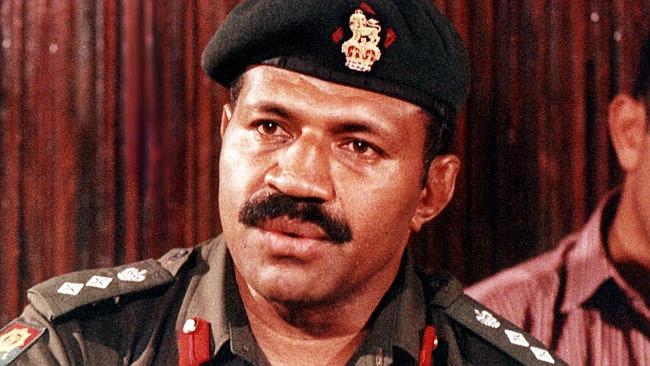

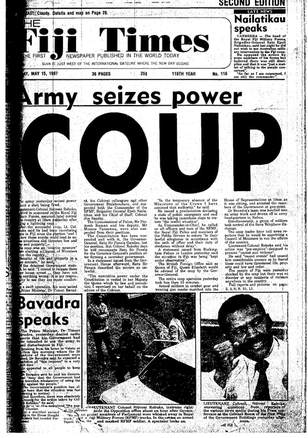

We say to Rabuka's side-kick in Parliament: The 1970 Constitution was SUPREME LAW until your coupist boss shredded it into fragments and imposed on Fiji his racist 1990 Constitution

While responding to President’s speech in Parliament this morning, Nawaikula kept talking about Sayed-Khaiyum. Nawaikula says the 2013 constitution is not the supreme law. He says the real constitution is the 1997 constitution because it has a mandate and contains the common will of the people. Nawaikula says the truth is that the true test for the validity of the 2013 constitution will come when the FijiFirst is removed. Source: Fijivillage News, 4 October 2017

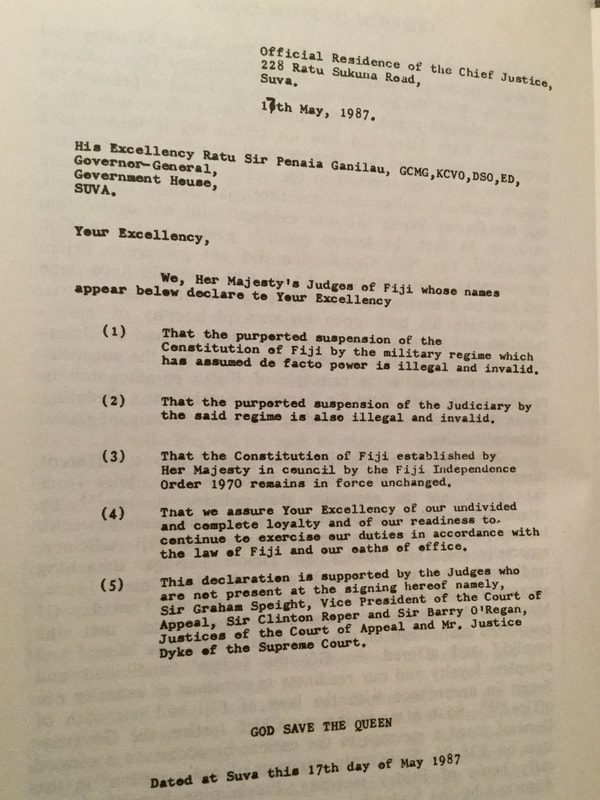

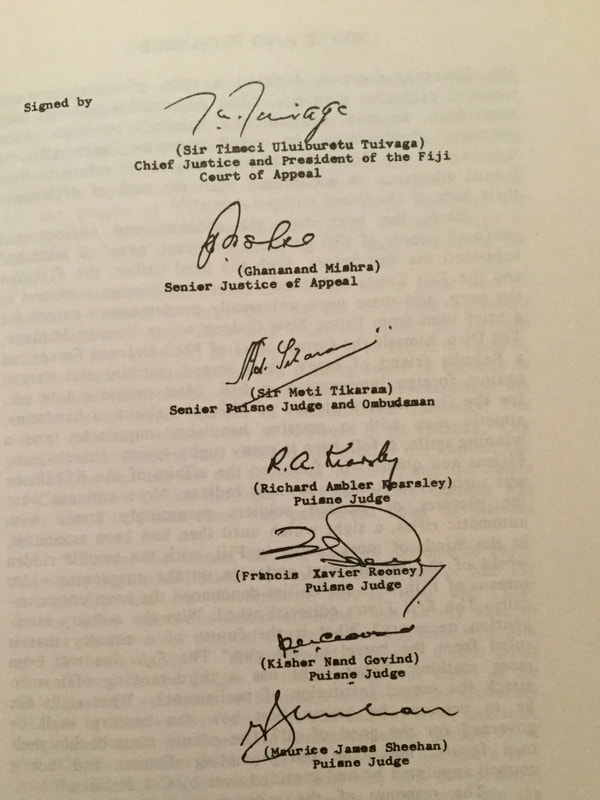

"That the purported suspension of the [1970] Constitution of Fiji by the [Rabuka] military regime which has assumed de facto power is illegal and invalid" - Chief Justice Sir Timoci Tuivaqa and his brother judges

It is time Nawaikula chooses: To Sober Up or Suck Up to Rabuka:

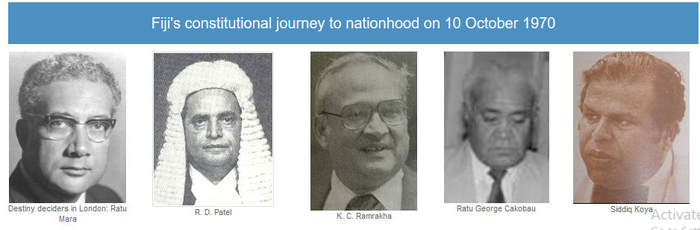

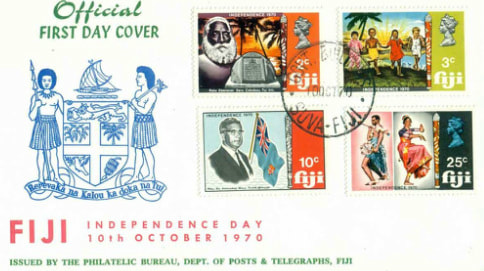

| Excerpt from Victor Lal, Fiji: Coups in Paradise The tenth of October is a memorable date in Fiji’s historical and political calendar. In 1874 it recorded the surrender of the islands’ sovereignty to Great Britain, and in 1970 the end of British rule and Fiji’s entry into the Commonwealth of Nations as an independent state. In August 1969 a series of discussions took place between the Alliance Party and the National Federation Party to consider further constitutional changes and, on 3 November 1969, the two major parties agreed that Fiji should become independent by way of Dominion status. This sudden, amicable agreement was possible because in October 1969, during the negotiations, the leader of the NFP, A. D. Patel, had died. Hs successor, Siddiq Koya, a lawyer by profession, proved flexible and conciliatory towards the Alliance Party and its leader Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara; also, the gesture on the part of the Fijians temporarily forced the Indo-Fijians to shelve their demand for common roll. During the series of discussions in August 1969 the Alliance favoured Dominion status, with the Queen as constitutional monarch, represented in Fiji by a Governor-General. The NFP envisaged Fiji as an independent state, with an elected President of Fijian origin as its head, but Fiji should be a member of the Commonwealth. Both parties agreed on Commonwealth membership and that Fiji should proceed to independence. Events abroad had again influenced their decision; this time it was the violence in Mauritius, on 12 March 1968, the day of Independence. Following the broad agreement between the two parties, Lord Shepherd, the British Minister of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, visited Fiji from 26 January to 2 February 1970, “to acquaint himself at first hand with the position reached in the talks”. The parties agreed on most issues except on the composition of the Legislature and method of election. The Constitutional Conference was subsequently held at Marlborough House in London from 20 April to 5 May 1970. On 30 April, in the course of the Conference, Ratu Mara announced that agreement had been reached on the interim solution. He told the Conference, in plenary session, that he had discussed the matter further with Koya, the Leader of the Opposition, and they had agreed that he should make the following statement to the Conference: “The Alliance Party stated that as in 1965 they recognised that election on a common roll basis was a desirable long-term objective but they could not agree to its introduction at the present state. On the other hand the National Federation Party reiterated its stand that common roll could be introduced immediately in Fiji and could form the basis of the next general election without in any way one race dominating others but resulting in a justly representative national Parliament. The two parties having regard to the national good and for peace, order and good government of independent Fiji reached the following conclusions...that the democratic processes of Fiji should be through political parties, each with its own political philosophy and programme for the economic and social advancement of the people of Fiji cutting across race, colour and creed, and that all should work to this end. The Conference called upon the Government of Fiji to see the immediate completion of the extension of common roll to all towns and township elections, in particular, Lautoka and Suva. | |

The Conference further agreed that the Lowe House should be composed as follows: Fijian (Communal, 12, National Roll, 10); Indo-Fijian (Communal 12, National, 10), General (Communal, 3, National, 5).

In agreeing to this composition for the Lower House the parties acknowledged that this is an interim solution and provides for the first House of Representatives elected after Independence, and the Parliament would, after considering the Royal Commission Report, provide through legislation for the composition and method of election of a new House of Representatives, and that such legislation so passed would be regarded as an entrenched part of the Constitution.”

It was also agreed that a Senate comprising 22 members be appointed by the Governor-General on the basis of nominations distributed as follows: Prime Minister, seven; Leader of the Opposition, six: Great Council of Chiefs, eight; and Council of Rotuma, one. Nevertheless, the Senate, which was created at the suggestion of the Indo-Fijian delegates, was designed to serve as protector of the land rights and customs of the native Fijians.

Any legislation that affected these rights could be vetoed by the representatives of the Great Council of Chiefs. It may be noted that, while the Indo-Fijian leaders opted for a small piece of the political pie rather than none, the 1970 Marlborough House Conference was a solid victory for native Fijians. The Fijians were a minority and the Constitution went out of its way to safeguard their interests.

That the British had devolved upon the two major communities the responsibility of reaching an agreement provoked severe criticism, and the Indo-Fijian leaders did not hesitate to raise the issue. The following exchange between R. D. Patel (who became the first Speaker of the House of Representatives after independence) and Lord Shepherd, exemplifies the situation:

R. D. Patel: Surely, Britain had kept the races apart for the last 90 years, and now it must take some responsibility to bring them together. It cannot just leave us to our own devices.

Lord Shepherd: My dear chap, if I had to assume responsibility for the sins of my British forefathers for the past 300 years, I would hardly be sitting here as a Minister of the Crown. Indeed, I would be in sackcloth and ashes doing penance in some monastery.

In his 1971 New Year message, Ratu Mara, as Prime Minister of independent Fiji, described 1970 as the “year of hope fulfilled”. The peaceful transition from colony to independence for him was “a pearl of great price which can perhaps be shared with the world at large.”

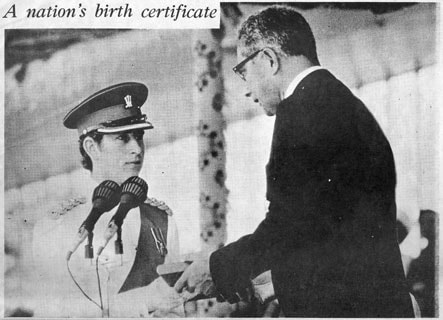

On 10 October 1970 Fiji became independent, ending some of the social and political tensions of over three-quarters of a century of British rule. The country moved into an equable political climate of a parliamentary democracy in which rival communal parties were to compete for power. The political leaders signed the 1970 Constitution, which assumed the operation of representative and responsible government using the Westminster model, but future conflicts were by no means unlikely.

Tragically, Fiji has been turned from paradise to coup coup land