"For whatever problems he may have faced and even generated himself, there is little doubt that Dr. Ganesh Chand has improved the provision of tertiary education to the poorest communities in Fiji, regardless of their ethnicity, religion and region, and broadened the choice of academic outlets for research and publications, great entrepreneurial achievements" |

Narsey

Narsey Most entrepreneurs try to make money. They usually take a risk in creating and owning their business, put up their own capital or borrow; they make the decisions to employ, promote, demote or fire the staff; they decided on what to produce and how; they decide on who to sell to; and they are also entitled to any profits being made, and liable for all debts (usually).

But an academic entrepreneur starting a university is not out to make money. Moreover, he has none of the advantages that the typical business entrepreneurs have.

With most universities, some country or organization owns the land and capital assets; some board or other has a role in hiring and firing; choosing the outputs of the university; deciding on which market to sell to or not; and probably most important of all, it can be totally vulnerable to the government of the day, or survive because of taxpayer funds.

Dr. Ganesh Chand has been centrally involved in the establishment of two universities- Fiji National University (FNU) and Fiji University (UniF).

He has been requested to give advice on the establishment of at least two other universities around the region (one in Solomon Islands and one in Timor Leste).

Ganesh has also been the driving force behind the establishment of two academic journals, one extremely successful (Fijian Studies) and one recently published (Pacific Journal of Education) whose success is yet to be seen.

He started a printing press in Lautoka to expedite the publication of his journals which would have been too costly otherwise.

Like the typical dynamic entrepreneur, he keeps thinking of new academic ventures all the time- some reasonable and some apparently difficult- like a Girmit Research Centre– until it works.

Of course, Ganesh has had to deal with the usual problems that entrepreneurs face: start-up capital, skilled human resources, market demand, quality of product, and even uncalled for political problems.

There are many sides to the energetic Dr. Ganesh Chand that this article does venture into, such as his role as a “typical politician” in Fiji, or the current charges he is facing in court. This article focuses purely on his role as a very successful academic entrepreneur.

For whatever problems he may have faced and even generated himself, there is little doubt that Dr. Ganesh Chand has improved the provision of tertiary education to the poorest communities in Fiji, regardless of their ethnicity, religion and region, and broadened the choice of academic outlets for research and publications, great entrepreneurial achievements.

His poor origins but commitment

Ganesh Chand was born of poor cane farming parents in Labasa, like several other well known academic achievers such as Professor Brij Lal, Professor Biman Prasad, and Professor Subramani. But what distinguishes Ganesh (and Biman) from most other USP graduates is his passionate commitment to Fiji.

As a good economics graduate with Bachelors and Masters from USP, and a PhD from a very good American university (New School for Social Research, New York) Ganesh could have easily emigrated to Australia or New Zealand or Canada and worked for twice the salary that he has received in Fiji. or worked for five times his Fiji salary with many of the international organizations such as Asian Development Bank or World Bank.

Not only was Ganesh one of my better undergraduate students at USP, but he also did an excellent Master’s thesis, supervised by myself and John Samy (then Director of Central Planning Office), on a Cost Benefits revaluation of the Suva-Nadi highway.

This thesis, available at the USP Library, ought be compulsory reading for all economics students in Fiji wanting to do evaluation of the many multi-million dollar projects that have been implemented willy-nilly in the last ten years.

Ganesh’s love of academia no doubt started at USP which he joined as a Lecturer in Economics soon after graduating around 1980. He taught and published actively in USP’s flagship Journal of Pacific Studies.

He also joined our hard fought battles for regionalization at USP, alongside Dr. Yadhu Nand Singh, the late Dr. Ropate Qalo, Professor Rajesh Chandra and yours truly.

Like many USP academics before him, Ganesh also tried to serve the people of Fiji in the Fiji Parliament.

While successful as a Fiji Labour Party candidate, his contribution as a Minister (and those of many good FLP party colleagues) was cut short by the 2000 coup while he also endured fifty six traumatic days as a hostage of the Speight Group (and shadowy leaders behind the scenes).

Concern for poor university students

Few young people today will remember the battles that poor Indo-Fijian students faced to get to USP two decades ago, before the Bainimarama Government eased up the pathways. Even if they were qualified to do so, they could not get scholarships and they were too poor to pay USP’s “full economic fee”.

Ganesh Chand and a small group of USP academics (Professor Biman Prasad, Dr. Surendra Prasad, Dr. Sunil Kumar, Dr. Som Prakash and a few others) formed the Fiji Youth and Students’ League (FYSL) and to offer financial assistance (largely through personal donations and “goat and gallon” parties) to poor students to enter USP.

But such charity was not a long term solution to the tertiary education needs of the poor and it was clear to many that a cost-effective alternative to USP was needed. Ganesh took up the challenge to create an alternative Fiji university.

There was little support from the governments of the day for whom the education of poor Indo-Fijians was not a priority, while a few racist individuals in power even tried to put their spanners into the works.

Hindu religious organizations such as Sanatan Dharam and Sangam had ambivalent attitudes to Ganesh’s proposal for a new university in the West, some having their own plans for tertiary institutes and some opposed out of inertia or sheer cussedness.

Powerful business leaders in the Indo-Fijian community (including some sitting on university councils) would not help (unless there was money to be made for themselves).

Ganesh plowed on regardless and eventually received support from the more enlightened Arya Samaj. The Fiji University was born but struggled to get established, with minimal government support and limited revenue streams because of paucity of student numbers.

Fortuitous for Fiji University’s future was their staffing appointment of Filipe Bole, a former Education Minister and diplomat under the Mara Governments, who would later return the favor as Minister of Education under the Bainimarama Government.

From the beginning FU struggled to provide quality education, for many obvious reasons similar to that faced later by FNU: with uncompetitive salaries, they had difficulty in appointing quality staff ; the had difficulty in attracting the best students; they mounted a costly law program and other costly ones just did not have the economies of scale; and they even made strategically poor decisions to locate a second campus in Suva rather than the densely populated Nasinu and Nadera areas which would have been happier hunting grounds for higher enrolments.

For reasons that probably deserve some other researchers’ attention, Ganesh Chand moved on from Fiji University and was replaced by Professor Rajesh Chandra who was then being pushed out from USP (another story).

Fiji National University

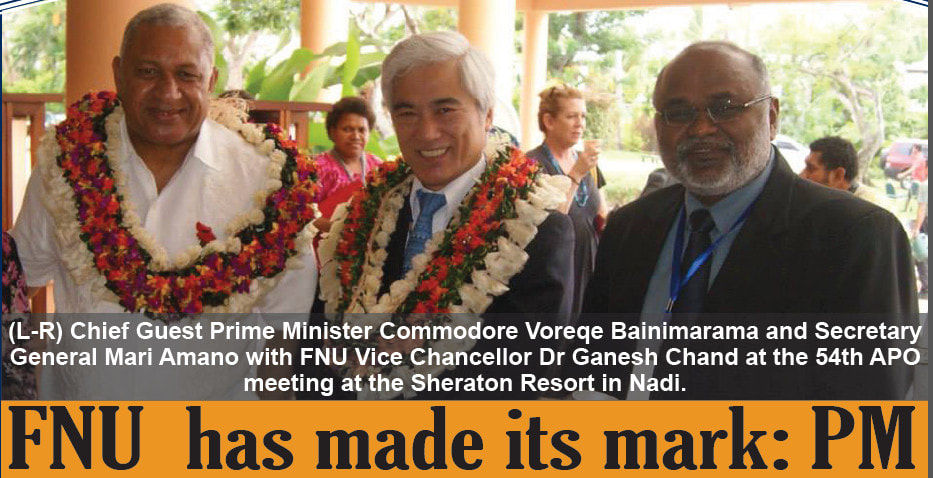

Ganesh Chand will probably be remembered most for his establishment of the Fiji National University, larger now in enrolments than the University of the South Pacific established fifty years earlier.

No doubt the creation and success of FNU owes its origins to the 2006 military coup by Bainimarama, since it provided an alternative university to USP, then home to several aggressive critics of his military coup and government.

On the surface it may have seemed easy and logical to form FNU by just combining all the government-owned tertiary institutions such as Fiji Institute of Technology (FIT), Fiji School of Medicine (FSM), Fiji Nursing College (FNC), Fiji College of Agriculture (FCA), Lautoka Teachers’ College (LTC), Fiji National Training Council (FNTC), and others.

On paper, there could be consolidation of many courses common to all the institutions, such as English language and literatures, mathematics, sciences, and social sciences. Economies of scale and scope were theoretically possible hopefully pushing down unit costs. Some, like FNTC, brought generous guaranteed funding from employers.

But there was much opposition from the management of the institutions themselves. FSM, for instance, was the oldest tertiary institution in the Pacific with a well-deserved regional reputation. Indeed, all the different managements naturally worried about the dilution of their control (“turf issues”) and some worried about the likely impact on quality and strategic directions.

While a few resented having an Indo-Fijian vice chancellor, this cut no ice with Bainimarama, Khaiyum or Filipe Bole with Ganesh Chand (with Mahendra Reddy) already having an inside track with them as useful back-stage policy adviser in the early years of the coup.

Any opposition was squashed, with the Bainimarama Government fully supporting whatever consolidation, appointments and redeployments wanted by Ganesh, while increasing grants and appointing active council members.

Of course, FNU had long maintained reasonable quality in the technical and vocational diplomas and certificates traditionally provided by the constituent colleges.

But FNU also began to increase its offerings in the more “academic” areas, aggressively competing with USP: to most students and parents, a BA is a BA and a BCom is a BCom. regardless of where it is derived, since having access is their greatest concern- not quality.

There is enormous scope for the Fiji Higher Education Commission to do through and constructive research on the impact of Fiji National University on a number of key areas: access for poor students; quality of student intake; quality of staff and requisite salary scales; quality of programs both academic and technical; employment outcomes of graduates, locally and internationally; impact on research and development in Fiji; impact of increased competition from USP’s TAFE courses; employers’ assessment of FNU graduates program by program; funding from donors, government and students themselves; and many other areas of concern.

What is unchallengeable however is that with the establishment of FNU there has been a remarkable increase in the number of tertiary graduates entering the labor market, both in Fiji and abroad, without whom Fiji would have been facing severe and crippling shortages of skilled human resources because of the continuing high rates of emigration.

Other universities

It might seem odd that aid-flooded countries like Solomon Islands and Timor Leste have consulted Fiji’s Dr. Ganesh Chand for establishing their own universities.

But I suspect that the politicians and Ministry of Education officials in Solomon Islands and Timor Leste are mindful of having cost-effective universities of the kind that Fiji has produced, with unit costs much lower that those prevailing in Australian and NZ universities.

These countries probably also know that relying totally on donor funded projects will probably lead to relative more expensive universities with costly staff mostly hired from the donor countries.

Two new academic journals

A few years ago, Ganesh who by that time had left USP, began a new academic journal, Fijian Studies.

There was a predictable outcry from those who felt that the word “Fijian” should only be used for things “indigenous Fijians”. Why not call it The Journal of Fiji Studies.

But a political point was being made by Ganesh and his collaborators and the Bainimarama Government’s insistence on using the word “Fijian” to describe all Fiji citizens and its acceptance by some indigenous Fijian leaders like Ro Temumu Kepa, has shelved that debate.

Another criticism was that there already existed the Journal of Pacific Studies at USP to which all Fiji academics “theoretically” had access to. I say “theoretically”, because this journal (of which I also have been an editor in previous decades), did not always allow full exposure of Fiji articles, depending on the editor at the time, the authors and the content of the articles.

But with Ganesh able to convince many established academics to sit on the board, Fijian Studies began to publish many articles which otherwise would not have got into print.

One unfortunate and ironic side effect of USP staff involvement in the success of Fijian Studies, was that the Journal of Pacific Studies went into hibernation for several years around 2005, until re-energized after I had rejoined USP in 2008.

Another great act of academic entrepreneurship by Ganesh is the publication of the first volume of the Journal of Pacific Education, an attempt to fill a vacuum left by the failure of USP’s School of Education to maintain the frequency and quality of their education journal.

No doubt the success of this journal will depend on the support of educationists in the region and not just those in Fiji.

For both journals, Ganesh has had to overcome major hurdles of getting established academics in Fiji and internationally to agree to go on to the Boards and Councils, as well as contribute refereed articles which are then published with some degree of quality.

While these are difficult tasks even for journals based in large universities and drawing on large academic departments, they are herculean tasks for an isolated under-resourced academic in a small country like Fiji.

Their coming into print is a great testament to the ability and energy of Ganesh Chand to evince the participation of many academic collaborators.

While quality will always be a challenge for small populations, the bottom line is that now there is much great competition among journals for budding academics and researchers to publish scholarly articles.

Less monopoly on the control of ideas and their dissemination is surely good for Fiji and the Pacific in general.

More to entrepreneurship than making money

While there can always be improvements in the overall quality of new universities and journals, a beginning has been made and it is surely up to the academics and researchers in Fiji and the Pacific to build on Ganesh’s efforts and take collective responsibility.

Few Fijians (however defined) can match the record that Dr. Ganesh Chand has as an academic entrepreneur: starting two universities, advising on two other Pacific Island ones, and starting two academic journals. He has advised Government on institutions to better regulate the tertiary education sector. He has more initiatives in the pipeline such as the Global Girmit Institute and Girmit Studies.

Dr. Ganesh Chand’s achievements demonstrate to Fiji and especially our youth seeking employment that entrepreneurship in the world of ideas can do more to transform society than entrepreneurship that just seeks to make money.

Postscript: The woman behind the man

It is generally true that llike most of our entrepreneurs, male or female, there is usually an equally strong and supportive partner behind the scene. In Ganesh’s case she is Dr Premila Devi, USP Center Director at Lautoka.

A critical element in Ganesh’s family foundation, Premila is a quiet professional in her own right, while shunning the limelight. Also one of my students at USP, Premila would be a great research topic for some gender studies student exploring the quiet leadership roles played by Indo-Fijian women with poor rural origins, like Premila.

But an academic entrepreneur starting a university is not out to make money. Moreover, he has none of the advantages that the typical business entrepreneurs have.

With most universities, some country or organization owns the land and capital assets; some board or other has a role in hiring and firing; choosing the outputs of the university; deciding on which market to sell to or not; and probably most important of all, it can be totally vulnerable to the government of the day, or survive because of taxpayer funds.

Dr. Ganesh Chand has been centrally involved in the establishment of two universities- Fiji National University (FNU) and Fiji University (UniF).

He has been requested to give advice on the establishment of at least two other universities around the region (one in Solomon Islands and one in Timor Leste).

Ganesh has also been the driving force behind the establishment of two academic journals, one extremely successful (Fijian Studies) and one recently published (Pacific Journal of Education) whose success is yet to be seen.

He started a printing press in Lautoka to expedite the publication of his journals which would have been too costly otherwise.

Like the typical dynamic entrepreneur, he keeps thinking of new academic ventures all the time- some reasonable and some apparently difficult- like a Girmit Research Centre– until it works.

Of course, Ganesh has had to deal with the usual problems that entrepreneurs face: start-up capital, skilled human resources, market demand, quality of product, and even uncalled for political problems.

There are many sides to the energetic Dr. Ganesh Chand that this article does venture into, such as his role as a “typical politician” in Fiji, or the current charges he is facing in court. This article focuses purely on his role as a very successful academic entrepreneur.

For whatever problems he may have faced and even generated himself, there is little doubt that Dr. Ganesh Chand has improved the provision of tertiary education to the poorest communities in Fiji, regardless of their ethnicity, religion and region, and broadened the choice of academic outlets for research and publications, great entrepreneurial achievements.

His poor origins but commitment

Ganesh Chand was born of poor cane farming parents in Labasa, like several other well known academic achievers such as Professor Brij Lal, Professor Biman Prasad, and Professor Subramani. But what distinguishes Ganesh (and Biman) from most other USP graduates is his passionate commitment to Fiji.

As a good economics graduate with Bachelors and Masters from USP, and a PhD from a very good American university (New School for Social Research, New York) Ganesh could have easily emigrated to Australia or New Zealand or Canada and worked for twice the salary that he has received in Fiji. or worked for five times his Fiji salary with many of the international organizations such as Asian Development Bank or World Bank.

Not only was Ganesh one of my better undergraduate students at USP, but he also did an excellent Master’s thesis, supervised by myself and John Samy (then Director of Central Planning Office), on a Cost Benefits revaluation of the Suva-Nadi highway.

This thesis, available at the USP Library, ought be compulsory reading for all economics students in Fiji wanting to do evaluation of the many multi-million dollar projects that have been implemented willy-nilly in the last ten years.

Ganesh’s love of academia no doubt started at USP which he joined as a Lecturer in Economics soon after graduating around 1980. He taught and published actively in USP’s flagship Journal of Pacific Studies.

He also joined our hard fought battles for regionalization at USP, alongside Dr. Yadhu Nand Singh, the late Dr. Ropate Qalo, Professor Rajesh Chandra and yours truly.

Like many USP academics before him, Ganesh also tried to serve the people of Fiji in the Fiji Parliament.

While successful as a Fiji Labour Party candidate, his contribution as a Minister (and those of many good FLP party colleagues) was cut short by the 2000 coup while he also endured fifty six traumatic days as a hostage of the Speight Group (and shadowy leaders behind the scenes).

Concern for poor university students

Few young people today will remember the battles that poor Indo-Fijian students faced to get to USP two decades ago, before the Bainimarama Government eased up the pathways. Even if they were qualified to do so, they could not get scholarships and they were too poor to pay USP’s “full economic fee”.

Ganesh Chand and a small group of USP academics (Professor Biman Prasad, Dr. Surendra Prasad, Dr. Sunil Kumar, Dr. Som Prakash and a few others) formed the Fiji Youth and Students’ League (FYSL) and to offer financial assistance (largely through personal donations and “goat and gallon” parties) to poor students to enter USP.

But such charity was not a long term solution to the tertiary education needs of the poor and it was clear to many that a cost-effective alternative to USP was needed. Ganesh took up the challenge to create an alternative Fiji university.

There was little support from the governments of the day for whom the education of poor Indo-Fijians was not a priority, while a few racist individuals in power even tried to put their spanners into the works.

Hindu religious organizations such as Sanatan Dharam and Sangam had ambivalent attitudes to Ganesh’s proposal for a new university in the West, some having their own plans for tertiary institutes and some opposed out of inertia or sheer cussedness.

Powerful business leaders in the Indo-Fijian community (including some sitting on university councils) would not help (unless there was money to be made for themselves).

Ganesh plowed on regardless and eventually received support from the more enlightened Arya Samaj. The Fiji University was born but struggled to get established, with minimal government support and limited revenue streams because of paucity of student numbers.

Fortuitous for Fiji University’s future was their staffing appointment of Filipe Bole, a former Education Minister and diplomat under the Mara Governments, who would later return the favor as Minister of Education under the Bainimarama Government.

From the beginning FU struggled to provide quality education, for many obvious reasons similar to that faced later by FNU: with uncompetitive salaries, they had difficulty in appointing quality staff ; the had difficulty in attracting the best students; they mounted a costly law program and other costly ones just did not have the economies of scale; and they even made strategically poor decisions to locate a second campus in Suva rather than the densely populated Nasinu and Nadera areas which would have been happier hunting grounds for higher enrolments.

For reasons that probably deserve some other researchers’ attention, Ganesh Chand moved on from Fiji University and was replaced by Professor Rajesh Chandra who was then being pushed out from USP (another story).

Fiji National University

Ganesh Chand will probably be remembered most for his establishment of the Fiji National University, larger now in enrolments than the University of the South Pacific established fifty years earlier.

No doubt the creation and success of FNU owes its origins to the 2006 military coup by Bainimarama, since it provided an alternative university to USP, then home to several aggressive critics of his military coup and government.

On the surface it may have seemed easy and logical to form FNU by just combining all the government-owned tertiary institutions such as Fiji Institute of Technology (FIT), Fiji School of Medicine (FSM), Fiji Nursing College (FNC), Fiji College of Agriculture (FCA), Lautoka Teachers’ College (LTC), Fiji National Training Council (FNTC), and others.

On paper, there could be consolidation of many courses common to all the institutions, such as English language and literatures, mathematics, sciences, and social sciences. Economies of scale and scope were theoretically possible hopefully pushing down unit costs. Some, like FNTC, brought generous guaranteed funding from employers.

But there was much opposition from the management of the institutions themselves. FSM, for instance, was the oldest tertiary institution in the Pacific with a well-deserved regional reputation. Indeed, all the different managements naturally worried about the dilution of their control (“turf issues”) and some worried about the likely impact on quality and strategic directions.

While a few resented having an Indo-Fijian vice chancellor, this cut no ice with Bainimarama, Khaiyum or Filipe Bole with Ganesh Chand (with Mahendra Reddy) already having an inside track with them as useful back-stage policy adviser in the early years of the coup.

Any opposition was squashed, with the Bainimarama Government fully supporting whatever consolidation, appointments and redeployments wanted by Ganesh, while increasing grants and appointing active council members.

Of course, FNU had long maintained reasonable quality in the technical and vocational diplomas and certificates traditionally provided by the constituent colleges.

But FNU also began to increase its offerings in the more “academic” areas, aggressively competing with USP: to most students and parents, a BA is a BA and a BCom is a BCom. regardless of where it is derived, since having access is their greatest concern- not quality.

There is enormous scope for the Fiji Higher Education Commission to do through and constructive research on the impact of Fiji National University on a number of key areas: access for poor students; quality of student intake; quality of staff and requisite salary scales; quality of programs both academic and technical; employment outcomes of graduates, locally and internationally; impact on research and development in Fiji; impact of increased competition from USP’s TAFE courses; employers’ assessment of FNU graduates program by program; funding from donors, government and students themselves; and many other areas of concern.

What is unchallengeable however is that with the establishment of FNU there has been a remarkable increase in the number of tertiary graduates entering the labor market, both in Fiji and abroad, without whom Fiji would have been facing severe and crippling shortages of skilled human resources because of the continuing high rates of emigration.

Other universities

It might seem odd that aid-flooded countries like Solomon Islands and Timor Leste have consulted Fiji’s Dr. Ganesh Chand for establishing their own universities.

But I suspect that the politicians and Ministry of Education officials in Solomon Islands and Timor Leste are mindful of having cost-effective universities of the kind that Fiji has produced, with unit costs much lower that those prevailing in Australian and NZ universities.

These countries probably also know that relying totally on donor funded projects will probably lead to relative more expensive universities with costly staff mostly hired from the donor countries.

Two new academic journals

A few years ago, Ganesh who by that time had left USP, began a new academic journal, Fijian Studies.

There was a predictable outcry from those who felt that the word “Fijian” should only be used for things “indigenous Fijians”. Why not call it The Journal of Fiji Studies.

But a political point was being made by Ganesh and his collaborators and the Bainimarama Government’s insistence on using the word “Fijian” to describe all Fiji citizens and its acceptance by some indigenous Fijian leaders like Ro Temumu Kepa, has shelved that debate.

Another criticism was that there already existed the Journal of Pacific Studies at USP to which all Fiji academics “theoretically” had access to. I say “theoretically”, because this journal (of which I also have been an editor in previous decades), did not always allow full exposure of Fiji articles, depending on the editor at the time, the authors and the content of the articles.

But with Ganesh able to convince many established academics to sit on the board, Fijian Studies began to publish many articles which otherwise would not have got into print.

One unfortunate and ironic side effect of USP staff involvement in the success of Fijian Studies, was that the Journal of Pacific Studies went into hibernation for several years around 2005, until re-energized after I had rejoined USP in 2008.

Another great act of academic entrepreneurship by Ganesh is the publication of the first volume of the Journal of Pacific Education, an attempt to fill a vacuum left by the failure of USP’s School of Education to maintain the frequency and quality of their education journal.

No doubt the success of this journal will depend on the support of educationists in the region and not just those in Fiji.

For both journals, Ganesh has had to overcome major hurdles of getting established academics in Fiji and internationally to agree to go on to the Boards and Councils, as well as contribute refereed articles which are then published with some degree of quality.

While these are difficult tasks even for journals based in large universities and drawing on large academic departments, they are herculean tasks for an isolated under-resourced academic in a small country like Fiji.

Their coming into print is a great testament to the ability and energy of Ganesh Chand to evince the participation of many academic collaborators.

While quality will always be a challenge for small populations, the bottom line is that now there is much great competition among journals for budding academics and researchers to publish scholarly articles.

Less monopoly on the control of ideas and their dissemination is surely good for Fiji and the Pacific in general.

More to entrepreneurship than making money

While there can always be improvements in the overall quality of new universities and journals, a beginning has been made and it is surely up to the academics and researchers in Fiji and the Pacific to build on Ganesh’s efforts and take collective responsibility.

Few Fijians (however defined) can match the record that Dr. Ganesh Chand has as an academic entrepreneur: starting two universities, advising on two other Pacific Island ones, and starting two academic journals. He has advised Government on institutions to better regulate the tertiary education sector. He has more initiatives in the pipeline such as the Global Girmit Institute and Girmit Studies.

Dr. Ganesh Chand’s achievements demonstrate to Fiji and especially our youth seeking employment that entrepreneurship in the world of ideas can do more to transform society than entrepreneurship that just seeks to make money.

Postscript: The woman behind the man

It is generally true that llike most of our entrepreneurs, male or female, there is usually an equally strong and supportive partner behind the scene. In Ganesh’s case she is Dr Premila Devi, USP Center Director at Lautoka.

A critical element in Ganesh’s family foundation, Premila is a quiet professional in her own right, while shunning the limelight. Also one of my students at USP, Premila would be a great research topic for some gender studies student exploring the quiet leadership roles played by Indo-Fijian women with poor rural origins, like Premila.