"This October 10th Fiji Day celebration is significant in that we have just 4 days earlier witnessed our first Parliamentary sitting in almost 8 years. This occasion will no doubt give all of our people hope that the future of our Nation and the well-being of our people looks positive. As Leader of the Opposition I can say we that we stand ready to play our part in building a positive way forward for our people and as long as there is the will among the 50 newly elected Members of Parliament to turn the often misused words of Accountability, Transparency and Inclusiveness, into real measurable deeds that the people can see happening, then there is good reason to be optimistic in our future.

As I reflect back on the significance of this day I cannot help but be saddened by the fact that the actions of my ancestors who ceded these islands to Queen Victoria in 1874 and the return of the Islands to the Chiefs and people of Fiji by HRH Prince Charles on behalf of Queen Elizabeth II on our Independence day in1970 is not recorded for its historical significance in the constitution of Fiji.

Yet we celebrate it with all the pomp and ceremony befitting its significance. On this October 10th Fiji Day celebrations I urge all citizens in Fiji to take a moment to prayer and give thanks for the small blessings that this first step back to democracy has given us and let us hope that the promise given to our people that there will be no more coups becomes a reality.

May God Bless Fiji and all her good people on this our Independence Day."

Authorized

Ro Teimumu Kepa

Leader of the Opposition

By VICTOR LAL

5 OCTOBER 2008

The Deed of Cession: A Historical Snapshot

A Fijian language explanation of the Deed of Cession of 1874, recently found in Levuka, has once again excited our interest and imagination in the historical document, especially at a time when the traditional authority of the chiefs, their traditional institutions, and their land rights, are being trampled upon through the agency of a military coup, and supported by a few pro-coup taukei chiefs, and unelected politicians.

How did the chiefs come to cede the country to Great Britain on 10 October 1874? Which chiefs affixed their signatures to the historical deed? What was ceded to Queen Victoria of England and the Empress of India? It should be pointed out that the offer of cession was made as far back as 1859 but I will confine myself to the last few months leading up to the cession. I have decided to retain the original names of all those involved in the cession as it appeared in the documents and also of the places, to give the narrative a sense of history and immediacy.

On 15 July 1874, the Earl of Carnarvon (Lord Carnarvon), the British minister responsible for the colonies, informed Sir Hercules Robinson, the governor of New South Wales in Australia, that the British government had determined that it was necessary to decline the acceptance of the cession of Fiji on the conditions appended, with the signature of Mr Thurston, to the Commissioner’s Report, but would recommend Queen Victoria to accept it on the general understanding, namely, that the chiefs, withdrawing all conditions, would trust to the generosity and justice of Her Majesty - the Queen of England. Sir Hercules was invested with authority to act alone on the question of annexation. In telegrams dated the 15th, 16th, and 17th August, Sir Hercules replied to Lord Carnarvon and asked, first, whether, in the event of an unconditional cession being made, he had the authority to act as he did in the case of Kowlun, near Hong Kong, i.e., to accept the cession in the Queen’s name, and make the best available temporary arrangements for the establishment of a provisional government, pending the issue of an Order in Council prescribing a form of constitution and providing for legislation

He next inquired what was to follow in the event of the chiefs declining to make an unconditional offer, as the existing temporary arrangement under which order was maintained by the Consuls supported by men of war could not continue. On 25 August, Lord Carnarvon telegraphed to Sir Hercules that he was at liberty to accent the cession of Fiji if it should be unconditional or virtually unconditional, and to make arrangements for a temporary government. Sir Hercules telegraphed on 6 September that he now only awaited Mr Parkes, the NSW Premier’s return to Sydney, and expected to start for Fiji in the Pearl on Saturday 12 September, which he did, and after a passage of eleven days, including a stopover of 24 hours at Norfolk Island, he arrived in Levuka harbour on the afternoon of 23 September.

Sir Hercules at once learnt that the general feeling amongst the white settlers, and also amongst some of the natives, in favour of annexation, was less strong than it had been in consequence of the recent debate in the British House of Lords upon Fiji, a report of which had been received at Levuka before his arrival. Persons whose interests were adverse, Sir Hercules told Lord Carnarvon, to the establishment of good government had taken advantage of expressions in Lord Carnarvon’s speech as to the Crown right of pre-emption in all lands, and as regards the “severe” form of government which would have to be adopted in the event of annexation, to excite distrust in the minds of both Europeans and natives on these subjects. The wildest reports, Sir Hercules claimed, were circulated. All private lands were to be confiscated, and Fiji was to be a penal settlement. Already 300 marines had left Portsmouth to garrison the place and coerce the inhabitants! Sir Hercules merely mentioned these absurd rumours as their prevalence obliged him, in his subsequent negotiations, to correct as far as he could such “mischievous misrepresentation”.

Upon the day after his arrival, Sir Hercules paid a formal visit to King Thakombau and four other principal ruling chiefs, who had come to Levuka to meet him. Sir Hercules annexed an extract from the Fiji Times of 26 September 1874 giving an account of this interview, during which no business was transacted; but he informed King Thakombau that whatever he (the King) felt inclined to enter upon business, he (Sir Hercules) would explain to the King frankly and fully the object of his visit. On 25 September, Thakombau went to see Sir Hercules by appointment on board the ship Dido (the Pearl being engaged in coaling) and they then discussed unreservedly the question of annexation in all its bearings. Sir Hercules placed clearly before Thakombau the views of the British government. At first, according to Sir Hercules, Thakombau seemed much depressed and reserved, but before the close of the interview, which lasted for more than two hours, he became cheerful and communicative, illustrating the opinions which he expressed with much force and humour, and in a manner which showed clearly that he perfectly apprehended the points under discussion.

At the commencement of the interview, according to Sir Hercules, Thakombau said he would take time to think of his position, and would consult with other chiefs as to what was best to be done; but towards the close he expressed himself strongly in favour of an unconditional cession of Fiji to Queen Victoria, observing that, “any Fijian Chief who refuses to cede cannot have much wisdom…If matters remain as they are, Fiji will become like a piece of drift-wood on the sea, and be picked up by the first passer by…By annexation the two races, white and black, will be bound together, and it will be impossible to sever them.”

Thakombau ended as follows: “The interlacing has come. Fijians as a nation are of an unstable character, and a white man who wishes to get anything out of a Fijian, if he does not succeed in his object today, will try again tomorrow, until the Fijian is either wearied out or over persuaded, and gives in. But law will bind us together, and the stronger nation will lend stability to the weaker.” The result of the interview was, Sir Hercules concluded, on the whole, entirely satisfactory, and the views expressed by Thakombau displayed “so much intelligence and unselfishness that I am sure your Lordship will feel interested in perusing a full report of the conversation”. On 28 September it was intimated to Sir Hercules a message from Thakombau that, after two days’ discussion in Council, he and the other chiefs then present in Levuka had agreed to the following resolution: “We give Fiji unreservedly to the Queen of Britain, that she may rule us justly and affectionately, and that we may live in peace and prosperity.”

Sir Hercules then forwarded to Thakombau a draft of the Deed of Cession which he (Sir Hercules) had prepared, and stated that, when it had been interpreted and fully explained to the chiefs, Sir Hercules would be prepared to accept the signatures of such of them as were in Levuka, and on its execution by the remainder of the ruling authorities Sir Hercules would formally accept the cession, and establish a provisional government until the Queen’s pleasure as to the future constitution of the islands could be known. The following day, the 29 September, was devoted by the chiefs to the consideration of the Deed of Cession, and in the evening it was intimated to Sir Hercules that Thakombau and chiefs would be prepared to sign at Nasova, the public offices of Levuka, on the morning of the 30 September. Sir Hercules accordingly proceeded to Nasova at 10 o’clock on the morning of the 30th, when Thakombau read and handed to Sir Hercules the formal resolution of the Council giving Fiji “unreservedly to the Queen”. The Deed of Cession was then read in Fijian, and the instrument executed by Thakombau and the four other ruling chiefs who were present.

Sir Hercules then invited Thakombau to accompany him on a tour of the islands to obtain the signature of Maafu and of other chiefs not then in Levuka, whose assent was necessary to the validity of the cession. This Thakombau at once cheerfully agreed to, and they left Levuka the same afternoon in the ships Pearl and Dido for Lomaloma, Maafu’s capital, at which place they arrived on the morning of 1 October.

According to Sir Hercules’ note to Lord Carnarvon: “That day was occupied in receiving and paying visits of ceremony, and on the morning of the 2nd, Thakombau brought Maafu, the Chief of Lau, and Tui Thakau, the Chief of Thakaundrove, on board the Pearl, where the Deed of Cession was fully explained to and executed by them. I am now on my way to Ritova, the Chief of Mathuata in Vanua Levu, and propose, when I have received his assent to the cession, to return to Levuka, where I hope to find assembled the few remaining chiefs whose signatures it is desirable to obtain. Practically, however, with Thakombau’s, Maafu’s, and Tui Thakau’s unconditional tender of cession, the question may be disposed of. When the chiefs have all executed the deed, I shall formally accept the country in the Queen’s name, and assume the administration of Government.”

There was one clause in the Deed of Cession upon which Sir Hercules thought it as well to make a few explanatory observations, and that referred to Clause 4, which dealt with the land in Fiji.

Wise words from Ratu Epeli but… October 9, 2014

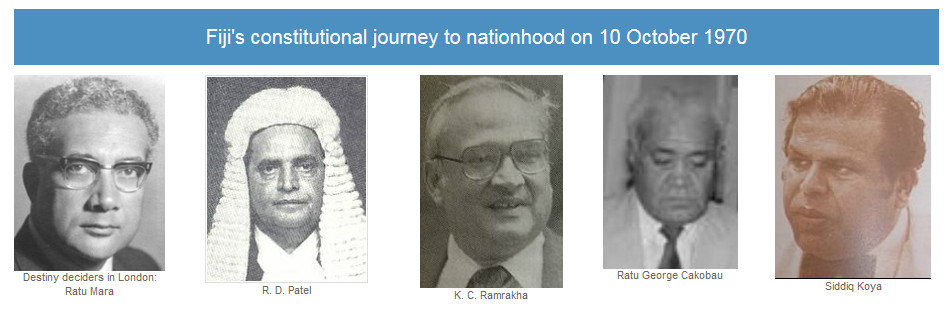

Our President, Ratu Epeli is right when he says Fiji is listening and watching what the Government does. Now they are elected, Bainimarama and Khaiyum have a responsibility to the people they didn’t have when they were self-appointed. What was really interesting, however, was Ratu Epeli’s choice of MPs who embodied all the best from the past. “Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, AD Patel, Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau, Siddiq Koya, Dr Timoci Bavadra, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, Julian Toganivalu, Semesa Sikivou, Douglas Brown, Bill Yee, Loma Livingstone, Adi Losalini Dovi, and Irene Jay Narayan.” Why no Karam Ramrakha? A majority of them are Alliance MPs! And all products of the old colonial days. No-one would ever have heard of Loma Livingstone and Bill Yee if we didn’t have the huge over-representation of European and Chinese voters as hangover from colonial days. And what about Jo Kamikamica or Adi Kuini?

The tenth of October is a memorable date in Fiji’s historical and political calendar. In 1874 it recorded the surrender of the islands’ sovereignty to Great Britain, and in 1970 the end of British rule and Fiji’s entry into the Commonwealth of Nations as an independent state.

In August 1969 a series of discussions took place between the Alliance Party and the National Federation Party to consider further constitutional changes and, on 3 November 1969, the two major parties agreed that Fiji should become independent by way of Dominion status. This sudden, amicable agreement was possible because in October 1969, during the negotiations, the leader of the NFP, A. D. Patel, had died. His successor, Siddiq Koya, a lawyer by profession, proved flexible and conciliatory towards the Alliance Party and its leader Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara; also, the gesture on the part of the Fijians temporarily forced the Indo-Fijians to shelve their demand for common roll.

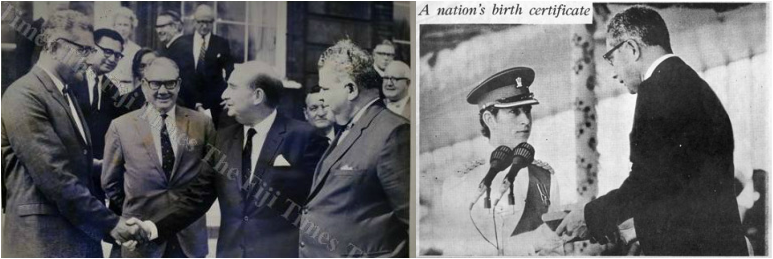

During the series of discussions in August 1969 the Alliance favoured Dominion status, with the Queen as constitutional monarch, represented in Fiji by a Governor-General. The NFP envisaged Fiji as an independent state, with an elected President of Fijian origin as its head, but Fiji should be a member of the Commonwealth. Both parties agreed on Commonwealth membership and that Fiji should proceed to independence. Events abroad had again influenced their decision; this time it was the violence in Mauritius, on 12 March 1968, the day of Independence. Following the broad agreement between the two parties, Lord Shepherd, the British Minister of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, visited Fiji from 26 January to 2 February 1970, “to acquaint himself at first hand with the position reached in the talks”. The parties agreed on most issues except on the composition of the Legislature and method of election. The Constitutional Conference was subsequently held at Marlborough House in London from 20 April to 5 May 1970.

On 30 April, in the course of the Conference, Ratu Mara announced that agreement had been reached on the interim solution. He told the Conference, in plenary session, that he had discussed the matter further with Koya, the Leader of the Opposition, and they had agreed that he should make the following statement to the Conference: “The Alliance Party stated that as in 1965 they recognised that election on a common roll basis was a desirable long-term objective but they could not agree to its introduction at the present state. On the other hand the National Federation Party reiterated its stand that common roll could be introduced immediately in Fiji and could form the basis of the next general election without in any way one race dominating others but resulting in a justly representative national Parliament.'

The two parties having regard to the national good and for peace, order and good government of independent Fiji reached the following conclusions...that the democratic processes of Fiji should be through political parties, each with its own political philosophy and programme for the economic and social advancement of the people of Fiji cutting across race, colour and creed, and that all should work to this end. The Conference called upon the Government of Fiji to see the immediate completion of the extension of common roll to all towns and township elections, in particular, Lautoka and Suva. The Conference also agreed that at some time after the next election and before the second election the Prime Minister, after consultation with the Leader of the Opposition, should arrange that a Royal Commission should be set up to study and make recommendations for the most appropriate method of election and representation for Fiji and that the terms of reference should be agreed by the Prime Minister with the Leader of the Opposition.

The Conference further agreed that the Lower House should be composed as follows: Fijian (Communal, 12, National Roll, 10); Indo-Fijian (Communal 12, National, 10), General (Communal, 3, National, 5). In agreeing to this composition for the Lower House the parties acknowledged that this is an interim solution and provides for the first House of Representatives elected after Independence, and the Parliament would, after considering the Royal Commission Report, provide through legislation for the composition and method of election of a new House of Representatives, and that such legislation so passed would be regarded as an entrenched part of the Constitution.”

It was also agreed that a Senate comprising 22 members be appointed by the Governor-General on the basis of nominations distributed as follows: Prime Minister, seven; Leader of the Opposition, six: Great Council of Chiefs, eight; and Council of Rotuma, one. Nevertheless, the Senate, which was created at the suggestion of the Indo-Fijian delegates, was designed to serve as protector of the land rights and customs of the native Fijians. Any legislation that affected these rights could be vetoed by the representatives of the Great Council of Chiefs. It may be noted that, while the Indo-Fijian leaders opted for a small piece of the political pie rather than none, the 1970 Marlborough House Conference was a solid victory for native Fijians. The Fijians were a minority and the Constitution went out of its way to safeguard their interests.

That the British had devolved upon the two major communities the responsibility of reaching an agreement provoked severe criticism, and the Indo-Fijian leaders did not hesitate to raise the issue. The following exchange between R. D. Patel (who became the first Speaker of the House of Representatives after independence) and Lord Shepherd, exemplifies the situation:

R. D. Patel: Surely, Britain had kept the races apart for the last 90 years, and now it must take some responsibility to bring them together. It cannot just leave us to our own devices.

Lord Shepherd: My dear chap, if I had to assume responsibility for the sins of my British forefathers for the past 300 years, I would hardly be sitting here as a Minister of the Crown. Indeed, I would be in sackcloth and ashes doing penance in some monastery.

In his 1971 New Year message, Ratu Mara, as Prime Minister of independent Fiji, described 1970 as the “year of hope fulfilled”. The peaceful transition from colony to independence for him was “a pearl of great price which can perhaps be shared with the world at large.”

On 10 October 1970 Fiji became independent, ending some of the social and political tensions of over three-quarters of a century of British rule. The country moved into an equable political climate of a parliamentary democracy in which rival communal parties were to compete for power. The political leaders signed the 1970 Constitution, which assumed the operation of representative and responsible government using the Westminster model, but future conflicts were by no means unlikely.

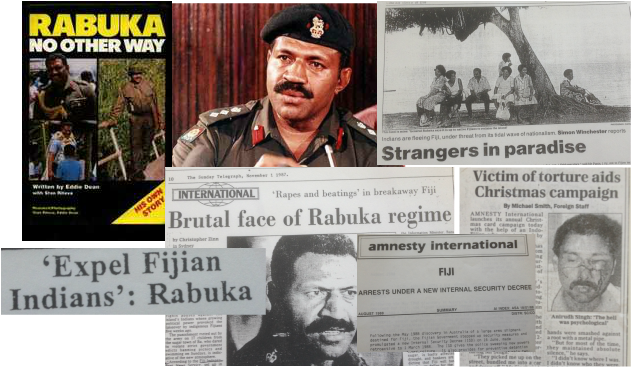

Tragically, Fiji has been turned from paradise to coup coup land.

"Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage" - The Indo-Fijians fought back, from inside and outside Fiji, for their rights as promised to them in the 1970 Constitution of Fiji:

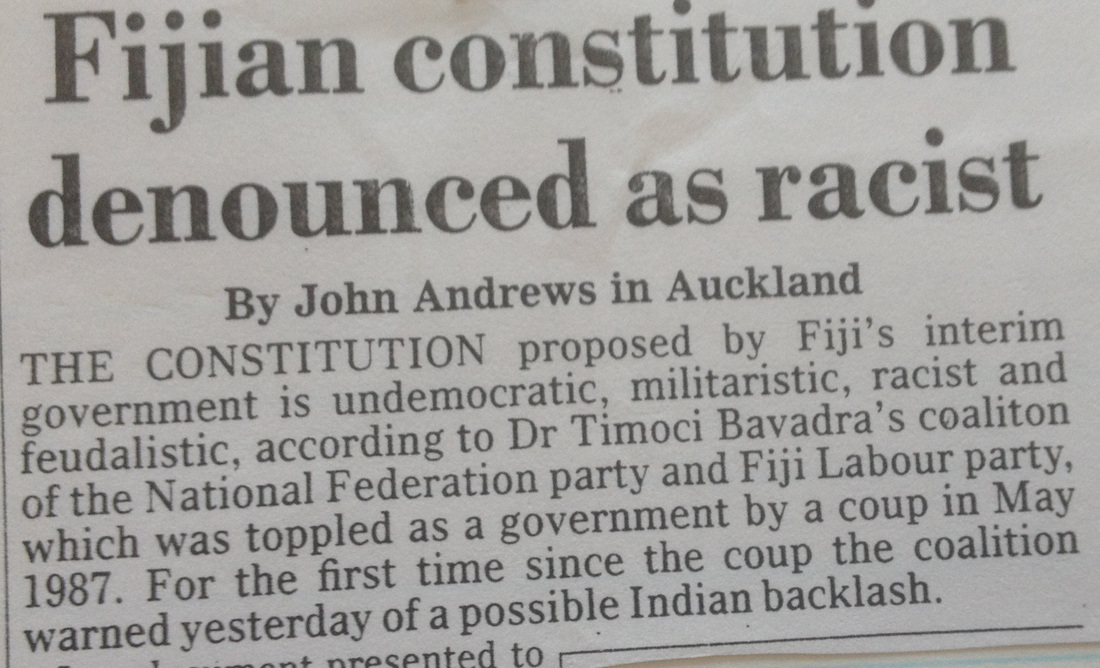

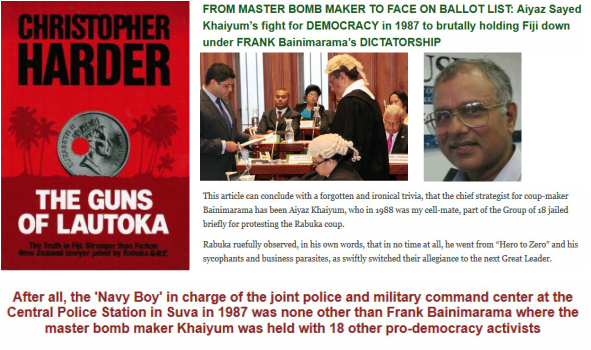

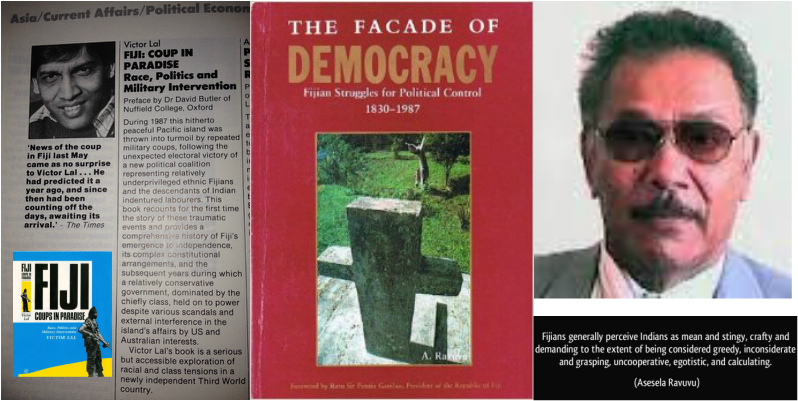

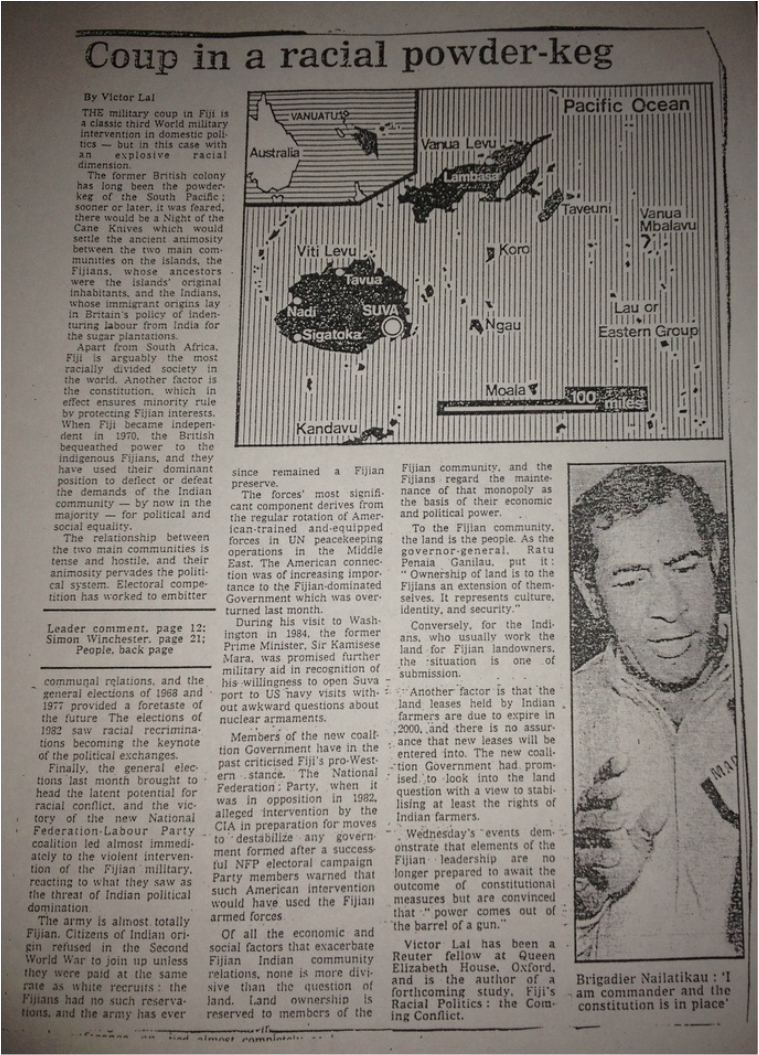

Lest we forget other HISTORY MEN from Rabuka's 1987 Coups:

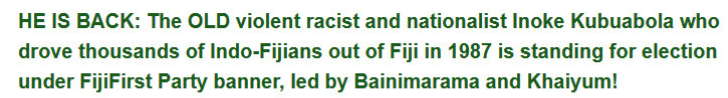

In 2000 George Speight coup, he had re-emerged to take swipe at his opponents who were standing up for Indo-Fijian rights: “Victor Lal’s articles [in Fiji's Daily Post] all have a simple, indeed simplistic stance, restore Chaudhry and impose democracy as defined by Lal and his friends. What he is advocating is an Indian supremacist doctrine, a new version of Hitlerian herrenvolk for Fiji. The racism lies in his desires, not those of us Fijians. His obsession to control Fiji, blinds him to his own ambitions.” 24 August 2000, Kubuabola had attacked Victor Lal after joining post George Speight coup as Minister for Information in the interim and Bainimarama appointed Qarase led government.

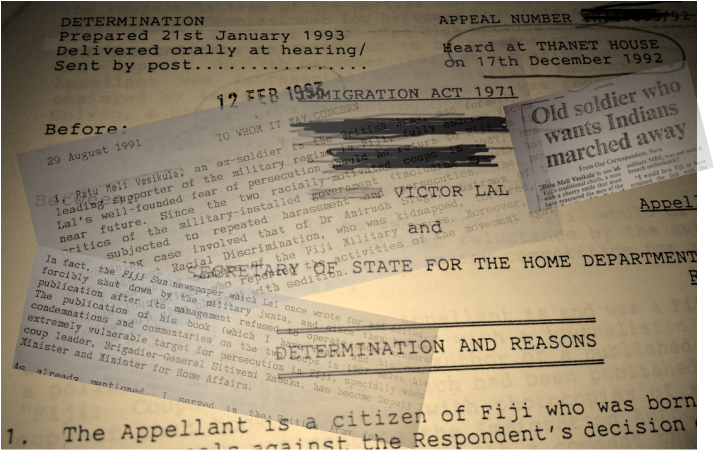

Fijileaks Editor: Kubuabola's outburst was hardly surprising, for he was among a handful who were charged with hunting down the opponents of Rabuka's 1987 coups, as confidential documents and evidence tendered in Victor Lal's asylum trial in London revealed, some from is own former right-hand man and leader of the violent i-Taukei Movement, Ratu Meli Vesikula, later a convert to multi-racialism. We hope to reveal Kubuabola's part one day as we re-write the history of the 1987 coups and the role of the secret Special Operations Security Unit and the list of persons wanted 'dead or alive' - in Fiji and Abroad

Parting of Ways: Lal and Nailatikau found themselves on opposite sides!

London to Government House

London to Government House a day after the racist coup!

In a cruel twist of irony, Victor Lal's journey into exile and the fight for Indo-Fjian rights began in 1987 when the Bavadra government was overthrown in a racially motivated Rabuka coup. Mahendra Chaudhry was Bavadra's Finance Minister. In 2008, Lal fell foul of another military dictator, Frank Bainimarama, when he exposed Chaudhry's $2million from Haryana. Chaudhry was Minister for Finance.

There might be a NEW DAWN for Fiji and for Indo-Fijians but for Victor Lal his BELOVED Fiji is still an OLD DARK country. The ghost of Rabuka still lingers on. But we must remember: 'An Opponent of a Dictator is an Enemy of the State'. Its not what the President of Fiji is saying in 2014, it is what George Orwell wrote in 1984: “One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship.”

A HAPPY BIRTHDAY FIJI!