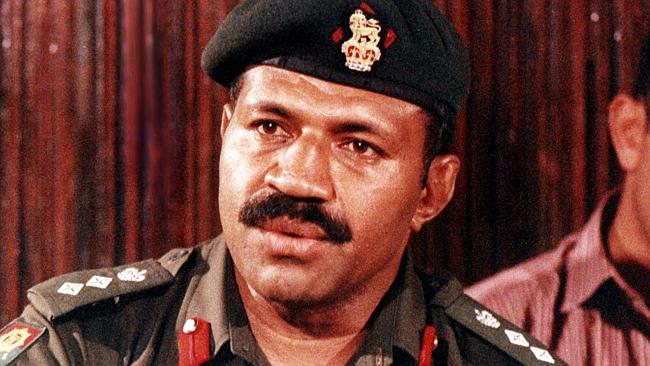

Fijileaks: We support Ratu Isoa Tikoca's courageous and forthright demand at the recent SODELPA annual general meeting when he stood up and told the stunned audience that SITIVENI RABUKA should be REPLACED by RO TEIMUMU KEPA, for Rabuka was an election liability; we will also reveal how Ratu Naiqama and Adi Litia BETRAYED Ro Kepa and dumped RABUKA onto SODELPA rank-and-file members

A lengthy revelation on the land sale closer to the 2018 general election

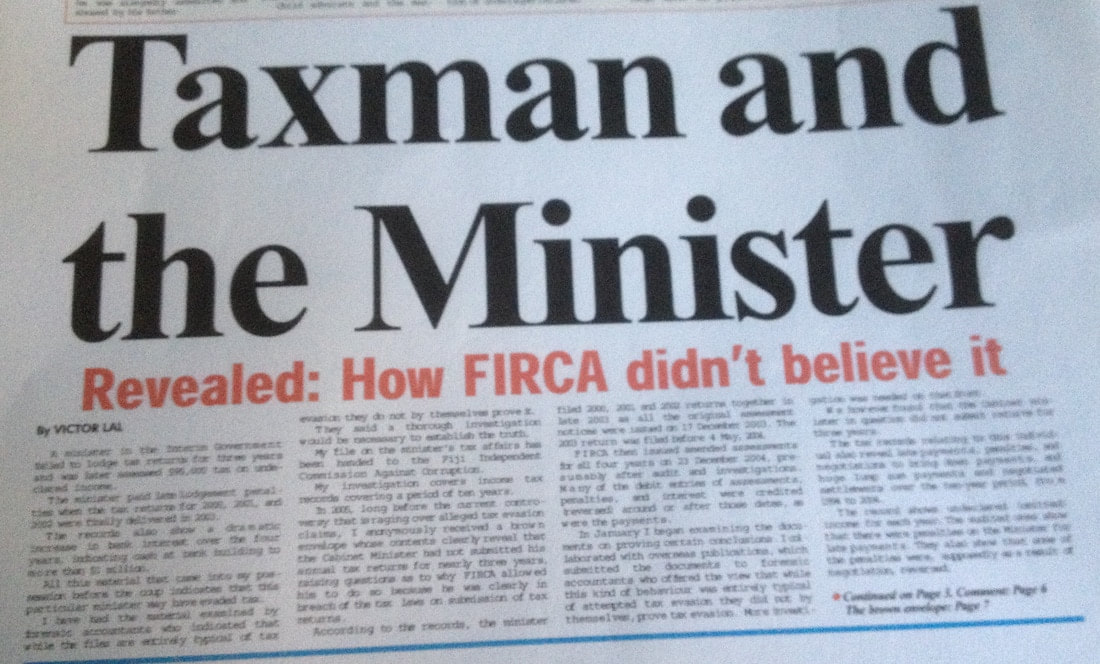

And how he and his racist thugs bankrupted the National Bank of Fiji as if it was their MONEY - all in the name of bogus i-taukei affirmative action

The NBF was ordered by the then Rabuka government to grant “soft loans” to the “downtrodden” taukei population. The rationale was that the taukei created instability in the country because they were economically disadvantaged, and the way to prevent future instability was to narrow the gap between their economic position and others by introducing affirmative action policies.

Flawed though this reasoning was, and based on no reputable statistics, the program was immensely popular among the ordinary taukei, and who can blame them.

Since the principle of handouts was based only on ethnicity, it provided the basis of a bank policy of soft loans with few questions asked. Between 1987 and 1994, more than $200 million was lent to prominent individuals and businesses on the basis of no or inadequate securities. No one noticed what was happening. The borrowers did not pay the loans back.

When that loans scandal broke there was an investigation into the NBF, firstly by the Reserve Bank, secondly by the Ministry of Finance, and thirdly by the police. The findings were shocking to our senses: $200 million in unsecured or under-secured loans. The beneficiaries were not the disadvantaged taukei. And no loan was likely to be repaid. Police investigations revealed fraud, corruption, and gross abuse of office, obtaining money by false pretences and obtaining credit by fraud.

Of course the first question asked was where were the watchdogs? How could this happen with a strong parliamentary opposition, an Auditor-General, a free media, a banker’s bank (The Reserve Bank) and a watchdog - the Ministry of Finance? It became painfully apparent, as those who made a study of it have pointed out, that none of these “good governance” institutions had the capacity to stop the stinking rot.

The jury is still out on whether they all knew what was going on, and failed to intervene in a politically supported hot ‘lovo’. But the institutions failed to detect or expose the fraud, until it was too late.

And so the taxpayers turned to the criminal justice system to demonstrate accountability. Police investigations took almost three years to complete. The Fiji Police Force was under-trained and under resourced, and fraud laws antiquated. The investigations were compounded because DPP’s Office, which was destroyed in the 1987 coup, was staffed with under-qualified and inexperienced lawyers. The National Bank prosecutions, led by the then Director of Public Prosecutions, later Justice Nazhat Shameem, were a test of the ability of Fiji’s criminal justice system to try the rich and the powerful. She had already held that office for some three years.

Those of us who eagerly and closely followed the whole saga soon noticed a sinister pattern emerging, prevalent in many other corruption riddled Third World countries. The first was the hostility of the magistracy. State prosecutors were daily maligned, abused, and on one occasion detained in custody for alleged contempt of court. In one absurd case the accused, who was a Cabinet Minister and a high chief, had been permitted to sit at the bar table instead of the dock.

His counsel, in the course of the preliminary inquiry abused the prosecutor on the basis of his skin color. He was an Australian and the Deputy DPP. The Fijian magistrate reprimanded the prosecutor for insulting Fijian culture when he (the prosecutor) led evidence that the accused had received large sums of money “for his people” in exchange for fishing licenses. When the prosecutor tried to present his side of the story, he was detained in the police cell for “contempt of court”, raising the question: when does a cultural gift become a corruptly received gift?

We might recall that the DPP Shameem had to appear to secure his release, and to request the magistrate to disqualify himself. He refused to do so. Shameem moved the High Court to order him to disqualify himself. The High Court did so order, but the defence appealed that decision to the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court. So much delay ensued, that the trial of the Minister never proceeded. The DPP, who took office after Shameem left, entered a nolle prosequi. The prosecutor won the battle, but the war was lost.

In the midst of the judicial battles, came the interlocutory challenges. The prosecution tried to ground all the accused by seizing their passports. Their lawyers and the magistrates were outraged. These were important people: Cabinet Ministers, lawyers, and businessmen. In vain the prosecution argued that all suspects should be treated in the same way, and their travelling curtailed. When the prosecution failed, it appealed the bail rulings to the higher courts. Again, the delay worked to its detriment. The prosecution got so caught up in interlocutory hearings that the substantive matters were never aired.

In the few cases that did proceed to trial, witnesses refused to testify. When they gave evidence, they turned hostile. They agreed to everything suggested to them by the defence. A lawyer who had told the police that the signature on a cheque was that of his partner (the accused) said on evidence that he was mistaken and that in fact the accused had been out of the country at the time. One after another, Ministers, senior bank officials, lawyers and businessmen were acquitted. The impatient media, having failed to notice the “cat and mouse” legal game, began to unnecessarily criticize the DPP’s Office.

It only rallied to Shameem’s defence when someone leaked to the press the behind the scenes strong-arm tactics that was being deployed against her. In the midst of the hearings, the Public Service Commission had asked her to sign a performance agreement, which would have made her accountable to the Permanent Secretary for Justice.

She refused to sign. The Commission complained to the Chief Justice. She refused to sign. The matter was discussed in the Judicial Services Commission (the appointing body of the DPP). She refused to sign. Cabinet ordered her to sign and expressed “concern” at her refusal to co-operate with the authorities. She refused to sign. When things began to look very ugly, the matter was leaked to the media, which was forced to rally to her support.

Then personal attacks were rained on her. It later emerged that she received abusive memoranda from senior public servants who refused to accept any correspondence from her without approval from the Minister of Justice and Attorney-General. One memorandum expressed the view that she was unfit to hold public office.

The Attorney-General refused to send her requests for mutual assistance from Australia and New Zealand for witnesses to give evidence on video link. Overnight, the Ministry of Finance cut her department’s budget by 40%. The vote most affected was the witness expense vote. She could no longer afford to summon witnesses. It was restored only when she threatened to challenge the decision of the Minister of Finance in court. The end result was that despite the prosecution’s best efforts, no one was convicted. The courts in the NBF scam held no one accountable.

No doubt, many would call that a failure. In one sense it was a failure. It was the failure of Fiji’s democratic and judicial institutions to tackle corruption and give effect to the rule of law. Clearly, the law could not hold the rich and powerful to account for their conduct.

However, that view is too simplistic. Firstly the police investigations and the prosecutions themselves provided a form of accountability. Chiefs, who had never before been asked what they did with the money they received for their people, had to explain themselves. So did Cabinet Ministers, including lawyers. In order to achieve their acquittals, they had to pay vast sums of money to their lawyers.

Secondly, the prosecutions confronted the inequities in the judicial system. The Judicial and Legal Services Commission disciplined the magistrate, who detained the prosecutor. Another, who cited a newspaper reporter and a prosecutor for contempt, was maligned and savagely attacked in the newspapers. The government machinery, which had with ease silenced many independent officers with threats and administrative heavy-handedness, was unable to silence Shameem as head of the prosecution team. Her office grew in strength.

And it took on a wider public interest role.

The third positive aspect of the story of the National Bank was the role of the media. The media discovered the scandal. A list of names of people who owed money to the Bank was published in one of the newspapers. For the first time, the media realized that Shameem’s struggle was one to preserve the rule of law in an ailing democracy.

Their stories became much more discerning and informed. The government failed to “shoot the messenger” – in this case Nazhat Shameem, who tried to bring to justice the nations “corruptodiles”.

It is therefore important that the present anti-corruption hunters must not be allowed to suffer the same trials and tribulations experienced by Shameem and her legal team, for corruption is the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.

The National Bank of Fiji story showed the inability of Fiji’s institutions to deal with a gross abuse of public office for private gain.

There is no doubt that any investigations in the NBF saga would have been conducted if it had not been for the public outcry. There was an outcry as a result of the strength, perseverance and integrity of Fiji’s media. And the investigation process followed because the political process made it too difficult not to show some signs of accountability.

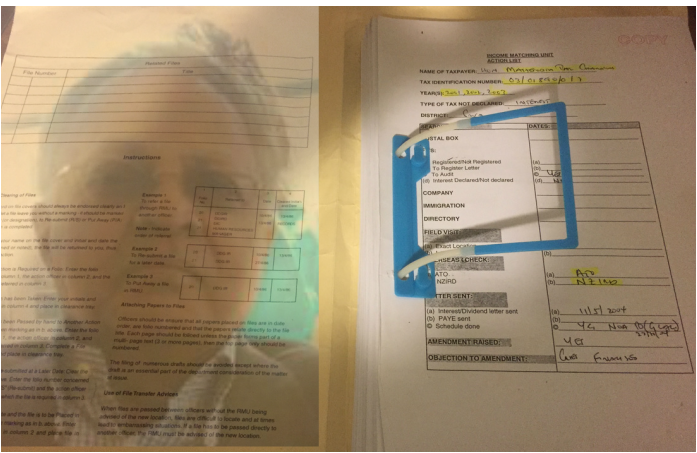

The investigation of the National Bank of Fiji was hampered by witness reluctance, police resource limitations, missing files and documents and archaic criminal laws.

Flawed though this reasoning was, and based on no reputable statistics, the program was immensely popular among the ordinary taukei, and who can blame them.

Since the principle of handouts was based only on ethnicity, it provided the basis of a bank policy of soft loans with few questions asked. Between 1987 and 1994, more than $200 million was lent to prominent individuals and businesses on the basis of no or inadequate securities. No one noticed what was happening. The borrowers did not pay the loans back.

When that loans scandal broke there was an investigation into the NBF, firstly by the Reserve Bank, secondly by the Ministry of Finance, and thirdly by the police. The findings were shocking to our senses: $200 million in unsecured or under-secured loans. The beneficiaries were not the disadvantaged taukei. And no loan was likely to be repaid. Police investigations revealed fraud, corruption, and gross abuse of office, obtaining money by false pretences and obtaining credit by fraud.

Of course the first question asked was where were the watchdogs? How could this happen with a strong parliamentary opposition, an Auditor-General, a free media, a banker’s bank (The Reserve Bank) and a watchdog - the Ministry of Finance? It became painfully apparent, as those who made a study of it have pointed out, that none of these “good governance” institutions had the capacity to stop the stinking rot.

The jury is still out on whether they all knew what was going on, and failed to intervene in a politically supported hot ‘lovo’. But the institutions failed to detect or expose the fraud, until it was too late.

And so the taxpayers turned to the criminal justice system to demonstrate accountability. Police investigations took almost three years to complete. The Fiji Police Force was under-trained and under resourced, and fraud laws antiquated. The investigations were compounded because DPP’s Office, which was destroyed in the 1987 coup, was staffed with under-qualified and inexperienced lawyers. The National Bank prosecutions, led by the then Director of Public Prosecutions, later Justice Nazhat Shameem, were a test of the ability of Fiji’s criminal justice system to try the rich and the powerful. She had already held that office for some three years.

Those of us who eagerly and closely followed the whole saga soon noticed a sinister pattern emerging, prevalent in many other corruption riddled Third World countries. The first was the hostility of the magistracy. State prosecutors were daily maligned, abused, and on one occasion detained in custody for alleged contempt of court. In one absurd case the accused, who was a Cabinet Minister and a high chief, had been permitted to sit at the bar table instead of the dock.

His counsel, in the course of the preliminary inquiry abused the prosecutor on the basis of his skin color. He was an Australian and the Deputy DPP. The Fijian magistrate reprimanded the prosecutor for insulting Fijian culture when he (the prosecutor) led evidence that the accused had received large sums of money “for his people” in exchange for fishing licenses. When the prosecutor tried to present his side of the story, he was detained in the police cell for “contempt of court”, raising the question: when does a cultural gift become a corruptly received gift?

We might recall that the DPP Shameem had to appear to secure his release, and to request the magistrate to disqualify himself. He refused to do so. Shameem moved the High Court to order him to disqualify himself. The High Court did so order, but the defence appealed that decision to the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court. So much delay ensued, that the trial of the Minister never proceeded. The DPP, who took office after Shameem left, entered a nolle prosequi. The prosecutor won the battle, but the war was lost.

In the midst of the judicial battles, came the interlocutory challenges. The prosecution tried to ground all the accused by seizing their passports. Their lawyers and the magistrates were outraged. These were important people: Cabinet Ministers, lawyers, and businessmen. In vain the prosecution argued that all suspects should be treated in the same way, and their travelling curtailed. When the prosecution failed, it appealed the bail rulings to the higher courts. Again, the delay worked to its detriment. The prosecution got so caught up in interlocutory hearings that the substantive matters were never aired.

In the few cases that did proceed to trial, witnesses refused to testify. When they gave evidence, they turned hostile. They agreed to everything suggested to them by the defence. A lawyer who had told the police that the signature on a cheque was that of his partner (the accused) said on evidence that he was mistaken and that in fact the accused had been out of the country at the time. One after another, Ministers, senior bank officials, lawyers and businessmen were acquitted. The impatient media, having failed to notice the “cat and mouse” legal game, began to unnecessarily criticize the DPP’s Office.

It only rallied to Shameem’s defence when someone leaked to the press the behind the scenes strong-arm tactics that was being deployed against her. In the midst of the hearings, the Public Service Commission had asked her to sign a performance agreement, which would have made her accountable to the Permanent Secretary for Justice.

She refused to sign. The Commission complained to the Chief Justice. She refused to sign. The matter was discussed in the Judicial Services Commission (the appointing body of the DPP). She refused to sign. Cabinet ordered her to sign and expressed “concern” at her refusal to co-operate with the authorities. She refused to sign. When things began to look very ugly, the matter was leaked to the media, which was forced to rally to her support.

Then personal attacks were rained on her. It later emerged that she received abusive memoranda from senior public servants who refused to accept any correspondence from her without approval from the Minister of Justice and Attorney-General. One memorandum expressed the view that she was unfit to hold public office.

The Attorney-General refused to send her requests for mutual assistance from Australia and New Zealand for witnesses to give evidence on video link. Overnight, the Ministry of Finance cut her department’s budget by 40%. The vote most affected was the witness expense vote. She could no longer afford to summon witnesses. It was restored only when she threatened to challenge the decision of the Minister of Finance in court. The end result was that despite the prosecution’s best efforts, no one was convicted. The courts in the NBF scam held no one accountable.

No doubt, many would call that a failure. In one sense it was a failure. It was the failure of Fiji’s democratic and judicial institutions to tackle corruption and give effect to the rule of law. Clearly, the law could not hold the rich and powerful to account for their conduct.

However, that view is too simplistic. Firstly the police investigations and the prosecutions themselves provided a form of accountability. Chiefs, who had never before been asked what they did with the money they received for their people, had to explain themselves. So did Cabinet Ministers, including lawyers. In order to achieve their acquittals, they had to pay vast sums of money to their lawyers.

Secondly, the prosecutions confronted the inequities in the judicial system. The Judicial and Legal Services Commission disciplined the magistrate, who detained the prosecutor. Another, who cited a newspaper reporter and a prosecutor for contempt, was maligned and savagely attacked in the newspapers. The government machinery, which had with ease silenced many independent officers with threats and administrative heavy-handedness, was unable to silence Shameem as head of the prosecution team. Her office grew in strength.

And it took on a wider public interest role.

The third positive aspect of the story of the National Bank was the role of the media. The media discovered the scandal. A list of names of people who owed money to the Bank was published in one of the newspapers. For the first time, the media realized that Shameem’s struggle was one to preserve the rule of law in an ailing democracy.

Their stories became much more discerning and informed. The government failed to “shoot the messenger” – in this case Nazhat Shameem, who tried to bring to justice the nations “corruptodiles”.

It is therefore important that the present anti-corruption hunters must not be allowed to suffer the same trials and tribulations experienced by Shameem and her legal team, for corruption is the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.

The National Bank of Fiji story showed the inability of Fiji’s institutions to deal with a gross abuse of public office for private gain.

There is no doubt that any investigations in the NBF saga would have been conducted if it had not been for the public outcry. There was an outcry as a result of the strength, perseverance and integrity of Fiji’s media. And the investigation process followed because the political process made it too difficult not to show some signs of accountability.

The investigation of the National Bank of Fiji was hampered by witness reluctance, police resource limitations, missing files and documents and archaic criminal laws.