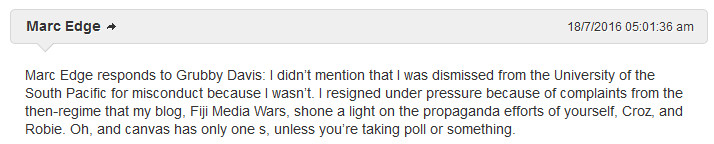

EDGE accused of writing out of his script his sacking for alleged misconduct at USP; he claims he was not SACKED but resigned due to political pressure piled on him because of his blog Fiji Media Wars

"I am monumentally indifferent to Marc Edge and his fate. This is academic dishonesty piled onto the chronic dishonesty of his other writings. I note that he doesn’t mention that he was dismissed from the University of the South Pacific for misconduct. Nor does he mention the astonishing attack on his credibility by David Robie, the region’s only journalism professor, in his article "The Lies of Marc Edge. 'Counter propagandist’." This is all an attempt, with a selective use of the truth, to punish me, Croz Walsh or anyone else who had the temerity to puncture his overweening ego and expose his humiliating treatment of his students at USP. The Qorvis angle merely gives him a global canvass on which to paint his sordid little personal vendetta." - GRAHAM DAVIS to Fijileaks

Digital buturaki: Government-sponsored blogs assail critics of Fiji’s military dictatorship

By Marc Edge, Ph.D.

University Canada

West

Vancouver

A PAPER PRESENTED TO THE WORLD JOURNALISM EDUCATION CONGRESS, JULY 14-16, 2016, AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND

A series of coups beset Fiji following its independence from Great Britain in 1970. Some blamed the press, segments of which had been critical of the government, for fomenting a coup in 2000 (Singh, T.R., 2011). According to Robie (2003: 104), ‘Many powerful institutions, such as the Methodist Church in Fiji, and politicians in the Pacific believe there is no place for a Western-style free media and it should be held in check by Government legislation’.

Self-regulation of the press by the Fiji Media Council was criticized as ineffective (Robie, 2004). A clampdown on press freedom by the military, which took control of the country in a 2006 coup, saw a new type of publication emerge in response. Enabled by websites such as blogger.com which offered free software and hosting of personal diaries, web logs or ‘blogs’ became popular at the millennium. Pro-democracy blogs in post-coup Fiji were almost exclusively anonymous, however, as anyone caught spreading anti-government sentiment risked being arrested and beaten by the military. It detained several suspected bloggers and also put pressure on the country’s telecommunications provider Fintel to block blogger.com. In response, a group of bloggers from New Zealand offered to host Fijian blogs on their servers (Fiji Times, 2007).

According to Foster, by cracking down on press freedom, the military ‘unleashed’ the blogs. The resulting ‘public relations nightmare’, she concluded, proved worse for the regime’s image than a free press would have.

The blogs’ no-holds-barred approach to military criticism picked holes in media coverage of the crisis, with blogs running stories detailing alleged military abuse as well as releasing several confidential documents (Foster, 2007: 47–48). Not all political blogs in post-coup Fiji were anti-regime, however. In early 2009, New Zealand resident Crosbie Walsh began a blog he called Fiji: The Way it Was, Is and Can Be, partly in response to what he saw as biased reporting on Fiji in the mainstream media of his country. A retired professor from the University of the South Pacific (USP) in Fiji,Walsh also published a study in 2010 which catalogued 72 known political blogs in Fiji, of which 42 were active. ‘Fifty-three were anti [- government] – 19 extremely so; 15 were more or less ‘neutral’, and three were pro government’ (Walsh, 2010: 164).Walsh deemed his own blog ‘mildly pro government’, compared to blogs such as Coup 4.5, which actively incited unrest. ‘The anti-government blogs, hailed by coup opponents as advocates of democracy, are little more than agents of uncritical dissent’ (Walsh, 2010: 174). Coup 4.5 was among the most popular blogs, notedWalsh, with a ‘staggering’ 60,000 visitors in November 2009 compared with 30,000 visitors to his own blog over a longer period (Walsh, 2010: 158).

In April 2009, Fiji’s Appeal Court ruled the 2006 coup unconstitutional, prompting the government to abrogate the constitution, sack the judiciary, declare martial law, and clamp down on civil rights. Several foreign journalists were deported and censors were installed in newsrooms to prevent negative news about the government being published. Blog activity spiked in an attempt to fill the news vacuum, prompting a renewed government crackdown. The pro-regime blog Real Fiji News published the names of several prominent Suva residents it claimed were behind the anti government blog Raw Fiji News, including the editor of the Fiji Times and three Suva lawyers, who were arrested and detained briefly for questioning (Merritt, 2009). In 2010, the regime appointed former Fairfax Media advertising executive Sharon Smith Johns as Permanent Secretary for Information, making her admittedly the country’s ‘chief censor and media strategist’ (Davis, 2010). A Media Industry Development Decree (Media Decree) was enacted by the military government the same year. It provided for fines of up to F$1,000 for journalists found in contravention of its guidelines, which increased to F$25,000 for publishers or editors and F$100,000 for media organisations (Foster, 2010; Singh, S. 2010).

In February 2011, Australian journalist Graham Davis began a blog he called Grubsheet after his production company Grubstreet. It covered a range of topics for its first year, but by early 2012 it began to focus on Fiji politics almost exclusively. Davis, who was born in Fiji, began that focus with a blog entry that criticised Coup 4.5 for alleging that Muslims were ‘colonising’ Fiji at the behest of Bainimarama’s right-hand man, Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum, who was a Muslim. ‘This grubby little offering isn’t just inflammatory but utterly false’, wrote Davis. ‘Simply put, Coup 4.5 – with this base offering – has become the local equivalent of a Nazi hate sheet’ (Davis, 2012a). The blog entry was reprinted in the pro-regime Fiji Sun newspaper, as well as on Auckland University of Technology’s Pacific Scoop and Pacific Media Centre websites, and on the blogs of Walsh and AUT journalism educator David Robie. ‘Who are these people?’ asked Davis of the contributors to Coup 4.5. A few wrote under their own names, he noted, including former Fiji Sun investigative reporter Victor Lal, who lived in England, and economist Wadan Narsey, who had been forced to resign his teaching position at the USP as a result of his outspoken opposition to the military government. Most, noted Davis, did not.

They’re always anonymous but are said to be a group of Fiji journalists running their site out of Auckland, with contributions from members of the deposed SDL government, ex civil servants and a hard core of antiregime

‘human rights’ advocates. . . . The wonder is that some of 4.5’s content is written by respected journalists and academics who are Indo-Fijians to boot (Davis, 2012a).

Qorvis Communications

In October 2011, the Fiji regime contracted with U.S. public relations company Qorvis Communications at a cost of US$40,000 per month. According to Bainimarama (2011), the purpose was ‘to assist with training and support for our Ministry of Information – to ensure its operations take into account advances in social media, the Internet and best practices regarding the media’. New Zealand journalist Michael Field, who was among the journalists barred from Fiji for reporting critically on the regime, pointed out that Qorvis had a sinister reputation in other parts of the world where it operated. ‘Qorvis specialises in putting a spin on dictators like those of Tunisia and Egypt who resisted Arab Spring. . . . Hiring Washington spin-doctors is a well-walked road for dictators who work on their image in Washington and at the United Nations’ (Field, 2011). American journalist Anna Lenzer, who had been arrested on a recent assignment to Fiji, noted in the Huffington Post ‘the Fijian junta’s exploding internet and social media presence in the weeks since Qorvis began its work’ (Lenzer, 2011).

The Huffington Post had earlier questioned the tactics employed by Qorvis on behalf of the dictatorship in Bahrain. ‘Beyond disappearing bloggers and rights activists, Bahrain also tries to disappear criticism’, it noted. ‘Most of the U.S.-based fake tweeting, fake blogging (flogging), and online manipulation is carried out from inside Qorvis Communication’s “Geo-Political Solutions” division’ (Halvorssen, 2011).

More so than intimidation, violence, and disappearances, the most important tool for dictatorships across the world is the discrediting of critics. . . . Oppressive governments are threatened by public exposure, and this means that it’s not just human rights defenders but also bloggers, opinion journalists, and civil society activists who are regularly and viciously maligned (Halvorssen, 2011). The Huffington Post also reported in 2011 that an exodus of Qorvis operatives had taken place over the firm’s unsavoury tactics and clients. In a space of two months, it noted, more than a third of the partners at Qorvis had left the firm, partly because of its work on behalf of such clients as Yemen, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Equatorial Guinea. ‘I just have trouble working with despotic dictators killing their own people’, one former Qorvis insider said (Baram, 2011).

The Fiji regime lifted martial law in early 2012, which resulted in censors exiting the country’s newsrooms. Numerous decrees, however, impinged on press freedom in addition to the Media Decree. ATV Decree enacted in 2012 permitted the minister responsible for communication to revoke the licence of any television station found to have contravened the Media Decree. It was enacted shortly after Fiji TV aired interviews with two former prime ministers who questioned the need for another new constitution. The broadcaster was reportedly then warned by the regime that its soon to- expire broadcasting licence might not be renewed as a result (Ashdown, 2012). It was, but for only six months at a time instead of the usual twelve years. Soon a campaign began against critics of the military dictatorship. Following is an analysis of issues focused on by pro-regime blogs in Fiji subsequent to the lifting of martial law in early 2012 until elections were held in September 2014.

1: Bruce Hill and Radio Australia

A favorite target of pro-regime blogs, especially Grubsheet, was reporting by Radio Australia, the foreign service of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), and its influential Pacific Beat programme. One regular target of Davis was Pacific Beat reporter Bruce Hill.When the Pacific Islands News Association (PINA) controversially held its conference in Fiji in early 2012 despite the country’s restrictions on press freedom, Davis assailed Hill’s reports of dissension at the event. ‘It’s pretty clear in the minds of conference organisers that Hill came to PINA spoiling for a fight, or at least to pursue his favoured narrative of a Pacific media umbrella in tatters by continuing division over Fiji’, Davis wrote in a blog entry that was reprinted not only in the Fiji Sun but also in The Australian (Davis, 2012b). Hill interviewed a delegate from one South Pacific country who claimed it was not the job of journalists to oppose governments, then filed a story that highlighted the comment, which drew criticism from Davis.

The AUT’s David Robie observed that without Hill’s presence, there would have been little dissention at PINA. Robie described the . . . fracas as a construct of ‘western-style conflict journalism’. Hill, he said, had set out to generate controversy by seeking a contentious opinion and then using it to generate more controversy (Davis, 2012b). Davis lodged a formal complaint with the ABC in 2013 after Pacific Beat ignored what Davis called ‘the biggest change in Australian official attitude towards Fiji’ since the 2006 coup (Davis, 2013a). Deputy Leader of the Opposition Julie Bishop gave a speech that signaled a normalising of relations with Fiji if her party came to

power in upcoming elections. ‘Here was the first significant change in official Australian attitudes towards Fiji in the six and a half years since Voreqe Bainimarama’s takeover’, blogged Davis. ‘But Radio Australia chose to ignore it.

Instead, it ran two items highly critical of the Fijian Government, both by the same reporter, Bruce Hill’ (Davis, 2013a). Davis claimed that Radio Australia was trying to subvert the political process in Australia’ by ignoring the Bishop speech. ‘The Australian taxpayer is now entitled to know . . . by whose authority Hill, and the rest

of the Radio Australia editorial team, chose to overlook a major shift in Australian attitude’ (Davis, 2013a).

It is more than a grave editorial lapse. It is also contrary to law. On the available evidence, it’s a case of the publicly funded broadcaster taking a partisan position in a manner that contravenes every aspect of the ABC’s Charter. This legally requires it – under an act of Parliament – to report without fear or favour in the interests of every Australian (Davis, 2013a).

In a subsequent blog entry, he called for an inquiry into the matter. ‘Bruce Hill needs to explain himself, as does the entire Radio Australia news team’, he wrote. ‘Because without a doubt, it is one of the most blatant instances of censorship and news manipulation Grubsheet has ever witnessed’ (Davis, 2013b). By this time, Davis had revealed he was working for Qorvis Communications on its Fiji account (Davis, 2012d). He spent much of his time in Suva working for Qorvis, he admitted, flying back and forth from his home in Sydney and staying at a leading local hotel. The admission came in September 2012, two weeks after Davis had been named host of the Southern Cross Austereo network’s weekly public affairs television programme The Great Divide (Jackson, 2012).

Yash Ghai and the Constitutional Review Commission

A Constitutional Review Commission that was tasked by the regime with drafting a new constitution for Fiji ran into difficulties throughout 2012. Yash Ghai, a University of Hong Kong law professor who headed the commission, first complained of interference from the head of the military government, then clashed dramatically with the regime at year’s end. In a November interview with Radio Australia’s Campbell Cooney, Ghai revealed there had been ‘massive interference’ by the regime with the commission’s work. ‘I get emails from the PM to do this or not to do that, and this is a kind of harassment’ (Radio Australia, 2012a). The situation came to a climax after the commission submitted its draft constitution to the government just before Christmas. Ghai ordered copies printed for distribution prior to it being considered by a special Constituent Assembly of citizens, which was planned to ratify it. Police seized the copies over Ghai’s objections, however, and incinerated several while he watched. ‘I have never been in a process where there has been such an attempt to hide the recommendations of a body which was set up by this very government’, Ghai told Hill in an interview (Radio Australia, 2012b). The regime at first denied the seizure and burning, but pictures of the incident were soon posted online. Davis was unusually silent on the issue, having recently informed readers of his blog that he was bowing out of the Fiji political fray because of his work for Qorvis. ‘I have a clear conflict of interest when it comes to commenting on political matters in Fiji, and especially partisan politics in the lead-up to the election,’ he wrote.

‘I am now spending much of my time in Suva working on the Qorvis account that services the Fijian Government’ (Davis, 2012e). Walsh accused Hill of ‘making a mountain out of a mole-hill’ and deconstructed his interview with Ghai line by line. ‘It shows how a supposedly neutral interviewer reveals his true colours’, wrote Walsh. ‘No one could possibly be in doubt about his feelings during the Yash Ghai interview. There was no attempt at neutrality’ (Walsh, 2012a).Walsh followed that with another blog entry two days later. ‘Government’s intention was never to prevent public discussion on the draft decree [sic.]’, he wrote. ‘The whole Ghai-police incident and its fallout is unfortunate, inflated, and has been largely misinterpreted, by the media mainly unintentionally, by anti-Government bloggers deliberately’ (Walsh, 2012b). Walsh then speculated that the cause of the seizure was that the regime had lost confidence in the neutrality of the Commission. ‘There were so many stories of Yash Ghai socialising with known Government opponents. . . . I can well understand why

government was concerned: a commission whose key member was no longer neutral was also no longer independent (Walsh, 2013a). The Fiji Sun then ran a front-page story under the screaming headline ‘ACCUSED: Neutrality Of Yash Ghai’s Commission Questioned’ (Bolatiki, 2013). It repeated Walsh’s speculation and outlined in detail the military government’s objections to the Ghai draft, including that it would restore the Great Council of Chiefs, which the regime had earlier abolished (Bolatiki, 2013).Walsh objected in a subsequent blog entry that the newspaper had been selective in reproducing his analysis. ‘The Sun did not misrepresent what I said but it only published half of it – the half sympathetic to Government’ (Walsh, 2013b).

By then the Ghai draft had been published on Fijileaks, a new blog by Victor Lal that specialized in publishing leaked documents à la Wikileaks (Fijileaks, 2012). In addition to restoring the Great Council of Chiefs, it would have repealed or rewritten decrees such as the Media Decree which restricted human rights, provided a role in

Fiji politics for NGOs, and greatly reduced the role of the military. Despite his promise to refrain from commenting on Fiji politics, Davis charged that the Ghai draft was ‘a patently flawed formula’ for achieving democracy that required major revision.

‘If you dissect its provisions, Fiji would wind up with an elite of non-elected representatives and hereditary chiefs whose numbers would far exceed those directly chosen by the people. And what – pray tell – is democratic about that?’ (Davis, 2013c). Davis quoted an anonymous ‘friend’ of Ghai who speculated that his ‘emotions may well have got in the way of his better judgment’. Ghai had a ‘distinctly romantic notion about finally being able to resolve the intractable “Fiji Problem”’, according to this friend, and had come to believe that he could be ‘just as big a saviour as Frank Bainimarama’ (Davis, 2013c). According to Davis’ single anonymous source, Ghai was disappointed when he was initially criticised on anti-government blogs as a stooge of the military government and set about correcting that assumption by courting elements known to oppose the regime. Ghai then went over to their side, according to Davis, deciding to ‘go rogue’ and ‘thumb his nose at due process’ (Davis, 2013c). The Ghai draft was rejected out of hand by the regime, which wrote its own constitution that expressly permitted its restrictive decrees, excluded NGOs from the political process, and provided a continuing political role for the military. It then cancelled the Constituent Assembly that had been planned to ratify it (The Economist, 2013).

3. Participant observation

The author also became the subject of by attacks by pro-regime blogs starting in mid- 2012 while Head of Journalism at the USP in Suva. In a Radio Australia interview with Hill in April of that year, I corroborated his account of dissention remaining within South Pacific media despite a lack of open conflict at the PINA conference. Davis, who along with the AUT’s David Robie had promoted a ‘Pacific media at peace’ meme following the conference, called the interview ‘the biggest crack at revisionism in recent Pacific media history’ (Davis, 2012c). His blog entry was reprinted in the Fiji Sun and on Walsh’s blog, and was the subject of a news story on AUT’s Pacific Scoop (2012). ‘Our recollections of what took place are so vastly at odds that I wonder if we were on the same planet’, he wrote, ‘let alone at the same venue in the same country’ (Davis, 2012c). The conference was boycotted by numerous delegates because PINA decided to hold it in media-managed Fiji. ‘Yes, there were people who stayed away from PINA because it was being held in Fiji’, admitted Davis. ‘Yes, a breakaway organisation, PasiMA, was formed after the debacle in Vanuatu of mainly Polynesian delegates opposed to Fiji’s coup. Yes, one or two delegates . . . made their displeasure felt’.

But for one of the region’s most prominent journalistic educators to seek to exacerbate that division when others are trying to build bridges speaks of a man who simply doesn’t grasp the subtleties and nuances of island relationships (Davis, 2012c). In mid-2012, I started a blog called Fiji MediaWars. ‘It does seem like a bit of double jeopardy’, I blogged about the new TV Decree. ‘Not only are TV stations subject to fines for violating the Code of Ethics and to having their journalists thrown in prison, now they can be put out of business as well’ (Edge, 2012a). That brought a government complaint to USP, as a result of which I put Fiji MediaWars on hiatus for more than two months after posting only a few entries. In September 2012, I organised a two-day symposium at USP on Media and Democracy in the South Pacific. On the first day of the event, Davis posted a blog entry which referred to the event as ‘Edgefest’ and claimed it had caused official consternation across the region. ‘Dr Edge caused intense heartburn right from the start as he set about organising this

conference’, he wrote (Davis, 2012e).

He appears to have set out to be deliberately provocative. In the first draft of the program placed on the USP’s internet website, the list of speakers included two journalists formally banned from Fiji. . . . There was also general astonishment when Dr Edge posted the following [Call for Papers] to the conference comparing certain Pacific countries to the repressive regimes in the Middle East that sparked the ‘Arab Spring’ (Davis, 2012e). Davis claimed that Fiji, Samoa and Tonga had ‘formally complained to the University of the South Pacific. The USP subsequently ordered the posting withdrawn from its website. . . . Unfortunately for the USP, its funding comes from some of the countries Dr Edge appears to be targeting’ (Davis, 2012e). Subsequent to the symposium, I revived Fiji Media Wars to discuss some of the issues raised during the event, including journalistic standards and the problem of self-censorship by Fiji journalists working under the Media Decree (Edge, 2012b). Davis then posted a blog entry that claimed I was clinging to my job by my ‘fingernails’ after ‘official protests and open conflict with other academics’ during the symposium. ‘Grubsheet understands that the USP has triggered formal internal disciplinary proceedings that could lead to the dismissal of the Canadian-born academic. He has evidently been given a formal warning’. It was in an addendum to that blog entry that he admitted what many in the blogosphere had suspected: ‘Graham Davis is now a part-time advisor to Qorvis Communications’ (Davis, 2012f). In November 2012 I posted a blog entry which summarized available information about Qorvis Communication. ‘The more I learn about these rascals’, I wrote, ‘the more I suspect that I have been a victim of their back ops’ (Edge, 2012c).

A subsequent blog entry questioned Walsh’s ethics for accepting a trip to Fiji that was paid for by the regime and designed to provide material for his blog (Edge, 2012d). Another regime complaint to USP demanded that I remove the blog entry about Qorvis. I did so, but I was nonetheless stood down as Head of Journalism by USP

administration. I remained at USP as a senior lecturer, however, and both Davis and Walsh repeatedly demanded that I be dismissed. ‘The School is said to be irrevocably split between the brainwashed first years who worship Dr Edge and senior students who think he is bordering on the certifiable’, wrote Davis, who also complained about a joke I made about Qorvis at the annual USP Journalism awards night. ‘He has brought the USP and its journalism school into disrepute and the sooner he departs these shores the better’ (Davis, 2012g). Walsh took umbrage with my criticism of him for taking a trip to Fiji paid for by the regime. ‘The problems begin with him accepting what’s called a “junket” in the journalism world’, I wrote. ‘As any first-year journalism student knows (mine certainly do), you will not have any credibility if you do not maintain independence from those you write about’ (Edge, 2012d).

Walsh claimed the criticism by myself and other bloggers was unwarranted and suggested that my work permit should be cancelled. ‘It says much for the tolerance of the government and the university that he is still able to publish partisan polemic exercises on his blog’, he wrote. ‘Others have their association with the university terminated, and their work permits cancelled, for less’ (Walsh, 2012c). Davis then leaked email correspondence between USP administrators which showed that my remaining at the university was the subject of disagreement among them. He also renewed his calls for my dismissal as a result of an email that I forwarded to students, which he reprinted and deemed ‘an abuse of office’ on my part. The email was part of a series of satirical missives written by an anonymous author that mocked Davis and Smith Johns and were widely circulated in Fiji. ‘It’s staggering that Dr Edge thinks that it is appropriate for a senior lecturer at USP to pass on this drivel to

those he is meant to be schooling in the serious practice of Pacific journalism’, Davis wrote. ‘In our view, he is abusing his office and it’s high time that the USP brings this continuing farce to a halt’. (Davis, 2012g) As a result of these and other pressures placed on the university, I resigned my appointment just before the end of 2012.

After his August 2013 attack on Radio Australia, Davis blogged infrequently and not always on Fiji in the year leading up to the election, which saw Bainimarama returned in a landslide. In a December 2013 blog entry responding to my noting his months long absence, Davis (2013e) wrote that he had ‘gone quiet primarily because my work is done. . . . Everything that I set out to achieve when I started Grubsheet at the beginning of 2011 and began highlighting the Bainimarama revolution’s achievements has been accomplished’. His absence from the Fiji blogging fray, however, may have instead been the result of a complaint I lodged with SCA CEO Rhys Holleran in mid- 2013 about Davis simultaneously acting as a TV news host and a propagandist for a regional dictator.

Conclusions

Fiji suffered international opprobrium in early 2013 when a video surfaced online showing uniformed officers beating and burning with cigarettes two escaped prisoners, on whom they had also set dogs (Siegel, 2013). While not excusing the abuse, Davis (2013d) claimed it was widely supported in Fiji. ‘These individuals are violent, hardened criminals who had escaped from lawful custody and can hardly have expected to be garlanded when they were eventually tracked down’, he wrote. ‘Many law abiding Fijians actually like being ruled with an iron fist if it means being able to sleep soundly in their beds at night’ (Davis, 2013d). Such abuse was a widespread practice in Fiji, noted Davis. ‘It’s a fair bet that everyone in that clip was raised as a child to expect a “hiding” – the traditional form of discipline in most Fijian homes for even relatively minor infractions. . . .The buturaki – the premeditated beating – has always been the traditional method of enforcing order at village level’ (Davis, 2013d). Political commentary in the U.S. has been likened to a ‘spin cycle’ or ‘echo chamber’ of like-minded pundits repeating and reinforcing pre-determined ‘talking points’ (Kurtz, 1998; Jamieson and Cappella, 2008). This case study shows the same phenomenon imported to Fiji.

The fact that Qorvis Communications was a U.S.-based public relations was likely not coincidental to the Fiji regime adopting an American style system of ‘attack’ commentary. A cycle of attacks on regime critics by regime friendly blogs such as those published by Davis and Walsh was amplified by their frequent reprinting in the pro-regime Fiji Sun, not to mention on other blogs and on several websites associated with the AUT. This not only gave their commentary wider circulation but also greater legitimacy. The online treatment of regime critics by pro government blogs, while typical of Qorvis operations elsewhere in the world, assumed in Fiji a vicious nature not unlike the beatings meted out to pro-democracy advocates and escaped prisoners. This ‘digital buturaki’, as with the real-life beatings, served as a form of social, political, media, and even academic control. It proved a powerful deterrent to anyone who would dare to criticize the regime and a key component of its hegemony. References - (Fijileaks: We have not included the references)

http://www.marcedge.com/buturaki.pdf

Graham Davis: 'Nor does he [Edge] mention the astonishing attack on his credibility by David Robie, the region’s only journalism professor, in his article "The Lies of Marc Edge. 'Counter propagandist’."

Robie

Robie The lies of Marc Edge, 'counter propagandist'

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN once said that “half a truth is often a great lie”, but in the past few weeks the blog Fiji Media Wars has been treating readers to a steady smear campaign. Café Pacific publishes here a statement by journalist and media educator David Robie:

Canadian Marc Edge projects himself as a dispassionate scholar. In fact, he is a polemicist and “counter propagandist” – as he admits proudly on his website – who has regularly used his position at a Pacific university over the past year and since to peddle self-serving disinformation. For those who wondered why I was departing from the usual editorial line of Café Pacific to make a rare personal public condemnation with my “Vendetta journalism” article last Wednesday, the answer is quite simple: To make the truth known.

When I heard Dr Marc Edge’s distortions on his Radio Australia interview late last month blaming Fiji’s military backed regime as the sole cause of his demise at the University of the South Pacific, I decided I could no longer remain silent. In my capacity as a regional journalism educator and journalist, I had the misfortune to cross paths with Marc Edge several times and over varied projects over several months at his university last year. I quickly learned he had his own personal agenda and little of it was to do with the truth or journalism education. In fact, I am now convinced that he never had the welfare of students or the USP journalism programme at heart. He merely wanted to use USP as a pawn in gathering fodder for his proposed “Fiji Media Wars” blog book to trash Fiji and portray himself as a media freedom “hero”. It backfired.

After his misrepresentations and lies in the wake of his disastrous Media and Democracy in the South Pacific conference that he organised last September, I decided to break off any connection with him. Due to his insecurities, his paranoid modus operandi is to run smear attacks against anybody he perceives as an enemy or as competition. Eleven of the last 12 postings (as at January 31) on his blog Fiji Media Wars have been devoted to personal attacks on individuals.

I was particularly disturbed by his repeated misrepresentations of my own views relating to global comparative journalism strategies, such as critical development journalism, deliberative journalism and peace journalism. It is my task with one of the courses I teach at AUT's School of Communication Studies to research and explore comparative journalism models. Clearly, Marc Edge is not even familiar with the literature, let alone to even engage with me on the same page.

He has made false claims about my views and yet never had a professional or theoretical discussion or debate with me. Such a closed mind is dangerous for a university, which should be about ideas and innovation.

For somebody who threatens others with legal action, he is astonishingly reckless with failing to establish facts. Among the many defamatory lies and distortions he has served up about me in his Fiji Media Wars blog in the past few days are:

1. "This assault [my article] was unprovoked by me [Marc Edge]."

FACT: Marc Edge had been harassing me and some of my students for weeks (including one who had lodged a formal complaint with USP) before he was dumped, even falsely accusing me of waging a "vendetta” against him. (We are talking about mature-aged and experienced postgraduate students here with an independent mind of their own).

... David has now enlisted his students in his apparent vendetta against me. [Pacific Media Watch editor] Alex [Perrottet] and Rukhsana Aslam both had full-page op-ed articles that were critical of me [Dr Edge] published in the Fiji Sun ... [Extract from a paranoid letter sent to AUT, Oct 5, 2012]

2. "Make no mistake, Robie is the third leg of the Fiji regime's propaganda stool that is more publicly presented by bloggers [Graham] Davis and [retired USP professor] Crosbie Walsh.

FACT: I have always been an independent journalist and media educator and my mission includes to “balance” the propaganda and disinformation of media people like Marc Edge, who is new to the Pacific, naive and acts if he is an instant expert.

3. Robie's support for the repression the military dictatorship has inflicted on the country's news media is longstanding and central to justifying the current regime's tight control.

FACT: I have been an opponent and critic of Fiji coups and military dictatorship since 1987 – more than two decades before Edge even set foot in Fiji – and my book Blood on their Banner: Nationalist Struggles in the South Pacific was a denunciation of both military repression and ethno-nationalism in Fiji. Unlike Edge, as well as reporting on the earlier coups, I lived in Fiji for five years and experienced the 2000 George Speight coup and political aftermath as an educator at first hand. Also my 2004 book Mekim Nius: South Pacific media, politics and education condemned political interference in education and defended academic freedom.

David Robie's 2004 book Mekim Nius

on Fiji and Pacific media and politics.

4. In fact, his 2001 "Coup coup land" theory was the very justification for the draconian 2010 Media Decreethat provides fines and even prison sentences for journalists.

FACT: This article in Asia Pacific Media Educator was not a “theory”, it was a widely referenced and cited peer-reviewed preliminary exploratory paper about the George Speight coup and media coverage. It has led to many independent serious academic studies at different universities since then that have borne out my findings. In addition, I was among some 26 individuals and organisations that provided submissions to the independent and self-regulatory Fiji Media Council Review in 2009. Nevertheless, the regime ignored the constructive Review recommendations and imposed its own repressive law. I have never had anything to do with the draconian decree but I have written many papers condemning and critiquing it. The Pacific Media Watchproject that I was co-founder of in 1996 has been dedicated to media freedom in Fiji and the region.

5. "Robie has been pushing government-friendly alternatives to press freedom in Fiji and elsewhere in the South Pacific, namely "development" journalism, which sees media working in partnership with government to encourage development, and "peace" journalism, which envisions media proactively proposing solutions to conflict in society rather than merely reporting events neutrally.

FACT: As part of my “comparative journalism studies” course, I have explored varying models of journalism and none of them are “government friendly alternatives”. There are several different notions of “development journalism” and Marc Edge seems to have no familiarity with this complexity – he constantly trots out a discredited Western-defined version. I do not, and have never, advocated “working in partnership” with governments, except for collaboration in defined issues such as climate change, and only in a democratic framework devoid of censorship or media persecution. Instead, I have argued for critical development journalism (a style of robust investigative journalism seeking solutions) and deliberative journalism (a more democratic form of journalism). A quick excerpt from this fullpage article of mine in The Fiji Times on September 13:

Deliberative journalism involves empowerment, often a subversive concept in conservative societies. It involves providing information that enables people to make choices for change.

Deliberative models include notions such as public journalism, critical development journalism, peace journalism and even human rights journalism.

Development journalism in a nutshell is about going beyond the “who, what, when, where” of basic inverted pyramid journalism; it is usually more concerned with the “how, why” and “what now” questions addressed by journalists. Some simply describe it as “good journalism” with greater context.

The notion of peace journalism is actually a very positive approach, especially in countries where social and ethnic conflict has been long-standing and is a form of journalism that addresses the root cause of the problems, not just a surface compromise. Leading global journalists and academics advocating this approach include Associate Professor Jake Lynch, director of Sydney University's Centre for Peace Studies, who was a keynote speaker at a conference at USP about the strategy.

None of these notions are necessarily substitutes for “watchdog” journalism holding powerful institutions to account, they are additional tools well-suited to the complexities of the times and communities we live in. And media corporations and companies are themselves among these “powerful institutions” that need to be held to account. However, the failures of watchdog journalism itself and media credibility are under serious scrutiny as part of the global journalism crisis – the News of the World phone-hacking scandal backlash is an example of this.

Part of the problem in Fiji is that there is little “neutral” journalism in the country. Six years of censorship and self-censorship have seen to that. But much of the reporting about Fiji in Australia and NZ is also biased. It often takes independent external media organisations such as Al Jazeera to provide a better balance.

6. "PMC is obviously pro-regime … "

FACT: The Pacific Media Centre is an independent research, publication and media resource centre at AUT University and governed by an advisory board and is part of the Communication Studies school. It does not have any political line, but seeks to publish a wider range of articles about Asia-Pacific media and socio-political issues than is usually available in New Zealand-based media. Marc Edge has never visited the PMC, or even this university for that matter, and his ignorance about PMC is astounding for an academic.

The objectives of the PMC can be viewed here in this 5min video on YouTube. The PMC’s mission is also on public record here.

Ironically, while Marc Edge falsely accuses me of support for the Fiji regime's media policy and repression it is actually he who is “collaborating” with the Media Decree; he currently has a complaint against a Fiji media organisation before the Media Tribunal – using the very instruments of media persecution imposed by the regime. Hypocrisy in other words.

In the words of one of Marc Edge’s former students, one of the many victimised during his USP “dictatorship” era, Magalie Tingal, from Radio Djiido in New Caledonia, it is time for him to move on and get a “get a real job” and let us in the Pacific get on with ours in peace.

David Robie is author of Mekim Nius: South Pacific media, politics and education (USP Book Centre, 2004) and was the head of journalism at the Universities of Papua New Guinea and the South Pacific (Fiji) for a decade.