*In 2006, in one of my regular Opinion Column in the Fiji Sun, I had defended the late Bune's right to criticize the i-taukei Chiefs, especially Ratu Naiqama Lalabalavu. Seventeen years later, in July 2023, Bune remembered my piece and was wondering if I still had a copy. I couldn't find the original Fiji Sun copy but I found a print-out in my 'Fiji File' which I scanned and e-mailed it to him.

*Sadly, last week he had become too ill to answer my question: 'Bula Kai, What is your take on Vasu's statement on the GCC?'

*Bune was taken to the Lautoka Hospital, early dawn, Tuesday morning of the 14 November 23, where he was admitted to the Trauma Unit. When Sitiveni Rabuka was informed of his dire condition, on Saturday evening 18 November, he contacted Lautoka Hospital and had him moved to the Nadi Private Hospital, which was far better equipped to deal with Bune's condition, so that by Monday, 20 November he was at the Nadi Private Hospital.

*Bune had arrived in very appalling condition, which did not reflect well on the medical care that he was receiving at the Trauma Unit, Lautoka Hospital. The doctors at the Nadi Private Hospital fought to save his life. *They managed to prolong his life a few more days. From what we gather, the operation they performed on him on Monday evening went well. Bune managed to open his eyes and speak to one of the nurses but he was still in a very delicate and fragile state, and was not completely out of the danger zone.

*He managed to hang on to life up to Wednesday morning, 22 November, when he passed away at 6.41am. May he rest in peace.

*Bune had, besides prostrate cancer, suffered a stroke a few weeks ago after which he was bedridden and reportedly paralysed from the waist down but his mind was still very sharp, and he had remained active on his I-Pad. He appreciated the company of his friends and the staff who at the RSL in Lautoka were basically looking after him. |

From the Archives, 2012

This article published in the Sun in November 2006 is especially pertinent now while people are again talking of the Great Council of Chiefs, chiefly authority, custom and land. Croz Walsh

'Wherever I go now,’ the first British colonial governor Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon wrote, ‘the natives shout Woh! and crouch down, as before their own great chiefs, and they admit and understand that I am their master’.

His house was declared tabu: all persons passing it on the road or sailing before it in canoes, gave the tama, or shout of respect to a high chief. The people had no choice, for it was Gordon who had created the Bose Levu Vakaturaga or the Great Council of Chiefs, and had come to see himself as chief of the Fijian chiefs.

The GCC is, therefore, merely a colonial invention, which Gordon had created in order to rule Fiji through the chiefs. In fact, there was nothing new about Gordon’s invention, for the British had devised similar institutions, to rule Africa through the African chiefs on that continent.

The British also introduced the African native system of government into Fiji. In other words, the British were not treating the Fijian chiefs as special although they couched their policies in that term.

However, Gordon mixed and matched titles to create Fijian customs, traditions, and institutions. He borrowed the title ‘Buli’ from Bua, where it applied to a minor chief, and that of ‘Roko Tui’ from the head of the priestly clan in Tailevu and Rewa.

It was not long before the Fijian chiefs began to accept the institution and the paraphernalia and the inventions that went with it as uniquely Fijian. They also swore to obey everything that Governor commanded them to perform during the long years of British colonialism.

As historians of Fiji have argued, there is no evidence that the councils set up by Gordon were ‘purely native and of spontaneous growth’.

The chiefs rarely met in Council until the imported institutions of government required them to do so.

In 1875 the Government interpreter David Wilkinson refused to accept that the GCC was a body based on Fijian tradition: ‘The Fijian custom being that high Chiefs seldom, if ever, meet each other in Council.’ The GCC was directly subject to Gordon’s authority, the regulation that provided for its establishment stating:

‘The Governor is the originator of the Council and he alone can open its proceedings’.

The power Gordon held over the GCC was manifestly demonstrated when he threatened to abolish it on finding out that some of its chiefly members were drunk.

He recorded his dealings with the chiefs in his personal diaries that he published in four volumes between 1897 and 1912.

The disputes over chiefly successions, which are still prevalent today, were rampant. Ratu Bonaveidogo of Macuata, giving evidence on the position of Tui Macuata when asked to explain the customs of his tribe in the matter of chiefly succession replied that the custom was to fight about it.

Another contentious issue was the ownership of land, which has again reared its ugly head following the introduction of the Indigenous Lands Claims Tribunal and the Qoliqoli Bills.

The Bua Government was the earliest in the country to have taken the effective measure to control the sale of land in Fiji, passing, in 1866, an ‘Act to regulate the sale and leasing of lands within the kingdom and state of Bua’.

The Act stripped the power of the chiefs to sell or lease land and vested it to the Government, which fixed the price and shared the profits with the landowners. However, any rebellious tribe who did not conform to Tui Bua or conspired against him, faced expulsion, as the Korovatu people found to their cost in 1866.

The Yasawa islands, conquered by Ma’afu on behalf of Tui Bua, was not spared – the rebellious chiefs of Nacula and Tavewa found their islands sold to planter Hennings as a punishment for supporting Bau.

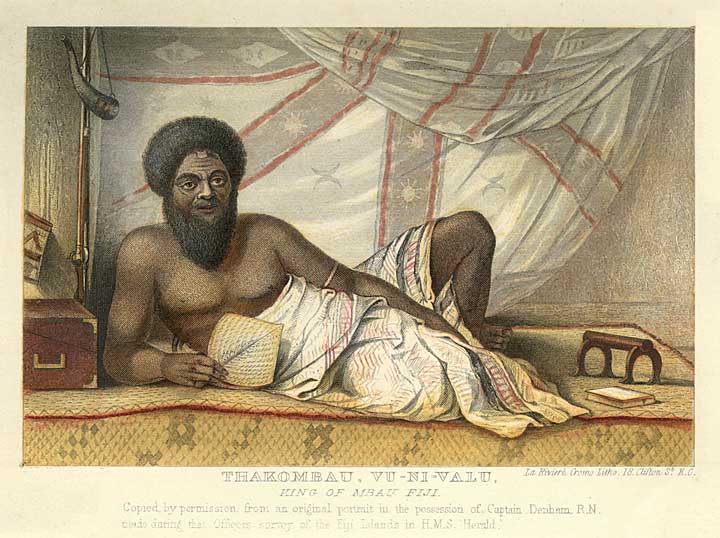

Other chiefs, especially Ratu Seru Cakobau and the Tui Cakau were equally ruthless. A year before the Deed of Cession was signed, as historian Peter France and others have demonstrated, the survivors from the vanua of Magodro, Qaliyalatina, and Naloto, following the outbreak of war in Ba, were deported from their lands and offered for sale to white settlers, their lands being confiscated and included in the offer of cession to British Crown.

The Lovoni people, who had revolted against Cakobau, had their lands mortgaged and sold by auction, and they themselves were sold as plantation labour at three pounds a head. Cakobau also gave away 200,000 acres of land to the Polynesian Company, including the Suva Harbour, in exchange for the payment of debts to the Americans. King Cakobau’s son Ratu Epeli, on being appointed as Lieutenant-Governor of Ba and Yasawa sold most of the northern islands to European settlers.

Commenting on the deeds of sale in Nasarawaqa, Bua, the Lands Commission noted that ‘they bear the signature of an extravagant of chiefs, most of whom had very little to do with the lands sold, culminating with the name of Ratu Epeli of Bau, who had about as much authority at that time, and in that part of Fiji as the Emperor of China’. Chief Ritova had alienated over 100,000 acres of land along the coast of Vanuabalavu.

The Tui Cakau had even given away the rights of levy over Cicia to Ma’afu in exchange for the Tongan chief’s canoes. Ma’afu had also taken up residence at Lomaloma after putting down a rebellion on Vanuabalavu and assuming control over the islands. The Tui Cakau had also given away a coastal stretch on Natewa Bay to planter Hennings, and also sold Natasa in Natewa, without informing its occupants. The lists are endless.

The missionaries were notey appropriated huge tracts of land in the name of Christianity and civilisation.

It was against that background that behind – thGovernor Gordon finally summoned the chiefs in 1876 to outline the traditionally recognised rights to land so that legislation could be framed.The chiefs were not sure of the immemorial traditions to land rights. The Land Commissioners equally struggled, with Basil Thomson concluding as follows: ‘The Fijians had no territorial roots. It is not too much to say that no tribe now occupies the land held by its fathers two centuries ago.’

In the end the present system of land ownership was devised, with the Native Lands Trust Board as the guardian of land rights in Fiji. Those championing for the introduction of the Qoliqoli and Indigenous Lands Claims Bill have, as I have written elsewhere, law on their side. However, the whole land debate and legislation of the old was framed in the aftermath of native and settler disputes over land rights in Fiji.

Sir Arthur Gordon had never factored into his policy the likelihood of Fijians refusing to share with other fellow Fijians the proceeds of their tribal lands, seas, and foreshores in the 21st Century. Commodore Voreqe Bainimarama and other interior Fijians have nothing to benefit from the Qoliqoli Bill, and it is this that I suspect that is driving him and others to oppose it to the bitter end. He even went to the extent of claiming that the Lauans pushing for the Bill will not be affected from its fall out. After all, the Lauan chief Ma’afu was not even a signatory to the Deed of Cession, which had unconditionally ceded Fiji to Queen Victoria in 1874.

The question that follows is who should be held accountable for the wanton loss of Fijian lands? Who should pay compensation? It is quite clear that it should be the descendants of the chiefs and the churches in Fiji. It is wrong, especially for the present chiefs and the Government, to blame only the colonialists and white settlers.

It was the present chiefs’ ancestors who are the real culprits, for it was they who sold the lands or sold lands over which they had little claim in the first instance to white settlers, planters, and missionaries.

The Governor Sir Arthur Gordon had come up with a land policy in the 19th Century to ensure that Fiji survived under his governorship.

According to one of his successors, Im Thurn, ‘It is too true that all Sir Arthur Gordon’s successors as Governors of Fiji have unquestionably followed him into the pit which he first dug. We-for I am a culprit too-followed his lead in thinking that the Fijians had good claims to the surplus land’.

It should not come as any surprise that in 1907 Gordon, by now Lord Stanmore, supported his land policy in the British House of Lords, for the chiefs had also given away two islands to him as a gift from the Fijian people.

Which Fijian people? And who owned those two lands to which Gordon had become the turaga taukei – a land owning chief in the country? Sadly the Fiji of 1876 is very different from the Fiji of 2006. The current stand-off between the Prime Minister and the Commodore on the Qoliqoli Bill is a testimony to that fact.

His house was declared tabu: all persons passing it on the road or sailing before it in canoes, gave the tama, or shout of respect to a high chief. The people had no choice, for it was Gordon who had created the Bose Levu Vakaturaga or the Great Council of Chiefs, and had come to see himself as chief of the Fijian chiefs.

The GCC is, therefore, merely a colonial invention, which Gordon had created in order to rule Fiji through the chiefs. In fact, there was nothing new about Gordon’s invention, for the British had devised similar institutions, to rule Africa through the African chiefs on that continent.

The British also introduced the African native system of government into Fiji. In other words, the British were not treating the Fijian chiefs as special although they couched their policies in that term.

However, Gordon mixed and matched titles to create Fijian customs, traditions, and institutions. He borrowed the title ‘Buli’ from Bua, where it applied to a minor chief, and that of ‘Roko Tui’ from the head of the priestly clan in Tailevu and Rewa.

It was not long before the Fijian chiefs began to accept the institution and the paraphernalia and the inventions that went with it as uniquely Fijian. They also swore to obey everything that Governor commanded them to perform during the long years of British colonialism.

As historians of Fiji have argued, there is no evidence that the councils set up by Gordon were ‘purely native and of spontaneous growth’.

The chiefs rarely met in Council until the imported institutions of government required them to do so.

In 1875 the Government interpreter David Wilkinson refused to accept that the GCC was a body based on Fijian tradition: ‘The Fijian custom being that high Chiefs seldom, if ever, meet each other in Council.’ The GCC was directly subject to Gordon’s authority, the regulation that provided for its establishment stating:

‘The Governor is the originator of the Council and he alone can open its proceedings’.

The power Gordon held over the GCC was manifestly demonstrated when he threatened to abolish it on finding out that some of its chiefly members were drunk.

He recorded his dealings with the chiefs in his personal diaries that he published in four volumes between 1897 and 1912.

The disputes over chiefly successions, which are still prevalent today, were rampant. Ratu Bonaveidogo of Macuata, giving evidence on the position of Tui Macuata when asked to explain the customs of his tribe in the matter of chiefly succession replied that the custom was to fight about it.

Another contentious issue was the ownership of land, which has again reared its ugly head following the introduction of the Indigenous Lands Claims Tribunal and the Qoliqoli Bills.

The Bua Government was the earliest in the country to have taken the effective measure to control the sale of land in Fiji, passing, in 1866, an ‘Act to regulate the sale and leasing of lands within the kingdom and state of Bua’.

The Act stripped the power of the chiefs to sell or lease land and vested it to the Government, which fixed the price and shared the profits with the landowners. However, any rebellious tribe who did not conform to Tui Bua or conspired against him, faced expulsion, as the Korovatu people found to their cost in 1866.

The Yasawa islands, conquered by Ma’afu on behalf of Tui Bua, was not spared – the rebellious chiefs of Nacula and Tavewa found their islands sold to planter Hennings as a punishment for supporting Bau.

Other chiefs, especially Ratu Seru Cakobau and the Tui Cakau were equally ruthless. A year before the Deed of Cession was signed, as historian Peter France and others have demonstrated, the survivors from the vanua of Magodro, Qaliyalatina, and Naloto, following the outbreak of war in Ba, were deported from their lands and offered for sale to white settlers, their lands being confiscated and included in the offer of cession to British Crown.

The Lovoni people, who had revolted against Cakobau, had their lands mortgaged and sold by auction, and they themselves were sold as plantation labour at three pounds a head. Cakobau also gave away 200,000 acres of land to the Polynesian Company, including the Suva Harbour, in exchange for the payment of debts to the Americans. King Cakobau’s son Ratu Epeli, on being appointed as Lieutenant-Governor of Ba and Yasawa sold most of the northern islands to European settlers.

Commenting on the deeds of sale in Nasarawaqa, Bua, the Lands Commission noted that ‘they bear the signature of an extravagant of chiefs, most of whom had very little to do with the lands sold, culminating with the name of Ratu Epeli of Bau, who had about as much authority at that time, and in that part of Fiji as the Emperor of China’. Chief Ritova had alienated over 100,000 acres of land along the coast of Vanuabalavu.

The Tui Cakau had even given away the rights of levy over Cicia to Ma’afu in exchange for the Tongan chief’s canoes. Ma’afu had also taken up residence at Lomaloma after putting down a rebellion on Vanuabalavu and assuming control over the islands. The Tui Cakau had also given away a coastal stretch on Natewa Bay to planter Hennings, and also sold Natasa in Natewa, without informing its occupants. The lists are endless.

The missionaries were notey appropriated huge tracts of land in the name of Christianity and civilisation.

It was against that background that behind – thGovernor Gordon finally summoned the chiefs in 1876 to outline the traditionally recognised rights to land so that legislation could be framed.The chiefs were not sure of the immemorial traditions to land rights. The Land Commissioners equally struggled, with Basil Thomson concluding as follows: ‘The Fijians had no territorial roots. It is not too much to say that no tribe now occupies the land held by its fathers two centuries ago.’

In the end the present system of land ownership was devised, with the Native Lands Trust Board as the guardian of land rights in Fiji. Those championing for the introduction of the Qoliqoli and Indigenous Lands Claims Bill have, as I have written elsewhere, law on their side. However, the whole land debate and legislation of the old was framed in the aftermath of native and settler disputes over land rights in Fiji.

Sir Arthur Gordon had never factored into his policy the likelihood of Fijians refusing to share with other fellow Fijians the proceeds of their tribal lands, seas, and foreshores in the 21st Century. Commodore Voreqe Bainimarama and other interior Fijians have nothing to benefit from the Qoliqoli Bill, and it is this that I suspect that is driving him and others to oppose it to the bitter end. He even went to the extent of claiming that the Lauans pushing for the Bill will not be affected from its fall out. After all, the Lauan chief Ma’afu was not even a signatory to the Deed of Cession, which had unconditionally ceded Fiji to Queen Victoria in 1874.

The question that follows is who should be held accountable for the wanton loss of Fijian lands? Who should pay compensation? It is quite clear that it should be the descendants of the chiefs and the churches in Fiji. It is wrong, especially for the present chiefs and the Government, to blame only the colonialists and white settlers.

It was the present chiefs’ ancestors who are the real culprits, for it was they who sold the lands or sold lands over which they had little claim in the first instance to white settlers, planters, and missionaries.

The Governor Sir Arthur Gordon had come up with a land policy in the 19th Century to ensure that Fiji survived under his governorship.

According to one of his successors, Im Thurn, ‘It is too true that all Sir Arthur Gordon’s successors as Governors of Fiji have unquestionably followed him into the pit which he first dug. We-for I am a culprit too-followed his lead in thinking that the Fijians had good claims to the surplus land’.

It should not come as any surprise that in 1907 Gordon, by now Lord Stanmore, supported his land policy in the British House of Lords, for the chiefs had also given away two islands to him as a gift from the Fijian people.

Which Fijian people? And who owned those two lands to which Gordon had become the turaga taukei – a land owning chief in the country? Sadly the Fiji of 1876 is very different from the Fiji of 2006. The current stand-off between the Prime Minister and the Commodore on the Qoliqoli Bill is a testimony to that fact.