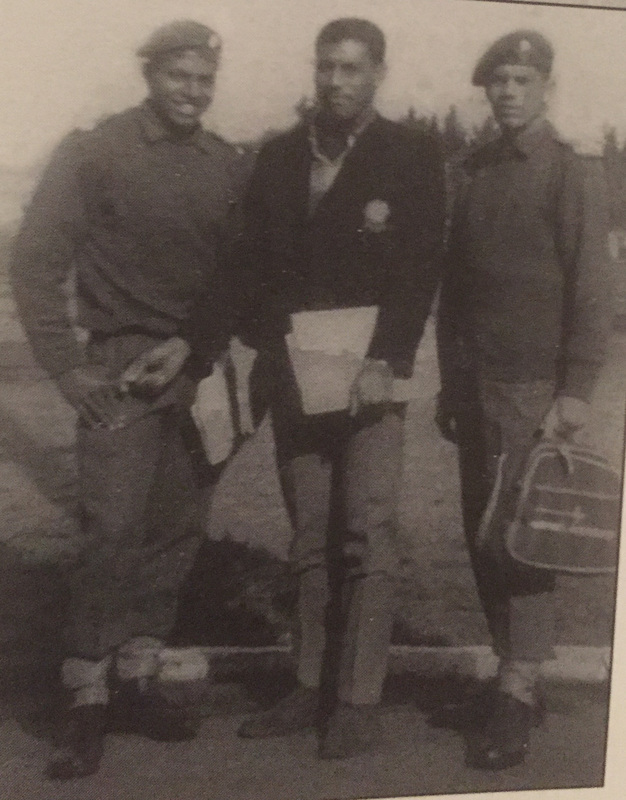

The then Chief of Staff Jim Sanday had stood before Rabuka shortly after the 14 May 1987 coup and had ordered him (Rabuka) to hand to him (Sanday) his (Rabuka's) 9mm Browning pistol and to empty the NINE bullets if he wanted to enter Government House to speak to the Governor-General Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau...Rabuka sheepishly complied and in Sanday's presence, unloaded the bullets.

In retaliation Rabuka denied Sanday Fiji Republic Medal because he [Sanday] did NOT support the 1987 coups - Rabuka promoted himself (told Ratu Penaia) to promote him as Major-General of RFMF

But we can disclose for the first time what has not been spoken about or revealed by Rabuka in his autobiography No Other Way and the sanctioned biography Rabuka of Fiji.

As we know, Rabuka had rocked up to Government House on 14 May 1987 after the coup at 10.00am. A day before, he had arranged for his immediate superior Lt-Colonel Sanday to represent him for a briefing meeting on national security with Ratu Penaia. In fact, Rabuka had set up the meeting through Ratu Penaia's ADC Lesi Korovavala, a third class ambitious and unimpressive young officer. It was Korovavala who had rung Sanday's wife on 13 May to arrange the meeting.

A Fijileaks investigation reveal that when Rabuka turned up to Government House, Sanday went out to meet him before he [Rabuka] went in to see Ratu Penaia. Sanday saw that he (Rabuka) had a 9mm Browning pistol in his pocket. He had arrived with his escort of soldiers, some of whom were members of the Army Rugby 1st XV. Sanday was President of the Army Rugby Club and they turned away out of shame when Sanday went out to meet them.

As his life time Army buddy and as his Commanding Officer at the time, and, in the best traditions of a professional military officer that Sanday was, he invited the coupist Rabuka to remove the pistol from his coat pocket and unload it as there was no need for him to take a loaded pistol into discussions with the Queens representative in Fiji.

Rabuka sheepishly complied and in Sanday's presence unloaded nine (x9) 9mm rounds from the magazine of the 9mm Browning pistol which he carried with him to Government House.

Sanday realized there and then, that his dear Army buddy that he had joined the Army together with in January 1968, and in whom Sanday had given him his (Sanday's) complete trust, had a darker side to his character that was prepared to shaft his closest buddies in his quest for his self-serving quest for national leadership.

The coupster never forgave Sanday. When Rabuka introduced the Fiji Republic Medal, Sanday was told by senior officers loyal to Rabuka that he was not entitled to it because he did not support the coup. So Sanday told them to shove that medal up where the sun don't shine. And, Sanday has never worn that medal since.

Fijileaks: In his 4 the Record interview with FBC Rabuka refused to disclose the names of those behind the 1987 coups. Our founding editor-in-chief VICTOR LAL has identified many of the key figures in his book Fiji: Coups in Paradise - Race, Politics and Military Intervention. We re-publish an excerpt that was published by the pro-democracy blog C4/5 in May 2010 under the title Who Was Who in the 1987 Coups?

A former Minister for Fijian Affairs and Deputy Prime Minister in Ratu Mara’s Alliance government, on 12 February 1983, Ratu Penaia had been officially sworn in by the Chief Justice, Sir Timoci Tuivaqa, as Fiji’s third Governor-General, the second high chief to such a position.

In his acceptance speech Ratu Penaia stressed that ‘Fiji’s link with the British Crown is a long and treasured one, and I feel deeply honoured to have been chosen to perpetuate that link into the future.'

He declared that he would practice political neutrality in discharging the heavy responsibility laid upon him...On 14 May 1987, however, in his capacity as the Governor-General Ratu Penaia suddenly found himself in an awkward position trying to reconcile three conflicting forces: loyalty to the Queen; protection of Fiji Indian interests; and his duty as a chief to safeguard the interests of his Fijian population.

Ratu Penaia’s initial reaction to the coup was one of ‘shock’ and surprise, until Rabuka called upon him at Government House to explain his actions. The following exchanges between Ratu Penaia and Rabuka shortly afterwards is worth recalling here as we examine the Governor-General’s role in the whole crisis.

According to Rabuka, the conversation began in English:

Rabuka: Sir, I have just taken over the Government. I have detained all Dr Bavadra’s team. They have been taken up to camp, where they will be detained until we find suitable accommodation for them.

Ratu Penaia: What have you done?

R: I have suspended the Constitution, or abrogated the Constitution, and that means, Sir, that your appointment as Governor-General now ceases to exist.

RP: You mean that I have no job?

R: (Now speaking in Fijian): Yes, Sir, but I would ask that you stay here with full pay and all your privileges and honours that go with your office, until we ask you to come back as President.

RP: Couldn’t you have given them (the Coalition) time to carry out their policies?

R: Sir, it would be very dangerous to let them run the Government for a few more months?

RP: Have you thought about what are you going to do next? What about the Tui Nayau (Ratu Mara)?

Rabuka disclosed that his next steps were: the formation of a Council of Ministers comprising former Alliance ministers to run an interim government, prior to holding another election; and that he wanted Ratu Mara on the Council because he would be a ‘trump card’, a ‘must’ as Minister for Foreign Affairs. Ratu Penaia was sympathetic to Rabuka’s essential aims, but, according to Rabuka, told him what he had done was unconstitutional, and he (Ratu Penaia) would go along with it.

But in light of the Governor-General’s role later it remains possible that he endorsed Rabuka’s overall aims if not the causes. That the Governor-Genereal had initially accepted his dismissal in another example of apparent indifference to the coup. Had it not been for the intervention of the Chief Justice, Sir Timoci Tuivaqa, events at the time might have taken a different turn. Sir Timoci has disclosed that he was in his chamber when his Chief Registrar notified him of the coup. He awaited for a call from the Governor-General, which never came. Sir Timoci eventually telephoned the Governor-General, and said: ‘Sir, there’s a political crisis on our hands. What are we doing about it?’

According to Victor Lal, who has quoted the Chief Justice’s conversation extenso, it was after that phone call that spurred Ratu Penaia into action.

Lal continues: ‘In a recorded radio message broadcast on a private Suva radio system FM96, before it was seized by the military, Ratu Penaia expressed his deep shock and regret at the usurpation of power by the military. While deploring the coup he called on the mutineering troops to end their rebellion, declared a state of emergency, and said that he personally, was taking charge of the government in the absence of his Cabinet. Unabased, Rabuka announced shortly afterwards that he had appointed his own Council of Ministers, with prominent among them, Ratu Mara and many of his former Alliance ministers. The ex-Minister of education, Ratu Mara and many of his former Finance Minister, Peter Stinson, in fact, sat on either side of Rabuka when he gave his press conference declaring that he was firmly in control.’

‘The Governor-General, to whom Rabuka had disclosed his post-coup plans, surprisingly, was allowed to remain at Government House, half a mile from Government Buildings in Suva and it was from there that he would persistently assert that he was the sole repository of legal authority in the islands, although he wavered as Rabuka, fully supported by the Great Council of Chiefs, moved gradually to fulfil the objectives of his coup. Moreover, Rabuka’s apparent reluctance to act against the Governor-General, his own paramount chief, and latter’s ‘secret’ swearing in of Rabuka’s Council of Ministers on 17 May, naturally began to raise doubts about Ratu Penaia’s integrity.’

Victor Lal has written in detail the activities and controversial decisions of Ratu Penaia leading to his resignation on 15 October 1987 as Governor-General and Queen’s representative on Fiji Islands. The role Ratu Penaia, states Lal, emerges as the most complex and contentious issue during the 1987 coups. The Governor-General had three possible courses of action:

(1) he could have used the prestige of high office to lead a fight for the restoration of democracy and of the ousted government;

(2) he could have acted within the conventions of British constitutional monarchy, finding therein guidance for his actions; or

(3) as he, in fact, did confirm to political pressures, precepts and expectations of party and race, use his position to contain excesses of military rule without disavowing the coups’ aims.

According to Lal: ‘It does seem that the Governor-General was aware of the imminence of Rabuka’s first coup. As a former Deputy Prime Minister he was also aware that Fijian rights were fully protected in the 1970 Constitution, and yet he remained silent on the issue. Instead, he threw in his lot with the Great Council of Chiefs and Rabuka to reduce Indians to ‘second-class’ citizens. Most importantly, his repeated claims that he was the sole legitimate authority on the islands may have been the factor that prevented the Queen (and possibly, too many others countries) from acting firmly and promptly against Rabuka. Above all, could the Governor-General have presented the coup?

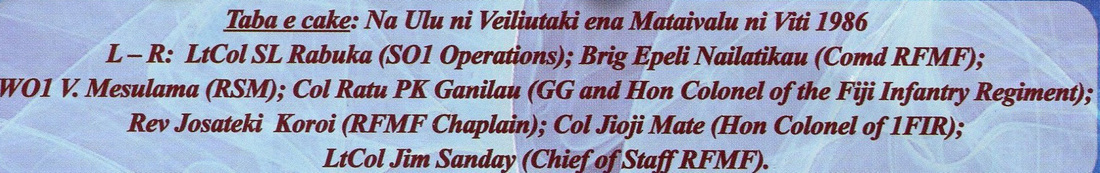

‘The first major sign of Fijian revolt against the Bavadra government took the form of street demonstrations on 23 April 1987. Afterwards, the anti-Bavadra demonstrators handed a petition to the Governor-General in which they declared a vote of no confidence in the NFP/FLP government. The deposed commander of the army, Brigadier Nailatikau, has disclosed that a day before the demonstrations he called together available officers and told them that since the Taukei march was to go ahead, they must perform their duty ‘if things got out of hand and were called in’. Earlier, Bavadra, Ratu Penaia and Nailatikau had held a crisis security meeting, as most of the demonstrators were Fijians. As pointed out in the last chapter, the demonstration was noisy but ended peacefully.

‘What did the Governor-General know about the coup? When did he know? Firstly, it could be argued that although the Governor-General had constitutional authority, he would be powerless to prevent a coup taking place or to effectively oppose one when it happened. If, however, he had prior knowledge of the imminence of a coup he could at least have alerted the government, or the commander of the army – unless the Governor-General himself was party to the plot. What is not known is whether that he had alerted the then army commander, Brigadier Nailatikau, before he (Nailatikau) left Australia in April, shortly after the street demonstrations. The then Prime Minister, Bavadra, was definitely not warned of a possible military coup against his government. In November 1987 Rabuka disclosed that he had warned the Governor-General that if he ‘did not stage a political coup, I would stage a military coup’.

According to Rabuka: ‘The Taukei Movement emerged - with all its plans for violence, demonstrations and arson. It was at that point that I went to the Governor-General, Ratu Penaia, and asked him if there was something we could do. This particularly after the Taukei had submitted their petition to him expressing displeasure at an Indian-dominated government and urging him to intervene and seek an immediate review of the Constitution. I told him that if he did not stage a political coup, I would stage a military coup, I then left.’

Clearly, then, Victor Lal argues, the Governor-General was aware that Rabuka might launch a military. ‘Yet, as the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, it seems that he neither made any move to alert Rabuka’s immediate superiors nor did he dissuade Brigadier Nailatikau from leaving the country. Brigadier Nailatikau claims that he knew nothing of the 14 May coup, but if this was so why did the Governor-General not inform Brigadier Nailatikau so that he could keep Rabuka and other possible coup plotters under surveillance?

Or was it simply a lapse of memory on the Governor-General’s part? If we are to believe Rabuka, or Brigadier Nailatikau, the Governor-General knew of a possible coup, if he was not actually a co-conspirator.

In sum, both the Governor-General and Brigadier Nailatikau’s explanations need further qualifications, and the two questions regarding what the Governor-General knew about the first coup, and when he knew it, remain unanswered.’

And what of the role of another prominent figure – Ratu Mara?

C4/5 Editor: To be continued