In fact, both bodies would have had few powers under the FCC’s proposed arrangements other than selecting a largely ceremonial president. Although accompanied by much rhetoric about doing away with ethno-nationalist traditional rulers, Bainimarama’s disbanding of the Great Council of Chiefs was better identified as just one among many post-coup steps to remove or assume control over organs of popular accountability, including also the municipal authorities, the provincial councils and the Sugar Cane Growers’ Council. In any case, both provisions might easily have been amended by the scheduled constituent assembly.

By contrast, New Zealand Foreign Minister Murray McCully reacted in horror at the wastage of his country’s aid money entailed by the ditching of the FCC report (ABC, 11 Jan, 2013). According to one of the Fiji-focussed weblogs, Price Waterhouse Coopers’ audited accounts indicated that, of the F$1.6m used by the FCC, New Zealand had provided F$582,510 (36.4%), Australia had given F$601,772 (37.6%), and the European Union F$248,054 (15.5%), with the remainder coming from the British High Commission (F$108,330) and the American Bar Association (F$59,648) (Coup 4.5, 18 Dec, 2013. F$1 is equivalent to US$0.54). No funding had come from the Fiji government, although Yash Ghai’s team had been allowed to use the otherwise empty parliamentary complex at Veiuto.

There were also other reasons for weak Fiji government commitment to the FCC process. The Ghai draft created the possibility of revival of court proceedings to seek redress for past injustices (FCC 2012, Schedule 6, S. 24), potentially opening the door to action by disgruntled pensioners angered by reforms to the Fiji National Provident Fund. Critically, the ‘Transitional Arrangements’ would have entailed Bainimarama and his cabinet colleagues relinquishing power ahead of the 2014 elections to a ‘caretaker cabinet’ comprising a maximum of 15 ‘former senior public officers’ recommended by a ‘Transitional Advisory Council’ [FCC 2012, Schedule 6, S10 (5), S.17, (3)]. This they were manifestly unwilling to do. Indeed, as the year elapsed, it became ever clearer that the scheduled election was not intended to permit the ouster of the Bainimarama/Sayed-Khaiyum government, but rather to supply this with the oxygen of popular legitimacy.

In a January address to the nation, Bainimarama promised a new draft constitution by the end of the month, and said that the scheduled Constituent Assembly would gather in February, with the constitution to be finalized in April (Bainimarama 2013a). Yet the weeks rolled by, and self-imposed deadlines slipped. In the meantime, the government issued a decree requiring Fiji’s established parties to register within 28 days, party names to be in English, and each to collect 5,000 signatures, 2,000 in the Central Division, 1,750 in the Western Division, 1,000 in the Northern Division and 250 in the Eastern Division (Fiji government 2013a). In a February amendment, trade unionists were disqualified from holding office, parties were forbidden from complying by changing names but retaining the same acronym, and media organizations were threatened with F$50,000 fines or 5-year prison terms for depicting non-registered groups as ‘parties’ (Fiji government 2013b).

The new rules drew protest both from the politicians and overseas lawyers about breaches of human rights and International Labour Organization Convention rules (RNZI 22 Feb 2013). In the Australian Senate, foreign minister Bob Carr rejected suggestions that his government had ‘gone soft’ on Fiji and justified continuing travel bans on military officers and interim government ministers by reference to the draconian party regulations (Carr 2013a). Fiji’s established political organizations eventually complied with the new decrees, but the interim government suggested that they had collected fraudulent signatures.

The new rules most obviously targeted the Qarase’s Soqosoqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua (SDL), which in response initially changed its name to the Social Democratic Liberal party so as to conform with the requirement for an English rather than Fijian name while retaining the publicly well-known acronym SDL (RNZI, 28 Jan). After the second decree forbidding continued use of earlier initials, the party modified its acronym to SODELPA (SOcial DEmocratic Liberal Party), a shift that generated such hilarity as to give the new title rather unexpectedly wide currency.

Only in March did the government release its draft constitution (Fiji Government 2013c), together with a new decree that dropped plans for this to be deliberated upon, and finalized, by a regime-selected Constituent Assembly. This was yet another breach with the regime’s own roadmap as set out in decrees 57 and 58 of 2012 (Fiji Government 2012a, 2012b). The explanation given was that this was ‘forced upon us because of the lack of commitment by the political parties to register under the requirements of the law’. ‘Instead of presenting the draft to the Constituent Assembly under the previous arrangement’, Bainimarama announced to the nation, ‘we will be presenting it directly to you. My fellow Fijians, you will be the new Constituent Assembly’ (Bainimarama 2013b). The real reason for the cancellation was at least in part simply timing, i.e., because of delays occasioned by the rewriting of the constitution, but this was not the first indication of government discomfort with public dialogue, even of a type involving hand-picked supporters. Planned consultations on the FCC report had been cancelled in October 2012. In 2009, dialogue sessions with political parties and plans for a President’s Political Dialogue Forum had been dropped.

On 21 March, a new deadline of 5th April was announced for public submissions. Yet this was only two weeks away. After protests, the deadline was extended. By now, the enthusiasm stimulated by the 2012 constitutional review process had given way to a wave of despondency and disengagement, at least amongst the political elite and civil society groups. In total, the government claimed to receive 1,093 fresh submissions, well below the 7,000 obtained by the FCC over 2012. The new submissions were not publicly released, unlike those received by the FCC. The 2012 submissions had initially all been publicly available on the FCC website, although the links were soon broken, and by the end of the year that website itself had vanished.

The deliberations of Attorney-General and his legal team were mostly behind closed doors. Once the draft was released, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum toured the country explaining and extolling the virtues of its new provisions (see Ministry of Information 2013, Fiji Sun, April 30, 2013). When former education minister and Rewa chief Ro Teimumu Kepa led a delegation to the Attorney-General’s office to present a submission criticizing the draft constitution in April, neither Sayed-Khaiyum nor his Solicitor General made themselves available to receive this (Fiji TV News, 3 April, 2013). A few days later, Bainimarama told villagers in Naitasiri that Fiji’s people weren’t interested in politics, but ‘were more concerned on developments like electricity, water and education’ (Fiji TV News, 6th April, 2013). For the urban and overseas audiences, the government’s Washington-based public relations firm, Qorvis, produced carefully designed propaganda footage about the new draft constitution for public consumption. One of the Qorvis speech-writers privately admitted that those few people presently in command of government knew very well that their position was unsustainable (Hooper 2013: 54).

The Government’s March draft envisaged Bainimarama’s cabinet remaining in office not only after the serving of writs for election, but up to the first sitting of parliament. As with the FCC draft, communal constituencies – in which Fiji’s ethnic communities have since colonial days voted separately for candidates of their own ethnicity – were to be abolished. There was to be a 45-member parliament serving a four-year term, but no upper house. Gone were the FCC’s plans for a National People’s Assembly and for a closed list proportional representation (PR) system together with a New Caledonia-style Law on parity designed to increase women’s representation. Instead, there was to be an open list PR system under which voters choose not only their favoured political party, but also their preferred candidates within political parties. This echoed the recommendations of the 2008 National Council for Building a Better Fiji, and of Catholic priest Father David Arms, a locally resident electoral specialist who soon found himself appointed to the new electoral commission.

The new draft constitution entailed a considerable concentration of power in the hands of the Prime Minister and his Attorney General (see CCF 2013a). The International Senior Lawyers Project (ISLP) concluded that it was ‘not designed to establish a stable constitutional democracy in Fiji’. Insofar as the draft addressed ‘the deep divisions in Fijian society that have contributed to the instability of Fiji for the past century’ it did so by ‘ignoring them – by insisting on ethnically blind constitutional arrangements’ (ISLP 2013: 4). In the FCC draft, the Republic of Fiji Military forces (RFMF) had been primarily responsible for ‘defence and protection of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic’ but able to be deployed domestically only under the control of the police commissioner and with the ‘prior approval of the Minister responsible for defence’ (FCC, 2012, S.176). The new draft reverted to the controversial 1990 constitution’s provision granting the RFMF broad-ranging responsibility ‘to ensure at all times the security, defence and well-being of Fiji and all its residents’ (Fiji Government 2013c. S. 130 (2)). It was to be exceptionally difficult to amend the constitution. After approval by a super-majority in parliament, a constitutional amendment would require a 75 percent majority in a referendum, a threshold far higher than that usually adopted for democratic constitutions. The ‘coup to end all coups’ had found for itself a new legal framework that was only ever likely to be changed by illegal action.

In March, a survey was released by the Pacific Theological College's Institute of Research and Social Analysis. It had entailed discussions with focus groups involving 330 people and in depth interviews with 82 people over 2011-12 (Boege et al 2013). The interlocutors found that ‘the vast majority’ of respondents wanted a reform of the electoral system (p42), thought the military should be reduced in size (pxv), rejected coups as a method of bringing about change and wanted ‘the military to return power to the people as soon as possible’ (pxv). However, there was also ‘virtually unanimous criticism of political parties and politicians’ (p37). A majority indicated distaste for ‘deficiencies of the leaderships of previous democratically elected governments’ and most did ‘not want a return to the pre-2006 state of affairs’ (pxvi). These were the sentiments Bainimarama tapped into in his regular attacks on ‘dirty politicians’ (Australia Network TV, 24 April 2013, FBC 21 Jan 2013).

The Pacific Theological College's survey found a stark division between supporters and opponents of the current government with the former 'slightly outnumbering those expressing criticism', support tending to be stronger in urban and semi-urban areas than in rural areas, and backing for the military particularly strong among younger people (p39). Another 2013 survey, by Minority Rights Group International, found that ‘a clear majority of indigenous Fijians (iTaukei) expressed disquiet about what they perceived as the government’s anti-Fijian policies’, while ‘non iTaukei respondents were predominantly supportive of government policies and generally felt that interethnic relations had improved since 2006’ (Naidu 2013: 31).

By 2013, the media inside Fiji was carrying a little more criticism of government policies and initiatives than during 2009-12, but self-censorship was nevertheless rampant. The threat of punitive actions for overly critical comment was also clear: in August, a local non-government organization, the Citizens’ Constitutional Forum (CCF) was fined F$27,000 and its Chief Executive Officer Akuila Yabaki sentenced to three months in prison (suspended) for publishing excerpts of a 2011 UK Law Society Charity report titled ‘Fiji: the Rule of Law Lost’ (High Court 2013).

The Fiji Sun was particularly sycophantic. When the Prime Minister publicly denounced former civil servants’ protests about provisions in the new constitution draft which allegedly threatened indigenous land rights, the Fiji Sun published his comments under the headline ‘Stop Lies. PM to former civil servants: End playing on old fears’ (Fiji Sun, 30 April, 2013). Appearing on a panel at the University of the South Pacific, former Vice-President Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi contrasted the 2006 coup with previous coups when the military had swiftly handed power back to civilian leaders. Before publishing this, the Fiji Sun contacted Bainimarama in France for a response, and the resultant story figured centrally the Prime Minister’s denunciation of ‘critics’ and ‘past leaders’ under the headline ‘Not Swayed. PM Tells Critics: Change Mindset’ (Fiji Sun, 17 May, 2013).

In August, the government released the finalized constitution, although changes by cabinet were still to be allowed before the end of the year. This new draft showed some signs of responsiveness to domestic criticism, particularly as regards protection of indigenous land rights and the concentration of powers. Outrageous restrictions on the right to life in the March draft [Fiji Government 2013c: S. 8 (2)] had been criticized by the CCF (CCF 2013a: 9) and were deleted from the August version. As in the earlier draft, there was an extensive bill of rights, including significant new socio-economic rights, but governments would still be allowed to override freedoms of expression, association and assembly ‘in the interests of national security, public safety, public order, public morality, public health, or the orderly conduct of elections’ [Fiji Government 2013e. S.17, (3), S. 18, (2) (a); 19 (2), (a)]. Parliament was to be slightly enlarged to 50 MPs, still considerably below the 71 who sat in the pre-coup parliament. An open list PR system was retained, but in place of the four-constituency model there was now to be a single national constituency with a 5% threshold. Unless complicated in other ways, the result was likely to be a huge ballot paper.

That districting change may have been triggered by the difficulty of fitting the smaller Eastern Division in to a four-constituency model without disturbing proportionality between party vote and seat shares, but it also made sense politically from Bainimarama’s standpoint. The smaller constituency model would have played better for the established political parties, who were more likely to draw on localized bases of support. Open list PR systems entail a counting of party votes and a separate tallying of which candidates within each party have the largest number of votes. In a single constituency model, such systems benefit parties that have candidates with nationwide appeal, who can stack up party votes that enable other, lesser-known, candidates to get elected. With a 5% threshold, Fiji’s new electoral system will penalize the smaller parties (and independents), who are likely to require a minimum of around 20,000 votes to get a single candidate elected

Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum compared Fiji’s new electoral model with those of Israel and Holland (FBC, Aug 22, 2013), but this was inaccurate. Israel may have a single nationwide constituency, but it uses a closed list PR system, which is easier to manage in large constituencies. The Netherlands uses a so-called semi-open or flexible list and has 18 multi-member constituencies. Real world examples of open list PR with large or nationwide constituencies are Columbia’s Senate (with a hundred members) and Brazil, which has some districts and state legislatures that use open list PR and are around the size of, or larger than, Fiji’s proposed 50-member parliament. Aside from the complexity of the ballot paper, and the potential for vacancies to generate by-elections that entail costly nationwide general elections, the new electoral arrangements will eliminate the connection between MPs and specific areas within Fiji. The Attorney-General said this would help address the sense of neglect felt by people in remote parts of the country, although most would conclude the exact reverse. Large constituencies are sometimes chosen to create a close proportionality between party seat and vote shares, but some electoral specialists argue that smaller multi-member districts are able to achieve reasonable proportionality while retaining close ties between MPs and their constituents (Carey & Hix 2011).

Bainimarama’s 2012 ‘non-negotiable’ provisions for inclusion in the new constitution had included ‘the elimination of ethnic voting’, triggering a protracted but confused debate (On which, see also Fraenkel 2009). Ending use of ethnically reserved seats could not, in itself, halt voting along racial lines, but this reform was nevertheless by 2013 widely supported within Fiji (Boege et al 2013). Nor would any of the various proposed voting systems prevent communal attachments from influencing electoral allegiances. Indeed, to prohibit this kind of voting would be impossible under any form of democracy, although bans on allegedly ethnic parties have been a frequent resort of military regimes claiming to transcend tribal divisions in Africa. Yet such was the political climate that many of the submissions to the FCC review, and during the government’s 2013 deliberations, extolled the virtues of this or that electoral system as ideally suited to eliminating ‘ethnic voting’. For similar reasons, New Zealand (or German) style mixed member PR was often unfairly rejected because it might entail two votes (one at the constituency level, and another for the party), a provision deemed to run counter to the ‘non-negotiable’ provision for ‘one person, one vote, one value’.

In February, Yash Ghai’s partner Jill Cottrell explained the FCC’s rejection of open list PR as sensible because ‘research shows that all open list systems tend to encourage voting on ethnic lines’ (Cottrell 2013), a claim that was hard to reconcile with the evidence from open list-using countries like Finland, Brazil or Indonesia in 2009. After the government released its new constitution in September, a common protest was that open list PR was inconsistent with the government’s ‘non-negotiable’ objectives. ‘Nothing in the Fiji Government Constitution restricts ethnic voting’, protested the Citizen’s Constitutional Forum. ‘When voters can choose who to vote for on open party lists, especially given Fiji’s history, they are likely to vote along the usual ethnic lines’ (CCF 2013b, p26, Fiji Times, 23 Sept 2013).

This implied that if closed list PR had been selected, as the FCC had proposed, party elites would be more likely to select politicians on a non-ethnic basis, a claim that might equally be doubted on the basis of Fiji’s troubled political history. After all, Fiji’s use of ‘above-the-line’ or ‘ticket voting’ at the 1999, 2001 and 2006 polls granted considerable control to political parties over which candidates were elected, without thereby encouraging selection of MPs particularly disposed to bridging the ethnic divide. Indeed, Fiji’s ticket voting provision borrowed an institution from the Australian Senate, where it is sometimes seen as transforming preferential voting into something similar to a closed list PR system (Sawer 2005: 286). In fact, the main scholarly debate amongst political scientists has been between those who believe all PR systems foster ethnicized voting (Horowitz 1985) and those who contest this (see Lijphart 2004; Huber 2012). Much less research has focussed on the difference between open and closed list systems in part because the borderline is often hazy (many countries have ‘semi-open’ or ‘flexible’ lists, as in the case of the Netherlands or Indonesia at the 2004 election).

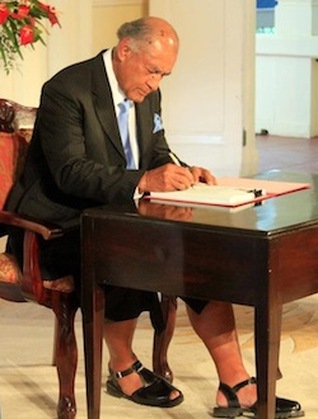

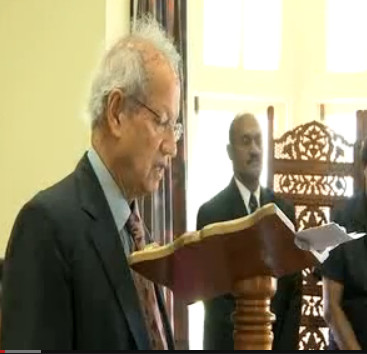

The first line of the new constitution reads ‘We the people of Fiji… hereby establish this constitution for the Republic of Fiji’. Such phrasing is more usually reserved for settings where there has been considerable public engagement in the process of constitutional design. As Randall Powell, one of the judges on the Fiji Court of Appeal who in April 2009 declared the Bainimarama government unconstitutional, pointed out ‘the draft Constitution has not been put to a referendum. It's been imposed on the people’ (ABC Pacific Beat, 23 Aug, 2013). Amnesty International said the constitution fell ‘far short of international standards of human rights law’ (Amnesty International, 2013), while Human Rights Watch said that it represented a ‘major step backwards’ (HRW, 2013). Yash Ghai doubted whether Bainimarama had actually read the constitution, and claimed that he usually ‘just repeats what his Attorney General tells him to say’ (Australian Network TV, 23 Oct 2013). Within Fiji, the SDL, or SODELPA, the Fiji Labour Party and the National Federation Party opposed the new constitution. Under the auspices of the United Front for a Democratic Fiji (UFDF), these parties wrote a letter of protest to the President, but none looked likely to boycott the 2014 elections. On the day of the presidential assent, a small crowd of protestors gathered to denounce the new constitution, and fourteen were temporarily taken into custody.

Some within Fiji praised the new legal framework. The Tui Tavua, Ratu Jale Waisele Kuwe Ratu, was particularly supportive, as were 1987 coup leader Sitiveni Rabuka (Fiji Sun, 25 Aug, 2013) and Fiji’s High Commissioner in London, Solo Mara (Mara 2013). One of the FCC commissioners, Satendra Nandan, inelegantly applauded Bainimarama’s achievement, through the ‘subtle force of arms’, of an end to ‘communal constituencies, racial categorisation, colonial hierarchies, feudal patriarchy, discrimination and dispossession of many kinds, coupled with inventions of traditions and institutions to rule rather than to serve’ (Nandan 2013).

More eloquently, those at the apex of the now formally disbanded chiefly order expressed a pervasive sense of victimization amongst Fiji’s once-powerful traditional rulers. Rewa chief Ro Teimumu Kepa and Cakaudrove’s Ratu Naiqama Lalabalavu issued a statement denouncing the ‘interim military government’ for ‘failure to protect the group rights of indigenous Fijians’, for usurping control over ‘native Fijians semi autonomous government (Matanitu Taukei)’ and for trashing the Yash Ghai draft constitution (Naiqama & Kepa 2013). Amongst those chiefs there were some signs of preparedness to make necessary political adjustments in order to confront the imposed new order. At the first gathering of the freshly rebranded SODELPA in June, party president Ro Teimumu saluted all three of Fiji’s deposed Prime Ministers, including Dr Timoci Bavadra (deposed 1987), Mahendra Chaudhry (deposed 2000) as well as Laisenia Qarase (deposed 2006) (Coup 4.5, 23 June 2013).

Chiefly institutions had been much weakened since the coup. The Great Council of Chiefs had not been allowed to meet since 2007, and it was formally disestablished in 2012. In 2010, government had changed the formula governing disbursal of rents obtained by the i-Taukei (formerly Native) Land Trust Board (TLTB). After deduction of 15% for administration, income had formerly been distributed to Fijian chiefs at various levels (15% to the turaga ni mataqali, 10% to the Turaga ni Yavusa, and 5% to the Turaga ni taukei), with the remaining 70% going to ordinary members of the mataqali (lineage or clan). New regulations in December 2010 provided instead that rents ‘shall be distributed by the Board to all the living members of the proprietary unit, in equal proportion’ (Fiji Government 2010).

Three years on, the practical impact of that ostensibly egalitarian reform was difficult to fully gauge accurately, but a requirement from 2012 that rents be paid electronically into bank accounts slowed down disbursals. TLTB General Manager Alipate Qetaki admitted in June 2013 that there were 30,000 landowners without bank accounts, that the board was finding it difficult to accurately establish how many living and deceased members of the mataqali should actually receive payments, and that unpaid rentals were accumulating at a rate of F$5 million a month (FBC 9 June 2013). Many of those who do hold bank accounts are anyway chiefs, and the effort to eliminate the role of traditional leaders was thus always likely simply to empower some alternative middle-men. In November, Bainimarama implicitly acknowledged problems when he publicly criticized TLTB ‘lethargy’ and said that ‘equal distribution will be fully implemented and automated by the beginning of next year’ (Fiji Sun 6 Nov 2013). The underlying dilemma may not be susceptible to a narrowly technological solution.

Whatever the truth about broader rental disbursals, indigenous chiefs from Western Viti Levu and the Macuata region of Vanua Levu, who were formerly recipients of substantial incomes from sugar cane farm leases, have lost major sources of income, and some of these chiefs are now being forced to earn a living by other means. Ironically, the eastern chiefly elite – Bainimarama’s main focus of attack – are less affected because TLTB rental incomes have never been vast in these parts of the country. More broadly, there is nowadays less incentive to speedily resolve title disputes. Of the 1,305 turaga ni yavusa (heads of clans) in Fiji, the iTaukei Lands and Fisheries Commission revealed in October that 544 remain vacant (42%). Of the 4,348 turaga ni mataqali (heads of lineages) in Fiji, 2,189 were not filled (50%) (Fiji Sun, Oct 27 2013, translation follows Toren 1999: 183). This prevalence of vacant titles should not necessarily be seen as signifying an erosion of the chiefly order. Often, those functioning in traditional roles – albeit uninstalled – assume positions that entail de facto recognition of the customary framework, even if the formal succession is contested.

Chiefs such as Ro Teimumu Kepa and Ratu Naiaqama Lalabalavu were not only angered by government reforms to rental disbursal, but also by efforts to acquire native lands for Bainimarama’s ‘land bank’. Harking back to the 1874 Deed of Cession to the British Crown, they reminded Fiji’s citizens of ‘government’s treaty obligation to our ancestors and to our chiefs in exchange for … surrendering the sovereign authority of these lands’. In retaliation for the imposition of the 2013 constitution, they suggested that ethnic Fijians in government should ‘cut off their connection with their native groups’ and delete their ‘names from their respective VKB [Vola ni Kawa Bula – Register of Native Births] of mataqalis, Yavusas and tribes’ (Naiqama & Kepa 2013).

The reaction to the new constitution from the Australian and New Zealand governments reflected a wider rapprochement that gathered pace through 2013. Australia’s Bob Carr ‘welcomed’ the new constitution (Carr 2013), while New Zealand Prime Minister John Key said that the immunity provisions were not a ‘deal-breaker’ (New Zealand Herald, 2 Sept 2013). By now, both Canberra and Wellington were aware that their travel sanctions were having negligible impact on Fiji’s coup-makers, beyond generating hostility to Australia and New Zealand. There was also a palpable sense of irritation, amongst many diplomats, that so much time was being taken up by Fiji-related affairs. Britain and the USA, as well as other regional players, were critical of the policy stance towards Fiji of their Southern Hemisphere allies, although the credibility of British foreign policy was rather besmirched when a Panorama sting operation exposed a Tory MP, Patrick Mercer, accepting £4,000 to press in the British parliament for Fiji’s readmission to the Commonwealth (The Times, 1 June 2013. £1 is equivalent to US$1.66). After 2010, Australian think-tanks, such as the Lowy Institute and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, devoted much energy to drawing attention to Fiji’s closer ties with China and the associated loss of Australasian regional influence, with the objective of encouraging an accommodation with the Fiji interim government.

Ultimately, the real driver of Australian policy realignment was developments within Fiji, even if this was not always obvious to the diplomats themselves, or to the Australian think-tanks which had become more vociferous in almost exact proportion to the quietening down of criticism from within Fiji. Whereas Fiji had witnessed a succession of severe crises in the three years immediately following the coup - including public sector strikes in 2007, threats of a Methodist uprising and the interim government’s breach with Mahendra Chaudhry’s Labour Party in 2008, the abrogation of the constitution in 2009, and schisms in the military senior command in late 2010 - since 2011 the domestic situation had stabilised. Meaningful change now looked less likely to come from another crisis or an insurrection, and more likely to follow the regime’s own July 2009 roadmap towards elections in 2014, if these were to be credible. Both the Australian and New Zealand governments – rightly or wrongly – anticipated that Bainimarama would win that election, and they wanted to better position themselves for its aftermath.

Forging closer ties with Fiji was not straightforward. Following the signing of an official ‘agrément’ in December 2012, Bob Carr announced that Margaret Twomey would be Australia’s next High Commissioner to Fiji (filling a position vacant since the expulsion of James Batley in 2009) (Dobell 2013). Yet Fiji soon reneged on that arrangement. When Carr commented that Fiji was ‘diminished’ by not accepting the appointment, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum accused Canberra of being ‘prescriptive and highhanded’ (Sayed-Khaiyum 2013) and Bainimarama told Radio Tarana ‘they don't treat us with consideration and respect, and I can assure you it's the same with all the Melanesian countries’ (Australia Network TV, 27 July 2013). Such criticisms struck a chord amongst Pacific leaders, and earned Bainimarama some popularity across the region.

During 2013, Fiji’s Prime Minister seized every opportunity to embarrass Australia and New Zealand, perhaps well advised that to do so would likely bring favourable results. One week after the withdrawal of the decade-old military component of the Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands, he took over a hundred military and police officers to the Solomon Islands for July 7 independence celebrations. ‘We have Fijian civilians present at many levels to assist your efforts at nation building’, Bainimarama told the luncheon gathering in Honiara: ‘be assured that Fiji stands willing and ready to take that assistance to another level with more personnel and resources, if that is the wish of the Government and people of Solomon Islands’ (Bainimarama 2013d). He did not mention that nearly all of those Fiji citizens working in the Solomon Islands were opponents of the 2006 Fiji coup, often deposed public servants who had fought with Bainimarama, left Fiji and found themselves senior positions overseas (part of a post-2006 diaspora of dissident Fiji professionals that was evident across the Pacific Islands). The barely concealed challenge to Australia was that Fiji might provide foot-soldiers for the occasionally anticipated Melanesian rapid deployment force, though the big unanswered question was who would pay for this.

Speaking at the Australia-Fiji Business Forum in Brisbane in late July, Fiji Foreign Minister Ratu Inoke Kubuabola criticized ‘behaviour on the part of the Australian Government that is inconsiderate, prescriptive, highhanded and arrogant’ (Kubuabola 2013). Australian opposition spokesperson for foreign affairs Julie Bishop was in the audience. She spoke later that day acknowledging Kubuabola’s ‘very powerful speech’ and said it was ‘refreshing to hear the frustration that the Fijian Government feels about Australia’s approach’. For now, Labor was still in office in Canberra, but it was well known that the Liberal-National coalition was likely to win the September election. As Bishop told the forum, ‘normalising relations between Australia and Fiji is a priority of an incoming [Coalition] government’ (Bishop 2013).

In August, much attention was focussed on the inaugural meeting of the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF) hosted by Bainimarama in Nadi, and attended by East Timorese Prime Minister Xanana Gusmao, the Prime Minister of the Solomon Islands, and the Presidents of Nauru and Kiribati (Tarte 2013). In a thinly-veiled critique of the Pacific Islands Forum, from which Fiji remained suspended through 2013, Bainimarama promised the that the new grouping would be the ‘antithesis of most bureaucracies’ and would not have an ‘army of overpaid officials’ (Bainimarama 2013e). Indeed, Bainimarama now said Fiji would not rejoin the Pacific Islands Forum unless major organizational changes were made to the region’s established political architecture (RNZI 13 Sept).

Fiji’s 2013 Pacific diplomacy was not always plain sailing. In his Brisbane business forum speech, Ratu Inoke Kubuabola said his government was ‘decidedly less than happy’ with the Australian arrangements to ‘dump’ asylum-seekers on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, and demanded ‘thorough regional consultation’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 30 July 2013). Instead of travelling to the Pacific Islands Development Forum in Nadi in August, offended PNG Prime Minister Peter O’Neill instead undertook a state visit to New Zealand. Only days later, a deal for Vodafone (Fiji) to take over the management of PNG’s Bemobile collapsed (The National (PNG), 6 Aug 2013). In October, Fiji Television Ltd moved to relinquish its stake in PNG’s EMTV station after Peter O’Neill’s government said it was preparing new media ownership legislation (Islands Business, Oct 2013). And the fallout continued. In December, the Fiji government refused to accept the appointment of PNG High Commissioner, Peter Eafeare, as Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, despite his being the most senior foreign representative in Suva (Post-Courier (PNG), Dec 9, 2013).

Yet this PNG-Fiji feud was neither long-lasting nor too disruptive of ongoing business linkages. Despite the diplomatic difficulties, PNG agreed to deliver F$50 million assistance for Fiji’s 2014 polls. In August, PNG investors acquired the Pearl Resort, and the nearby golf course, for F$32 million and soon afterwards announced a major refurbishment and extension of the Pacific Harbour marina (Fiji Sun 19 Aug, 4 Nov 2013). As funds start to flow from its Southern Highlands liquid natural gas and other mineral resource developments, PNG is increasing its investments across the Pacific region.

Fiji’s economy experienced a third year of recovery in 2013. The IMF estimated real GDP growth at 3% for the year, and inflation was down to 2.9% after averaging 6% per annum over the previous five years (IMF 2013, see also ADB 2013a, 2013b). Sugar output had reached a trough below 150,000 tonnes in 2010, half the level of a decade earlier, but performance stabilized over 2011-13 with a new leadership team at the Fiji Sugar Corporation, and technical assistance from the now American-owned company Tate & Lyle. That company purchased four of Fiji’s five shipments of sugar in 2013 for its refinery on the banks of the River Thames in London.

In March, Mauritian Tate & Lyle consultant Dan Boodhna told Tagitagi famers near Navua that ‘at an average of 40 tonnes per hectare, Fiji has the lowest production per hectare in the world’, partly due to increasing acidity in the soils (Fiji Times 13 March 2013). Other problems too have affected the quality of cane delivered to the mills. Burning cane before harvesting has been increasing in Fiji for many years, particularly since the late 1980s, partly to ease cane-cutting, partly to eliminate rodents and hornets and above all, more mischievously, to jump the queues for supplying cane to the mills (Davies 1998: p14-15). In September, Police Commissioner Brigadier General Ioane Naivalurua and Sugar Ministry permanent secretary Lieutenant Colonel Manasa Vaniqi announced a new programme of police deployment on horseback to halt fires in the cane fields (Fiji Times, 5 Sept, 2013). A more major threat to the industry is the loss of duty-free access to European markets. In June, Bainimarama – in his capacity as chair of the International Sugar Organization – called for the extension from 2015 until 2020 of European Union duty free quotas for the African Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries (Fiji Times, 5 June, 2013).

The year saw further strengthening of Fiji’s ties with China. In May, Bainimarama travelled to Beijing and met Chinese President, Xi Jinping (Fiji government 2013d). Lieutenant General Wang of the People’s Liberation Army was hosted at the Sofitel resort near Nadi in August, and three months later a reciprocal delegation of senior military officers accompanied Defence Minister Joketani Cokanasiga to China (Islands Business, 28 Aug 2013, ABC, 27 Nov 2013). 300 of Fiji’s civil servants are scheduled to travel for training to China over a three-year period.

Closer diplomatic ties have assisted the expansion of Chinese investment. In October, the Shandong Province headquartered Zhongrun International Mining Company moved to acquire a controlling stake in Vatukoula Gold Mines on northern Viti Levu, and announced a F$40 million investment package pending approval from Chinese foreign exchange authorities (Fiji Sun, 5 Mar, Fiji Sun 4 Oct 2013). The Chinese-owned bauxite mine in Bua on Vanua Levu exported 700,000 tonnes in twelve shipments earning Fiji around F$28.8 million in 2013 (Fiji Times 19 Dec 2013, Fiji Times 20 Dec 2013). The long-gestating China Railway First Rawai housing project ran into difficulty early in 2013, but was resuscitated after intervention by the Prime Minister secured an additional F$9.3 million grant from the government in Beijing to complete the work (FijiLive, 30 Sept, 2013).

The link with China was potentially politically sensitive. When Bainimarama announced an intention to change the Fiji flag so as to remove the British Union Jack from its top left corner in January, Catholic priest Kevin Barr – once a vocal supporter of Bainimarama’s poverty alleviation reforms – wrote in jest to the Fiji Sun that this might be replaced with the Chinese flag. That triggered Bainimarama to hurl a torrent of expletives at the disenchanted priest over the telephone, and afterwards to threaten him with deportation (The Australian, 18 Jan 2013). The embarrassed Barr soon rediscovered his humility, and was allowed to remain in Fiji.

Fiji’s government was more ruthless in dealing with its longer standing enemies. Deposed Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase was released from prison in April, having served seven months. An appeal against his conviction was quashed in May (Fiji Times, 31 May 2013). That barred him from contesting elections, and drove the SDL/SODELPA to seek a new leader. Further charges against Qarase brought by the Fiji Independent Commission against Corruption were in the pipeline (Fiji Sun, 4 June 2013), transparently aimed at destroying his political career. Labour leader Mahendra Chaudhry, who served as Finance Minister under Bainimarama during 2007-8, was also brought before the courts in 2013 on charges of financial irregularities (RNZI 16 May 2013, Fiji Sun, 26 Feb, 2014). The Bainimarama government had shown itself quite prepared to drop such cases when rivals relinquished aspirations to hold public office, as in the case of former Chief Justice Daniel Fatiaki in December 2008. The treatment of dissident soldiers was more unforgiving. Pita Driti, the Land Force commander who was alleged to have plotted against Bainimarama and Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum in 2010 had since sought to make his peace with the regime, but he was nevertheless sent to prison in December 2013 for five years.

In March, Bainimarama casually announced his intention to stand for elections from the running track of the new ANZ stadium in Suva (Fiji TV, 22 March 2013), and he promised to stand down as Commander of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces in early 2014. The Prime Minister courted conservative indigenous support by denouncing same-sex marriage, and promising strong legal protections for indigenous land rights (Fiji Sun, 27 Mar 2013, RNZI, 3 May 2013). In September, he authorized the Public Services Commission to agree substantial pay rises for top civil servants. The Fiji Trades Union Congress reported a trebling of salaries from F$75,000 to F$221,894 for the permanent secretaries in the Prime Minister’s office, finance, education, health and works, an increase from F$60,000 to F$160,000 for other permanent secretaries, and a rise from F$160,000 to F$221,894 for the military commander, and the chiefs of police and prisons (Fiji Times, 24 Sept, 2013). In November, cross-the-board pay rises were announced for the civil service of between 10-23% (FijiLive, 8 Nov, 2013), which dissident economist Wadan Narsey described as ‘a blatant “vote-buying” tactic’ (Narsey 2013). The 2014 budget included a substantial rise in government expenditure - with large provisions for road-building - and unlikely plans to finance these through F$475 million in sales of state assets. Youths demonstrating on the occasion of the budget announcement sporting T-shirts adorned with the slogan ‘C’mon Fiji – Make Budgets Public now’ were briefly taken into custody (ABC, 8 Nov, 2013).

The Fiji Sun claimed great public support for Bainimarama, but critics warned that liu muri (’”deceitful”, literally “front-back”) voters might say one thing publicly, but do another at the polls. Certainly, people in Fiji seemed keen that there be an election. During 2013, over half a million signed up using the new biometric registration system, an estimated 87% of those entitled to do so. With the voting age reduced from 21 to 18, and the new dual nationality provisions enabling many overseas to register, the 2014 polls promised to be very different to Fiji’s earlier elections. In the past, tiny communal electorates had their own MPs, and district design overall favoured rural communities. With a single nationwide constituency, the historical bias against Fiji’s urban population was at last removed. Some analysts believe that Bainimarama’s party is likely to perform well in the rural areas but will ‘struggle to win the support of the urban middle class who felt victimized by the coup’ (Steve Ratuva, cited in Fiji Sun, 23 May 2013), a verdict opposite to that offered by the Pacific Theological College's survey (see above). Others consider that the election itself will be a sham.

And still others point to the great difficulty Bainimarama and his government have experienced with dialogue processes, and question whether military leaders and their acolytes can easily or effectively make the transition to civilian politics, build a political party and venture onto the campaign trail. Deliberations over the new legal framework in 2012 and 2013 had brought ‘hope and expectations’, concluded Fiji’s former Vice President, Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi, ‘which may generate a great deal of momentum that the government may eventually be unable to control’ (Madraiwiwi 2013). Whichever way, more worryingly, the post election government will face a 2013 constitution that cannot easily be changed by democratic methods. - MARCH 2014

Fijileaks Editor: What is posted here is an "preprint" manuscript version of a political review to be published by the University of Hawai'i Press in The Contemporary Pacific 26:2 (September 2014).