"The 2000 coup and mutiny was due to incompetence and bad military leadership. Even if Frank Bainimarama was not aware (we believe he was aware), as Commander he should have suspected things. When the Commanding Officer 3FIR, Lt Colonel Viliame [Bill] Seruvakula took his intelligence team to Bainimarama a week before he left for Norway and briefed him about an impending coup, you know what happened? Bainimarama actually chased them out of his office.'

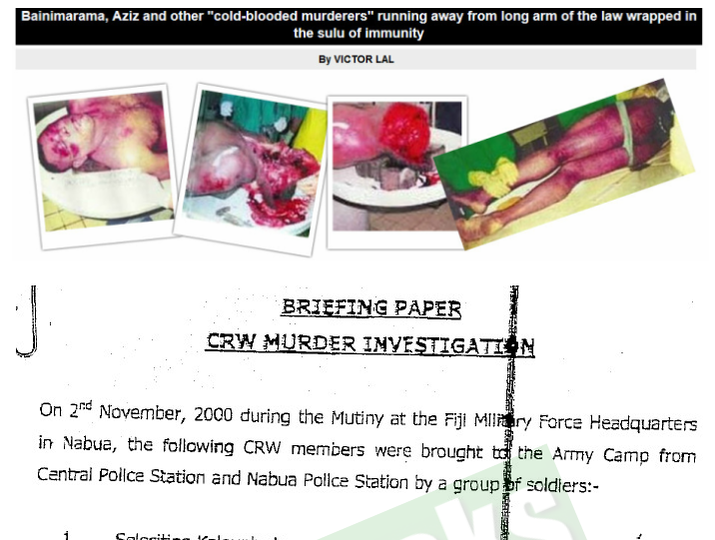

I HAVE read with great interest the RFMF Commander Ratu Jone Kalouniwai's version of what transpired during the 2 November 2000 mutiny. As I have pointed out on numerous occasions, the late Fiji Sun publisher Russell Hunter and I had been working on a book about the tragic events of 2000 and on the inside story about the 2006 coup.

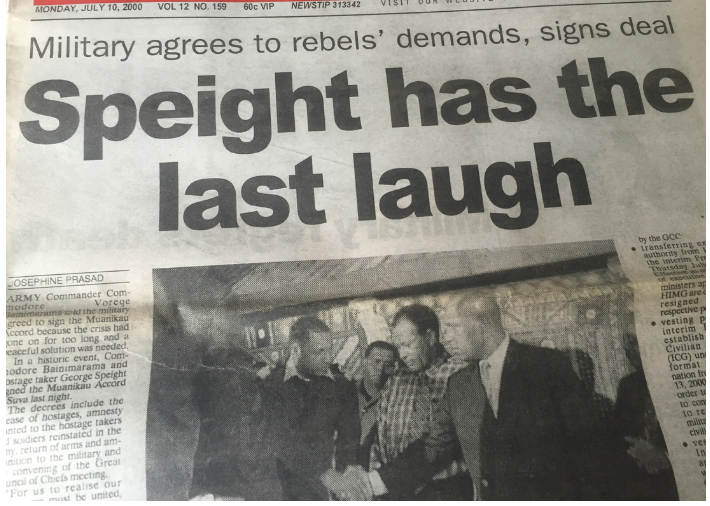

In 2000, I was closely involved in the lead up to the drawing up of the Muanikau Accord, and also wrote a lengthy legal treatise arguing that George Speight could be charged with TREASON because Speight had violated a particular section of the Muanikau Accord. Before Frank Bainimarama seized power on 5 December 2006, my military contacts at Berkley Crescent headquarters had leaked to me hundreds of highly classified military documents including the intelligence reports that was prepared by Kalouniwai and his team on the CRWU soldiers.

I still have them on me and which was to form part of the book - TREASON IN PARADISE: The Inside Story about 2006 Fiji Coup. The first completed chapter begins with the overthrow of the Chaudhry government, the role of the CRWU soldiers, their shadowy backers, and the 2 November 2000 mutiny. Hunter and I had interviewed several key military figures and had also confronted Colonel Jone Baledrokadroka, for his version of events were not in sync with other key military figures who had helped put down the bloody uprising that day.

In his recollection, Kalouniwai does not name the officer. According to his account: 'The unfortunate events of the day began after mid-day, together with a fellow officer; we were working on preparing an intelligence briefing for the Commander, highlighting intelligence indications of a possible palace coup within the RFMF.'

During the course of our lengthy investigation, we had established that the officer was MAJOR NIKO BUKARAU, brother of Lt Col TEVITA BUKARAU who was with George Speight. From the documents in my possession, Niko Bukarau ran the Force's Intelligence and Kalouniwai was under him. One rebel from the CRWU had refused to execute Bukarau and Kalouniwai at the height of the gun battle. Niko Bukarau, who escaped execution, told Fiji's Daily Post: "I should be in the mortuary if everything went as planned."

However, we know that Niko Bukarau was fervently against George Speight and the group, and Kalouniwai was aware of it. Unfortunately, there are a lot of gaps in Kalouniwai's version. So far, he has not mentioned that despite their pre-2000 coup briefings and warnings, FRANK BAINIMARAMA, as RFMF Commander, did not heed that.

The two million dollar question:

What was Sakeasi Butadroka doing in Queen Elizabeth Barracks on numerous occasions before he died (2 December 1999), urging Bainimarama to remove the President, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, and the Chaudhry government?

During the 2000 coup, and lead up to the Muanikau Accord, at one of the officer's gatherings at the Officers Mess, senior military officers led by Jerry Waqanisau, confronted Bainimarama and urged him not to give in. From our investigations those present included the current Speaker Ratu Epeli Nailatikau, so was the former Commander Ratu Epeli Ganilau and other senior officers.

In addition, why was Bainimarama insistent at the QEB Great Council of Chiefs meeting during the coup that the President, Ratu Sir Kamisese, RESIGN? He was openly urging Adi Litia Cakobau for that, according to our sources who were present at that meeting.

Now, it seems that Kalouniwai is allegedly blaming SITIVENI RABUKA while leaving out other highly significant players.

I am sure the late RUSSELL HUNTER would have urged me to put the record straight.

In 2000, I was closely involved in the lead up to the drawing up of the Muanikau Accord, and also wrote a lengthy legal treatise arguing that George Speight could be charged with TREASON because Speight had violated a particular section of the Muanikau Accord. Before Frank Bainimarama seized power on 5 December 2006, my military contacts at Berkley Crescent headquarters had leaked to me hundreds of highly classified military documents including the intelligence reports that was prepared by Kalouniwai and his team on the CRWU soldiers.

I still have them on me and which was to form part of the book - TREASON IN PARADISE: The Inside Story about 2006 Fiji Coup. The first completed chapter begins with the overthrow of the Chaudhry government, the role of the CRWU soldiers, their shadowy backers, and the 2 November 2000 mutiny. Hunter and I had interviewed several key military figures and had also confronted Colonel Jone Baledrokadroka, for his version of events were not in sync with other key military figures who had helped put down the bloody uprising that day.

In his recollection, Kalouniwai does not name the officer. According to his account: 'The unfortunate events of the day began after mid-day, together with a fellow officer; we were working on preparing an intelligence briefing for the Commander, highlighting intelligence indications of a possible palace coup within the RFMF.'

During the course of our lengthy investigation, we had established that the officer was MAJOR NIKO BUKARAU, brother of Lt Col TEVITA BUKARAU who was with George Speight. From the documents in my possession, Niko Bukarau ran the Force's Intelligence and Kalouniwai was under him. One rebel from the CRWU had refused to execute Bukarau and Kalouniwai at the height of the gun battle. Niko Bukarau, who escaped execution, told Fiji's Daily Post: "I should be in the mortuary if everything went as planned."

However, we know that Niko Bukarau was fervently against George Speight and the group, and Kalouniwai was aware of it. Unfortunately, there are a lot of gaps in Kalouniwai's version. So far, he has not mentioned that despite their pre-2000 coup briefings and warnings, FRANK BAINIMARAMA, as RFMF Commander, did not heed that.

The two million dollar question:

What was Sakeasi Butadroka doing in Queen Elizabeth Barracks on numerous occasions before he died (2 December 1999), urging Bainimarama to remove the President, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, and the Chaudhry government?

During the 2000 coup, and lead up to the Muanikau Accord, at one of the officer's gatherings at the Officers Mess, senior military officers led by Jerry Waqanisau, confronted Bainimarama and urged him not to give in. From our investigations those present included the current Speaker Ratu Epeli Nailatikau, so was the former Commander Ratu Epeli Ganilau and other senior officers.

In addition, why was Bainimarama insistent at the QEB Great Council of Chiefs meeting during the coup that the President, Ratu Sir Kamisese, RESIGN? He was openly urging Adi Litia Cakobau for that, according to our sources who were present at that meeting.

Now, it seems that Kalouniwai is allegedly blaming SITIVENI RABUKA while leaving out other highly significant players.

I am sure the late RUSSELL HUNTER would have urged me to put the record straight.

Fijileaks: In 2017, we had revealed that Kalouniwai was held hostage during the November 2000 mutiny. Now, he has confirmed our original story.

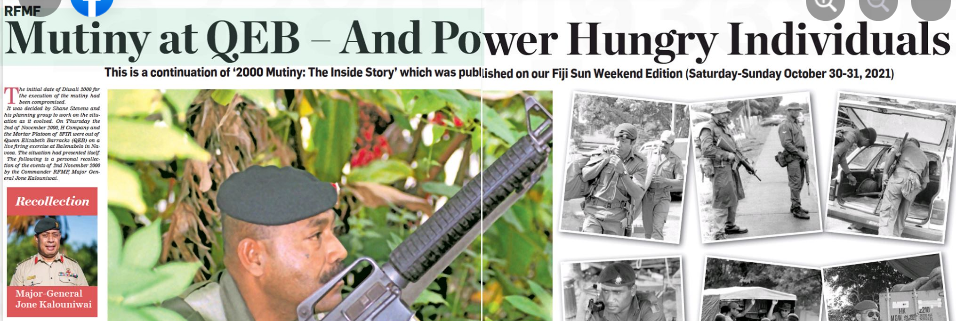

The following is a personal recollection of the events of 2nd November 2000 by the Commander RFMF, Major General Jone Kalouniwai. Source: The Fiji Sun

Lest we forget

Many today have forgotten our past, whilst some have even purposefully erased it, hoping that what they did or were responsible for doesn’t catch up with them sooner or later.

What we cannot undo, could however be rewritten to help provide us today with a safer route for our life’s journey into the future. To solve our problems of the future, we must become its solutions of today.

Our lives are made up of very critical moments or what many refer to as life’s sign posts where very huge life changing impacts, affect our perception and sense of meaning towards life itself.

In April of 1996, I personally watched, in one of the most tragic moments in my life, the horrors of war in South Lebanon, the Qana massacre, where hundreds of innocent men, women and children became an unfortunate and tragic collateral of war.

Witnessing it firsthand, the horror and sights of dismembered bodies, the strong smell of iron from burning bodies and sounds of grief, despair and anger for the loss of innocent lives.

Occasional triggers bring back images and vivid memories of that tragic day, describing what man is capable of during war and conflict, where power, lust and greed become more important than ones very own sense of humanity.

Overcoming such flashbacks have never been easy, but they have provided me with a more cautious approach towards life itself

Lead up to the mutiny

Twenty-one years ago today, another very personal signpost flashes prominently – linked to tragedy, conflict, death and greed, all caught up on this particular day.

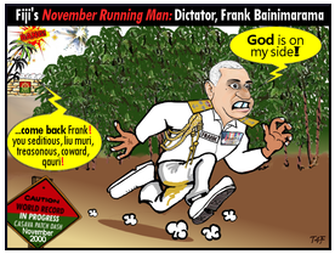

Brought about by selfish aspirations of greedy and power-hungry individuals and opportunists, determined to create disunity and chaos in the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) and force the country into the brink of civil war and total disaster.

I was a young captain – working in our intelligence unit, analysing the implications of the current events as a result of the 2000 coup, the involvement of the CRW unit, their rehabilitation process to reintegrate back into the RFMF and the then political climate.

Months before the 2nd November mutiny, we had already assessed and briefed the RFMF leadership of a highly likely move to remove the current commander, Commodore Bainimarama at the time by rogue elements within the RFMF. We however could not confirm an actual time and day for the mutiny.

Whilst the RFMF loyalists were implementing its plan of re-integrating these rogue elements under a plan named ‘Prodigal Son’, certain disgruntled elements within the RFMF, under constant covert surveillance, were working in a counter plan named ‘Moses’ that included the moving of arms caches and personnel and organising pocket meetings with civilians in what was being assessed as the preconditions building towards the 2nd November mutiny.

This was also followed by the constant approaches from some senior elements, then within the RFMF, to downgrade our assessments that could influence changes with the protective levels of personnel security shadowing the Commander at that time.

The mutineers strike

The unfortunate events of the day began after mid-day, together with a fellow officer; we were working on preparing an intelligence briefing for the Commander, highlighting intelligence indications of a possible palace coup within the RFMF.

The indicators coming from our sources were consistent and increasing daily.

Approximately after midday, gunfire in the direction of the 3FIR complex broke the normalcy of the day. Another sound of gunfire and shouts were a lot closer outside our complex with sounds of boots running along the corridors.

The consistent pattern of controlled gunfire, sound of boots and shouting was immediately recognised as house clearing drills used in operations conducted whilst Fighting in Built Up Areas (FIBUA Ops).

As the synchronised sounds of gunfire, boots and shouting came closer, I shouted in a loud voice, declaring we were two unarmed persons in the office.

The door burst open followed by a pair of focused and determined killer eyes behind the sights and aperture of an automatic weapon.

Sweat was pouring down his face as he ordered us to the floor, followed by the order that we crawl outside onto the corridor leading to the RFMF National Operations Centre (NOC). Our hands are immediately bounded, and we are taken and held as hostages in the NOC.

For the duration of the events that unfolded on this very tragic day, the NOC became a strategic vantage point for me as I listen to the ongoing conversations confidently being discussed as the next order of operations was issued by the hostage takers.

A realisation of great uncertainty and fear settled in as the unfolding plans and intentions of these rogue elements were confidentially discussed openly over telephone calls with the details of bringing in prominent former RFMF individuals and busloads of civilians into the camp to be armed immediately.

Their intent was to create armed groups, that would be sent out later to arrest and apprehend all remaining RFMF loyalist officers, force a change in leadership to the extent of bringing the RFMF and the nation to its knees, to succumb to their selfish and power-hungry desires.

However, from the beginning of that fateful day, the order to eliminate the Commander and RFMF hostages, arm the busloads of civilians and handover control to very prominent ex-RFMF individuals was continuously short lived through the intervening hands of providence.

The situations changed strategically to the favour of the RFMF, as critical threat conditions were not achieved. One by one, each threat condition was systematically mitigated and placed under strict control; the RFMF re-established a firm base to re-gain the initiative and reaffirm control over the threatening situation.

Lessons learned

If there was a great lesson to be learnt by those who wanted to act in defiance, the rogue elements were only trained to hold ground for a short period.

Their role was nev that decisive battle, dow of opportunity about winning but exploit a winthat could provide that opportunity for a more consistent and self-sustaining capability to exploit. Their failure was the thought that they were capable enough to move from a hit-andrun role to a stand, fight and hold ground role.

Time was never on their side; however, it was a critical enabler for the RFMF loyal troops because it provided them with the ability to regenerate its strength and fighting power to a more determined level of capability to retake QEB.

As the hostage takers began to lose the initiative, the plans to re-take QEB by RFMF loyalist troops was executed. Sounds of advancing gunfire and high explosions became more co-ordinated and systematic.

The rogue elements began to disappear. The situation became more complicated as it transitioned into a phase of deep unknown.

Loyalist troops fought and took back QEB inch by inch, clarity of identifying the forces at play and the hostage from its capturers at this point was critical as those sitting on the fence began to jump at the opportunity of being loyalists again.

The officer ordered to execute us, threw his pistol under the bench as the situation and control changed to the hands of loyalist troops.

As the assault commenced with loud explosions and automatic gunfire, the order for us was to look for cover and protect ourselves until the loyalists clearing teams cleared the area. For almost two minutes heavy explosions rocked the camp.

There were seven of us held as hostages in an office adjacent to the NOC. We all huddled at the furthest corner of the office, hoping and praying that the heavy explosions would not be aimed directly into the building we were being held in.

The heavy explosions began to sound very close for some time and then faded further away as the next wave of automatic gunfire approached again in the systematic rhythm familiar to house clearing drills in FIBUA.

As it moved closer, we started shouting declaring our status as hostages, our numbers and being unarmed. Similar sights of soldiers, with killer eyes, ordered everyone down and asked whether we were for or against, frisking and searching us individually for weapons before confirming us as friendlies.

Into the night

The mood in the middle of the night was very complex.

Determining who was standing on which side became very complicated and emotional as the lines of questioning and interrogation became physical.

Emotions were running high as the count of our losses were being realised. Command and control became critical to maintaining a sense of order and stability.

Trust became questionable, as soldiers began to question young leaders of their loyalty.

Rouge elements were being pursued as they abandoned their post and mission after realising how untenable the situation had become.

As the hours passed and the days went by, prominent individuals were singled out and linked to the mutiny; their selfish agendas had caused the lives of individuals on both sides, where families became part of that collateral.

Honouring the fallen

Twenty-one years later, we relive that memory. Today, in honour of those who unfortunately lost their lives in defending the institution. We honour their families for the sacrifices they have had to endure and will continue to endure throughout all their generations.

We will never forget what happened, we will never forget those who lost their lives, we will never forget the families who lost their fathers, sons and grandsons.

We will continue to tell its tale, we will continue to allow this day to shape our institution as we advocate our ethos of being True, Just and Fair in all we do and stand for.

2nd November will always be engraved in our history, it will always be the reason for us to keep aloft our colours and standards ensuring that they never fall again to such selfish and power-hungry agendas.

We will always ensure that the lives we lost were never in vain, but become the raison d’etre of ensuring the defense, security and well-being of Fiji and all Fijians. We will never allow this to happen again. We will never allow such selfish and power-hungry individuals to exploit the RFMF for their personal gains. We will stand for the right of every Fijian regardless of race, ethnicity, colour or creed.

The following is a personal recollection of the events of 2nd November 2000 by the Commander RFMF, Major General Jone Kalouniwai. Source: The Fiji Sun

Lest we forget

Many today have forgotten our past, whilst some have even purposefully erased it, hoping that what they did or were responsible for doesn’t catch up with them sooner or later.

What we cannot undo, could however be rewritten to help provide us today with a safer route for our life’s journey into the future. To solve our problems of the future, we must become its solutions of today.

Our lives are made up of very critical moments or what many refer to as life’s sign posts where very huge life changing impacts, affect our perception and sense of meaning towards life itself.

In April of 1996, I personally watched, in one of the most tragic moments in my life, the horrors of war in South Lebanon, the Qana massacre, where hundreds of innocent men, women and children became an unfortunate and tragic collateral of war.

Witnessing it firsthand, the horror and sights of dismembered bodies, the strong smell of iron from burning bodies and sounds of grief, despair and anger for the loss of innocent lives.

Occasional triggers bring back images and vivid memories of that tragic day, describing what man is capable of during war and conflict, where power, lust and greed become more important than ones very own sense of humanity.

Overcoming such flashbacks have never been easy, but they have provided me with a more cautious approach towards life itself

Lead up to the mutiny

Twenty-one years ago today, another very personal signpost flashes prominently – linked to tragedy, conflict, death and greed, all caught up on this particular day.

Brought about by selfish aspirations of greedy and power-hungry individuals and opportunists, determined to create disunity and chaos in the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) and force the country into the brink of civil war and total disaster.

I was a young captain – working in our intelligence unit, analysing the implications of the current events as a result of the 2000 coup, the involvement of the CRW unit, their rehabilitation process to reintegrate back into the RFMF and the then political climate.

Months before the 2nd November mutiny, we had already assessed and briefed the RFMF leadership of a highly likely move to remove the current commander, Commodore Bainimarama at the time by rogue elements within the RFMF. We however could not confirm an actual time and day for the mutiny.

Whilst the RFMF loyalists were implementing its plan of re-integrating these rogue elements under a plan named ‘Prodigal Son’, certain disgruntled elements within the RFMF, under constant covert surveillance, were working in a counter plan named ‘Moses’ that included the moving of arms caches and personnel and organising pocket meetings with civilians in what was being assessed as the preconditions building towards the 2nd November mutiny.

This was also followed by the constant approaches from some senior elements, then within the RFMF, to downgrade our assessments that could influence changes with the protective levels of personnel security shadowing the Commander at that time.

The mutineers strike

The unfortunate events of the day began after mid-day, together with a fellow officer; we were working on preparing an intelligence briefing for the Commander, highlighting intelligence indications of a possible palace coup within the RFMF.

The indicators coming from our sources were consistent and increasing daily.

Approximately after midday, gunfire in the direction of the 3FIR complex broke the normalcy of the day. Another sound of gunfire and shouts were a lot closer outside our complex with sounds of boots running along the corridors.

The consistent pattern of controlled gunfire, sound of boots and shouting was immediately recognised as house clearing drills used in operations conducted whilst Fighting in Built Up Areas (FIBUA Ops).

As the synchronised sounds of gunfire, boots and shouting came closer, I shouted in a loud voice, declaring we were two unarmed persons in the office.

The door burst open followed by a pair of focused and determined killer eyes behind the sights and aperture of an automatic weapon.

Sweat was pouring down his face as he ordered us to the floor, followed by the order that we crawl outside onto the corridor leading to the RFMF National Operations Centre (NOC). Our hands are immediately bounded, and we are taken and held as hostages in the NOC.

For the duration of the events that unfolded on this very tragic day, the NOC became a strategic vantage point for me as I listen to the ongoing conversations confidently being discussed as the next order of operations was issued by the hostage takers.

A realisation of great uncertainty and fear settled in as the unfolding plans and intentions of these rogue elements were confidentially discussed openly over telephone calls with the details of bringing in prominent former RFMF individuals and busloads of civilians into the camp to be armed immediately.

Their intent was to create armed groups, that would be sent out later to arrest and apprehend all remaining RFMF loyalist officers, force a change in leadership to the extent of bringing the RFMF and the nation to its knees, to succumb to their selfish and power-hungry desires.

However, from the beginning of that fateful day, the order to eliminate the Commander and RFMF hostages, arm the busloads of civilians and handover control to very prominent ex-RFMF individuals was continuously short lived through the intervening hands of providence.

The situations changed strategically to the favour of the RFMF, as critical threat conditions were not achieved. One by one, each threat condition was systematically mitigated and placed under strict control; the RFMF re-established a firm base to re-gain the initiative and reaffirm control over the threatening situation.

Lessons learned

If there was a great lesson to be learnt by those who wanted to act in defiance, the rogue elements were only trained to hold ground for a short period.

Their role was nev that decisive battle, dow of opportunity about winning but exploit a winthat could provide that opportunity for a more consistent and self-sustaining capability to exploit. Their failure was the thought that they were capable enough to move from a hit-andrun role to a stand, fight and hold ground role.

Time was never on their side; however, it was a critical enabler for the RFMF loyal troops because it provided them with the ability to regenerate its strength and fighting power to a more determined level of capability to retake QEB.

As the hostage takers began to lose the initiative, the plans to re-take QEB by RFMF loyalist troops was executed. Sounds of advancing gunfire and high explosions became more co-ordinated and systematic.

The rogue elements began to disappear. The situation became more complicated as it transitioned into a phase of deep unknown.

Loyalist troops fought and took back QEB inch by inch, clarity of identifying the forces at play and the hostage from its capturers at this point was critical as those sitting on the fence began to jump at the opportunity of being loyalists again.

The officer ordered to execute us, threw his pistol under the bench as the situation and control changed to the hands of loyalist troops.

As the assault commenced with loud explosions and automatic gunfire, the order for us was to look for cover and protect ourselves until the loyalists clearing teams cleared the area. For almost two minutes heavy explosions rocked the camp.

There were seven of us held as hostages in an office adjacent to the NOC. We all huddled at the furthest corner of the office, hoping and praying that the heavy explosions would not be aimed directly into the building we were being held in.

The heavy explosions began to sound very close for some time and then faded further away as the next wave of automatic gunfire approached again in the systematic rhythm familiar to house clearing drills in FIBUA.

As it moved closer, we started shouting declaring our status as hostages, our numbers and being unarmed. Similar sights of soldiers, with killer eyes, ordered everyone down and asked whether we were for or against, frisking and searching us individually for weapons before confirming us as friendlies.

Into the night

The mood in the middle of the night was very complex.

Determining who was standing on which side became very complicated and emotional as the lines of questioning and interrogation became physical.

Emotions were running high as the count of our losses were being realised. Command and control became critical to maintaining a sense of order and stability.

Trust became questionable, as soldiers began to question young leaders of their loyalty.

Rouge elements were being pursued as they abandoned their post and mission after realising how untenable the situation had become.

As the hours passed and the days went by, prominent individuals were singled out and linked to the mutiny; their selfish agendas had caused the lives of individuals on both sides, where families became part of that collateral.

Honouring the fallen

Twenty-one years later, we relive that memory. Today, in honour of those who unfortunately lost their lives in defending the institution. We honour their families for the sacrifices they have had to endure and will continue to endure throughout all their generations.

We will never forget what happened, we will never forget those who lost their lives, we will never forget the families who lost their fathers, sons and grandsons.

We will continue to tell its tale, we will continue to allow this day to shape our institution as we advocate our ethos of being True, Just and Fair in all we do and stand for.

2nd November will always be engraved in our history, it will always be the reason for us to keep aloft our colours and standards ensuring that they never fall again to such selfish and power-hungry agendas.

We will always ensure that the lives we lost were never in vain, but become the raison d’etre of ensuring the defense, security and well-being of Fiji and all Fijians. We will never allow this to happen again. We will never allow such selfish and power-hungry individuals to exploit the RFMF for their personal gains. We will stand for the right of every Fijian regardless of race, ethnicity, colour or creed.

The appearance of former Commander, General Sitiveni Rabuka, at QEB on that day created mixed feelings. The Fiji Times on November 3, 2000, talks of how he (Rabuka) was approached to mediate. Yet, no names of who approached him is mentioned. There is another train of thought in QEB that he was there “in support” of the mutiny. We will never know the truth. But 21 years on, we must ask the question why a former Commander of the RFMF turned up at QEB without an invite from the current Commander at the time! Former military commanders the world over is revered and only turn up at Garrisons on the invite of its Commander. That is the general custom and military tradition. The fact is, Commodore Bainimarama had never issued an invite to General Rabuka to be in QEB on the day of the mutiny!

A DAY that will go down in the history of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces as its darkest hour and to some extent its most enlightening too in terms of the undercurrent sweeping through a divided military that needed to a re-assure itself of its duty to the nation and the people of Fiji.

While there will be stories told of the heroism of some in the face of adversity and the cowardice of a few in the moments of chaos, we will share some insights of how the mutiny of November 2, 2000 was in no way an isolated incident nor was it a sudden or quickly hatched plan in a matter of minutes and hours.

The plan to takeover Queen Elizabeth Barracks, its armories’, its Operational cell along with the killing or incapacitation of the Commander RFMF was deliberate and methodical in its planning. Thankfully, it lacked “precision” and “accuracy”.

To talk about the mutiny of November 2, 2000, we must look at the events leading up to it. There will be differences in opinion and story depending on who you speak with, it doesn’t take away the fact that the mutiny happened.

And it was a result of the prevailing political situation in the country at the time.

Attempting to relook at the incident from a purely military perspective can be daunting.

There will be grey areas where the lines become blurred due to the intertwining of events and those involved.

Nonetheless, the story must be told, and the events re-lived on paper to remind us of how a few very selfish, ego- centric and evil men almost succeeded in bringing our nation to its knees.

THE CONSTITUTIONS

After the two coups by Sitiveni Rabuka in 1987, the constitution in place from 1990 was seen as protecting the interests of the indigenous Fijians (iTaukei), and to ensure a consistency in the practice of “protection”, Fijian leaders were also to be governing.

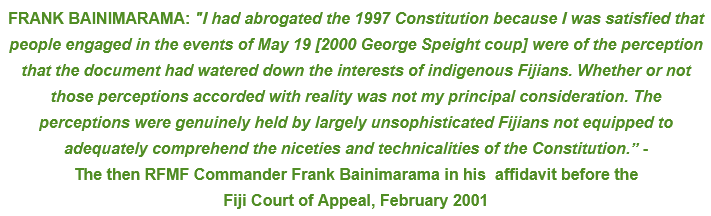

While the changes in the 1997 Constitution were brought about by the recognition of the iTaukei leaders to have some form of multiracial governance system set in place to allow for acceptance and re-engagement in the international diplomatic arena and to ensure economic recovery, there remained a segment of the indigenous Fijian society that saw the changes in the 1997 Constitution as a betrayal of their belief in “iTaukei supremacy”.

The elections of May 1999 under the 1997 Constitution gave birth to Fiji’s first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister, Mahendra Chaudhry.

His Fiji Labour Party (FLP) won decisively by winning 37 of the 71 seats. Whatever reasons given for the demise of Rabuka’s Soqosoqo Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT) Party in the 1999 elections, one thing is clear, the iTaukei voters had been split along racial lines and by seeing through the evolution of Sitiveni Rabuka into a “multiracial politician”.

Perhaps too much had been “given up” from the 1990 Constitution to allow for the 1997 “multiracial” Constitution.

The takeover of the Chaudhry Government by George Speight and members of the Counter Revolutionary Warfare (CRW) squadron on May 19, 2000, sparked a lot of interest within the RFMF establishment.

While there were elements of the RFMF who supported the takeover, the Commander RFMF at the time, Commodore Voreqe Bainimarama was adamant that the RFMF would not be dragged into supporting the actions of a few renegades from QEB.

Once the CRW renegades, led by their Officer Commanding Major Ligairi, were convinced that the RFMF would not support their actions, they then sat in for an attrition hostage situation.

As the hostage situation turned from hours, into days and then to weeks, there were reports of looting, cattle theft, and lawlessness in communities around Fiji.

This was especially rife in areas where Indo Fijians were living, and the criminal opportunists exploited their fear to allow for maximum gain.

To add to the uncertainty, two soldiers were wounded, and the life of a police officer was taken, the 1997 Constitution was abrogated, and the President, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, stood down.

The CRW men were playing on the general thinking that Fijians would never act to kill one another.

This allowed them access to media, visitors, well-wishers and movement in and out of the Veiuto Parliament complex while their hostages were held within the confines of the complex.

The environment of paranoia within the RFMF also grew. Senior officers who made decisions regarding the sustenance of the renegade CRW group in Parliament were seen to be actively working against the directive and wishes of the Commander of the RFMF.

It was an environment of doubt and continuous question. Every command from those in the higher echelons of the RFMF had to be dissected and re-examined to ensure that it was in line with the intent of the RFMF Commander.

Opportunists in the higher echelons of the RFMF were also becoming evident. Intentional undermining of the intent and decisions of the RFMF Commander became obvious in some instances.

MUTINY PLANNED

The signing of the Muanikau Accord brought the hostage situation to an end and the renegade CRW group along with their adopted leader, George Speight, and supporters moved to Kalabu Fijian School outside Suva.

To back up removal of the RFMF leadership, the CRW squadron needed to have civilians supporting them.

The Qaranivalu assured the CRW members of the support of the vanua. Information from the meetings suggested that the Qaranivalu allegedly had talks with a former RFMF Commander, who would be supporting the change of leadership.

The appearance of former Commander, General Sitiveni Rabuka, at QEB on that day created mixed feelings.

The Fiji Times on November 3, 2000, talks of how he (Rabuka) was approached to mediate.

Yet, no names of who approached him is mentioned.

There is another train of thought in QEB that he was there “in support” of the mutiny.

We will never know the truth. But 21 years on, we must ask the question why a former Commander of the RFMF turned up at QEB without an invite from the current Commander at the time!

Former military commanders the world over is revered and only turn up at Garrisons on the invite of its Commander.

That is the general custom and military tradition. The fact is, Commodore Bainimarama had never issued an invite to General Rabuka to be in QEB on the day of the mutiny!

The original date for the mutiny had been set for Diwali of 2000.

Due to a compromise in that date, it was decided to leave the date open and work on the situation as it evolved.

It was the height of chaos in a country which prided itself in its hospitality, friendliness, and the way the world should be!

The decision by the RFMF Commander not to support the illegal actions of the renegade CRW squadron group during the hostage situation in Parliament in 2000 posed a major setback in the overall scheme of things for George Speight and his group.

With no sustainable support from QEB the CRW group in Parliament were on their own with a group of civilians who were largely naïve to the intentions of the group.

The Commander also made the decision to disband the unit once everything had settled down.

Following the move of the group to Kalabu from Parliament, the RFMF and Fiji Police Force stormed the Kalabu school compound and detained all those in the premises.

This included renegade members of the CRW squadron.

The night before, George Speight was apprehended and moved to Nukulau Island where a temporary prison had been set up.

Following the clearance of Kalabu and the detainment of George Speight and his group on Nukulau, the RFMF turned to the North and recaptured Sukanaivalu Barracks in Labasa and moved down to Savusavu for more security and stability operations.

After Vanua Levu, the RFMF deployed troops to Naitasiri to retake the Monasavu Dam. Naitasiri had openly declared their support for the takeover through Ratu Inoke Takiveikata, the Turaga na Qaranivalu.

With the military moving from one operation to another, in an attempt to ensure that there was no widespread consistent armed insurgency, there were already attempts at QEB to have members of the CRW squadron rehabilitated and reintegrated into the military.

While the members of the military who remained loyal to the RFMF Commander went about their daily duties, plans were also being hatched albeit in the form of expression of disappointment within a group to plan the mutiny.

Meetings held at Ragg Avenue in Suva and later in Nausori echoed sentiments of a dislike in the way the military had handled the Kalabu, Sukanaivalu, Monasavu and other incidents around Fiji.

The iron fist that had descended itself in the form of the military teams that crushed any isolated incidents around the country were perhaps an outpouring of the frustration of the soldiers who had been ridiculed, and many a time, verbally abused by the supporters of George Speight during the 56 days of captivity in Parliament.

The meetings confirmed the need for a change of leadership in the RFMF.

While there will be stories told of the heroism of some in the face of adversity and the cowardice of a few in the moments of chaos, we will share some insights of how the mutiny of November 2, 2000 was in no way an isolated incident nor was it a sudden or quickly hatched plan in a matter of minutes and hours.

The plan to takeover Queen Elizabeth Barracks, its armories’, its Operational cell along with the killing or incapacitation of the Commander RFMF was deliberate and methodical in its planning. Thankfully, it lacked “precision” and “accuracy”.

To talk about the mutiny of November 2, 2000, we must look at the events leading up to it. There will be differences in opinion and story depending on who you speak with, it doesn’t take away the fact that the mutiny happened.

And it was a result of the prevailing political situation in the country at the time.

Attempting to relook at the incident from a purely military perspective can be daunting.

There will be grey areas where the lines become blurred due to the intertwining of events and those involved.

Nonetheless, the story must be told, and the events re-lived on paper to remind us of how a few very selfish, ego- centric and evil men almost succeeded in bringing our nation to its knees.

THE CONSTITUTIONS

After the two coups by Sitiveni Rabuka in 1987, the constitution in place from 1990 was seen as protecting the interests of the indigenous Fijians (iTaukei), and to ensure a consistency in the practice of “protection”, Fijian leaders were also to be governing.

While the changes in the 1997 Constitution were brought about by the recognition of the iTaukei leaders to have some form of multiracial governance system set in place to allow for acceptance and re-engagement in the international diplomatic arena and to ensure economic recovery, there remained a segment of the indigenous Fijian society that saw the changes in the 1997 Constitution as a betrayal of their belief in “iTaukei supremacy”.

The elections of May 1999 under the 1997 Constitution gave birth to Fiji’s first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister, Mahendra Chaudhry.

His Fiji Labour Party (FLP) won decisively by winning 37 of the 71 seats. Whatever reasons given for the demise of Rabuka’s Soqosoqo Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT) Party in the 1999 elections, one thing is clear, the iTaukei voters had been split along racial lines and by seeing through the evolution of Sitiveni Rabuka into a “multiracial politician”.

Perhaps too much had been “given up” from the 1990 Constitution to allow for the 1997 “multiracial” Constitution.

The takeover of the Chaudhry Government by George Speight and members of the Counter Revolutionary Warfare (CRW) squadron on May 19, 2000, sparked a lot of interest within the RFMF establishment.

While there were elements of the RFMF who supported the takeover, the Commander RFMF at the time, Commodore Voreqe Bainimarama was adamant that the RFMF would not be dragged into supporting the actions of a few renegades from QEB.

Once the CRW renegades, led by their Officer Commanding Major Ligairi, were convinced that the RFMF would not support their actions, they then sat in for an attrition hostage situation.

As the hostage situation turned from hours, into days and then to weeks, there were reports of looting, cattle theft, and lawlessness in communities around Fiji.

This was especially rife in areas where Indo Fijians were living, and the criminal opportunists exploited their fear to allow for maximum gain.

To add to the uncertainty, two soldiers were wounded, and the life of a police officer was taken, the 1997 Constitution was abrogated, and the President, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, stood down.

The CRW men were playing on the general thinking that Fijians would never act to kill one another.

This allowed them access to media, visitors, well-wishers and movement in and out of the Veiuto Parliament complex while their hostages were held within the confines of the complex.

The environment of paranoia within the RFMF also grew. Senior officers who made decisions regarding the sustenance of the renegade CRW group in Parliament were seen to be actively working against the directive and wishes of the Commander of the RFMF.

It was an environment of doubt and continuous question. Every command from those in the higher echelons of the RFMF had to be dissected and re-examined to ensure that it was in line with the intent of the RFMF Commander.

Opportunists in the higher echelons of the RFMF were also becoming evident. Intentional undermining of the intent and decisions of the RFMF Commander became obvious in some instances.

MUTINY PLANNED

The signing of the Muanikau Accord brought the hostage situation to an end and the renegade CRW group along with their adopted leader, George Speight, and supporters moved to Kalabu Fijian School outside Suva.

To back up removal of the RFMF leadership, the CRW squadron needed to have civilians supporting them.

The Qaranivalu assured the CRW members of the support of the vanua. Information from the meetings suggested that the Qaranivalu allegedly had talks with a former RFMF Commander, who would be supporting the change of leadership.

The appearance of former Commander, General Sitiveni Rabuka, at QEB on that day created mixed feelings.

The Fiji Times on November 3, 2000, talks of how he (Rabuka) was approached to mediate.

Yet, no names of who approached him is mentioned.

There is another train of thought in QEB that he was there “in support” of the mutiny.

We will never know the truth. But 21 years on, we must ask the question why a former Commander of the RFMF turned up at QEB without an invite from the current Commander at the time!

Former military commanders the world over is revered and only turn up at Garrisons on the invite of its Commander.

That is the general custom and military tradition. The fact is, Commodore Bainimarama had never issued an invite to General Rabuka to be in QEB on the day of the mutiny!

The original date for the mutiny had been set for Diwali of 2000.

Due to a compromise in that date, it was decided to leave the date open and work on the situation as it evolved.

It was the height of chaos in a country which prided itself in its hospitality, friendliness, and the way the world should be!

The decision by the RFMF Commander not to support the illegal actions of the renegade CRW squadron group during the hostage situation in Parliament in 2000 posed a major setback in the overall scheme of things for George Speight and his group.

With no sustainable support from QEB the CRW group in Parliament were on their own with a group of civilians who were largely naïve to the intentions of the group.

The Commander also made the decision to disband the unit once everything had settled down.

Following the move of the group to Kalabu from Parliament, the RFMF and Fiji Police Force stormed the Kalabu school compound and detained all those in the premises.

This included renegade members of the CRW squadron.

The night before, George Speight was apprehended and moved to Nukulau Island where a temporary prison had been set up.

Following the clearance of Kalabu and the detainment of George Speight and his group on Nukulau, the RFMF turned to the North and recaptured Sukanaivalu Barracks in Labasa and moved down to Savusavu for more security and stability operations.

After Vanua Levu, the RFMF deployed troops to Naitasiri to retake the Monasavu Dam. Naitasiri had openly declared their support for the takeover through Ratu Inoke Takiveikata, the Turaga na Qaranivalu.

With the military moving from one operation to another, in an attempt to ensure that there was no widespread consistent armed insurgency, there were already attempts at QEB to have members of the CRW squadron rehabilitated and reintegrated into the military.

While the members of the military who remained loyal to the RFMF Commander went about their daily duties, plans were also being hatched albeit in the form of expression of disappointment within a group to plan the mutiny.

Meetings held at Ragg Avenue in Suva and later in Nausori echoed sentiments of a dislike in the way the military had handled the Kalabu, Sukanaivalu, Monasavu and other incidents around Fiji.

The iron fist that had descended itself in the form of the military teams that crushed any isolated incidents around the country were perhaps an outpouring of the frustration of the soldiers who had been ridiculed, and many a time, verbally abused by the supporters of George Speight during the 56 days of captivity in Parliament.

The meetings confirmed the need for a change of leadership in the RFMF.