"Rabuka introduced the Sunday Observance Decree after the second coup [in 1987] to prohibit work, trade and social activities on Sundays, but not to promote religious activities as much as to repress Indians [Indo-Fijians]"

Fijileaks: As we have argued before, the former NFP leader Jai Ram Reddy sold the Indo-Fijians and other 1987 coup opponents for the sake of sharing power with coupist Rabuka. The famous handshake with the "Devil" after forming a political alliance to fight the 1999 general election was a sign of political immaturity and crass greed on the part of the NFP. Reddy had signed a pact to become Rabuka's Deputy Prime Minister if SVT-NFP won that general election. In other words, to remain second class citizen in Fiji. Now, others are rushing to shake hands and form political alliances with the Father of Coups in Fiji. The new NFP leader Professor Biman Prasad will be putting his head on the ballot box for a CHOP if he makes the same mistake as his predecessor REDDY by forming a coalition with SODELPA under Rabuka's leadership.

Victor Lal: "Having studied, analysed, and commented on Fijian politics for forty years, I fear for FIJI, especially with Rabuka-Niko Nawaikula, Ratu Naiqama Lalabalavu and Adi Litia Qionibaravi driving SODELPA agenda...with Alipate Qetaki popping up as possible SODELPA candidate with Rabuka"

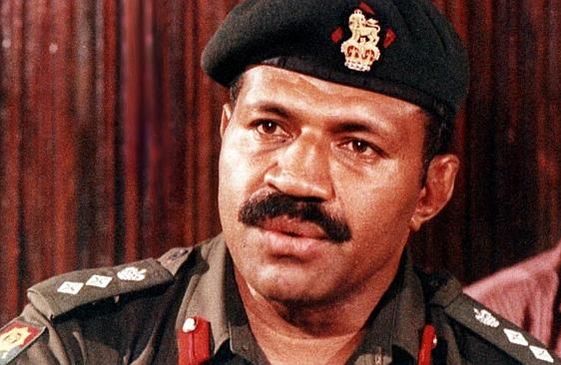

Cry the Beloved Country if we allow coupist Sitiveni Rabuka back into power. Lest we forget, he was sent into political wilderness after losing the 1999 general election, and his CV reeks of opportunism every time Fiji has plunged into crisis. If the SODELPA rank and file want to win the election, they must demand the sacking of Rabuka as their leader, and Ro Teimumu Kepa should be re-appointed to lead the party into election - if she declines, someone not tainted with coups should be selected to replace coupist SITIVENI RABUKA. Many have forgotten “Operation Sunrise: The Rabuka Story”, a film which flattered Rabuka and his coups; when seven women protested outside the premiere of Rabuka’s film on 20 April 1988, they were arrested and detained for several hours. A student seen taking notes during the film was similarly detained. GOD HELP FIJI! He is hiding behind IMMUNITY he granted himself for his treason and subsequent crimes. There is political room for a truly multi-racial political party to fight next election! We predict a RABUKA victory at the polls will result in

5th COUP in Fiji. The military will not allow the repeat of 1987 with SODELPA wanting to bring back Chiefs, Church, Culture and Corruption under Rabuka's leadership

[Sitiveni] Rabuka introduced the Sunday Observance Decree after the second coup [in 1987] to prohibit work, trade and social activities on Sundays, but not to promote religious activities as much as to repress Indians. The Fiji Council of Churches believed the Decree crossed “the limits of state authority”.

To legislate for the worship of Christ the Lord is to go against the whole spirit of the Gospel which sets people free from the bondage of the law. Worship cannot be enforced by the threat of punishment and force of arms.

The Decree stayed in force until October 1995; its retention for a long time a litmus test of Rabuka’s authority over the interim government and a means by which Rabuka garnered support from Methodist fundamentalists, his new storm troopers to replace the faded Taukei Movement.

Many Taukeists wanted Fiji declared a Christian state; few admitted that their goal was simply to alienate Indians further. Rabuka expressed a desire to convert Indians to Christianity on one occasion but it was more common for radicals to declare the presence of non Christian temples and mosques an affront to their religion.

Not surprisingly many temples and mosques were vandalized or burnt, among them a temple in Nadi in June 1988, at Kinoya in September 1989, and at Raiwaqa and Vatuwaqa in Suva during September 1991. At the Vatuwaqa temple, a Fijian assaulted the chief priest for worshipping idols. Arya Samaj, chairwoman of FYSL’s Cultural Committee, claimed that “such actions are part of the overall efforts to take away the willingness to struggle from Fiji Indians”.

The authorities often encouraged anti Hindu sentiment by claiming that temples were used illegally for political purposes. Kubuabola criticized Bavadra and Reddy for speaking at a Ba Diwali celebration in November 1988. After GARD members burnt the [1990 racist] Constitution at the Howell St temple, the Sangam denied approving the protest and quickly issued a statement that the temple could not to be used for political purposes. Armed troops had raided it once before in August 1988 on the pretext that political activities were being conducted within its walls.

On 15 October 1989 in Lautoka, one week after Indian organizations met in Lautoka to discuss the future of their people and called upon Indians to be “united and firm in the struggle for honour, dignity and equality”, 17 Fijians dressed in their Sunday clothes and clutching Bibles sang hymns while they firebombed temples and mosques. Temple authorities complained that police responses had been very slow, and Lautoka shut down for a day of protest on 19 October.

When the Wesley Church was firebombed in apparent retaliation on 16 October, members of cabinet went into damage control and visited Lautoka during the day of protest. Eighteen Fijians were eventually charged with the offences. They were all members of the Lautoka Methodist Youth Fellowship, an organization associated with Rev. Manasa Lasaro, the Taukeist who for much of 1989 pursued his own coup within the Methodist church.

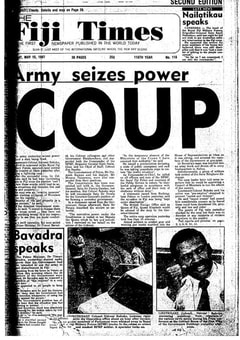

Since 1987 a close relationship existed between Rabuka and fundamentalist Christians. His biographer, Stan Ritova, believed Rabuka “owed the success of his coups partly to the support of the anti Indian Fijian wing of the [Methodist] Church”. Rabuka, a Methodist lay preacher, claimed God told him to undertake the coups for the benefit of Fijians. His old friend, Rev. Tomasi Raikivi, hosted the initial Taukei meeting with Rabuka on the Easter Monday following the Coalition’s victory in April 1987. Then Secretary of the Bible Society, the Baptist Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, acted as go between. In his offices the final decision to launch the first coup was taken.

Since the vast majority of Christians in Fiji are Fijians, Christianity is often regarded as part of Fijian culture. According to Rev Akuila Yabaki, the former Methodist Communications Secretary, “ministers have very powerful positions in Fijian societies ...[reaching] down to the village”. Both factors have assisted to make Christianity part of the vocabulary of Fijian nationalism. Taukeists successfully

managed to articulate their demands for adherence to Christian principles and practices such as the Sunday ban with claims for Fijian political dominance. Thus they succeeded in turning these two demands into two inseparable issues ...reflecting the way in which Methodism in Fiji had been absorbed into Fijian consciousness.

Hence the Taukeist demand that Fiji become a Christian republic represented, according to Yabaki, the desire for “Fijian domination in all aspects”. They did not regard Christianity as a consequence of colonialism or as a form of neocolonialism like democracy. The Sunday Observance Decree, became a demonstration of difference around which Fijians could rally.

Rabuka later declared that the Sunday Ban had been introduced only as an extension of the curfew, as a security measure. In the sense that it existed to harass opponents of the coups, in particular Indians, it was certainly “a strategic move rather than a religious one”. Ironically it became very unpopular among many Fijians who had to walk long distances to church in the absence of public transport.

At one stage Rabuka argued that the ban was designed to stop young Fijians wandering aimlessly around, although how a one day ban resolved the problem for the rest of the week was never explained.

Nonetheless, having gained the symbolic Sunday ban, the faithful had ever to be on the alert to protect it. That necessitated Fijian unity within the Methodist Church as much as in the wider political sphere. No compromise was possible. Consequently, when the interim government relaxed the Sunday Ban in May 1988 to enable farm work and picnics, Methodists held a vigorous protest rally in Suva.

Not all Methodists agreed with the fundamentalist line. Yabaki likened it to fascism.

Every time we shrug when we hear of another midnight raid, the cries of terrorized women and children, then somewhere in Fiji another potential [Klaus] Barbie [the Nazi butcher of Lyon then on trial in France] is getting a start in life.

Indeed, immediately after the first coup the Methodist Church and members of the Council of Churches had urged Fiji’s peoples to work together. But with the exception of Yabaki, former Methodist president Rev. Daniel Mustapha and Rev. John Garrett, the clergy remained silent. Because the Methodist church was not organizationally or ideologically multiracial, it proved an excellent forum for the promotion of Taukeist principles.

General Secretary Manasa Lasaro lay behind this push. A 45 year old former policeman from Bua in Vanua Levu who had studied at the Welsh University of Swansea and at Reading University in England, Lasaro directed the Church’s youth training centre set up by the West German Hans Seidel Foundation. After the coups, he and Raikivi, Rev. Ratu Isireli Caucau (an important Bauan chief), and the Church’s administrative secretary Ratu Emosi Vuakatagane vowed to use the Church’s resources to pursue the goals of the coups and what they presumed were also the goals of all Fijian peoples.

In June 1987 Lasaro organized Fijians in Vanua Levu to cut cane during the cane harvest boycott. “A lot of things have been said about multiracialism”, Lasaro claimed, “but equally important to this framework is that the different races have got to preserve their identity as a people, in their own race”.

But the Methodist president, Rev. Josateki Koroi, objected. Lasaro claimed Koroi obstructed his day to day running of the church, and tension between the two mounted. When in October 1988 the interim government relaxed further the unpopular Sunday ban by permitting limited bus and taxi services, Lasaro reacted instantly. He declared his preparedness to die to preserve the Sunday Observance Decree. Together with Butadroka, Lasaro organized 70 road blocks around Suva on 18 December, paralysing the city and greatly embarrassing the interim government. An appalled Mara argued that their action “touched on raw and sensitive nerves in a community which had already undergone the trauma of two military takeovers”. He dated the decline in his own health from this point.

The roadblocks were lifted, but only after Rabuka intervened. He met the protestors the next day and reportedly told them that he would resume control of government if it failed to act against commerce and recreation on Sundays. But the Methodists were no longer satisfied with his assurances. They wanted the Decree strengthened to include hotels, airports, and all use of private vehicles.

“So much has been taken away from us”, declared Lasaro, “and we are now left only with our faith which we will fight to the death to keep”. Rabuka had no choice but to tow the cabinet line. “We are one nation”, he responded, “...do not let us impose our views and beliefs on other people”.

Consequently taxis could operate on Sundays but they had to be ordered through police stations. In reality few taxis were on the road, much to the disgust of Christmas and New Year revellers.

Koroi suspended Lasaro. “The Sunday Decree is not Methodist and is not Christian and is not scripturally sound”, he declared. To Lasaro this was irrelevant and fresh roadblocks appeared on Christmas Day. Police arrested some 150 people, including Lasaro. They were charged with illegal demonstration, and conditionally discharged. Lasaro could count on considerable Church support. Nineteen of the Methodist’s 26 divisional superintendents sought his reinstatement.

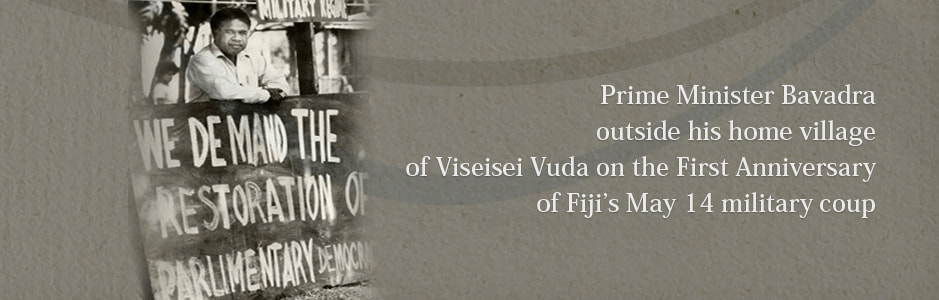

Western Viti Levu and Lau did not. When Koroi refused to budge, the rebels met on 3 February 1989 and suspended the Church’s constitution. They barred Koroi from his office, declared his position vacant, and replaced him with Lasaro supporter - Caucau. Koroi believed he had the law on his side. He did, but then so had Bavadra in 1987.

On three occasions Koroi had the High Court declare that he and his standing committee were the legal administrators of the Church. Lasaro lawyer and Taukeist, Kelemedi Bulewa, scoffed at the declarations.

The suspension of Rev. Lasaro was unconstitutional just like the coup which was considered illegal. We should not ask now whether the actions taken have been unconstitutional because any constitution can be amended or added to if there is a need.

Sir Timoci Tuivaga disagreed. “I think it is right to state...that majority wishes or support alone without constitutional or legal backing”, the Chief Justice noted, “is not enough to render unlawful actions lawful”. But twice Lasaro and his supporters ignored Tuivaga’s order. Lasaro regarded such orders as a stepping stone for the Coalition to take the government to court, seeking a declaration that it was the legal government of the day.

“The ‘coup’ in the Church”, said a frustrated Chief Justice, “is subject to municipal law, that is the ordinary law of the land and must answer to it”. But the minister responsible for enforcing that law was none other than Rabuka, and he had other plans. Together with Mara and Ganilau, he visited Lasaro to receive a petition protesting the Court’s ruling and demanding a widening of the Sunday Observance Decree.

Lasaro continued to ban Koroi from his Epworth House office, claiming that he violated the Decree on his farm and consorted with dissidents. But protests were not enough to save Lasaro from a third court order on 18 April and a consequent charge of contempt of court for which he and Vuakatagane received suspended sentences. Both apologized to the High Court, but not to Koroi, who returned to his office and petty harassment.

Church officials allegedly also plotted their revenge on Koroi with a plan to use ex prisoners to rape Koroi’s wife in front of her husband at their Deuba house. A social worker in charge of security at Epworth House had the task of executing the plan, but he and his men refused to carry it through. On the appointed day they told the officials that the Korois were not at home. In May, the Church’s education secretary, Epeli Tagi, resigned following physical attacks.

Koroi was really now of secondary importance to Lasaro since his term as president expired at the end of the year and the Church’s August conference would appoint a successor. Obviously attendance at the conference was vital to sustain the Taukeist push in the Church. But Lasaro nearly missed it. During July Labasa Methodists protested the harvesting and milling of cane on Sundays. Lasaro happened to be in Labasa on youth training business and his relatives asked him to participate. Fifty seven people were jailed as a consequence of the protest, Lasaro for 6 months.

Rabuka suddenly flew to Labasa and visited Lasaro at Vaturekuka Prison.

Two days later on 12 August he released all 57 prisoners on compulsory supervision orders.

At the Church conference Lasaro apologized for the divisions he created and the conference renewed his position as general secretary. Caucau became the new president. The Methodist coup had been legitimized. However, there were warnings of problems ahead. On the very last day of the Conference, questions were asked of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation’s $1.2 million three year deal for the Youth Fellowship task force at Davuilevu, allegedly negotiated outside of the Church’s main decision making bodies. “It is sad that money has become the law of the Church”, lamented Koroi.

Competition between Rabuka and Mara formed the political backdrop for the whole Church saga, almost a replica of 1987 in miniature. 1988 had seen the arms fiasco and the short lived ISD, 1989 a secret military proposal to resume control at the end of the interim government’s term. In neither year, nor of course in subsequent years of the interim government, were human rights of paramount concern to the authorities.

Much later, as the harshness of these years faded in people’s memories, Jai Ram Reddy praised Fiji’s citizens for their resilience.

The fact that we have not descended into the kind of violence and disorder that some other countries have had to endure in the name of race and religion is also our good fortune, although we ourselves have been very close to the precipice.

Mara concurred. “I think all the citizens of Fiji can feel pride in the way Fiji came through the ordeal”, he told Ganilau in mid 1992. “We came close to the abyss, but we did not fall”.

But there had been incredible pain.

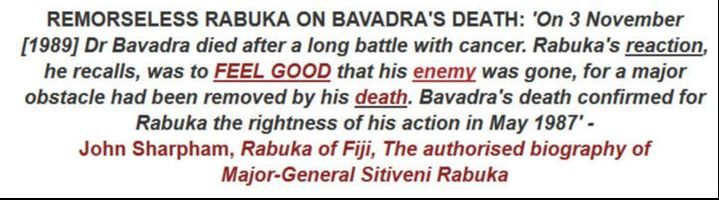

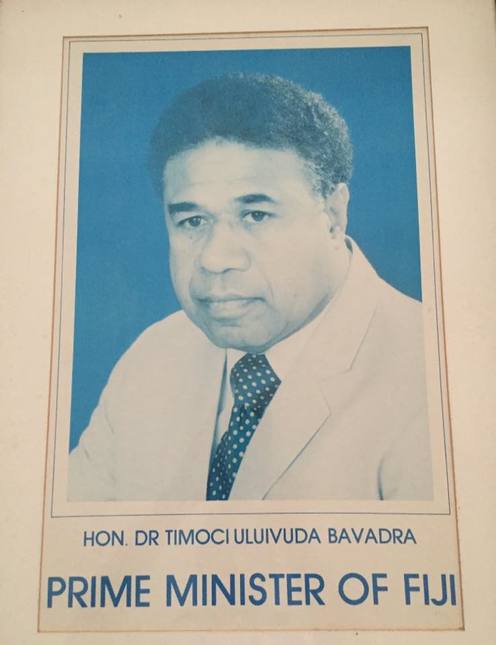

Consequently when Dr Timoci Bavadra succumbed to cancer after less than a year of treatment, the nation mourned as it had never before mourned, perhaps for itself as much as for the humble “Doc”.

“[H]e deserves to be remembered with understanding and respect”, Mara later recorded in his memoirs.

But understanding and respect were qualities not yet appreciated by the young republic. Source: MULTICULTURALISM & RECONCILIATION IN AN INDULGENT REPUBLIC..More details later!