SLAVERY COMPENSATION: British historian David Olusoga told The Observer: ‘While governments stubbornly refuse to engage with growing calls for reparations... there are families, companies, universities, charities and other organisations who are acknowledging their historic links to slavery and empire.’

Laura Trevelyan's aristocratic relatives had more than 1,000 slaves across six sugar plantations on the Caribbean island in the 19th century. The BBC journalist, based in New York, said her family is apologising 'for the role our ancestors played in enslavement'.

They will now hand over £100,000 to set up a community fund for economic development on the island. Ms Trevelyan, 54, said seven family members will also travel to Grenada this month to issue a public apology. She told the BBC her ancestors had received about £34,000 in 1834 - the year after slavery was abolished in the UK - as compensation for the loss of 'property'. This equates to about £3million today.

She recognised that giving £100,000 almost 200 years later could seem 'inadequate', but said: 'I hope that we're setting an example.' Ms Trevelyan visited Grenada for a documentary last year and said: 'I felt ashamed, and I also felt that it was my duty. You can't repair the past but you can acknowledge the pain.'Laura Trevelyan's aristocratic relatives had more than 1,000 slaves across six sugar plantations on the Caribbean island in the 19th century.

The BBC journalist, based in New York, said her family is apologising 'for the role our ancestors played in enslavement'. They will now hand over £100,000 to set up a community fund for economic development on the island. Ms Trevelyan, 54, said seven family members will also travel to Grenada this month to issue a public apology. She told the BBC her ancestors had received about £34,000 in 1834 - the year after slavery was abolished in the UK - as compensation for the loss of 'property'. This equates to about £3million today. She recognised that giving £100,000 almost 200 years later could seem 'inadequate', but said: 'I hope that we're setting an example.'

Ms Trevelyan visited Grenada for a documentary last year and said: 'I felt ashamed, and I also felt that it was my duty. You can't repair the past but you can acknowledge the pain.'

They will now hand over £100,000 to set up a community fund for economic development on the island. Ms Trevelyan, 54, said seven family members will also travel to Grenada this month to issue a public apology. She told the BBC her ancestors had received about £34,000 in 1834 - the year after slavery was abolished in the UK - as compensation for the loss of 'property'. This equates to about £3million today.

She recognised that giving £100,000 almost 200 years later could seem 'inadequate', but said: 'I hope that we're setting an example.' Ms Trevelyan visited Grenada for a documentary last year and said: 'I felt ashamed, and I also felt that it was my duty. You can't repair the past but you can acknowledge the pain.'Laura Trevelyan's aristocratic relatives had more than 1,000 slaves across six sugar plantations on the Caribbean island in the 19th century.

The BBC journalist, based in New York, said her family is apologising 'for the role our ancestors played in enslavement'. They will now hand over £100,000 to set up a community fund for economic development on the island. Ms Trevelyan, 54, said seven family members will also travel to Grenada this month to issue a public apology. She told the BBC her ancestors had received about £34,000 in 1834 - the year after slavery was abolished in the UK - as compensation for the loss of 'property'. This equates to about £3million today. She recognised that giving £100,000 almost 200 years later could seem 'inadequate', but said: 'I hope that we're setting an example.'

Ms Trevelyan visited Grenada for a documentary last year and said: 'I felt ashamed, and I also felt that it was my duty. You can't repair the past but you can acknowledge the pain.'

Fijileaks: The Great Council of Chiefs that will be reinstated in May by the Rabuka Coalition Government is a product of Governor Sir Arthur Gordon who introduced Indian indentured labour into Fiji. The sugar produced by the coolies not only sustained the colony but the CHIEFS enjoyed a lavish lifestyle. In fact, the Indo-Fijians' ancestors (the Indian coolies) were uprooted from British India to prevent the Fijian (i-Taukei) traditional way of life from disintegrating. Today, BIMAN PRASAD is indirectly bringing back the Great Council of Chiefs.

Where is the Ministry of Multi-Ethnic Affairs?

He must be told to PAY UP reparation to the Indo-Fijians.

A special trust fund must be set up to compensate them

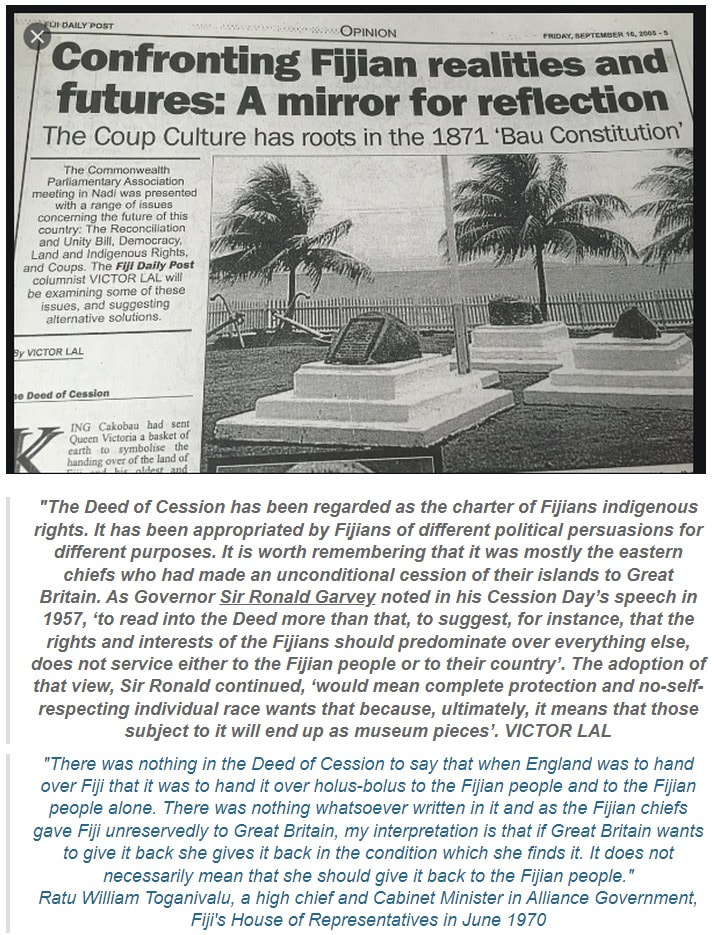

How did the chiefs come to cede the country to Great Britain on 10 October 1874? Which chiefs affixed their signatures to the historical deed? What was ceded to Queen Victoria of England and the Empress of India? It should be pointed out that the offer of cession was made as far back as 1859 but I will confine myself to the last few months leading up to the cession.

The article is written primarily for the general reader because the research findings of academics (including my own work), who have worked on the historical documents in the National Archives in Fiji and the Public Records Office in London, are seldom available to the general public.

Here I will give a fragmentary historical snapshot from the documents. I have also decided to retain the original names of all those involved in the cession as it appeared in the documents and also of the places, to give the narrative a sense of history and immediacy.

On 15 July 1874, the Earl of Carnarvon (Lord Carnarvon), the British minister responsible for the colonies, informed Sir Hercules Robinson, the governor of New South Wales in Australia, that the British government had determined that it was necessary to decline the acceptance of the cession of Fiji on the conditions appended, with the signature of Mr Thurston, to the Commissioner’s Report, but would recommend Queen Victoria to accept it on the general understanding, namely, that the chiefs, withdrawing all conditions, would trust to the generosity and justice of Her Majesty - the Queen of England.

Sir Hercules was invested with authority to act alone on the question of annexation. In telegrams dated the 15th, 16th, and 17th August, Sir Hercules replied to Lord Carnarvon and asked, first, whether, in the event of an unconditional cession being made, he had the authority to act as he did in the case of Kowlun, near Hong Kong, i.e., to accept the cession in the Queen’s name, and make the best available temporary arrangements for the establishment of a provisional government, pending the issue of an Order in Council prescribing a form of constitution and providing for legislation

He next inquired what was to follow in the event of the chiefs declining to make an unconditional offer, as the existing temporary arrangement under which order was maintained by the Consuls supported by men of war could not continue. On 25 August, Lord Carnarvon telegraphed to Sir Hercules that he was at liberty to accent the cession of Fiji if it should be unconditional or virtually unconditional, and to make arrangements for a temporary government.

Sir Hercules telegraphed on 6 September that he now only awaited Mr Parkes, the NSW Premier’s return to Sydney, and expected to start for Fiji in the Pearl on Saturday 12 September, which he did, and after a passage of eleven days, including a stopover of 24 hours at Norfolk Island, he arrived in Levuka harbour on the afternoon of 23 September.

Sir Hercules at once learnt that the general feeling amongst the white settlers, and also amongst some of the natives, in favour of annexation, was less strong than it had been in consequence of the recent debate in the British House of Lords upon Fiji, a report of which had been received at Levuka before his arrival. Persons whose interests were adverse, Sir Hercules told Lord Carnarvon, to the establishment of good government had taken advantage of expressions in Lord Carnarvon’s speech as to the Crown right of pre-emption in all lands, and as regards the “severe” form of government which would have to be adopted in the event of annexation, to excite distrust in the minds of both Europeans and natives on these subjects.

The wildest reports, Sir Hercules claimed, were circulated. All private lands were to be confiscated, and Fiji was to be a penal settlement. Already 300 marines had left Portsmouth to garrison the place and coerce the inhabitants! Sir Hercules merely mentioned these absurd rumours as their prevalence obliged him, in his subsequent negotiations, to correct as far as he could such “mischievous misrepresentation”.

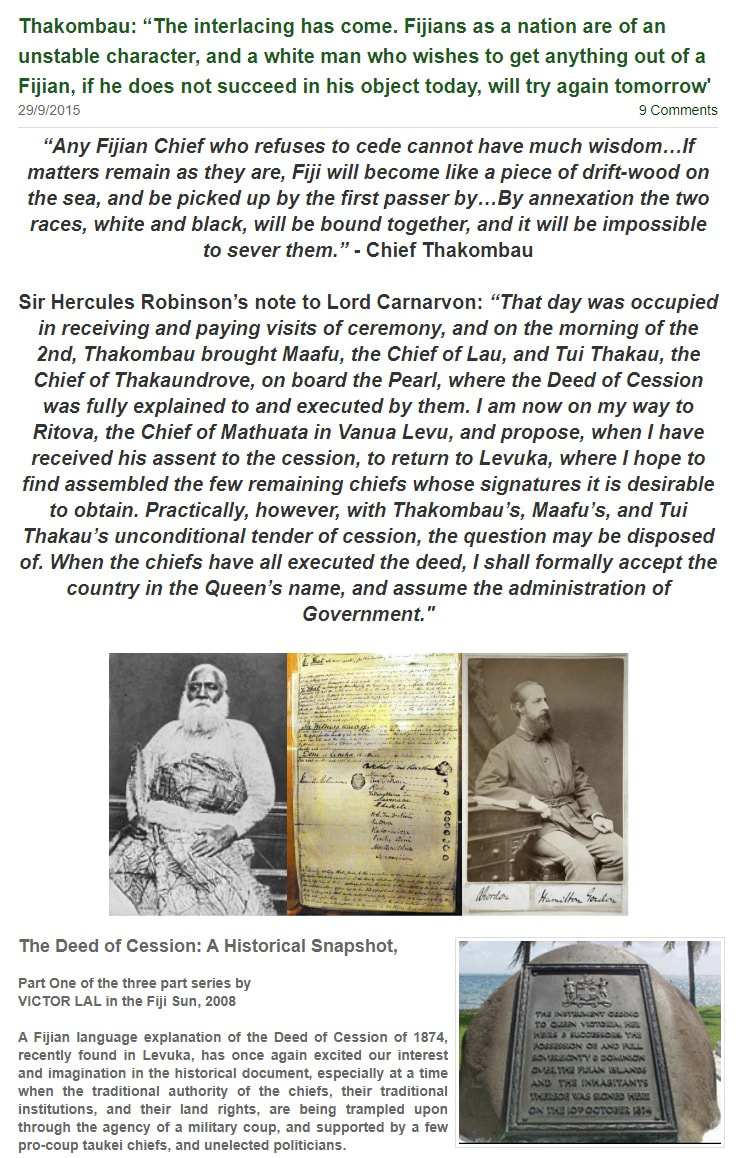

Upon the day after his arrival, Sir Hercules paid a formal visit to King Thakombau and four other principal ruling chiefs, who had come to Levuka to meet him. Sir Hercules annexed an extract from the Fiji Times of 26 September 1874 giving an account of this interview, during which no business was transacted; but he informed King Thakombau that whatever he (the King) felt inclined to enter upon business, he (Sir Hercules) would explain to the King frankly and fully the object of his visit.

On 25 September, Thakombau went to see Sir Hercules by appointment on board the ship Dido (the Pearl being engaged in coaling) and they then discussed unreservedly the question of annexation in all its bearings. Sir Hercules placed clearly before Thakombau the views of the British government. At first, according to Sir Hercules, Thakombau seemed much depressed and reserved, but before the close of the interview, which lasted for more than two hours, he became cheerful and communicative, illustrating the opinions which he expressed with much force and humour, and in a manner which showed clearly that he perfectly apprehended the points under discussion.

At the commencement of the interview, according to Sir Hercules, Thakombau said he would take time to think of his position, and would consult with other chiefs as to what was best to be done; but towards the close he expressed himself strongly in favour of an unconditional cession of Fiji to Queen Victoria, observing that, “any Fijian Chief who refuses to cede cannot have much wisdom…If matters remain as they are, Fiji will become like a piece of drift-wood on the sea, and be picked up by the first passer by…By annexation the two races, white and black, will be bound together, and it will be impossible to sever them.”

Thakombau ended as follows: “The interlacing has come. Fijians as a nation are of an unstable character, and a white man who wishes to get anything out of a Fijian, if he does not succeed in his object today, will try again tomorrow, until the Fijian is either wearied out or over persuaded, and gives in. But law will bind us together, and the stronger nation will lend stability to the weaker.” The result of the interview was, Sir Hercules concluded, on the whole, entirely satisfactory, and the views expressed by Thakombau displayed “so much intelligence and unselfishness that I am sure your Lordship will feel interested in perusing a full report of the conversation”.

On 28 September it was intimated to Sir Hercules a message from Thakombau that, after two days’ discussion in Council, he and the other chiefs then present in Levuka had agreed to the following resolution: “We give Fiji unreservedly to the Queen of Britain, that she may rule us justly and affectionately, and that we may live in peace and prosperity.”

Sir Hercules then forwarded to Thakombau a draft of the Deed of Cession which he (Sir Hercules) had prepared, and stated that, when it had been interpreted and fully explained to the chiefs, Sir Hercules would be prepared to accept the signatures of such of them as were in Levuka, and on its execution by the remainder of the ruling authorities Sir Hercules would formally accept the cession, and establish a provisional government until the Queen’s pleasure as to the future constitution of the islands could be known.

The following day, the 29 September, was devoted by the chiefs to the consideration of the Deed of Cession, and in the evening it was intimated to Sir Hercules that Thakombau and chiefs would be prepared to sign at Nasova, the public offices of Levuka, on the morning of the 30 September.

Sir Hercules accordingly proceeded to Nasova at 10 o’clock on the morning of the 30th, when Thakombau read and handed to Sir Hercules the formal resolution of the Council giving Fiji “unreservedly to the Queen”. The Deed of Cession was then read in Fijian, and the instrument executed by Thakombau and the four other ruling chiefs who were present.

Sir Hercules then invited Thakombau to accompany him on a tour of the islands to obtain the signature of Maafu and of other chiefs not then in Levuka, whose assent was necessary to the validity of the cession. This Thakombau at once cheerfully agreed to, and they left Levuka the same afternoon in the ships Pearl and Dido for Lomaloma, Maafu’s capital, at which place they arrived on the morning of 1 October.

According to Sir Hercules’ note to Lord Carnarvon: “That day was occupied in receiving and paying visits of ceremony, and on the morning of the 2nd, Thakombau brought Maafu, the Chief of Lau, and Tui Thakau, the Chief of Thakaundrove, on board the Pearl, where the Deed of Cession was fully explained to and executed by them. I am now on my way to Ritova, the Chief of Mathuata in Vanua Levu, and propose, when I have received his assent to the cession, to return to Levuka, where I hope to find assembled the few remaining chiefs whose signatures it is desirable to obtain. Practically, however, with Thakombau’s, Maafu’s, and Tui Thakau’s unconditional tender of cession, the question may be disposed of. When the chiefs have all executed the deed, I shall formally accept the country in the Queen’s name, and assume the administration of Government.”

There was one clause in the Deed of Cession upon which Sir Hercules thought it as well to make a few explanatory observations, and that referred to Clause 4, which dealt with the land in Fiji.

The article is written primarily for the general reader because the research findings of academics (including my own work), who have worked on the historical documents in the National Archives in Fiji and the Public Records Office in London, are seldom available to the general public.

Here I will give a fragmentary historical snapshot from the documents. I have also decided to retain the original names of all those involved in the cession as it appeared in the documents and also of the places, to give the narrative a sense of history and immediacy.

On 15 July 1874, the Earl of Carnarvon (Lord Carnarvon), the British minister responsible for the colonies, informed Sir Hercules Robinson, the governor of New South Wales in Australia, that the British government had determined that it was necessary to decline the acceptance of the cession of Fiji on the conditions appended, with the signature of Mr Thurston, to the Commissioner’s Report, but would recommend Queen Victoria to accept it on the general understanding, namely, that the chiefs, withdrawing all conditions, would trust to the generosity and justice of Her Majesty - the Queen of England.

Sir Hercules was invested with authority to act alone on the question of annexation. In telegrams dated the 15th, 16th, and 17th August, Sir Hercules replied to Lord Carnarvon and asked, first, whether, in the event of an unconditional cession being made, he had the authority to act as he did in the case of Kowlun, near Hong Kong, i.e., to accept the cession in the Queen’s name, and make the best available temporary arrangements for the establishment of a provisional government, pending the issue of an Order in Council prescribing a form of constitution and providing for legislation

He next inquired what was to follow in the event of the chiefs declining to make an unconditional offer, as the existing temporary arrangement under which order was maintained by the Consuls supported by men of war could not continue. On 25 August, Lord Carnarvon telegraphed to Sir Hercules that he was at liberty to accent the cession of Fiji if it should be unconditional or virtually unconditional, and to make arrangements for a temporary government.

Sir Hercules telegraphed on 6 September that he now only awaited Mr Parkes, the NSW Premier’s return to Sydney, and expected to start for Fiji in the Pearl on Saturday 12 September, which he did, and after a passage of eleven days, including a stopover of 24 hours at Norfolk Island, he arrived in Levuka harbour on the afternoon of 23 September.

Sir Hercules at once learnt that the general feeling amongst the white settlers, and also amongst some of the natives, in favour of annexation, was less strong than it had been in consequence of the recent debate in the British House of Lords upon Fiji, a report of which had been received at Levuka before his arrival. Persons whose interests were adverse, Sir Hercules told Lord Carnarvon, to the establishment of good government had taken advantage of expressions in Lord Carnarvon’s speech as to the Crown right of pre-emption in all lands, and as regards the “severe” form of government which would have to be adopted in the event of annexation, to excite distrust in the minds of both Europeans and natives on these subjects.

The wildest reports, Sir Hercules claimed, were circulated. All private lands were to be confiscated, and Fiji was to be a penal settlement. Already 300 marines had left Portsmouth to garrison the place and coerce the inhabitants! Sir Hercules merely mentioned these absurd rumours as their prevalence obliged him, in his subsequent negotiations, to correct as far as he could such “mischievous misrepresentation”.

Upon the day after his arrival, Sir Hercules paid a formal visit to King Thakombau and four other principal ruling chiefs, who had come to Levuka to meet him. Sir Hercules annexed an extract from the Fiji Times of 26 September 1874 giving an account of this interview, during which no business was transacted; but he informed King Thakombau that whatever he (the King) felt inclined to enter upon business, he (Sir Hercules) would explain to the King frankly and fully the object of his visit.

On 25 September, Thakombau went to see Sir Hercules by appointment on board the ship Dido (the Pearl being engaged in coaling) and they then discussed unreservedly the question of annexation in all its bearings. Sir Hercules placed clearly before Thakombau the views of the British government. At first, according to Sir Hercules, Thakombau seemed much depressed and reserved, but before the close of the interview, which lasted for more than two hours, he became cheerful and communicative, illustrating the opinions which he expressed with much force and humour, and in a manner which showed clearly that he perfectly apprehended the points under discussion.

At the commencement of the interview, according to Sir Hercules, Thakombau said he would take time to think of his position, and would consult with other chiefs as to what was best to be done; but towards the close he expressed himself strongly in favour of an unconditional cession of Fiji to Queen Victoria, observing that, “any Fijian Chief who refuses to cede cannot have much wisdom…If matters remain as they are, Fiji will become like a piece of drift-wood on the sea, and be picked up by the first passer by…By annexation the two races, white and black, will be bound together, and it will be impossible to sever them.”

Thakombau ended as follows: “The interlacing has come. Fijians as a nation are of an unstable character, and a white man who wishes to get anything out of a Fijian, if he does not succeed in his object today, will try again tomorrow, until the Fijian is either wearied out or over persuaded, and gives in. But law will bind us together, and the stronger nation will lend stability to the weaker.” The result of the interview was, Sir Hercules concluded, on the whole, entirely satisfactory, and the views expressed by Thakombau displayed “so much intelligence and unselfishness that I am sure your Lordship will feel interested in perusing a full report of the conversation”.

On 28 September it was intimated to Sir Hercules a message from Thakombau that, after two days’ discussion in Council, he and the other chiefs then present in Levuka had agreed to the following resolution: “We give Fiji unreservedly to the Queen of Britain, that she may rule us justly and affectionately, and that we may live in peace and prosperity.”

Sir Hercules then forwarded to Thakombau a draft of the Deed of Cession which he (Sir Hercules) had prepared, and stated that, when it had been interpreted and fully explained to the chiefs, Sir Hercules would be prepared to accept the signatures of such of them as were in Levuka, and on its execution by the remainder of the ruling authorities Sir Hercules would formally accept the cession, and establish a provisional government until the Queen’s pleasure as to the future constitution of the islands could be known.

The following day, the 29 September, was devoted by the chiefs to the consideration of the Deed of Cession, and in the evening it was intimated to Sir Hercules that Thakombau and chiefs would be prepared to sign at Nasova, the public offices of Levuka, on the morning of the 30 September.

Sir Hercules accordingly proceeded to Nasova at 10 o’clock on the morning of the 30th, when Thakombau read and handed to Sir Hercules the formal resolution of the Council giving Fiji “unreservedly to the Queen”. The Deed of Cession was then read in Fijian, and the instrument executed by Thakombau and the four other ruling chiefs who were present.

Sir Hercules then invited Thakombau to accompany him on a tour of the islands to obtain the signature of Maafu and of other chiefs not then in Levuka, whose assent was necessary to the validity of the cession. This Thakombau at once cheerfully agreed to, and they left Levuka the same afternoon in the ships Pearl and Dido for Lomaloma, Maafu’s capital, at which place they arrived on the morning of 1 October.

According to Sir Hercules’ note to Lord Carnarvon: “That day was occupied in receiving and paying visits of ceremony, and on the morning of the 2nd, Thakombau brought Maafu, the Chief of Lau, and Tui Thakau, the Chief of Thakaundrove, on board the Pearl, where the Deed of Cession was fully explained to and executed by them. I am now on my way to Ritova, the Chief of Mathuata in Vanua Levu, and propose, when I have received his assent to the cession, to return to Levuka, where I hope to find assembled the few remaining chiefs whose signatures it is desirable to obtain. Practically, however, with Thakombau’s, Maafu’s, and Tui Thakau’s unconditional tender of cession, the question may be disposed of. When the chiefs have all executed the deed, I shall formally accept the country in the Queen’s name, and assume the administration of Government.”

There was one clause in the Deed of Cession upon which Sir Hercules thought it as well to make a few explanatory observations, and that referred to Clause 4, which dealt with the land in Fiji.