Fiji Leaks analysis shows that since the Tappoo Group entered the fuel market in September 2013, the government-enforced fuel retail margin on diesel has miraculously jumped more than 50 percent and more than 60 percent for unleaded after years of flat-lining. But too late to save the 400 low-skilled jobs of the petrol station attendants forced out of work in October 2010, when Khaiyum was happy to ignore fuel retailers’ complaints the margins his Commerce Commission were setting were too low

Would Carpenters (and even BP Oil) have sold out to a regime-friendly company like Tappoo Group and ended more than a century of fuel supply to the Fiji consumer, if they had known the fuel margins would rise so significantly over the short term?

In the driver's seat of corruption,

In the driver's seat of corruption,emitting burnt fuel stench from his corrupt deals

ASTUTE readers of the regime’s faithful newspaper The Fiji Sun may have been left wondering why Aiyaz Khaiyum, the Minister of Finance, had shown a sudden spasm of charity towards fuel distributors, after almost six years of neglect. ‘The fuel retailers’ margins have been fairly low … and now the margin will go up by about one to four percent,’ Aiyaz Khaiyum told the Fiji Sun the Saturday before Christmas.

The sale of petroleum products in Fiji is one of a number of areas not set by conventional free market forces of supply, demand and competition. Fuel retail prices are directly set by the Commerce Commission (which took over the price control powers from the now-disbanded Prices and Income Board when Khaiyum, as the state’s chief law officer, drafted the Commerce Commission Decree 2010, and then folded the Commerce Commission under his responsibility as Attorney-General and Minister of Justice, Ant-Corruption, Public Enterprises, Industry, Tourism, Trade and Communications).

A look at the Commerce Commission website is rather surprising. For an organisation with such a critical role in Fiji business, no commissioners are listed (there must be a minimum of 4 and maximum of 6 and it is in the commissioner’s executive hands that the power lies) and a search of the Fiji government portal shows no recent appointments. The chairman has not been formally replaced since Khaiyum stooge Dr Mahendra Reddy quit to head into politics and elected office. The acting chairman – the Pakistani-born pharmaceutical manager Firoz Ahmad Ghazali – has been holding the fort since July 2014.

As with the functioning of the PIB, some of the workings of the Commerce Commission remain the same. In term of fuel orders, these set the VAT-inclusive price at which the variety of fuel types retailed to the public can be sold. The fuel types covered under the orders are unleaded motor spirit, diesel or gasoil, the premix used in outboard engines, and kerosene. Different prices are set according to the geographic areas of the country.

Like the PIB, the Commerce Commission also determines the wholesale price at which the fuel stations buy-in the products they sell at their forecourts. By setting both the retail and wholesale prices (and determining the rate of VAT), the Commerce Commission also – in effect - sets the margin or profit on every litre sold by the fuel retailers. And it’s a big cash business: The Fiji Fuel Retailers Association has estimated the market to be worth $550m annually, driven by an average of 30,000 visits per day to any of the 70-plus fuel stations covered by its membership.

Since its current inception the Commerce Commission has had mixed results. It was largely responsible for what deregulation has occurred in the local telecommunications market but anybody who uses the internet in Fiji or the so-called 3G and 4G services will tell you the telecom companies continue to run rings around the Commerce Commission. The Commission has involved itself in many bizarre areas of micro-management – ruling on the prices to be paid by yachties at the Copra Shed Marina in Savusavu for instance– but ignoring other more legitimate consumer issues, for instance the Consumer Council’s campaign to stimulate more competition between the country’s two LPG providers. Businesses regulated have accused it of wielding too much power, being too unaccountable and trying to squeeze down retail prices for political benefit irrespective of what that does to margins and employers.

As Hot Bread Kitchen owner Mere Samisoni explained to the Fiji Times when her shops were facing criticism for the scarcity of white longloaf and milk sandwich loaves (both sold at Commerce Commission-controlled pricing that had not changed in four years):

‘This is basic microeconomics, and is the same phenomenon responsible for the dwindling stock level of certain basic commodities in supermarkets and corner stores and for the fall in service levels at supermarkets and petrol bowsers. It is the same reason why nobody in the whole world runs a business whose core business is giving away iPhones for $20. Sure there would be plenty of customer demand. But who could supply any kind of volume at that price?’

That the 2010 Commerce Commission would change from simply doing the work of the Prices and Income Board to become the personal play-thing and score-settling tool of the vengeful Khaiyum was made clear in the text of the decree itself. Or as respected law firm Munro Leys headlined a briefing on the 2010 decree: ‘Mostly the same, more confusing, less to challenge’ Munro Leys had two particular concerns. One was the general sloppiness that many observers have noted is typical of Khaiyum decrees. In this instance he was acting both as Attorney-General and the Minister heading the Commerce Commission he was legislating to create.

As Munro Leys wrote of the decree revealed for the first time on September 24 2010, ‘It is concerning that a Decree which has apparently been in force since 1 July is only made public 11 weeks later, without advance notice. One advantage of first consulting stakeholders is that at least someone proof-reads your work. The Decree demonstrates the dangers of “cut-and-paste drafting”. The result is many spelling, grammatical and cross-referencing errors and important legal issues left unclear.’

The second was also typical Khaiyum – putting himself as Minister, his Decree, and the operation, judgement, pricing determinations and penalties of his Commerce Commission above reproach, beyond judicial review and forever set in stone (even to survive the 2014 elections).

38A. - (1) No Court, tribunal, commission or any other adjudicating body shall have the jurisdiction, to accept, hear, determine or in any other way entertain, any challenges whatsoever (including any application for judicial review) by any person or body, or to award any compensation or grant any other remedy to any person or body, in relation to the validity or legality or propriety or any action or decision of the Minister or the Commerce Commission in making a Price Control Order under either section 39, 40, 44, 45 and Part 5A of the Decree or any action or decision resulting from making such an Order.

(2) Any legal proceeding, appeal or application of any form whatsoever, seeking to challenge the validity or legality of a Price Control Order made under either section 39, 40, 44, 45 and Parts 5A of the Decree or any action or decision resulting from making such an Order shall wholly terminate immediately upon the commencement of this Decree, and a Certificate to that effect shall be issued by the Chief Registrar, tribunal, commission or other relevant adjudicating body to all parties to the proceeding or application.

The impact of this ‘Infallibility clause’ was what most alarmed Munro Leys about the new Khaiyum legal vehicle which still to this day has the potential to control the price of pretty much anything, without any form of judicial oversight:

‘More concerning is the increasing number of Commission decisions that the Decree says may not be challenged. Public law decision-makers are far from infallible. People affected by their bad decisions should have legal redress. If not, the only way bad decisions can be changed is by lobbying for new decisions. The consequences for good governance are self-evident.’

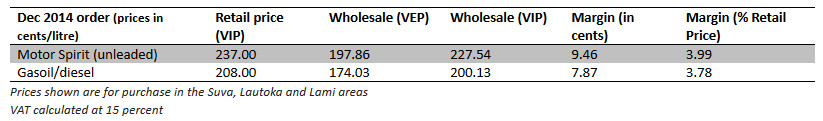

In the case of Khaiyum and his meddling in the fuel market those warnings about good governance are all too prescient. The first two columns are the figures that appear in the Commerce Commission decree relating to the Suva and Lautoka conurbations – the country’s largest fuel retail market – and came into effect in December 2014. The remaining columns have been calculated by FijiLeaks (Margin in cents is calculated by Retail VIP minus Wholesale VIP; and Margin % is Margin in cents as a proportion of Retail Price VIP in percentage terms).

http://www.commcomm.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Fuel-Order-Schedules-December-2014.pdf

The public announcement of the rise in fuel margin of 3.78 and 3.99 percent for diesel and unleaded respectively was made to the public by Khaiyum, although Khaiyum himself is no longer the minister responsible for the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism into which the Commerce Commission reports. Why was it Khaiyum who was talking to the media about a fuel order pricing determination of a supposedly independent statutory body under the responsibility of a different minister altogether? [The correct minister would have been Faiyaz Koya, the Lautoka lawyer who polled only 875 votes but still won a seat in Parliament.]

That the Minister of Finance should still be meddling in the fuel market, well beyond his current ministerial brief, is directly linked to the Tappoo Group’s recent entrée into the Fiji fuel market and the kleptocracy at heart of the Bainimarama – Khaiyum regime. In September 2013 Tappoo Group took over from Carpenters the running of 16 Mobil-branded fuel stations. This acquisition took the controversial and regime-friendly Sigatoka-based company from nowhere to suddenly being Fiji’s biggest fuel distributor. Carpenters were giving up because, just as with BP Oil in 2008, government-mandated post-coup fuel margins had been too low for too long to make a reasonable commercial return.

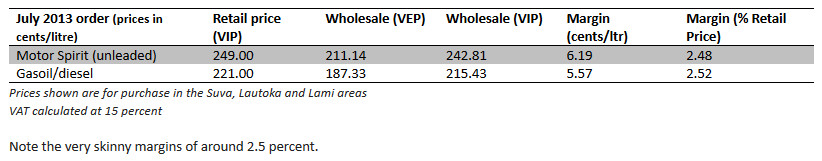

Carpenters’ decision brought an abrupt to an end more than 100 years of Mobil fuel being sold through Carpenters and Carpenters-owned Morris Hedstrom outlets around the country. At the time of the negotiations with Carpenters the fuel price orders set by the Commerce Commission were as below. Unlike in December 2014 when Khaiyum no longer had ministerial line responsibility for the Commerce Commission, these 2013 prices were recommended by the commissioners (handpicked by Khaiyum) to Khaiyum as the Minister, and he formally approved.

Maybe not a spectacularly vast increase to the untrained eye, but consider this.

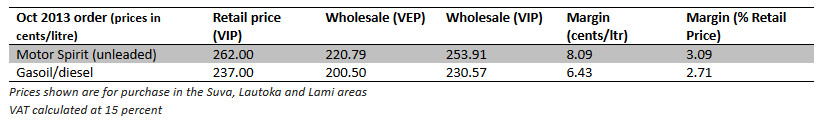

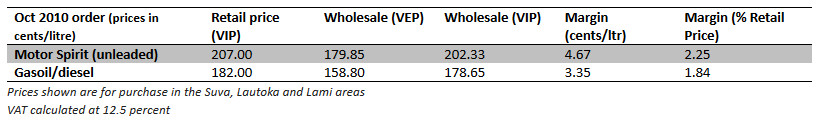

1. If you compare the pre-Tappoo October 2010 order, shown below, with the pre-Tappoo July 2013 order above – it took a total of 34 months for the Commerce Commission to agree to lift the margin on unleaded fuel from 2.25 percent to 2.48 (less than a quarter of a percent) and 1.84 percent to 2.52 (just over two-thirds of a percentage point). As soon as Tappoo enters the fuel market, it takes the Commerce Commission less than three weeks to pile on almost three-fifths of a percent to the margin on unleaded and a fifth of a percent for diesel.

As you can see by contrasting the first Tappoo-friendly October 2013 order with the December 2014 order – after years of flat-lining, now the direction of the margins is headed only one way, and has accelerated through each subsequent order at a much steeper rate of increase than was ever provided since the Executive Authority Decree 2009 and in the years that followed the 2006 coup.

Would Carpenters (and even BP Oil) have sold out to a regime-friendly company like Tappoo Group and ended more than a century of fuel supply to the Fiji consumer, if they had known the fuel margins would rise so significantly over the short term?

What this means in practical terms today is as follows: a consumer filling his or her car with unleaded petrol in the Suva, Lautoka, Lami area in January 2015 is paying only $2.37 per litre at the pump because of falling global oil prices, but a rising 4 percent margin or 9.46 cents profit per litre because of Khaiyum’s willingness to hide a greater profit margin to Tappoo inside the supposed good news of cheaper fuel at the petrol station.

Eighteen months earlier (and before Tappoo had entered the market) the purchase price was higher under the July 2013 fuel price order ($2.49 per litre) but the margin within that higher price was lower at 6.19 cents per litre or 2.48 percent.

Yet for most of this government’s time in office, Khaiyum and his puppets in the Commerce Commission have energetically blocked any hint of a meaningful increase – even if this cost hundreds of jobs of the low-skilled workers whose employment opportunities are most limited in the struggling post-2006 coup economy.

To understand how cynical Khaiyum has been with the fuel margin rate you only need to go back to the October 2010 fuel orders: That same month, October 2010, the Fiji Fuel Retail Association announced that, after almost four years of frustration dealing with the Khaiyum price regime, its member companies would be cutting 400 low-skilled jobs at 74 service stations across the country as the industry moved to self-service from attendant service. The FRRA said that its membership could not afford to pay for forecourt staff at government-set profit margins that were 1.84 percent for diesel and 2.25 for unleaded.

"This is a major cost-cutting move by our members to ensure the survival of a vital local industry," Association president Baljeet Singh told the Fiji Times at the time. "We are victims of a price control system that is squeezing the life out of our businesses.” Unfortunately the FRRA was speaking the common-sense of hard facts and basic economics – about which the statist, anti-business Khaiyum knows little and cares for even less.

Only when self-interest raises its head - see FBC vs Fiji TV, One Hundred Sands Ltd, Tappoo’s fuel company etc., - is Khaiyum ready to act, long after the 400 jobs have been lost and the irreversible process of automation begun, and only then using money picked from the pockets of Fiji’s most hard-pressed to help his rich pals.