Recently, some Fiji academics organized a conference commemorating the arrival of the last Indian indentured laborers ship to Fiji and asked me to contribute. I thought that I would republish my 1979 article on CSR’s exploitation of indentured laborers and small cane farmers, but with a new Preface to emphasize that Fiji has moved on, that there are other racisms in Fiji that need to be tackled other than the colonial white racism, that our own local companies are as bad, if not worse local exploiters of workers today than the old colonial white companies of CSR, Carpenters and Burns Philp, and that we should not forget the many decent white residents of Fiji (including British civil servants) who lived exemplary professional lives, free of corruption. The girmitiya conference took place a few weeks ago. The book was not able to be launched at the conference but is available at the USP Book Centre.

A debate taking place currently in Fijileaks reminds us also that there were far worse systems of real slavery of Africans and others taking place a couple of hundred years ago, and that in Fiji there was also horrible racism some continuing today against indigenous Fijians and those “blackbirded” (enslaved) laborers from Vanuatu and Solomon Islands, whose descendants still suffer in Fiji today, very much neglected. The new Preface from the republished monograph may have some relevance to this debate in Fijileaks.

From my Preface (2017): why republish?This monograph is based on a long article originally published in the Journal of Pacific Studies in 1979, to commemorate the centenary of the arrival of the indentured labourers (girmitiya) to Fiji. There are several reasons for republishing this article. First, the old JPS editions and the article have not been easily accessible to students and researchers and seem to have “fallen off the radar” of subsequent researchers. This publication (as hard copy and eBook) will hopefully remedy that.

Second, leading Fiji academics are holding a conference (22 to 24 March 2017) to commemorate the date of arrival of the last ship with the Indian labourers. I am grateful to the conference organizers (Dr Ganesh Chand, Professor Biman Prasad and Dr Rajni Chand) for agreeing to launch this monograph at the conference.

Third, despite the several good policies brought in by the Bainimarama Government (such as in freeing up preschools and education in general), their policies on the struggling sugar industry leave much to be desired and hark back to the colonial past.

Fourth, a re-examination of the colonial past ought to make us think not just of the racism and economic exploitation by the whites in colonial Fiji, corporate entities or governments, but also about our internal racisms and economic exploitation of our workers and farmers by our own capitalists.

A new girmit era for the sugar industry?

This old JPS article has recently acquired a historical significance. Tactics used by the colonial government and CSR (as indicated in this monograph) are being revisited by post-independence governments and Fiji Sugar Corporation (the successor of CSR). Stakeholders in the sugar industry today need to learn from history if they are to better understand their current predicament and not repeat mistakes.

Recently, the Bainimarama Government pushed through without consultation with the cane farmers, the 2015 Sugar Industry (Amendment) Bill. Hon. Professor Biman Prasad (Leader of the National Federation Party (NFP) in parliament condemned the Bill which effectively ended democracy in the Sugar Cane Growers Council probably to allow government to dictate changes in the Master Award. Professor Prasad protested that “the farmers, their families, the cane cutters, lorry operators, lorry drivers, labourers and farm hands have every right to feel demoralised. They are entitled to the same transparency and accountability the Government repeatedly promises to Fiji’s people. But now their Council will be completely undemocratic and unrepresentative, selected for their loyalty to the Government and not to the farmers.”

Another NFP MP at the time, Roko Tupou Draunidalo pointed out that the entire sugar industry, including the farmers, the mills and fertilizer company, was controlled by the Bainimarama Government dictatorship, with cane growers being reduced to “mere pawns, battered from pillar to post and asked to pay through direct and indirect taxes again through the administration of an organisation that they have no say or control over. This is reminiscent of the days of CSR when the master imposed his will on helpless growers. One would have thought, Madam Speaker, that the Girmit ended 99 years ago, but this Bill is enslaving growers into Girmit once again.”

The NFP warned that history would judge the Bainimarama Government harshly. But I suggest that it is for farmers to first know the history of the their forefathers in the girmit era, part of which is given in this monograph.

Unfortunately, while the current government’s political policies may be similar to those of the colonial government and CSR, the horrible difference is that the sugar industry has virtually collapsed under the current dictatorship, without the economic productivity of the colonial era. Since the Bainimarama coup of 2006, sugar cane and sugar production had virtually halved, while government Ministers and Permanent Secretaries for the sugar industry, and government appointed CEOs of FSC have issued endless optimistic forecasts for the last ten years, until quietly departing.

Ignoring our internal racisms

The reference to “white” racism in the title of the original JPS article reflects the pre-occupation that Indo-Fijian academics in that era (myself included) had with the racism by the colonial state and whites in Fiji against Indo-Fijians. Thus most accounts of the colonial sugar industry (this monograph included) focused on the racist exploitation of the girmitiya by the white owned CSR with the assistance of the white dominated colonial government.

But my experience in the last twenty five years suggests that neither racism nor economic exploitation of farmers and workers is the preserve of whites. Yet it is extremely odd that in the Indo-Fijian academic discourse, which in recent years have also been criticizing, with much justification, the racism by indigenous Fijian ethno-nationalists against Indo-Fijians during the coups of 1987 and 2000, there is little mention of the many internal Indo-Fijian racisms between Gujarati, Hindustani, South Indian, North Indian, upper and lower castes, and the many other sub-groups.

I have from childhood been aware of the Gujarati community being racist towards Hindustani derogatively calling them kakka and discouraging marriages between their children. But there also has been the converse, with Hindustani being racist towards Gujarati (derogatively calling them Bombaiya khijdri) although I never expected it would to be directed towards me personally, given my multiracial life and work.

But during the 1999 elections in which I was seeking re-election to the Fiji Parliament, some Hindustani political opponents, purely to obtain Hindustani votes, accused me of being a Gujarati economist “in the pockets” of Gujarati businessmen, who were allegedly exploiting the descendants of the girmitiya. These politicians well knew that I had been a founding member of the Fiji Labour Party and as an economist had supported for thirty years all working people of Fiji, including the descendants of girmitiya. Certainly Gujarati employers did not see me as a friend or even “in their pockets”. Some political opponents would have known of my 1979 JPS article (reprinted here) and some former USP students would have known of the even earlier 1974 UNISPAC article (included in this monograph as an Annex) on the plight of Koronubu and Field 40 cane farmers facing expiring land leases.

Then, when I had thought that the anti-Gujarati sentiments were a thing of the past, I had the shock of receiving at the end of 2014, a vicious email from an Indo-Fijian Australian resident (a graduate of USP) who castigated me that I as a Gujarati had no right to be making comments on Fiji, and that I should ‘return to India where I belonged’.

This racism against Gujarati, not isolated by any means, may have been driven by anger at the enormous influence that a few Gujarati businesses have in the Fiji economy today. But it lumps together all Gujarati, capitalists, workers and professionals, including academics like me who have fought over the years for the livelihoods of the girmitiya and their descendants. It is paradoxical that some of the anti-Gujarati sentiments are coming from passionate supporters of Bainimarama who is extremely close to the Gujarati businessmen and for instance, accedes to their pressure to postpone Wages Councils Orders. It goes without saying, of course, that Gujarati businessmen, like businessmen of all ethnicities, also provide employment and incomes in Fiji.

It is also unfortunate that some Hindustani writers on the history of Indo-Fijians have largely ignored, deliberately or otherwise, the work of Fiji’s Gujarati academics including Dr Padma Narsey Lal who has written volumes on the problems of the sugar industry (including Ganna) as well as that of her husband, historian Professor Brij Lal, both being thanked for their services by being banned from Fiji by the Bainimarama Government.

It is worrying that there have been some politicians who have used the sufferings of the original girmitiya to drive wedges between the descendants of the girmitiya and the descendants of other ethnic Indo-Fijians like Gujarati. I can personally attest that the children of working class Gujarati, like my family, have had very similar upbringings and hardships to the descendants of girmitiya. One might also say the same of many working class or rural indigenous Fijians, Chinese, and kailoma.

It is not healthy that academics today generally ignore other non-white racisms in Fiji: Eastern Fijians against the Colo hill tribes; “part-Europeans” (now “part-Fijians”) against other non-white Fijians; while wild generalizations are also made against the Muslims and Chinese. It is a continuing national tragedy that ethnic tensions are never far from the surface, despite the Bainimarama Government’s frequent message that “we are all Fijians”. One hopes that this is not just a political illusion to be shattered in the future, as it has been so many times before.

While I would not wish to underplay the force of white racism in colonial Fiji, nevertheless there also were many whites in colonial Fiji, including colonial civil servants and others, who were decent multiracial members of Fiji society, and who ought not to be tarred by the same brush as might even be inferred by the title of my 1979 article. While I have been tempted for all the above reasons, to change the title from “white racism” to “racism”, I have refrained from doing so, as the old cumbersome title also reflects the Indo-Fijian academics’ preoccupation with racism by whites against non-whites, while refraining from turning their critical spotlight on their own internal racisms.

Worse non-white exploiters today

This article was written in 1979, when USP academics (like myself, Brij Lal, Jai Narayan, Vijay Naidu, Raymond Pillay, Satendra Nandan, Subramani and Simione Durutalo, were preoccupied with foreign (Australian, NZ and British colonial government) exploitation of the Fiji economy and people. It is paradoxical therefore that in the last forty years of politically independent Fiji, the local non-white capitalists have shown themselves to be as, if not more rapacious than the CSR criticized in this article, or Australian giants Burns Philp and Carpenters criticized in another monograph I was involved in more some forty four years ago.

Indeed, as many of my three decades of writings have tried to explain, our own elected governments have been even more extreme in their attempt to control workers and farmers. It is ironic that today’s employees of white employers and companies generally have better wages and working conditions than the employees with non-white employers, despite all the best efforts of Wages Councils and dedicated clerics like Father Kevin Barr, who I have also assisted over the years. Neo-colonial exploitation is alive and well in Fiji, practised by our own people and no longer the sole domain of foreigners.

I suggest that researchers (and those at the 2017 girmitiya conference) might wish to ponder on my optimistic concluding paragraph of the 1979 article (p. 65 in this monograph)

“Lastly, FSC has dispelled the popular myth that large enterprises should be the domain of private capitalists only. With most of the staff localised and FSC in fact achieving more in production than was ever previously achieved, local expertise can be and has been created to run any large or small enterprises in our economy. The myth that foreign capital and expertise is a necessary component of development should be put to rest once and for all.”

Where did we go wrong? I suspect that a large part of the answer will be the 1987 coup led by Rabuka (and not so shadowy figures behind him), the 2000 coup (instigated by shadowy figures not yet identified) both leading to a massive loss of skilled, technical and professional people, without whom FSC has struggled. The Fiji Bureau of Statistics data indicates that the emigrants are not just Indo-Fijian but of all ethnic groups, including more and more indigenous Fijians in recent years.

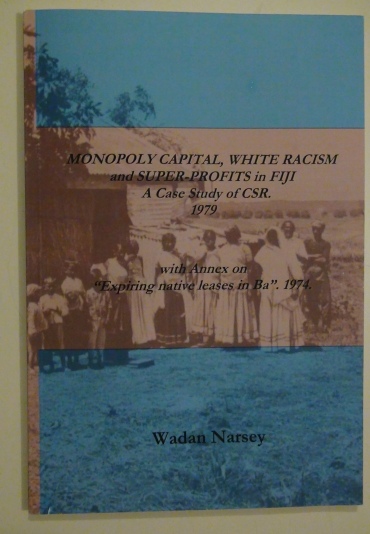

I am grateful to the Fiji Museum (William Copeland) for the indenture period pictures which were not in the original JPS article.

Professor Wadan Narsey

Melbourne

2017