"When will it be our turn to TASTE POWER?" - Dictator Bainimarama's election win will encourage serving military officers to overthrow him - that is another unintended result for VOTING for him and his Fiji First (Theft) Party - so Coup Culture |

Fijileaks Opinion Columnist

1. The Voter Turnout Percentage (2014 election) is unusual because no party paid transport buses were allowed on polling day. If you have massive free public transport efforts put in by many different parties over a week, and compare that to a One-Day Vote where people have to get themselves to their nearest polling station, then its very hard to believe that the 2nd could produce a better turnout than the first.

2. The changing vote percentages throughout the vote count were also unusual. Not the fact that they changed. It was the way they changed.

Normally any vote - particularly a one-day vote inside a 3-day campaigning blackout - will just be a "snap-shot" of the "Will of the People". In other words, the result of the vote is "set" at the end of the voting period, but it is just not known yet. What makes that result known is of course the final count.

However before that final figure arrives, the progressive count will give some approximation of what the final result will be. That is why many good pollsters can accurately predict a final election result after just 5% of the vote count is known. Because you should be able to see the trends, and then just accurately extrapolate those over the whole vote. Which is what they do. This happens all over the democratic world because statistical principles work all over the entire world.

Most importantly, these principles work because they function in the "closed system" of the end of the vote. In other words, whatever influences that existed at the time of the vote or campaign blackout, are set in stone by the time the vote starts. So they can be "detected" early in the vote count, as well as late in it.

Together, the "closed influences" and the statistical trends mean that the initial count trends will approach the final count results, as a "decelerating" asymptote. Or as a decreasing oscillation. Around or towards the final vote percentage figure, I mean.

So in statistical practice, if one party say got 55% of the vote as its "set" result", that might show up as 49% or 60% in the early polling. But that initial figure will "refine" itself towards, or approach, the "set" result as the count proceeds, in a decelerating "curve". And because statistical forecasting techniques will be in an environment of "closed voting influences", that will allow pollsters to accurately predict past those early approximation "errors", to confidently estimate the final figure.

The key point being as the count proceeds, it becomes more precise. In other words, it becomes a more accurate reflection of the "final result". Which is why the progressive voting percentage behaves like a "decelerating asymptote", or a decreasing oscillation. Because it too, is "getting more accurate". And as it does, the changes in the percentage get smaller because of that increasing accuracy.

So whilst a winning party can be expected to “pull away” from the others in terms of total votes, that will not happen with their voting percentage, which will become increasingly stable and predictable as the count proceeds.

Consider this in the light of the Fiji Election vote count where it seems like the votes for the respective parties appeared to "accelerate" away from their initial polling percentages.

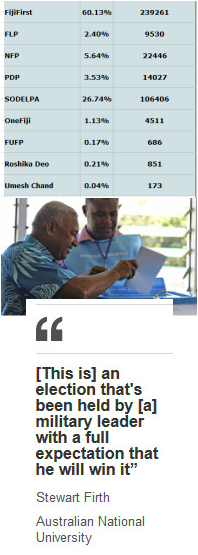

FFP was perceptibly below 50% at the start, while SODELPA was easily above 40%. But by the end, FFP had accelerated to 60% whilst SODELPA accelerated downwards below 30%.

Such large swings themselves are not unheard of in genuinely fair votes. But the way the voting percentages changed - i.e. they continued at a constant clip towards those marks around or from the middle third of the vote count, is odd from a statistical point of view. If the count was truly a "closed system" that is.

In other words, if the vote outcome was truly "set in stone" at the end of the voting day, and before the counting started, the initial percentages should have started off much nearer to the final outcomes. And the statistical approach to those outcomes as the count proceeded, should have been decelerating. Not continually increasing at a constant rate through the last 2/3rds of the count.

This suggests that the system was not closed, and that “new influences” were being introduced into it which did not allow the voting percentages to stabilise. It would be interesting to see if the same “voting percentage instability” pattern held with the smaller parties vote counts, too. Although I cannot state from memory if it did.

Of course, shift in voting percentages could all come down to the rural-urban shift in the voting count from the pre-polling and postal votes, over to the urban centres. But SODELPA was stronger in the urban areas as that is where they concentrated their pocket meeting campaigning. So their apparent drop in support in the urban count was counter-intuitive. Unless it could be explained by all the soldiers marching around Fiji in full uniform on the weekend before the vote.

3. These voting patterns were also highly odd in terms of the party campaigning experience on the ground - at least in the Lami area. Towards the end of the campaign period, FFP could barely get anyone to even attend their pocket meetings in and around Lami. And when they (FFP) had their big campaign meetings in Suva and Nausori, they had to do it as part of a “Family Fun Day” outreach with plenty of free giveaways to attract attendance. Even then, they didn’t get notably more attendants than SODELPA's purely political “big gatherings”.

4. In previous elections, we always had voter exit polls from which to gauge our party performance on election day. And more importantly, to be able to compare with the final vote counts when these came out. Exit polls were not available this time because of regime election decree rules. So the next best thing is just straw polls from peoples’ personal experiences. As one analyst put it: "I have never been part of an election previously where nobody I knew personally was going to vote for a party, and that party did well. Even in the past, although I thought my party was going to do well, I still personally knew people who I knew were going to vote for one of our opponents. This is the first time ever in my experience where nobody I knew personally was going to vote for the eventual winner, whilst almost everyone I don’t know must have voted for them. Surreal much."

5. The voting patterns were also highly discordant with FFP’s candidate-fielding experience. Just a couple of weeks before nominations closed, Bainimarama had to order his Cabinet and his district officers to stand for FFP. The clear implication is that they had not attracted any (or enough) high quality candidates from their public canvassing process, themselves. So to go from struggling to even field competent candidates, to “romping in” an election victory with 60% of the public vote, is a huge turnaround in fortunes which is very difficult to explain. Especially when considered in the light of the “odd” changes in voting percentages over the counting stages. And double-especially when only a relatively small crowd is celebrating the win at the FFP “victory tent”. I tell you, if my party won, I would absolutely have taken some time off work to at least go down and visit them.

6. By some counts, voter turnout yesterday was 97%+. By other counts, there were actually more ballots counted than registered voters.

Obviously the 2nd scenario is a big problem. But even the first is not without issues. The first of which is that all around the world in democratic experience, high turnouts have always been associated with either: 1. A close race, or 2. A big vote for "Change" (as in, change of government).

Fiji must be a very special case though, because our big turnout produced neither of those two.