts about i-Taukei land ownership” Fiji Sun editorial writer Jyoti Pratibha stated [F/S July 15] that “there is no threat or danger against [indigenous customary-owned] land”.

According to her, this is in light of the assurance given in the 2013 Constitution under Article 28 that i-Taukei, Rotuman and Banaban customary-owned land shall remain with them and cannot be permanently alienated.

It is surprising that the Fiji Sun has come to this very simplistic and subjective conclusion without considering other relevant facts in order to establish what the truth really is about the protection of indigenous communal land rights under the Bainimarama/Saiyad-Khaiyum 2013 Constitution and their Land Use Decree 2010.

Had they conducted more research on the matter, they would have found that the objective truth is quite different.

So what is the objective truth about the purported assurance under Article 28?

Any intelligent and politically unbiased objective observer knows that to determine whether in reality this Article 28 purported assurance can be trusted as being reliable and dependable, it must be looked at from the perspective specifically of the indigenous landowners. And here, the real test of the efficacy of this assurance is whether the indigenous landowners can freely exercise the associated and secondary rights that derive from their customary ownership of their communal land. The most important of these is their right under the common law to seek the protection of the courts in circumstances where they consider and can adduce evidence to support their application that the public authorities concerned, be it the NLTB under the Native Land Trust Act, or the Prime Minister under the Land Use Decree 2010, have not properly discharged their statutory and fiduciary duty to ensure that the best interests of the landowners are securely safeguarded in the land lease, or logging concession, or mineral/underground water extraction licence which these public authorities have granted on their land.

In the precedent-setting case of Narawa and Matanabua v NLTB (2004) it was established by the Supreme Court that a landowning Mataqali as an unincorporated collective proprietary entity has the legal standing under the common law to apply to the courts for a judicial determination and redress of grievances they may have vis-à-vis the NLTB about contractual dealings by the NLTB over its customary-owned land.

Today, when a lease, concession or licence is granted by the Native Land Trust Board under the Native Land Trust Act, a landowning Mataqali may still freely exercise this common law right to seek the protection of the courts if it is considers that the NLTB is not properly discharging its statutory and fiduciary duty to look after their best interests.

But what about the Land Use Decree 2010? Can a landowning Mataqali exercise the same common law rights under this Decree to obtain judicial protection for their landownership rights?

The Decree expressly states under section 6 (2) that the power of the Prime Minister under section 10 to grant leases of up to 99 years is discretionary, and in exercising this power he is required under section 11 to “take into consideration at all times the best interest of the land owners and the overall wellbeing of the economy.”

This power of a public authority is administrative and the courts have interpreted its discretionary character to imply a common law duty by the authority concerned to consult those whose rights or legitimate interests may be directly affected by the specific issue or question under consideration, and for their views to be taken fairly into consideration, before the authority makes a final decision. The objective of this administrative law provision is to ensure that no person is denied procedural justice and fair treatment by those who exercise public power.

These expressed and implied meanings of the provisions of the Land Use Decree confer on the indigenous landowners two possible bases upon which they can bring proceedings in court against the Prime Minister.

Firstly, the landowning Mataqalis in a land lease granted by the Prime Minister under the Decree may apply for a judicial review of the Prime Minister’s decision if all the members have not been consulted and they are not happy with the terms of the lease granted. The application is for the court, on the evidence presented, to quash the Prime Minister’s decision on the grounds either of illegality, or acting unreasonably and irrationally, or for denial of natural justice to the Mataqalis concerned.

The inference here is that it may not be enough to satisfy the requirement for procedural justice for the Prime to act solely on the consent of 60 percent of the Mataqali members in the transfer of their land to the Government’s Land Bank to be dealt with by the Prime Minister under the Land Use Decree. In fact, depending on the consent of only 60 per cent of the Mataqali members is contrary to the traditional way of indigenous Fijian decision-making by collective consensus. If the Prime Minister, for example, is contemplating granting a 99-year lease it would actually be prudent for him, in the interest of procedural justice and fairness to the landowners, to first consult and obtain the consent of all the Mataqali members by collective consensus. It would be very important to do this not only because it is the right of the landowners under the common law to be consulted, but also because it would be in their best interests to give them the opportunity to fully comprehend the consequence of this long term lease to the land maintenance needs of their Mataqali members, now and in the future. Under the NLTB, the land maintenance need of the Mataqali is always considered as the paramount consideration.

In the Narawa and Matanabua v NLTB (2004) case cited above, the Supreme Court had emphasized the point that for a Mataqali to have legal standing before the court the members must give their collective and unanimous consent to the common cause to be pursued and who is to represent them in this.

Secondly, in the event a lease has been granted with the consent of the landowners but that in the course of the lease implementation, the leaseholder, for example, has consistently and unreasonably failed to pay the required rent, or has breached the lease conditions by building permanent structures on the Mataqali land without the requisite prior approval of the landowners, and the Lands Department has done little to rectify the problem, the landowning Mataqalis may sue the Prime Minister with a claim for damages, alleging breach by him of his statutory and fiduciary duty to safeguard the best interests of the landowners.

So in the context of the purported assurance under Articles 28 of the 2013 Constitution, the question that the indigenous landowners are entitled to ask is whether this assurance is really of practical utilitarian value to them when at the same time Bainimarama and Saiyad-Khaiyum, as the promulgators of the Constitution and the Decree, have also effectively denied the landowners their common law right to seek the protection of the courts for their customary proprietary rights.

Consider the following:

[1] Section 15 of the Land Use Decree clearly stipulates that no court, tribunal or commission shall have any jurisdiction to accept, hear and determine any challenge or claim against a decision of any Minister or state official under this Decree. This totally denies the indigenous landowners the right of access to a court in order to seek judicial protection for their rights derived from their common and collective customary ownership of their land. It means that the Mataqali members cannot exercise their common law rights under the Decree, which they can freely do under the Native Land Trust Act and Native Lands Act.

[2] Article 16 of the 2013 Constitution gives every person in Fiji the right to apply to the courts for a judicial review of decisions by those in public authority if these decisions allegedly violate or adversely affect their rights under the Bill of Rights. This right however does not come into effect until after the first sitting of the first Parliament elected under this Constitution. It effectively means that no one has the right to apply for judicial review of any action or decision by the Prime Minister or any other public office holder in the government or a state agency until after the general elections in September. But for indigenous landowners this right of access to the courts for judicial review is totally and permanently denied to them by the operation of section 15 of the Land Use Decree. Where then is the right to equal citizenry which we are told is the foundation upon which the 2013 Constitution is built? Why are indigenous landowners being relegated to lesser rights than owners of freehold land in seeking judicial protection of their proprietary rights? Where is the right to equal access to the courts, or to the equal protection of the law? In short, why are indigenous landowners being differentiated from other citizens and discriminated against in the exercise by them of their common law rights derived from their proprietary rights by custom to their communal land?

[3] And even if indigenous landowners were allowed equal access to the courts for judicial review of, or substantive appeal against, a decision or action by the current government in relation to their customary land, Chapter 10 of the 2013 Constitution would render them futile and ineffectual because it irrevocably grants absolute and unconditional immunity to Bainimarama, Saiyad-Khaiyum and others in the current government from criminal prosecution and civil liability from all their decisions and actions.

So when you consider together the operational effects and consequences of the restriction on the jurisdiction of the courts under section 15 of the Land Use Decree, the blanket immunity from civil liability under Chapter 10 of the 2013 Constitution, and the time limitation on the coming into effect of the right to apply for judicial review under Article 16 of the Constitution, it is unequivocally clear that the Article 28 assurance on indigenous landownership cannot be regarded as being reliable and trustworthy. It can only be so if section 15 of the Land Use Decree is revoked and if the immunity provision of the 2013 Constitution is removed. But it is doubtful whether Bainimarama and Saiyad-Khaiyum will ever agree to this because they are dependent on these provisions for their self-protection.

Undoubtedly, the best protection for the landowners is to return the administration of all dealings on their land to the Native Land Trust Board under the Native Land Trust Act. In addition, the 2013 Constitution must be amended to incorporate into it Articles 185 and 186 in the 1997 Constitution. These two 1997 Constitution provisions entrench all legislation pertaining to indigenous group rights and provide specific mandate to Parliament to enact laws for the application of customary laws and processes.

Fijileaks Editor: Kotobalavu sent his response a while ago but the pro-regime propagandist Fiji Sun is yet to publish it.

From Fijileaks Archive:

By L.Qarase

PROTECTION OF NATIVE LAND

The Attorney –General, Mr. Aiyaz Sayed Khaiyum, has travelled throughout the country telling people that Government’s draft Constitution provides better protection for native land than the 1997 Constitution. This is simply not true and it is a blatant lie. Mr. Khaiyum has told the lie so often that his colleagues in Government, including the Prime Minister, Commodore Voreqe Bainimarama, have come to believe him.

The truth is this: the 1997 Constitution provides for the entrenchment of certain laws covering group rights. These laws include the Fijian Affairs Act, the Native Land Trust Act, the Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Act (ALTA), the Rotuma Land Act etc. Amendments to these Acts would require special majority voting in Parliament, particularly in the Senate. In the Senate, any amendments must be approved by at least 9 out of the 14 members who represent the Great Council of Chiefs. Under this provision it would be difficult to amend any of the entrenched legislation. And if any amendment is passed it would mean that the amendment has the support of the great majority of the people of Fiji.

Under Government’s draft Constitution there is no provision to entrench the rights of indigenous Fijians to their resources and other group rights. In other words the entrenched laws will be like other laws which require simple majority votes in Parliament to effect amendments or even the repeal of laws. Where then is the greater protection claimed by Mr. Khaiyum? There is none! Mr. Khaiyum has argued that this protection is contained in the Bill of Rights. As chief legal adviser to Government the Attorney- General should know better. The Bill of Rights provides for rights of individual citizens, not group rights. Native Land is owned communally, and not by individual indigenous Fijians. His argument, therefore, is false and invalid. Without the entrenchment of laws relating to indigenous Fijian rights it would be fairly simple to take these rights away from them. Indigenous Fijian rights to their land, for example, will be at the whim of the Government in power, since a simple majority in Parliament would be required to effect changes.

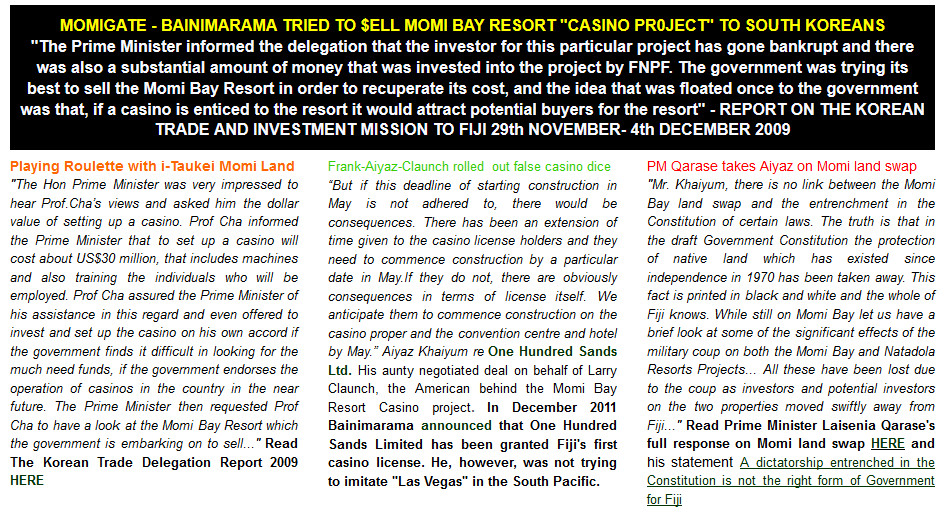

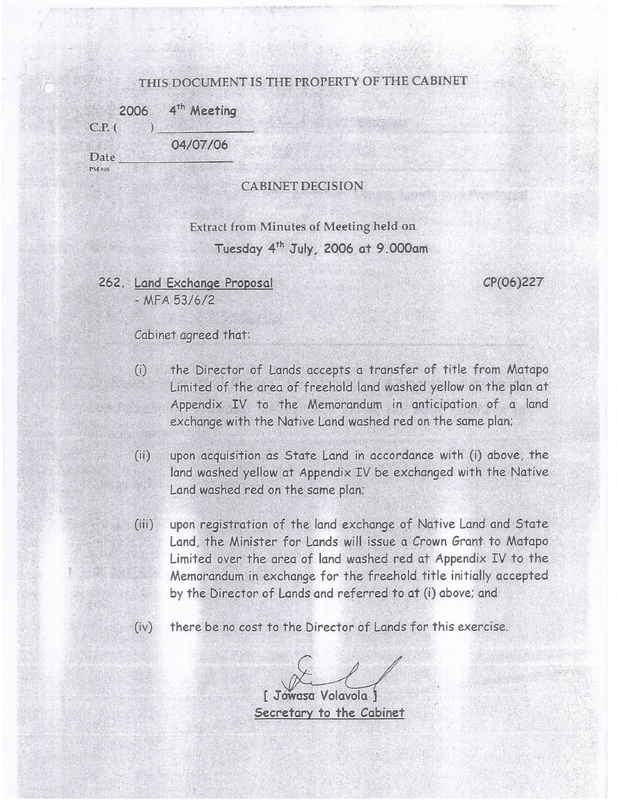

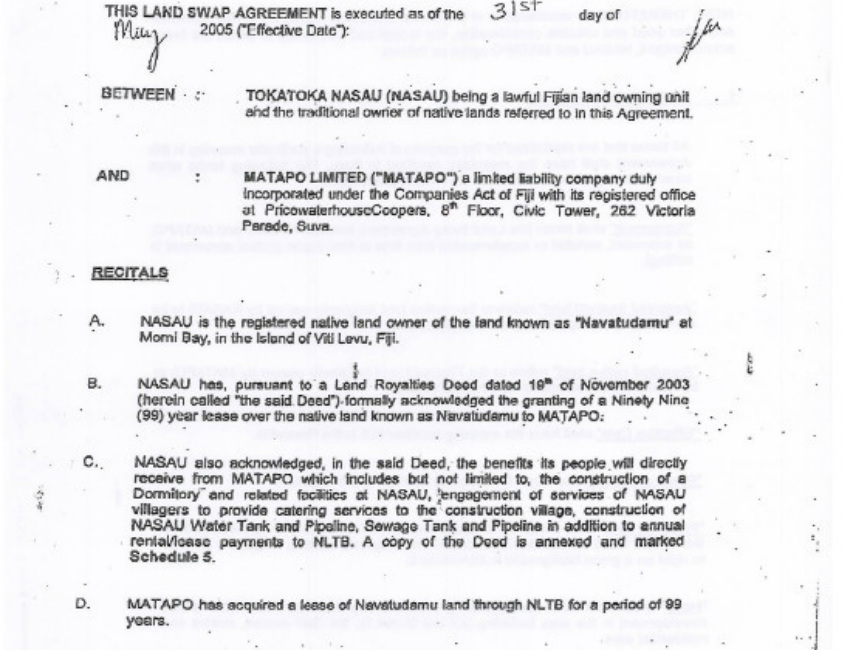

The Attorney General has cunningly diverted attention from the issue of “entrenched legislation” to the land swap or exchange in the Momi Bay Project. The land transaction in question involved the swap or exchange of 68.7 hectares of native land owned by Tokatoka Nasau with freehold land of equivalent area and value owned by Matapo Limited, the developer of Momi Bay Resort Project. Upon exchange the native land was to be converted to freehold and the Matapo freehold was to be converted to native land and registered under Tokatoka Nasau. There was no loss of native land in the transaction because of the equivalent freehold land in exchange. The land swap was made with the voluntary agreement of the two parties involved, Matapo Limited and Tokatoka Nasau. The NLTB gave its consent to the transaction and the Government of the day sanctioned

the land swap under the Land Transfer Act. The terms and conditions of the land swap are recorded in an Agreement between the two parties dated 31st May, 2005. The landowners were obviously satisfied and happy with the benefits they were going to receive which include the following:

· An equivalent land area was exchanged for native land, hence

there was no loss of land;

· The landowners were paid a premium for the transaction;

· The landowners were to become shareholders in the operating

company of the golf course;

· Higher rental income to landowners;

· Jobs priority for landowners and so on.

In addition the agreement reached between Matapo Limited and Tokatoka Nasau was going to make a huge contribution to the overall success of the Momi Bay Resort Project. Mr. Khaiyum, there is no link between the Momi Bay land swap and the entrenchment in the Constitution of certain laws. The truth is that in the draft Government Constitution the protection of native land which has existed since independence in 1970 has been taken away. This fact is printed in black and white and the whole of Fiji knows. While still on Momi Bay let us have a brief look at some of the significant effects of the military coup on both the Momi Bay and Natadola Resorts Projects. Developments on both properties were proceeding well. Projections were that by 2010 – 2012 three to four 5 – star hotels would be operating at Natadola and two or three 5 – 6 star hotels plus a Marina at Momi Bay. About 10,000 direct and indirect jobs would have been created; tens of millions of dollars were to flow into Government revenue annually by way of VAT, PAYE and corporate taxes. All these have been lost due to the coup as investors and potential investors on the two properties moved swiftly away from Fiji.

The absence of adequate protection of native land in the proposed Constitution is a major flaw. There are many other significant provisions which are repugnant and unacceptable in a modern democratic society. The bottom line is that the proposed Constitution will entrench the current dictatorship and for this reason alone it should be totally rejected by the people of Fiji.