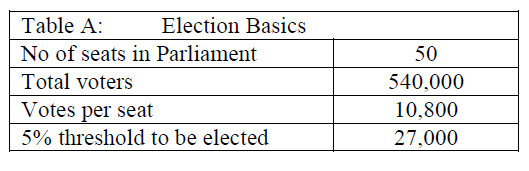

“The Electoral Commission must then disregard any total number of votes received under the name of any political party or any independent candidate that has not received a total that is at least 5% of the total number of votes received by all the political parties and independent candidates.”

I have shaded in yellow those who do not make the 5% threshold of 27,000 votes.

i.e. Party E and the Independents 2 and 3 are OUT and will not be in Parliament.

So all their votes are wasted.

Independent 1 is elected with certainty (but with 30,000 votes).

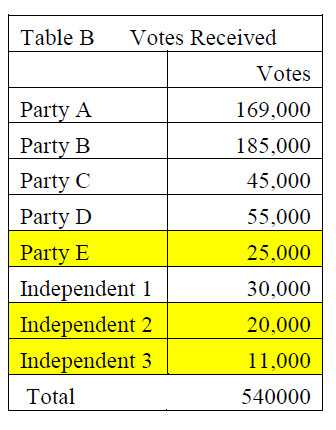

The votes of Party E and all the Independents are excluded, in calculating the numbers of candidates from the political parties A, B, C and D, eligible to go into Parliament.

Hence 49 parliamentary seats have to be allocated to Parties A, B, C and D. and strictly in proportion to the votes they have received.

Table C gives in Column (3) the exact proportions of the total votes received by Parties A, B, C and D

Column (4) gives the exact number of parliamentarians they are entitled to (including the fractions)

Column (5) gives the numbers rounded up, so as to add up to 49 exactly.

When you add the 1 Independent, you get a total of 50 required for the parliament.

Lesson 1 Parties need to be prepared for a “hung” parliament

In the particular arithmetic example I have given above (Table C), the outcome is a “hung parliament” with no Party receiving a majority of 26 out of 50. With the five parties (FFP, SODELPA, FLP, NFP, PDP) contesting, this may well be the likely outcome. For fun, readers can try various coalitions post-election, which would give a minimum of 26. Even the one Independent or the small parties might become “king-makers”: eg B, C and the Independent. But there are many other lessons that parties, candidates and voters need to consider.

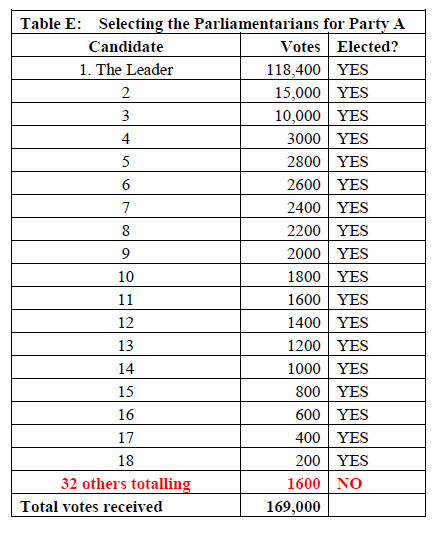

How are individual parliamentarians chosen? Because this is an “Open List” system, whatever the original List provided by the contesting parties, their candidates will be ranked by the numbers of votes they receive. (not the party ranking) Thus, if Party A is entitled to 18 seats in Parliament, then the first 18 in order of votes received will be selected.

The remain 32 candidates will not be selected (assuming that each party puts up 50 candidates).

This Open List system has the undeniable advantage that really unpopular candidates are not going to get into parliament just because they have joined a popular party. But they could still get in, if their other colleagues are equally unpopular. If voters decide to vote only for “The Leader”, then some of the minor candidates may not get enough votes to make it to the top of the List (see Table E below). Parties will have to agree with their candidate where they should campaign in order to win not just maximum votes for their party, but also for themselves as individuals. Many candidates will want to campaign only in the populous areas where there are large numbers of voters, or where they feel they have the best chance.

Few will want to campaign in widespread areas where the numbers of voters are small, and the costs of campaigning will be high.

Lesson 2 Not only will each Party be competing against other parties, but candidates within each party will also be competing against each other.

Lesson 3 Some candidates will have to “sacrifice” their own chances of being elected, in order to campaign in remote less densely populated areas, in order to win maximum votes for their parties, even if they themselves do not win.

The impact of the 5% threshold

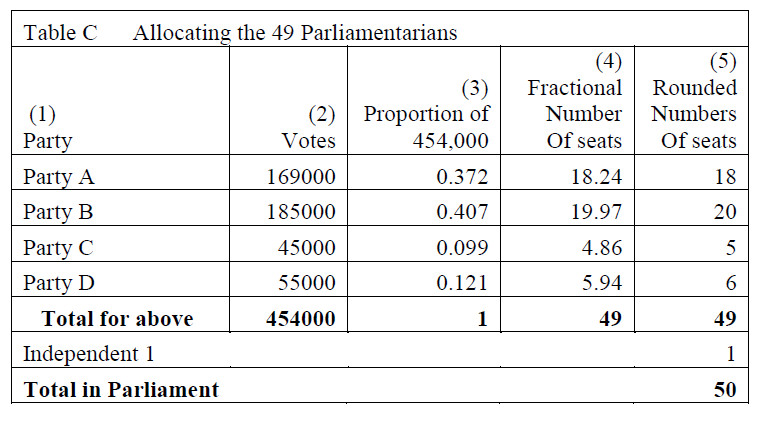

Table E shows very clearly, why the system is stacked against small parties and Independents (shown in green), because of the 5% threshold clauses in the Decree.

In the example above, all the votes for Party E and Independents 2 and 3 are totally wasted.

Even Independent 1 who gets elected (but with 30,000 votes) is wasting the votes of some 20,000 or two thirds of his/her supporters. Had these 30,000 votes gone to any party, they would have elected 3 parliamentarians.

Effectively, their loss will be gained by the larger parties. If the ultimate objective of candidates is to get into parliament and affect government policy, either as part of government or as Opposition, then Independents and small parties would be strongly advised to negotiate with the larger parties to obtain agreement on common manifestoes, and join them rather than going on their own.

Lesson 4 This system is biased against small parties and Independents: they should consider joining like-minded large parties with similar manifesto objectives.

Lesson 5 Voters must understand that at least two thirds of their votes for Independents will be wasted, even if their candidate is successful. All their votes will be wasted if the Independent does not get the minimum of 27,000. Votes.

Lesson 6: Votes for large parties will not be wasted, even if the candidate voted for does not get elected. Even these votes are amalgamated for the Party and counted towards the Party share.

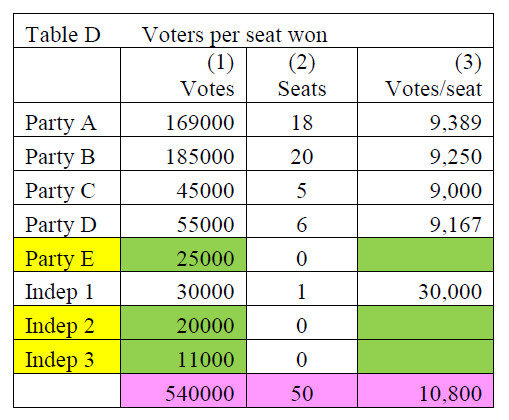

How many votes will “successful” party parliamentarians get?

Suppose that Party A is led by a nationally popular Leader and the total votes received (169,000) entitles Party A to receive 18 seats in Parliament (as in my example above).

All the candidates of Party A will be ranked in order, by the number of votes received, going down from The Great Leader down to Candidate 50 (as in Table E). In the example here, out of the 169,000 votes going to Party A, The Leader has received 118,400 votes, Candidate 2 has received 15,000, Candidate 3 has received 10,000 votes. The other 15 who get elected to Parliament received less than 3,000 votes each, going to the 18th parliamentarian, who has got only 200 votes but is elected. These fifteen (plus the first three) are all elected under the Party’s quota of 18 seats in Parliament, largely because of the large number of votes garnered by the Leader. (Note: this weakness would apply equally to a “Closed List” system)

But the fact remains that the Electoral Decree, disqualifies Independents and candidates for all small Parties who receive less than the 5% threshold (less than around 27,000) even if they receive far more than those elected under the umbrella of Party votes.

In the example below, 17 out of the first 18 would not have been elected as Independents.

Women are unlikely to be represented fairly

Under the Closed List system (which most Parties had advocated to the Ghai Commission), women could have had a reasonable chance of being placed at the top of the different Party Lists and hence automatically elected, as part of their party quota.

But with the Open List system, women are back to the same situation they had with previous elections.

Given the harsh campaigning requirements, and the unwillingness of voters (both men and women) to vote for women candidates, good women candidates are unlikely to stand, and if they do, unlikely to be elected in reasonable numbers.

The one saving grace with the one national constituency is that good women candidates (as with good men candidates) will be able to appeal to all voters in Fiji and accumulate reasonable numbers of votes.

Lesson 8 Women candidates, in addition to espousing their good party policies, need to appeal especially to women voters (who comprise 50% of all voters), to vote for good women candidates, whose policies they agree with.

See:http://narseyonfiji.wordpress.com/2014/03/31/election-issues-bulletin-7-the-2013-bkc-open-list-system-professor-wadan-narsey-31-march-2014/