"I’ve been following The Fiji Times since the days I first learnt to read and it brings me great sadness to think how perilously close narrow-mindedness has brought it to extinction."

Joint Conference of the New Zealand-Fiji Business Council

and the Fiji-New Zealand Business Council.

1l June, 2009. Auckland, N.Z.

Kia Ora, Ni Sa Bula, Namaste and G’Day.

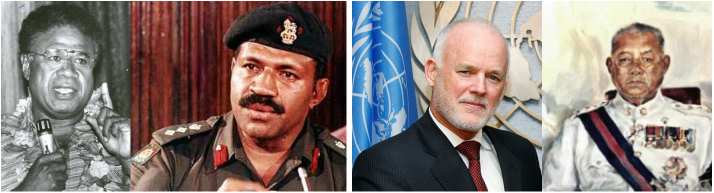

The central subject of my book Kava in the Blood is Fiji’s political crisis of 1987, a crisis brought on by a number of destabilising events, principally the two coups d’état executed by one Lieutenant-Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka. During that year of virtually daily national crisis, I was the permanent secretary of information for both the Mara and Bavadra governments, and was then the permanent secretary to the governor-general for the five months between the two coups. During those five months, on the advice of Fiji’s judiciary, with parliament and its ministers in abeyance, all executive authority of government rested in the office of my boss, the governor-general, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau.

In considering the current economic and political situation in Fiji, there are without doubt some meaningful lessons to be learnt from the events and issues of 1987 and in the time available to me this afternoon, I’d like to highlight some of those for you.

Before I do that, I should acknowledge there are many differences of circumstance between 1987 and where we’ve got to in Fiji in 2009. At the beginning of 1987 Fiji was still being touted as a model for the developing world and nobody had ever heard of a coup d’état, so much so that for much of the year locals talked about a ‘coop’ as in chicken-coop. Today Fiji is said to be in the grip of a ‘coup culture’ and nobody is particularly surprised when a constitution is set aside and the army steps in.

Another critical difference is that in 1987 The Queen was head of state of Fiji. For that to remain the case, certain conditions of governance had to be adhered to, including upholding the laws of Fiji. Today Fiji is a republic and sets its own rules.

The other significant difference is that in 1987 the army and the indigenous nationalists were in cahoots and the main agenda was one of strengthening the political and economic position of the indigenes, inevitably at the expense of the rest of the country. Today the army is the enemy of the indigenous nationalists and the regime’s expressed agenda is an end to racial thinking and to end corruption in government.

The fundamental similarity of 1987 and the present is that democratically-elected governments were overthrown by the Fiji military forces. Under the current situation, whatever may be said otherwise, the Military Council is where real power lies. In realpolitik terms in 1987, final executive authority did not rest where the law said it did, for when it suited the army on September 25th, a second coup d’état was staged. As a part of that second coup, the governor-general was effectively put under house arrest and I spent four days behind bars at Queen Elizabeth Barracks.

The first point I’d like to make is: expect the unexpected. When the first coup d’état took place in Fiji on May 14th 1987, I was a hundred metres from the epicentre explaining to overseas journalists why things like coups d’état would never happen in Fiji. Today as business-people working in the Fiji environment, we need to be adept at reading the signs. As an American business-guru once said, look after the down-side and the up-side will look after itself.

My second point relates to the role of the international community in restoring an internationally acceptable outcome to Fiji’s situation. Contrary to what one would expect, the views of the international community are not a priority when you’re managing a national crisis that has the daily potential to blow up in everyone’s faces. In 1987 Ratu Sir Penaia’s primary challenge was to produce a Fiji solution to a Fiji problem, for he was fully aware the days had passed when the indigenous Fijians were prepared to accept a foreign solution. The international accountability of his actions was safeguarded in his own thinking by his need to satisfy The Queen, the head of the Commonwealth and still the head of state of Fiji, as to his ultimate solution of the crisis. In Kava in the Blood, I outline how we kept Buckingham Palace briefed on our progress.

The governor-general produced a national solution after five months of concerted negotiation in an agreement now known as the Deuba Accord. The accord was essentially an agreement by the elected political leaders of the deposed parliament to join in a caretaker government, under his leadership, that would address the crisis issues at hand, including bi-partisan review of the constitution. It was a remarkable outcome and within hours of the accord’s announcement foreign governments, including those of Australia and New Zealand, were ringing in their congratulations and promising immediate cessation of sanctions and resumption of aid.

The flaw in the agreement was that the Ratu Sir Penaia had taken Sitiveni Rabuka and his kitchen-cabinet of indigenous nationalists at their word. Rabuka had promised Ratu Sir Penaia they would support him and the outcome of his labours, a promise made in accordance with his role as the governor-general, the country’s commander-in-chief, and as their traditional paramount chief, Na Turaga na Tui Cakau. A fortnight later and Fiji had become the reluctant republic.

Looking back to 1987, it is instructive to remember how singularly unhelpful the governments of Australia and New Zealand were to Ratu Sir Penaia in his efforts to achieve national reconciliation. Prime Minister Hawke failed to make any positive impression, while Prime Minister Lange flirted with fantasies of gunboat diplomacy. Their perspectives were completely understandable, for the May coup d’état had struck at the heart of their countries’ long adherence to the principles of parliamentary democracy and their former comfort in having Fiji as a firm regional partner in this tradition.

Fiji’s former prime minister Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara took the rejection by Hawke and Lange more personally and when asked by a journalist what Fiji’s foreign policy priority should be, he replied, ‘To get in touch with as many countries as possible, particularly the people of the eastern side of the Pacific, from Japan, China, South Korea, Malaysia, which have been very supportive of us, to see whether they will be able to substitute the goods that will not be coming from Australia and New Zealand.’

When we examine the situation today, we see little has changed. In the Asia/Pacific region the Australian and New Zealand governments are the odd ones out in refusing to deal with the Fiji regime. While the ambassadors of China and India come and go from the prime minister’s office with many an embrace and many a promise of support, the high commissioners of Australia and New Zealand are under orders to maintain themselves in splendid isolation.

With Australia and New Zealand absent from the corridors of power in Suva, we are told in Australia that the Chinese government has assured Canberra it won’t be doing anything in Fiji to take advantage of the situation. Anyone naïve enough in the arts of geopolitics to believe that, will presumably also believe that Beijing gives a fig what form of government exists in Fiji as long as it has an open door to China. It is plain to see that with India and China the two looming super-powers of Asia-Pacific, whether Fiji is governed by a military regime or a Fijian nationalist majority government, Canberra and Wellington’s policy is driving Fiji north.

It is true that the Pacific Forum has manoeuvred itself, some would say ‘been manoeuvred into’, expelling Fiji from its ranks. ‘Democracy or dust’ seems to be the thinking. There are two sad consequences to this piece of regional folly. The first is that the foundations of the Forum have been grievously damaged. The shortcomings of this month’s meeting on regional security in Suva were a clear demonstration of that.

The Forum has been the beating heart of Australian and New Zealand cooperation with the Pacific Islands for nearly four decades now, so it has been a self-defeating blow that Canberra and Wellington have struck in forcing Fiji’s expulsion. Meanwhile the Melanesian Spearhead Group, with its front-door open, not to the south, but north to China, has imposed no sanctions on Fiji’s membership. Thanks in part to having China as its patron, the MSG is growing in strength, probably at the expense of the Forum’s influence.

The Fiji tourism industry has been damaged by travel advisories warning of physical dangers, when the record shows otherwise. A report I read this week by the Australian Government’s Institute of Criminology entitled ‘The Murder of Overseas Visitors in Australia’ clearly demonstrates there’s far higher potential for Australian tourists to come to harm in Europe or the United States, or for that matter Australia, than somewhere like Fiji.

Meanwhile Australia and New Zealand’s travel sanctions imposed against people who have connections with the regime have been very damaging to Fiji’s fabric. This is so because they’ve kept good, non-political people in Fiji from accepting positions on state-controlled boards vital to good governance. This should be an easy one to fix and lifting these sanctions would be a useful topic for discussion at today’s conference.

Efforts by Wellington and Canberra to choke off a big part of Fiji’s economy by halting UN use of Fijian peace-keepers, is short-sighted at best. Apart from providing a world class tourism product, the one thing Fiji has succeeded at is the supply of well-disciplined soldiers and security personnel to assist with regional security measures and world peace-keeping responsibilities. The record speaks for itself, from fighting side-by-side with Kiwis in the jungles of World War Two Bougainville, to the Malayan emergency, to the multinational force in the Sinai, UNIFIL in Lebanon, and a host of other international peace-keeping roles.

Looking back at 1987, measures imposed by Australia and New Zealand against Fiji, achieved no good at all. They hurt the country at a time when good friends would have been expected to lend a hand, and arguably relations between Fiji and Australia and New Zealand have never returned to the same highest levels of trust and friendship that existed before the events of that year. The friendship in question was forged over the preceding century in times of peace and war and if we are to honour what our forbears put in place, it’s high time for the powers that be in Wellington, Canberra and Suva to be more constructive.

In 1987, as in 2009, trade and investment in Fiji was hammered. Then as now, Fiji’s main trading relationship was with its southern neighbours, and because the aggrieved party in Fiji in 1987 was the Labour party, the trade union movement in Australia and New Zealand imposed sanctions on trade with Fiji. A good part of my time at Government House was spent working at ways to get those sanctions lifted.

Then as now, the tourist industry cut its rates to cope with the downturn that arose from negative media and government reports on Fiji. Then as now, people appeared in the media convincing Australians and New Zealanders it was immoral to spend holidays in Fiji as revenues raised would be used to support the coup perpetrators. Then as now, such advice gave little thought to the tens of thousands of Fiji citizens employed in the Fiji tourism industry who had nothing to do with the coups and whose ability to put bread on the table of their families would be stunted by such sanctions.

Then as now, the preservation of Fiji’s foreign reserves was the pressing economic issue and the Reserve Bank of Fiji turned to devaluation of the Fiji dollar as a quick fix, just as it has in 2009. Hollow logs were emptied of what they contained, but the spectre of no more hollow logs lay ahead. What does it mean when foreign reserves run out? It means government can’t pay its bills, it means public servants go unpaid and public services are severely curtailed, while imports are unaffordable.

If Fiji got to that juncture it would not be the first Pacific Island country to have become an essentially failed state. In spite of predictions that sanctions and other punitive measures will bring Fiji’s economy to its knees, I know few people who believe Fiji would be allowed to become a failed state. Sources of loan funds can be found by Fiji’s government to keep the country solvent, but there will be a price to pay in the long run for the nature of these loans and for the country’s poor economic management in the interim.

Again, I’d like to be unambivalent on this point. It should be glaringly obvious to the governments of Australia and New Zealand, that continuing measures to isolate Fiji and choke off its income will come home to roost not just on Fiji’s damaged economy, but on all of us in the South Pacific region.

I’d like to say a word or two on the Australia and New Zealand Fiji Business Councils as they have an important role to play during trying times such as these.

It’s hard for a small place like Fiji to make an impact in overseas markets, but it can be done. Look at the marketing brilliance that has taken Fiji Water to where it is in the world today and the entrepreneurial drive of men like the Solanki brothers and Padam Lala who created the Fiji garment export industry from scratch. The Fiji tourist industry can take a bow too. It established itself, climbing to the number one spot in the economy, in the face of ambivalent government support in its early days.

When I was consul-general of Fiji in Sydney between 1984 and 1986 I figured Fiji needed more friends in the Australian market, so I conceived of and built the Australia-Fiji Business Council, and prevailed on the Economic Development Board of Fiji to form a counter-part in Suva. The success of this endeavour led to me being hired as a consultant in 1988, to form the New Zealand-Fiji Business Council, evidence of whose on-going health today gives a true sense of reward.

Having sat on the executive boards of both councils, I can say that our respective governments have been welcome guests at the table to share with and hear the voice of commerce, principally because many of the resolutions of these conferences are prepared for the consideration of the relevant governments. But when these business councils were put together, it was never in our minds that they would be the lap-dogs of Canberra, Suva or Wellington. That is not to say they’ve become that, but I reinforce the point because some of our words today will filter back to the various capitals.

Something I learnt very clearly in 1987, was that relations between countries are much more than those between their respective governments. There are relationships of blood, of sport, of the internet, of ideas, of holidays and second homes, of religion and, yes, of commerce. Our business councils are meeting grounds for those involved in the commercial ties between our countries, gatherings at which we can celebrate our successes, discuss our difficulties, and shape our views and recommendations on what lies ahead.

Those who are engaged in cross-border business have to deal with similar sets of conditions and have a lot to learn from each other, therein the need for these councils. Their on-going existence proves they fulfil that need and are an affirmation of the importance of trade and investment between Fiji and its southern neighbours. So in these difficult times, my advice to the New Zealand-Fiji Business Council is to be boldly constructive in its field, to confront the problems and to be assertive and cooperative in their solution.

I’ve been asked to say something on the way ahead for Fiji. You may think having listened to some of what I’ve said today that I’m of the “Agree with the cause but not the method” school of thought, an agnostic line of thinking that gives comfort if not overt support to coup-installed regimes. I should point out that this school was prominent in Fiji in the aftermath of the coups of 1987, 2000 and 2006, even if its membership has utterly changed. I am not a member of that school. Having experienced first-hand the two coups d’état of 1987 and the rot of their results, I know in my bones there are better ways than military intervention to change governments and troublesome policies.

Neither am I in the camp of those whom one witty Fijian blogger describes as ‘The We Love Fiji So Much We Want to Destroy It From Overseas Front’. It goes without saying, you have a very different attitude to street violence when you or your family live on the street. I firmly believe that, as in 1987, the solutions to Fiji’s recalcitrant problems lie in an ongoing process of national dialogue towards reconciliation and reform that can only happen in Fiji.

The list of poor decisions by the current regime is long and I don’t need to list them here. There is no institution of importance in Fiji that has not been affected. But a lot of these poor decisions become understandable if you put yourself in the position of being the one who is sitting on top of the lid of a volatile political pot.

Let’s take as an example the regime’s media restrictions and their expulsion of foreign journalists. While those of us running businesses in Australia and New Zealand might quiver at the thought of taking on Rupert Murdoch’s empire, I assure you there’s no such fear in Fiji. People may say otherwise, but whether they’re from the Fijian nationalist side of the spectrum or from Labour’s loony left, there’s a demonstrated appetite for closing down foreign-owned media interests in Fiji, and the Fiji Times is first on their list. I’ve been following The Fiji Times since the days I first learnt to read and it brings me great sadness to think how perilously close narrow-mindedness has brought it to extinction.

At his first press conference on May 14th 1987, Rabuka gave the press a carte blanche to publish what they liked as long as their words did not inflame public opinion. The next day The Fiji Sun’s editorial read, ‘In one ill-conceived action the military has besmirched its proud record, each member has broken his oath of allegiance to our Sovereign Queen, and collectively descended to the level of a banana republic guerrilla force.’ Rabuka’s Council of Ministers met that morning and one of the first decisions it took was to shut down the newspapers and censor radio broadcasts.

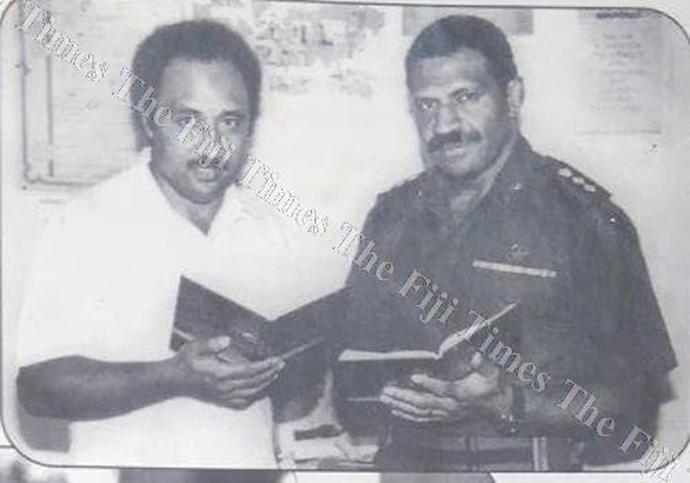

By the following week, with the governor-general’s executive authority over the country confirmed, the newspapers resumed publishing on May 21st. As to how that came about, I quote from Kava in the Blood, ‘At the meeting between Ratu Penaia and Rabuka, seated around the tanoa at Government House on the night of May 19th, Rabuka had agreed to withdraw soldiers from the newspapers’ premises at 8 am the following morning. It was agreed there would be no further censorship, but that I should meet with the general managers of the newspapers on May 20th to ‘give them good advice off the record’.’ That meeting was held and the domestic press remained free for the remainder of the governor-general’s tenure, giving space in its pages for the full spectrum of political opinion, including calls from the Taukei Movement for me to be kicked out of Government House.

The overseas media was less forgiving and it is interesting to consider the forces at play. For in those five months between the coups of 1987, at a time when the domestic media were fully supportive of the governor-general’s efforts to achieve national reconciliation, a loose consensus of views in the press of Australasia continued to belittle his position.

If I had one piece of advice for the current government in Fiji, it would be to work with the media, not against it. Foreign journalists need introductions to relevant people if they are going to write reports of value, reports that bring balance to what the overseas public perceives about Fiji. They need the freedom to talk openly to the people in the tourist facilities if they are to demonstrate the Fiji tourism product is as safe and pleasant as it ever was. The domestic press will regulate itself: there is a Fijian expression Kava ga e lala, e rogo levu, the empty vessels make the most noise, and it doesn’t take the public long to work out which are the empty cans.

The lesson I take from 1987 is that reconciliation of even the most passionate enemies is readily achievable through mediated dialogue. True Rabuka overthrew the governor-general’s accord, but the coup-leader himself came to see the error of his ways and led a national dialogue that resulted in the recently-rescinded 1997 constitution.

Today political leaders in Fiji are in their corners and there is no serious attempt being made to bring them into the middle of the room to get talking. To say this is hopeless cause because the Military Council won’t budge, is defeatist and probably dead wrong. If the carrot is enticing enough and if an accord is one that everyone can work with, the military will be on board. There is no shortage of intelligent people in the Fiji officer corps, and they know there are imperatives ahead that make a reconciliatory accord a better prospect than the current course.

In a dialogue process there has to be a structured programme that keeps the process on track, so that the inevitable boil-overs and walk-outs do not derail the process. There is an immediate reward for successful completion of the process, for as the Deuba Accord demonstrated, the moment the elected leaders of the deposed parliament endorse a new political plan, there can be no further objections from the international community and the aid taps turn back on with a flourish.

One of the outcomes of a mediated solution is that there is a list of agreed principles to guide the caretaker government through the intervening period between an accord and the next General Elections. Many of the goals of the present regime are laudable and would no doubt be built into those agreed principles, along with inputs from the political parties of the old parliament. Likewise a negotiated agreement might entail a mechanism whereby there would be no return to tyranny-of-the-majority-type legislation for short-term political gain. Central to such thinking is that governments of national unity by definition look after the interests of the nation as a whole, as opposed to the demonstrated propensity of governments elected by one community of a racially polarised country to look after the interests of their electoral community first.

In the end the responsibility for ending Fiji’s coup culture rests with the people of Fiji. If they want to live in peace in a prosperous country, they must embrace acceptance of a common destiny for all citizens of Fiji. It is up to them to reject hard-line political leaders who polarise their respective communities. It is up to them to allow a new generation of moderate leaders to lead. My mind goes back to independence leaders like Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau, who when they spoke, warmed the hearts of all citizens of Fiji regardless of race. Barack Obama is showing a better way to the world at large and it gives me no end of hope to see a good-hearted kailoma in the White House reaching for a higher ground for us all.

In conclusion, I’d like to say that the central lesson of 1987 for those of us wishing to make sense of Fiji in 2009, is that we have to keep open minds, that we have to be ever willing to engage in dialogue, to build bridges of understanding, to open closed doors, and that we have to believe in the proven effectiveness of mediated negotiation as the way forward. The political void was arguably broader in 1987 than it is today in Fiji, and that void was bridged by the Deuba Accord. The key was the creation of a structured dialogue process between leaders who were diametrically and passionately opposed to each other. If discussions failed today, they began again on the morrow with a fresh resolve to achieve what was best for the nation.

The fundament that I take from 1987 is one of hope and working each day, no matter what setbacks occur, towards a better outcome. There were people of moderate opinion then, at a time when public opinion was sorely polarised, and they were the bridge builders. We fostered those moderates and their zeal to heal the national wound.

There are many such people today in Fiji, people who are prepared to sit around the kava bowl and listen, and give good advice, and cajole, and give way and not take offence, and make useful suggestions, and do what they can to help the hardliners come to middle of the meeting ground. You can find them in the leadership of the churches, in the political parties, in the business sector, in the Council of Chiefs and in the Military Council. Our challenge is to support the efforts of those bridge-builders, to identify who they are and help them with resources wherever and whenever we can, for the good of Fiji and the good of our region.

The Godfather of Coups Sitiveni Rabuka claimed that Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau had pardoned him because of his 'exemplary behaviour'.

Well, we suppose he did set a very bad example of a coup,

which others followed after 1987

RABUKA: "“The only way to change the situation now is to throw this constitution out of the window.” These were the words of Sir Ratu Mara...Jim Sandy, the Chief of Staff, knew something would happen. He told me, his own words were, “Either you or the Commander have got to do this. I can’t do it: I’m kai loma, I’m a white European.”

"In 1987, you probably know the truth behind it. I was told, “The only way to change the situation now is to throw this constitution out of the window.” These were the words of Sir Ratu Mara...Jim Sandy, the Chief of Staff, knew something would happen. He told me, his own words were, “Either you or the Commander have got to do this. I can’t do it: I’m kai loma, I’m a white European.” And I didn’t say yes or no. I just said, “No, either you or the Commander [Ratu Epeli Nailatikau]. He’s got to do it. He is the Commander.” At that time, the Commander was going to go to Australia. After that discussion, nothing else took place. I quietly started doing what I was doing and training the people to be used, making sure we had enough ammunition in case we had to ward off any military counter-moves from Australia and New Zealand." - Sitiveni Rabuka, talking to Dr Sue Onslow in Suva on Thursday, 10th April 2014, for the Commonwealth Oral Histories Project

Onslow

Onslow SR: Sitiveni Rabuka (Respondent)

Transcript:

SO: This is Dr Sue Onslow talking to Mr Sitiveni Rabuka in Suva on Thursday, 10th April 2014. Sir, thank you very much indeed for agreeing to take part in this oral history project. I wonder if you could begin, please, by reflecting on your view of the Commonwealth, and the importance of the Commonwealth in the events of 1987 [i.e. the 14 May 1987 coup against Prime Minister Timoci Bavadra].

SR: Thank you very much, Sue. In 1987, you probably know the truth behind it. I was told, “The only way to change the situation now is to throw this constitution out of the window.” These were the words of Sir Ratu Mara.

SO: You were playing golf with Ratu Mara at this particular occasion.

SR: Yes. I caught up with him – they were in a group. I had made arrangements to meet with him. I got there late and when I caught up with them on the sixth tee, he said, “The only way to change the situation is to throw the constitution out of the window.” Before the fourteenth tee there is a villa where we stopped and had lunch, and that was also the end of the golf game. After lunch, I wanted to make sure that international relations were okay with him. He assured me they were okay. I said, “I’m worried about the reaction from Australia, New Zealand, America and the United Kingdom.” He said, “Leave those to me.”

So, the Commonwealth came out hard in the wake of the letter that His Excellency the Governor General at the time wrote to Buckingham Palace, admitting that his position as Governor General was no longer tenable. The Palace acknowledged. The Palace didn’t even ask him whether he would be able to re-exert his position as Commander in Chief and order me back to the barracks. So, when the reaction of the Commonwealth came out, I was surprised, but I also understood the position. It was the right position – the right stance to take – and I accepted it. But I was also committed to doing all I could at the time to restore relationships. I know that, at that time, the Vancouver Summit was approaching and we had sent as our special envoy the former Prime Minister Ratu Mara to go and start negotiations. While he was out there, he sensed that I was getting close to breaking the tie with the Realm and declaring Fiji a republic. I think he sent some desperate messages to try and stop me from declaring Fiji a republic, because he was going to try and get to Vancouver and lobby in the corridors of [the] Vancouver CHOGM.

I didn’t get the message from him in time. By the time I got it, it was too late and Ratu Sir Penaia had already written to say that his position was no longer tenable and offered his resignation as Her Majesty’s representative in Fiji.

[Editor’s Note: Fiji was declared a Republic on 7 October 1987. The Vancouver CHOGM was convened on 13 October 1987. Ratu Sir Penaia resigned on 15 October 1987.]

So, that is the Realm part of it. The Commonwealth is quite distinctly different from the Realm. The Commonwealth decided to deal with it as the Commonwealth ‘club’ and suspended us all. [Fiji was required to re-apply for membership of the Commonwealth following the Vancouver CHOGM]. I was committed to restoring the relationship. The process was not completed until July 1997, when we had restructured our Constitution and I was admitted back. I was invited to attend the CHOGM in Edinburgh and I went to that with my Leader of the Opposition, Adi Litia Cakobau, the great-granddaughter of the Chief that ceded Fiji to Great Britain in 1874, Ratu Seru Cakobau. On the way up to Edinburgh, I had called on Her Majesty. I think they were doing some work at the Palace, so we met at Clarence House and it was there that I asked if she would like to become Queen of Fiji. She said very simply, “Let it be the will of the people.” So, I offered a traditional apology – the presentation of a tabua [polished tooth of sperm whale] – and then, when we were talking, I asked her if she would agree for Fiji to approach her again to become our Queen. And she said, “Let it be the will of the people.”

That, in a nutshell, is the progress from suspension to re-admission [in the Commonwealth], and from seceding from the Realm – if we can use that word – and trying to re-establish the Monarchy in the Fiji situation. The response from the Monarch at the time was, “Let it be the will of the people.”

Since then – that was the 1997 CHOGM – we have not had any referendum or any further debate in parliament or out of parliament on whether we should re-establish our link with the Crown. It would be difficult to do that when we look at the composition of the population of Fiji at the time: there was a very strong Indo-Fijian component of the population. When you look at the Mahatma Gandhi revolution in India – where they wanted to have true independence, where the powers of the people of India were reposed in the people of India rather than reposed in the Crown of England – it would have been an uphill battle to try and convince the Indians in Fiji that we should go back into the Realm, because they had come out of the Realm. They had declared India a republic, and all the other republics at that time and before that time had broken away from a Monarchy and became republics where the people were the repository of the political authority in their own land. I didn’t consider the 1987 coup as a movement for true independence and true political autonomy, where our destiny was determined by the people of Fiji full stop. Although the Monarch was a ceremonial figure, it was still Her assent to the various legislative decisions [that mattered], which made it such that we were still under the authority of the Monarch of England.

SO: Sir, I have a number of questions, starting with, as you said, the golf game at Pacific Harbour. Was Ratu Mara playing with political colleagues, a close cohort of people, or just with personal friends?

SR: Only personal friends. They were not political. There was a businessman – a Samoan – and two other Samoans. One was the owner of the villa where we had the discussion, and one [was a] lawyer from Samoa. [Then there was] me and [another], a very close friend of Ratu Mara’s.

[Editor’s Note: Ratu Mara has confirmed that he was playing golf with Rabuka and other colleagues in May 1987, but he denies that they had discussions on a possible military coup. See for instance, the report in Asia Times, 22 March 2000]

SO: You said that you asked a very important question about Fiji’s international relations – that you were concerned about the attitude and reactions of Australia, New Zealand, the US and the UK. Did you leave that entirely to Ratu Mara? You said that he said, “Leave that to me.” I just wondered if you, personally, had become involved in any way with the international diplomacy around this particular issue?

SR: Never. Not at the time. I was just an ordinary soldier at the time.

SO: So, after the events of 14th May 1987, you weren’t aware of the discussions and contacts between the Palace and the Queen’s advisors in London with Ratu Sir Penaia in Government House?

SR: I was not aware of that, although that came out only in the writings of Sir Len Usher.

SO: You noted that Ratu Mara went to Vancouver to the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting to lobby privately. Was he accompanied by key advisors or was this a solo mission?

SR: I think it was a solo mission. He might have gone with an aide, because at the time I’d given him the privilege of keeping a close aide. We provided him with secretarial assistance when he was here.

SO: Ratu Mara later disclaimed any involvement in the military coup. Could you reflect on that? Do you think he was misremembering, or was this political expediency?

SR: I cannot say, but he wanted to sue me after John Sharpham published my biography with the Central Queensland University Press. [John Sharpham, Rabuka of Fiji: The Authorised Biography of Major-General Sitiveni Rabuka (Central Queensland University Press, 2000)]

SO: Yes, I’ve looked at that.

SR: He tried to sue me, and the CQU Press lawyers and my lawyers said, “Okay, we’ll see him in court,” and he withdrew.

SO: He withdrew the accusation?

SR: Right.

SO: It was a serious accusation, but this was a very serious matter.

You suggested that there was a groundswell of opinion within Fiji in September and October 1987 for Fiji to become a republic? Or was it that, once Ratu Penaia had submitted his resignation, this effectively became a fait accompli – he, as the Queen’s representative, had stepped down?

SR: Yes.

SO: But she still had it within her remit to appoint an alternative Governor General?

SR: Correct. She could have, and she could have exerted her authority: “You are my representative there. That is the role of Fiji’s military forces, the members of whom owe allegiance to Her Majesty, [and her] heirs and successors.” If they had tried that, I don’t know how I would have handled it. I might have just surrendered to the Palace, saying, “OK, bad exercise.”

SO: So, while all this was going on, were there other private representations being made to you from the Commonwealth, from the British military, from the British High Commissioner here? I’m just wondering about the process of contact that went on in any type of political challenge such as this.

SR: Only the High Commissioner met me – straight after that, after ten o’clock. And he said, “You know what you’re doing is wrong?” I said, “Yes.” “Are you not prepared to reconsider?” I said, “No.” I was quite strong in my responses to his questions, because I knew Ratu Mara was involved, and I assumed that he would be doing the international relations thing.

SO: Ratu Mara was certainly extremely well connected, and very highly regarded. So, after the resignation of Ratu Sir Penaia as Governor General on 15th October 1987 [he was appointed President of Fiji on 8th December] and before the whole discussion of the Commonwealth ‘club’ at Vancouver, were you the recipient of approaches from the Commonwealth, from Australia, from New Zealand, after Ratu Penaia’s resignation as Governor General? Once Fiji’s membership of the Commonwealth ‘lapsed’ at Vancouver, what was the process of re-engagement? How did the discreet diplomatic courtship continue?

SR: No. [There was] none at all.

SO: Okay. How about Australia and New Zealand within the South Pacific Forum arrangement?

SR: We were not in the Forum. They kicked us out of the Forum at the time. When we were admitted, we had started sending in our interim government and I was only a Cabinet Minister at that time. Ratu Mara was the Interim Prime Minister and the Forum very quickly accepted the status of things at that time. Dr Bavadra and his group were kept out. They were not even in the corridors. He tried to lobby for support in the Pacific at the time.

SO: Did you or your colleagues consider having a referendum on whether Fiji should become a republic? You said that there was no discussion in Parliament, but was there private discussion on this?

SR: No, there was no discussion in Parliament, but the legal advisors at the time said, “The only way to go now is to go all the way to being a republic, because you have sacked Her Majesty the Queen. If she comes back, then you are all liable for treason against Her Majesty.” So, the only way to put an end to that is to just say, “This is no longer Her Majesty’s Government. It’s no longer Her Majesty’s territory of Fiji. It is now a republic.”

SO: So, as you say, the military forces then swore allegiance to the Republic of Fiji, because otherwise they would be in a treasonable position.

SR: Correct. So, we changed it. The Court of the Republic of Fiji arrived and Her Majesty’s Chief Justice and [other royal titles] – all those things had to be cleaned up. The only way to really have it clean was to have complete severance of any ties with Her Majesty’s authority.

SO: So, between this particular point in 1987 and your description of July 1997, when Fiji was included back in the Commonwealth and after your meeting with Her Majesty at Clarence House on your way to the Edinburgh CHOGM, which international relationships became of key importance to Fiji in this particular time? Fiji was expelled from the Commonwealth, and this was a time when Fiji’s trade in the region – the South East Asian region – and with the European Union started to assume far greater significance than those trade relations with a Commonwealth dimension.

SR: Yes, we started to ‘Look North’ and started looking at alternatives to our traditional trading partners and aid partners. So, the Commonwealth hold on Fiji became less, although we had bilateral agreements with Australia and New Zealand. We had the South Pacific area trade agreements, SPARTECA [South Pacific Regional Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement], and we developed those. I think people at that time were more pragmatic and did alright: “We don’t like your politics, but we like your products so we’ll keep trading and we want you to buy ours.” So, we were a significant importer of Australian goods and New Zealand foods. We were totally dependent on imported fuel, so we had to have trade. I think it was in their best interests to develop new relationships. But when Bainimarama came in in 2006, we leaned more on China and more on Asia. India came back in and has given us some support, we think – we would like to believe. And we find ourselves now in a very bad debt situation.

But going back to Fiji’s suspension from the councils of the Commonwealth, I think the time now is for the Commonwealth to rethink its ‘club membership’ rule. Rather than having uniform political values, you just have the common history as a basis and continue to try and influence the members in the area of good governance, rather than breaking off all relationships altogether. It would be better to try and get in there and talk to them, rather than putting the world down.

SO: This was the original argument of Secretary General Chief Emeka Anyaoku with the establishment at the Harare Declaration in 1991: to try to influence and encourage members on issues of good governance. The creation of the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group and the expansion of its remit since 1995 have added to this. But you feel there should be a shift back to a voluntary association of states with a shared history and shared political linkages, supporting and recognising diversity?

SR: Well, we should continue to recognise our diversity on good governance and values and things like that. We should not sever our ties; we should continue to try and improve, instead of cutting off somebody. Work with them, go forward with them, cooperate with them, [and] try and get them out of the situation they are in. Unfortunately, my coup and the current situation we’re in are different. Mine was linked to a political party – the Alliance Party of Ratu Mara – and the Fijian people. This one is purely military. So, I was not the Commander [in 1987].

SO: You were not the Commander of your coups in 1987?

SR: No. I cannot claim that I took the Army.

SO: How did you see your position then?

SR: I was number three in the Army, and I took a group of people to capture the government.

SO: But your superiors – the number one and number two in the Fijian Army – did you have political discussion with them? Or was this an autonomous action by you and middle–ranking officers?

SR: Jim Sandy, the Chief of Staff, knew something would happen. He told me, his own words were, “Either you or the Commander have got to do this. I can’t do it: I’m kai loma, I’m a white European.” And I didn’t say yes or no. I just said, “No, either you or the Commander [Ratu Epeli Nailatikau]. He’s got to do it. He is the Commander.” At that time, the Commander was going to go to Australia. After that discussion, nothing else took place. I quietly started doing what I was doing and training the people to be used, making sure we had enough ammunition in case we had to ward off any military counter-moves from Australia and New Zealand.

SO: Were you expecting that?

SR: No, I was not, but I just wanted to make sure that we were equipped. If they were going to evacuate their own citizens, there was a risk of some people being over-exuberant in the execution of their duties or in the execution of the defence, which could very easily turn into an ugly confrontation of military personnel. At the time, we had almost no ammunition. I had to make sure that fresh supply was here in time for that. So, I got in touch with the agent who was selling ammunition to Fiji to see if we could buy from Singapore. We bought some ammunition from Singapore, put [it] on a naval boat which was not yet…

SO: Excuse me, Sir, were these contacts with the Singapore military? Or was this a private arrangement?

SR: No, a private agent came to us and took orders for ammunition from the suppliers.

SO: So, you were putting contingency plans in place?

SR: Yes.

SO: Were you concerned particularly about an Indian response? An international Indian response?

SR: Yes, I was, but I was also aware [of] the Indian design in Fiji. They wanted me to be Commander in 1980, 1981. I was interviewed by [the-then] Indian High Commissioner to Fiji, and she was trying to push strongly for me to become the Commander because I would sympathise with the Indian design in the Pacific, being Indian-trained. I’m a graduate of the Indian Staff College and at that time I was the only one that had a university degree. I had been given an award by the University of Madras as part of the Defence Services Staff College course.

SO: So, this was part of an Indian approach to the Pacific region – offering trade and training?

SR: Yes, and shore bases. They were looking for shore bases, because they couldn’t get a foothold in Perth in Western Australia. They thought it would be a better opportunity to hop over Australia and get something in Fiji that would isolate Australia and New Zealand, and effectively put India into the Pacific.

SO: Did this particular approach in 1980–81 surprise you?

SR: It didn’t even rub my ego. I was always bent on making the Army my professional career. I understood the leadership succession plans that might have been existing at the time, although I was not happy with Ratu Epeli Nailatikau coming back from the Fijian civil service into the Army and pushing everybody down in the promotion list.

SO: So, fast forward to 1987, against this background of the Indian High Commissioner’s approach and your training at the Indian Staff College, you had a particular perception of an Indian presence in the Pacific and the political developments here in Fiji with the May 1987 election. Were you concerned about potential elements within the Indian Government or in the Indian Army intervening in this situation?

SR: I knew it could happen, but it would be very small scale, small cells, and more on the psychological side. They would try and convert us, psychologically. I expected that to happen, but if Australia and New Zealand were still there, it would be difficult for them logistically to come into the Pacific. So, Australia and New Zealand were both a threat and an obstacle for a bigger threat.

SO: So, Australia and New Zealand would potentially pressure you, but they were also a barrier, as you conceived it?

SR: That’s right.

SO: I have heard that there were rumours of arm shipments going into Lautoka at this particular point.

SR: Yes, that was later – about 1989-90 – when there was a shipment that finally got to Lautoka and there were others which were not spotted. However, they were on the Australian radar and the information came through Australia which enabled us to go and look [for the shipment]. We found some dilapidated arms and ammunition on some Muslim farms in the west.

SO: How far did you attribute these particular incidents to Indian concern about Sri Lanka? Did you put it in a wider Indian context?

SR: I’m playing golf on Saturday with TP Sreenivasan. who was Indian High Commissioner to Fiji at the time, so I’m going to ask him whether there was really a fundraising effort in India House to pay for this shipment which Kahan sent. Kahan was the Fiji citizen who ran away when his pyramid scheme was uncovered. He ran away and lived in England. Yes, he’s the one that was supposed to have been collecting money from [Adnan] Khashoggi and company, and secured some sources. But then, I am aware of what international arms agents do. They would have got rubbish arms and ammunition which they would not have even checked, and the people would have gotten the money and run, knowing that their buyers were buying rubbish. And the buyers would be selling on that stuff to their rebel leaders, wherever they are. It’s the same whether it’s the Sandinistas, whether it’s Central Africa or the Pacific; it would be the same. The people would end up with dilapidated arms and ammunition and probably lose one in ten for bad ammunition backfiring and blowing your eyes out.

SO: So, it was more of a political gesture than a shipment that would lead to the radical overthrow of a government…

SR: Yes.

SO: After Fiji had been expelled from the councils of the Commonwealth, how far did you push to repair the rupture?

SR: I didn’t.

SO: What of Fiji’s relationship with Australia and New Zealand, though? Precisely because of your perception of the barrier they provided against Indian influence in the Pacific…

SR: We were still under the 1990 constitution, which people didn’t like. After the election, the very first Foreign Ministers meeting was held in Honiara. That was where I met Paul Keating. But although it was based on a bad constitution according to international assessments, it was the will of the people. People were back in Parliament, representing people, so Keating immediately invited me for a state visit to Australia and that was the restoration of that. That was 1992. So, from 1987 to 1992, there was no direct contact, although we had exchanges [between] our diplomats. They were called Ambassadors rather than High Commissioners until we were restored to the Commonwealth. Then we had High Commissioners.

SO: How badly was Fiji affected by the severance of international aid following expulsion from the Commonwealth?

SR: We did have to readjust. We had to be very prudent about our fiscal and financial management. It was a very good time for us because we were very prudent in our management of debt and in our budget. Although we were not answerable to the people, we knew where we were going. We knew if we were not elected in the next election, we would be there paying the tax, as taxpayers.

SO: So, it was a question of getting your macroeconomic policies right? Your foreign exchange earnings came principally from tourism, the key sector for Fiji’s economy, because sugar had started to diminish dramatically by this particular point.

SR: Yes. At that time the Sugar Land Tenancy Agreement was up for review anyway. [It was] up for closure because there was no renewal clause in any of the acts that governed the Landlord and Tenant Agreement.

SO: How much did Ratu Mara stay involved in politics, despite having formally stepped down as interim Prime Minister?

SR: Internationally, he didn’t play a very active role. I think he lost his Privy Council membership – whether they do [lose it] or they’re just not invited back to the club, I don’t know which is the case. But he was hurt by the sudden rise to prominence of an unknown soldier. When his choice for Prime Minister in the 1992 election did not become Prime Minister, he had become my number one political obstacle. He worked with the other political parties and tried to spread his influence so that I could be ousted. He supported his daughter’s candidacy with the Methodist-based Christian party in 1999.

SO: Adi Koila Nailatikau?

SR: Adi Koila, yes. And that split the Fijian vote. That cost us very dearly. We only won eight of the seats. My coalition partner – they were not a coalition partner at the time – but the National Federation Party was demolished. It didn’t get one single seat.

SO: Was the intensity of political debate and political infighting affecting Fiji’s foreign relations?

SR: Yes, because most of the leaders at the time were still friends of the Alliance Party and they wanted Ratu Mara and the post-coup plan to be the national plan of Fiji. The new leadership came up with me and the other politicians and subordinates in the Alliance government took on a new direction. I think they were not very comfortable. I think his biggest hurdle came when Dr Mahathir openly supported me.

SO: I was just thinking that, given Ratu Mara’s standing as a leading Commonwealth spokesperson for the Pacific from 1970 onwards into the 1980s, he would have had extraordinarily good personal links with other Commonwealth leaders.

SR: But he could have used that. He could have volunteered to use that contact, but he didn’t. From 1987 to 1992, I think he played on that and got a lot of things going because of his personal rapport with the international leaders. So, I must give him credit for our passage from coup to election: 1987 to 1992. It was after the election that I think he wanted to re-exert his brand of leadership into the new Republic of Fiji. That was what resulted – whether he worked for it or not – but it resulted in the split among the Fijian vote.

SO: In terms of legal advice for the new Fiji constitution in the 1990s, did you draw entirely on Fiji legal opinion or did you go outside?

SR: We got Professor Bloustein of the University of New Jersey who came and worked with the report that was brought together by the Sir John Falvey [Constitutional Review] Committee, and after that it was refined. He did some work on it and [Paul] Manueli went around and refined that. That became the base for the 1990 constitution.

SO: Was Ratu Mara supportive of this political process for constitution building?

SR: No, he was just…. While he was head of the Cabinet as Prime Minister; he put those things in place, yes.

SO: So, in the 1990s, Fiji’s foreign relations drive was ‘Look North’. From what you have said, it seems the Commonwealth hold was diminishing. You emphasise particularly the South Pacific angle. How important was the goal of readmission into the Councils of the Commonwealth for your government? Or was this in fact very low down the list of priorities?

SR: It was low down. For us, the restoration of relationships with Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia and Asia were more important – for me, at the time, as Prime Minister. Even during the coup era, from 1987 to 1992, as a Cabinet member, I was more concerned with the immediate area of interest rather that the wider Commonwealth interest.

SO: Sir, on the events of George Speight’s coup in 2000, were you in any way consulted or engaged by outside Commonwealth observers? Fiji had, after all, been readmitted to the Commonwealth in 1997.

SR: No, there was none, although at that time I was working as the special envoy for peace in the Solomons. Chief Anyaoku had put me there and my deputy was Dr Ade Adefuye, a Nigerian. We worked together in the Solomons. While we were still continuing our work, the 2000 coup happened. I don’t know whether the Commonwealth Secretariat was wrongly informed or deliberately wrongly informed that I might have been involved. I was not invited to go back [to the Solomons] after that, but already we had laid down the ground rules. We had negotiated the ceasefire and the negotiations for peace which formed the basis for ongoing work that resulted in RAMSI, the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands, in 2003.

SO: Sir, please, could I ask you how you came to be Chief Anyaoku’s special envoy?

SR: I was asked when my party lost the election. I won my seat, with the biggest number of votes in the whole election, but two members of my own party – the Fiji Political Party, also known as the SVT, Soqosoqo ni Vakavulewa ni Taukei – came to me and said, “You have to take personal responsibility for this and resign as party leader,” and I said, “Okay”. So, I resigned as party leader, and one of them became party leader and Leader of the Opposition. I was Chairman of the Provincial Council and Chairman of the Council of Chiefs when our High Commissioner in London called to say that the Commonwealth Secretariat would like to offer me this job as a special envoy. There was no pay in it. I said, “Okay, that’s fine,” but when I went to the Solomons I had some problems because the people of Malaita saw me as a nationalist. The problems in Guadalcanal at the time – in Honiara, particularly – was between the indigenous people of Honiara and Guadalcanal, and the outsiders from Malaita. The Malaitans were stronger and they were in government in most of the top positions. They probably saw me as naturally favouring the indigenous Guadalcanali people.

SO: How much prior briefing did you have before you went to Honiara?

SR: I didn’t have any briefing. I went there and tried to find out what was happening.

SO: So, that’s where you met Dr Adefuye from the Secretariat? How well was Dr Adefuye briefed?

SR: He was informed about the basic issues. We had a discussion and I said, “Well, in that case, let’s go.” He said, “Where?” “We are going to see the rebels.” He panicked. Our contact was the Roman Catholic Archbishop who took us to the end of the civilised route.

SO: The end of the paved road?

SR: Well, not just the paved road, [but] to where they had the police influence. After that, it was ‘no law’ territory. So, we went in and we had to walk back out to our little Suzuki. We went in and suddenly they just came out of the trees and over the ground. They stood there with their carbines from the Second World War that were left behind by the British forces. I knew they wouldn’t fire; I knew they didn’t have any ammunition. If they had the right ammunition, they wouldn’t be able to go into the bore because they were all rusty.

SO: Dr Adefuye didn’t know that! [Laughter]

SR: No, he was very, very scared. I felt sorry for him. [The rebels] came up. I had with me a bundle of kava. When they came, I told Ade, “Sit down.” So, we all sat down and I presented the kava in Fijian. There was somebody there who received it in English and pidgin, and then after that they brought in a big pile of betel nut and made the reciprocal presentation. So, we started talking. That was it. I did a Fijian custom; they did their own custom.

SO: Yes, but you were able to communicate enough.

SR: Yes, in English. Most of them spoke English well enough. Even their pidgin we could follow, but they spoke to us in English.

SO: So, there was enough of a hierarchy there – it was not a rabble militia, there was somebody that you could negotiate with?

SR: Yes, the leaders were university-trained: University of the South Pacific (USP) trained and Fulton College trained. Both had trained in Fiji. That was the beginning. I went then to the rebel stronghold; I also went to Malaita and spoke to them, and then called them both together to Central Province, another neutral island where they all came for a discussion. Then we drew up the Peace Accord.

SO: So, this was very much personal negotiations by yourself and Dr Adefuye? Communication with Chief Anyaoku at Marlborough House would have been non-existent.

SR: No, that’s right, but there was the Commonwealth Youth Programme. We used the Youth Programme as our base office and used their communications and secretarial support. But we did a lot of the work. Adefuye must take a lot of credit because he just persisted and he didn’t know the Pacific. I knew the Pacific. He was surprised there was no similarity in the African – particularly Nigerian – way of doing things. But he recognised the custom side of it. He recognised the tribal and custom side.

SO: So, a wider Melanesian world?

SR: Yes.

SO: Also, you had been a military commander who had become a democrat yourself: an elected Prime Minister. So, you had a unique authority to discuss with these people who were trying to use military force to achieve political goals.

SR: They also knew me, as they called me ‘General’. In fact, one baby was born when I was there and his first name is ‘General’ [and] second name is ‘Rabuka’. [Laughter] When my cousin went back to the Solomons last month, I said, “Hey, go to this village…!”

SO: “Ask for my yaca [namesake]!” [Laughter]

SR: Yeah, “My yaca is there.” “What’s his name?” “General.” “That’s not your name!” “Well, that’s his name. He is my yaca.”

SO: So, how long was this Special Envoy trip?

SR: From 1999 to 2000 – to the coup. About a year. We just went there and Ade would say, “Okay, see you in Honiara next week.” Okay, go back, and we’d continue. He’d go back with our findings and our drafts to the Secretariat and then come back.

SO: So, you were based in Honiara for a year?

SR: Yes.

SO: Sir, did you get credit for this? This was an important Peace Accord that you were…

SR: I think they tried to down play it. Straight after that, the Labour government was in power here. They didn’t even acknowledge any of the things I was doing. I wasn’t even allowed to use the VIP lounge in the airport! Not that I missed it… I was comfortable just talking to the public in the public lounges.

SO: But this was Fiji contributing to international peace and conflict mediation.

SR: Yes.

SO: Sir, after the events of 2000, Fiji was again suspended from the Commonwealth – in 2006, following the coup led by Frank Bainimarama.

SR: No, 2006 was different: after 2000, there was no suspension.

SO: No, but there was another coup in 2006.

SR: There was another one in 2006, which was the only military coup we have had because the Commander had said to the government, “We don’t like what you’re doing. If you don’t change, we will take over.” Which he did, and that was a military coup. In our case, it was just a group of soldiers and me, and then I spoke to the Army that day and said, “We have done this. Anybody who doesn’t agree is prepared to leave. I have now replaced the Commander; I’ve taken over as Commander.” There were two coups: one against the Commander and one against the government. I first had to claim and then get myself accepted as the Commander of the military. The soldiers, they all came back – apart from four who had to take some leave. We gave them leave; one of them asked for an extension of leave to deal with his own conscience, and then came back. I gave them the choice: “Either follow your conscience and your oath of allegiance. If you cannot handle this, you’re free to leave.” But only four left for a while and then came back. Then I was installed by them as Commander.

SO: Sir, I’ve done research into the role of the Army and the security services in Zimbabwe and the extent to which that they became politicised, particularly from 1999–2000. How far do you think that there’s been a comparable process of politicisation of the Army – and a core group within the Army – in Fiji politics now?

SR: Yes, from 2006 I think we became very, very politicised. It was then [that] the political aspirations of our current Prime Minister…. Because he said, “You’re not running Fiji politics properly. We’re going to do it right.” So, they took over from Laisenia Qarase in 2006, and because he had a design – the proper design for the governance of Fiji, not the one that was being followed by the elected government – he now wants to run so that he can continue his programme. That’s why he’s running for this election.

SO: But he’s formed a political party, Fiji First, and he’s taking part in the September general election.

SR: He’s looking for support now.

SO: I read the reports in this morning’s paper. But isn’t there a potential problem if there has been a politicisation within the medium ranks of the security forces? If they use military means to ‘correct’ the democratic process? Is that habit forming?

SR: Yes.

SO: So, it may be difficult to get the troops to stay in the barracks?

SR: That’s right. Our only opportunity now is to convince the current leader that, “You are the one that can stop this. You stand firm and tell the politicians, ‘Go to hell’, if they come back to you. You’re going to sort it out in Parliament. ‘I’m not going to support any of you or you – opposition or government or anybody else. We’re going to do our duty. We are going to support the police in law and order breakdown.’”

SO: Have you been contacted by any people from the Melanesian Spearhead Group, from the Pacific Island Forum, for your insights or for your contribution to make sure the democratic process is indeed followed in these elections?

SR: No.

SO: Sir, you’ve continued to take an active role in politics?

SR: I’m standing for election, but nobody has come to me to ask for my views. If they had come, I wouldn’t have tried to go back. I would have tried to solve or contribute to the solving of our political problems from outside Parliament, because I’ve not been asked to do that. I’m going to Parliament and [will] work inside Parliament as a representative of the people.

SO: Sir, can I ask you about Fiji’s current international relations? Australia and New Zealand are still particularly important as significant members within the Pacific region…

SR: The current leadership would like to say no, but that is wrong. They will remain important players in this part of the world.

SO: What of China?

SR: China is getting very big, but who are the Lapita people? [Laughter] People think that this is newly emerging – China from Asia. But the Lapita people, who were here before the Melanesians arrived, were very much Asiatic. When people dig up old sites and you look at the discoveries, they find skeletons of people who are not Melanesians; [they are] not like me. They are more like Chin Peng or somebody. I will send you the address I made to the Otago University in Dunedin.

SO: So, they think the first settlers in Fiji were the Lapita people?

SR: Yes. They were small; they were more like Micronesians and Asians. The indigenous Asians, indigenous Chinese… Some tribes remain in Taiwan.

SO: Sir, please could I ask you about the contemporary relationship between Fiji, the People’s Republic of China, and with Taiwan. I know it has been controversial.

SR: Yes.

SO: As China follows a ‘One China’ policy, if Fiji was trying to push forward its relations with Taipei, that would be problematic for your relationship with Beijing.

SR: Yes, well, we have diplomatic relations with Beijing and we have a people-to-people relationship or technical relationship with the Republic of China on Taiwan. During my time, we managed to keep that going well. In our official visits, we would go to Japan and then China, and then go to Malaysia and then Taiwan. As long as you’re not travelling directly from China to Taiwan or Taiwan to China: you need to have another intermediate port.

SO: Sir, I know that your embassy in Beijing is your largest overseas mission. Fiji only has two people in London, and you’ve got twenty in Beijing. It has been said that China’s particular investment in Fiji also helps to remove any international encouragement or international pressure for democratisation. Would you say that’s a fair comment, or not?

SR: That’s a fair comment, but those who are encouraging that or going along with it don’t realise it. China’s main interest is China.

SO: Yes, it is indeed. Beijing’s policy is hard–headed and pragmatic. So, do you think that the lack of conditionalities in Chinese investment has been slowing down the democratisation process?

SR: Yes, it has. It has slowed down the democratisation programme and progress because we said, “To hell with democracy, we are doing well. We’re doing well with our new friends.” So, it has probably been the biggest agent for the slow progress.

SO: But if there is an American competition with China, pushing FDI…

SR: It’s still the same.

SO: Okay, so there seems to be geo-strategic contestation between China and the USA over Fiji, but you are saying the policy and actions of both, in fact, undercut democratisation?

SR: Yes. And we still overplay our self-image. We think that we’re too important.

SO: When I lived here in Fiji in the late 1970s, it was regarded – and saw itself – as ‘the hub of the Pacific’!

SR: [Laughter] Well, the time will come when people will say, “Okay, do your own thing, we’ll do our own thing and we’ll see how far we can go.”

SO: Where is most of your fuel coming from now?

SR: Through Australia.

SO: Is that a strategic pinch point for you, because it makes Fiji susceptible to Australian political pressure for democratization?

SR: No, because we can source fuel elsewhere. The fuel companies buy their [fuel] from anywhere, and they will continue to do that. So, it doesn’t have to come through Australia. It could come through Asia, Papua New Guinea… Papua New Guinea can be the staging port for trade.

SO: Sir, going forward, how much importance would you attach to Fiji being welcomed back into the Commonwealth?

SR: Not at the moment. I think it’s no longer a very significant victory. Although, I’m part of the Fiji Amateur Sports Organisation and National Olympic Committee (FASONOC) and being allowed to participate in the next Commonwealth Games is a good thing for our sports people. But our readmission into the Commonwealth? The people will like and will enjoy it, but the government will not treat it as a big deal. But it is important, because of the moral and cultural interaction we will have with people of similar histories.

SO: How important are these sporting links for keeping the idea of a Commonwealth alive for Fiji? In terms of rugby and participation in the Commonwealth Games?

SR: They are important [for] the promotion of sports. It’s a very credible international competition where we can really say, “Okay, we’re going to go to the Commonwealth Games.” Now, we have a gold in the Pacific Games: so what? You look at the times of our gold medallists: “You wouldn’t have qualified for the Commonwealth, and you are our best athletes?” So, the Commonwealth Games are a step-up for the sports people of Fiji. If you want to play there, then you have to improve your facilities and improve the technical knowledge in Fiji. So, you expand it from the track to the technical people – coaching, the high performance unit technicians who come. At the moment, they’re mostly from England and Australia.

SO: You had mentioned the Commonwealth Youth Programme being very important to support your special envoy position in the Solomon Islands. How much do you think that the young people of Fiji connect with the idea of the Commonwealth of Peoples? The Commonwealth has changed from its inter-governmental aspect in 1987 to a very different entity now.

SR: Yes. I don’t think they really understand how important it is. The significance or the importance [of the Commonwealth] really is diminishing; the longer the isolation [of Fiji], the more difficult the restoration. I’ve said that many times before. While we are kept behind this wall of restrictions, our young people have developed their own perception of the international youth community. Now you go to our university [and] you’re internationally marketable: you can go and work anywhere. The border controls are not as strict, unless you are carrying weapons, narcotics and things like that. If you have a clean record, you can go anywhere. If you have a good academic record, you can work anywhere. The old Youth Programme for the Commonwealth – the old Colombo Plan and things – are no longer as applicable now as they were at the time.

SO: Are there civil society organisations from the Commonwealth which are active here, that you know of?

SR: They are no longer known as ‘Commonwealth’ civil society organisations, but they’re mostly England-based or Australia-based, the civil society groups that are here, yes. They are Commonwealth-country based.

SO: Sir, how far do you think the Queen has been critical to the survival of the Commonwealth?

SR: I think very, very, very critical. A lot of people don’t care so much about the Commonwealth as they do about Her Majesty. I think [that] if we have a new monarch who wasn’t there with our fathers during the War, then I think the significance will very quickly diminish.

SO: Sir, thank you very much indeed for answering my questions.

Friday, May 14, 2010

By Sam Thompson

Democracy as we knew it in Fiji ended on the stroke of 10 on May 14, 1987.

The chiming of the clock at Government buildings was the signal for the then Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka and his men, to storm parliament and kidnap the democratically elected Government of Dr Timoci Bavadra.

Every journalist has a defining moment in their career.

My claim to fame was this one. I broke the news to the world.

But I almost missed out on being a witness to one of the most momentous moments that changed the course of Fiji’s history.

At the time I was a cocky 26-year-old editor of Fiji’s first commercial radio station FM96.

I say that because we were redefining radio from the drab drivel of the government run stations at the time.

We pushed the boundaries by starting hourly news bulletins with a three man new team, against the vast resources of the Government broadcaster.

They said it couldn’t be done because Fiji was too small and many on the sideline were watching, expecting us to fall flat on our faces.

With this back drop of having much to prove, I was sitting at my desk on that fateful day exploring options of how to generate fresh news for the top of the hour.

The tedium of a parliamentary session, trying to make sense of what out elected representatives were saying was unappealing, but I decided was a necessary evil.

So I ended up at the press gallery, bored silly, and because I had skipped breakfast hunger pains were setting in.

This was the pre-mobile phone era where land lines were fiercely guarded and faxes ruled.

There was just one phone next to the press gallery where Hansard recording were taking place.

At 10am when the clock started chiming, I decided I had enough and got up to leave, when I noticed Rabuka striding through the parliamentary chamber towards the Speaker.

My curiosity peaked and I decided breakfast could wait.

Rabuka was not in uniform, he was dressed smartly, coat and tie and a sulu, no indication of what’s to come.

Shortly after balaclava clad men, dressed in army fatigues, brandishing pistols barged into parliament positioned themselves behind Government MPs.

I remember thinking this is an unusual exercise for the army to conduct, but than my journalistic instincts kicked in and I started counting heads and observing details.

Among those were Rabuka instructing Government parliamentarians to follow his men out of parliament.

Prime Minister Dr Timoci Bavadra leaning back in his chair, rolling his eyes upwards, slapping his table with both hand, pushing himself up in defiance.

A soldier, placing a gun in his back and ordering him to lead the way out of parliament.

Other Government MPs roughly pulled out of their seats and shoved along at gun point, some stumbling, others leaning on each other for support, in confusion.

Fiji Broadcasting Corporation journalist Francis Herman (later became chief executive of FBC) and I looked at each other and it dawned at us at the same time that this is a coup.

Both of us scrambled for the only phone. He got there first.

The nearest phone for me was the Ministry of Information building next door.

I went charging down the gallery stairs. The old parliamentary entrance had bat wing doors, like the cowboy movies.

I burst through that and came to a screeching halt with an AK 42 riffle in my stomach and a balaclava clad soldier at the end of it wanting to know what the #@#* I was doing.

Like any B grade movie I immediately put my hand up, shaking my note pad, as if that was going to be any help, shouting “I’m a reporter, I’m a reporter”.

He obviously had more pressing issues to deal with and told me to “get the #@#* out of here”.

I didn’t need to be told twice.

I raced into the Ministry of information building, shouting give me a phone, any phone now.

The Director of Information at that time was Peter Thompson. He wanted to know what the urgency was. While dialling the radio station, I said there had been a coup. He and a few others around at the time laughed and said yeah right.

By that time I had been put through to the studio, I told the announcer to fade the music with breaking news.

I started my report saying there has been a military take over and gave details of Rabuka and his men storming parliament and taking Government MP’s hostage.

Peter Thompson heard the report in stunned silence and finally said “well they are going to be here wanting to put out a press release”.

One of the Information Ministry reporters grabbed the phone from me and said I can’t use it anymore.

Francis Herman should have broken the biggest story in Fiji’s history. He later told me he was trying to convince his superiors that there had been a coup, but no one would believe him.

I had no such problems, I was the editor, no one was going to argue with me.

So I waited for the first news release by Rabuka, officially telling Fiji citizens, their lives had changed for ever.

By that time the building was surrounded by armed soldiers.

I grabbed the first the copy out of the printer and jumped through a window, my only way out of the building.

I ran to the road to flag down a car to get to the radio station as soon as possible, to get the official statement to air.

The first vehicle to come along was a police van which I flagged down. Luckily I knew the officers from my days doing the police round.

They said hop in and they will drop me and started asking what was the hurry .

I said there had been coup.

Their response “Oh yeah, so what happened”.

I said “you know a coup, don’t know what the hell’s going to happen now”

They looked at me blankly so I explained to them the military has taken over, guns are involved, elected government is under arrest.

It suddenly dawned on them what a coup was, they both looked at each other and said to me “we can’t take you to FM96 anymore we’ll drop you at the nearest taxi stand”.

By that time the military had stormed the Fiji Sun, The Fiji Time and FBC and shut them down.

FM 96 was the new kid on the block, they forgot about us when they planned the coup.

When I arrived at the station there was no soldier in sight.

I got Rabuka’s official statement that he had taken over the country to air and had a field day getting reactions.

Emotional clips of Bavadra’s wife and relatives of other MP’s, Opposition sentiments to the coup. It was picked up by the wire service.

The news had got out. It took the military four hours to realise people knew what was going on because they had tuned into FM96.

By that time I had done numerous interviews with overseas news organisations including Radio New Zealand, Radio Australia, BBC and Voice of America.

* Sam Thompson now lives in Auckland, and works for NewstalkZB radio station