"The reputation of Australia and New Zealand has also suffered greatly. Both these countries are key players in the region and important benefactors of the regional university and other institutions. Both showed a strange, unaccustomed lack of courage and leadership in the USP saga. They saw the tussle between Prof Ahluwalia and the key senior players of the USP administration as a problem between individuals rather than as a manifestation of a deeper structural problem, which is Fiji’s determination to have a lion’s share of say in the management and running of the university. Instead of demanding transparent accountability from those implicated in Prof Ahluwalia’s investigation, they bent over backwards to accommodate Fiji or, at best, to look the other way. Australia particularly is currying favour with Fiji for larger strategic reasons of its own and is therefore reluctant to be forthright in its responsibilities. China’s presence in the South Pacific region looms large in Australia’s thinking. It mistakenly thinks that by supporting Fiji, they might be able to restrain Fiji’s current China enthusiasm. Fiji, for its part, is acutely aware of the power of the China card it has in its hands and will play it to its maximum advantage irrespective of its broader regional implications. The way Australia and New Zealand have behaved during the USP saga has not been unnoticed in the region. It has damaged their own reputation in places where they sought to assert their influence." Professor Brij Lal

Brij Lal

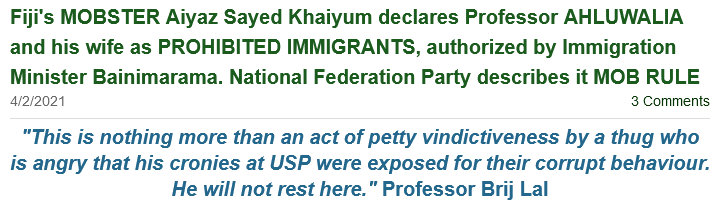

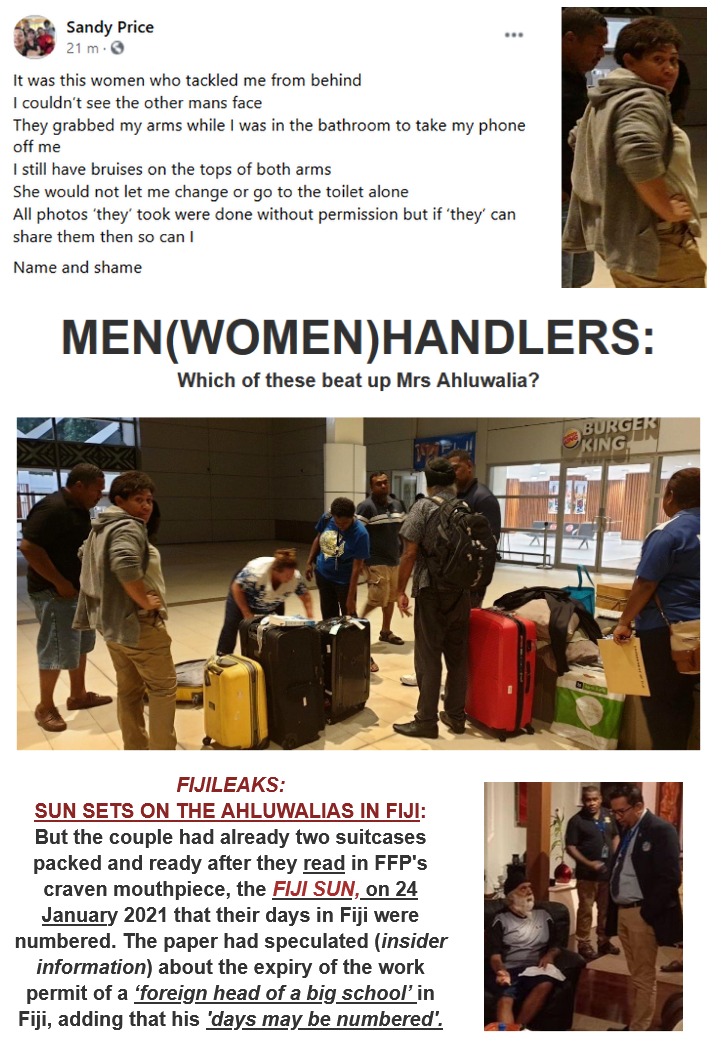

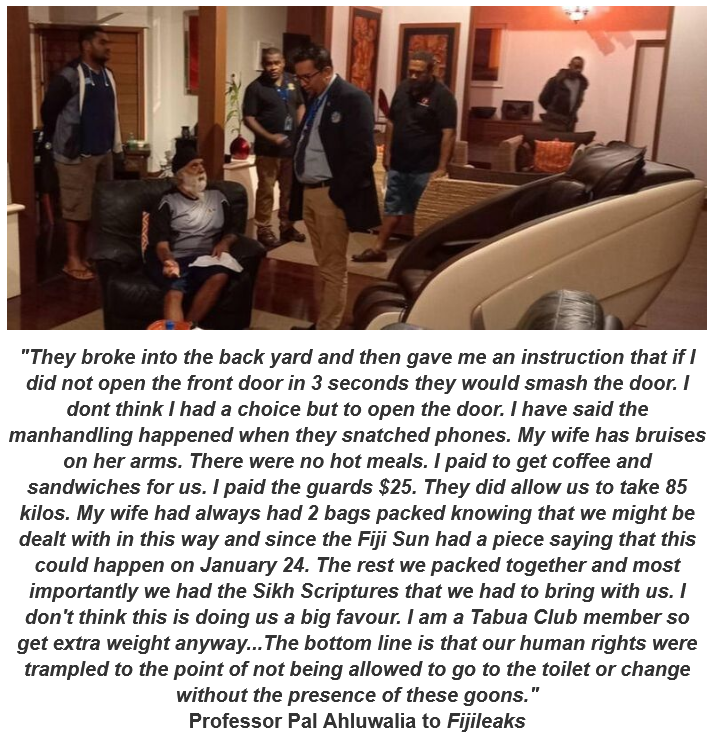

Brij Lal In early February 2021, the Fijian Government summarily revoked USP vice-chancellor Prof Pal Ahluwalia’s work permit and deported him and his wife Sandra Price for allegedly breaching some as yet unspecified breaches of the Fiji Immigration Act.

Fiji’s heavy-handed unilateral decision caused consternation among the twelve member countries of the Pacific region who collectively ‘own’ the regional university, claiming correctly that the business of hiring and firing the head of the regional organisation was the prerogative of the University Council, not of any one member of it.

To the extent that Fiji thought its unilateral action was justified, it was clearly wrong. In early June, the USP Council finally delivered justice to Pal Ahluwalia by giving him a new three-year contract with an option for another two.

It further agreed to have the VC relocate to the university’s Samoa Campus, already the home of its Agriculture School. Fiji’s loss is Samoa’s huge gain.

Fiji cavilled at the legality of the USP Council’s decision, without understanding that the contract was given pursuant to the provisions of the USP Charter. Political points were being manufactured out of nothing.

But if illegality was the issue, as the Fijian Attorney-General claimed, then why not have the matter tested in a court of law, preferably outside Fiji, and be done with it rather than making a political football of it and in the proses impugning the character and competence of the University Council to its own detriment.

Similarly, if some appointments or promotions at the university were deemed questionable, why not have them transparently investigated, too?

Fiji will unfortunately not let USP alone. Its over-extended but indefatigable A-G, a prime mover behind the scenes, will keep the USP pot boiling for some time under one pretext or another.

The turbulence at the university came at a particularly inopportune moment in regional affairs when the strength and integrity of regional organisations were under threat.

There was Fiji’s temper tantrums regarding Australia’s and New Zealand’s membership of the Pacific Islands Forum and its sponsorship of a rival Pacific Islands Development Forum which went no where.

Then, most recently, was the decision of the Federated States of Micronesia to walk away from the Forum when its turn to nominate the Forum’s Secretary General was disregarded.

And there are ongoing internal political crises in individual island countries which have potentially negative implications for regional affairs.

One hopes that the virus of dissension and instability will not extend to other regional institutions such as the Forum Fisheries Agency, South Pacific Regional Environment Program, the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, among others.

One thing the region needs above all else at the moment is solidarity to meet the challenges facing small island nations: the challenges of climate change, global health crises, environmental degradation, poverty, among many others. Solidarity rather than fragmentation is the crying need of the day for small island states.

The USP saga has brought un-sought spotlight on Fiji. It seems as clear as broad daylight to me that Fiji’s decision to deport Prof Ahluwalia and his partner, was not because he had breached some unspecified sections of the Fijian Immigration Act but because he exposed apparent breaches of good governance practices by the higher echelons of the USP administration implicating, Fiji citizens close to the FijiFirst Government of Voreqe Bainimarama.

I believe that this in the end is what triggered Fiji’s brutal reaction. Fiji’s reaction was sadly predictable. Deporting or otherwise harassing real and imagined opponents has become the modus operandi of the Fijian administration.

Fiji though is the biggest loser in the USP saga. Its reputation for fairness and probity in regional affairs is at its lowest ebb ever.

In truth, it has been on the wane since the Bainimarama coup of 2006 which overthrew a democratically elected government headed by an indigenous Fijian, Laisenia Qarase. The sense in the region, as I have been told on many occasions, is that Fiji is wilfully insensitive to the needs and concerns of its smaller neighbours and will try to use any means to have its way among them.

Fiji once enjoyed the unqualified esteem of its neighbours through consensus. Now it is seeking to assert its dominance through bullish behaviour. It will be a long time before Fiji again regains a semblance of its former place.

There are other casualties as well. The reputation of Australia and New Zealand has also suffered greatly. Both these countries are key players in the region and important benefactors of the regional university and other institutions. Both showed a strange, unaccustomed lack of courage and leadership in the USP saga. They saw the tussle between Prof Ahluwalia and the key senior players of the USP administration as a problem between individuals rather than as a manifestation of a deeper structural problem, which is Fiji’s determination to have a lion’s share of say in the management and running of the university.

Instead of demanding transparent accountability from those implicated in Prof Ahluwalia’s investigation, they bent over backwards to accommodate Fiji or, at best, to look the other way.

Australia particularly is currying favour with Fiji for larger strategic reasons of its own and is therefore reluctant to be forthright in its responsibilities. China’s presence in the South Pacific region looms large in Australia’s thinking.

It mistakenly thinks that by supporting Fiji, they might be able to restrain Fiji’s current China enthusiasm. Fiji, for its part, is acutely aware of the power of the China card it has in its hands and will play it to its maximum advantage irrespective of its broader regional implications.

The way Australia and New Zealand have behaved during the USP saga has not been unnoticed in the region. It has damaged their own reputation in places where they sought to assert their influence.

In a recent meeting of the USP Council, a representative from Fiji broke rank and made the pertinent point about not overlooking at the human dimension of the story rather than simply talking about individuals in the abstract.

He had Prof Ahluwalia in mind and what he had been put through. Ironically, the very person FijiFirst government sought to demonise, has emerged as the biggest winner of them all.

On surface, Prof Ahluwalia’s vindication and re-appointment may seem a bit of a mystery, but there are in fact many reasons for it. In the first place is the man himself. What kind of person is Pal Ahluwalia?

The Kenyan-born Canadian academic with extensive research, teaching and administrative experience in Canada, the US and the UK and Australia, is no ordinary garden variety academic.

He is an unassuming, fundamentally decent human being. He is a respected scholar of African politics and a Fellow of the Australian Social Sciences Academy no less.

He understands and practises the values and principles which underpin academic life. This is transparent and palpable. He is a multi-talented person: a sometime disciple, shagird, of renowned Pakistani tabla maestro Ustad Tari Khan. He is at home in several languages.

He is multicultural in his outlook and values to the core. And he is a person of deep spirituality, a devout Sikh, a lifelong vegetarian and teetotaller for whom praying is an integral part of his daily routine.

This perhaps more than anything, explains his incredible rapport with his students and staff, many of who themselves come from deep faith-based cultures. He often prayed with them publicly.

He and Sandra Price regularly opened their vice chancellor’s house for shared meals and casual fellowship with members of the university community in a way that had never happened before.

A Kenyan born Indian person with quintessential Pacific sensibilities! In modern lingo, he was a true ‘Pacifican’. It became clear to everyone that this elderly couple was an integral part of the university community, not apart or above it. The vice chancellor never stood on protocol or rank. The contrast with his predecessor was stark. The two were chalk and cheese in their persona.

Slightly more perplexing at first glance is Prof Ahluwalia’s striking rapport with regional leaders who have been among his staunchest supporters.

Part of this may have to do with their disenchantment with the former USP regime and Fiji’s capricious behaviour and the un-Pacific way he was treated by them. But there is no doubt that there is genuine regard for a person who is principled and completely at home in regional settings.

In this regard, he resembles Dr James Maraj of Trinidad, one of USP’s former vice chancellors. The sight of a rolly-polly Pal in the company of rolly-polly Pacific leaders is endearing.

USP holds a special place in the hearts and minds of those of us who studied there during their salad days. It was for us a place of learning which opened windows on the unexplored and even unknown world beyond the horizon, and set us on a path of adventure and exploration that took us to the pinnacle of our professions.

It was also a place of youthful romance for many of us, a place where we formed cross-cultural friendships across the region which have lasted a lifetime. For our networking and influence in the region, we were sometimes affectionately dubbed the “USP Mafia”. We, for our part, wore that as a badge of honour.

Fiji retains a special place in my heart as well even though we, my wife and I, have been banned for life from returning to the country of our birth. I genuinely want Fiji to do well, to have its proper place at the table.

But I also accept as a matter of reality that Fiji stands diminished in a region where it once held sway.

The current course it has set for itself is counterproductive to its own long-term interests in the region of which it is inextricably a part both by the logic of its history and the realities of its geography.

PROFESSOR BRIJ V LAL is a Fiji-born USP alumni and author of many books. He now resides in Brisbane. The views expressed are the author’s and do not reflect the views of this newspaper. Source: The Fiji Times, Saturday, 12 June 2021

Fiji’s heavy-handed unilateral decision caused consternation among the twelve member countries of the Pacific region who collectively ‘own’ the regional university, claiming correctly that the business of hiring and firing the head of the regional organisation was the prerogative of the University Council, not of any one member of it.

To the extent that Fiji thought its unilateral action was justified, it was clearly wrong. In early June, the USP Council finally delivered justice to Pal Ahluwalia by giving him a new three-year contract with an option for another two.

It further agreed to have the VC relocate to the university’s Samoa Campus, already the home of its Agriculture School. Fiji’s loss is Samoa’s huge gain.

Fiji cavilled at the legality of the USP Council’s decision, without understanding that the contract was given pursuant to the provisions of the USP Charter. Political points were being manufactured out of nothing.

But if illegality was the issue, as the Fijian Attorney-General claimed, then why not have the matter tested in a court of law, preferably outside Fiji, and be done with it rather than making a political football of it and in the proses impugning the character and competence of the University Council to its own detriment.

Similarly, if some appointments or promotions at the university were deemed questionable, why not have them transparently investigated, too?

Fiji will unfortunately not let USP alone. Its over-extended but indefatigable A-G, a prime mover behind the scenes, will keep the USP pot boiling for some time under one pretext or another.

The turbulence at the university came at a particularly inopportune moment in regional affairs when the strength and integrity of regional organisations were under threat.

There was Fiji’s temper tantrums regarding Australia’s and New Zealand’s membership of the Pacific Islands Forum and its sponsorship of a rival Pacific Islands Development Forum which went no where.

Then, most recently, was the decision of the Federated States of Micronesia to walk away from the Forum when its turn to nominate the Forum’s Secretary General was disregarded.

And there are ongoing internal political crises in individual island countries which have potentially negative implications for regional affairs.

One hopes that the virus of dissension and instability will not extend to other regional institutions such as the Forum Fisheries Agency, South Pacific Regional Environment Program, the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, among others.

One thing the region needs above all else at the moment is solidarity to meet the challenges facing small island nations: the challenges of climate change, global health crises, environmental degradation, poverty, among many others. Solidarity rather than fragmentation is the crying need of the day for small island states.

The USP saga has brought un-sought spotlight on Fiji. It seems as clear as broad daylight to me that Fiji’s decision to deport Prof Ahluwalia and his partner, was not because he had breached some unspecified sections of the Fijian Immigration Act but because he exposed apparent breaches of good governance practices by the higher echelons of the USP administration implicating, Fiji citizens close to the FijiFirst Government of Voreqe Bainimarama.

I believe that this in the end is what triggered Fiji’s brutal reaction. Fiji’s reaction was sadly predictable. Deporting or otherwise harassing real and imagined opponents has become the modus operandi of the Fijian administration.

Fiji though is the biggest loser in the USP saga. Its reputation for fairness and probity in regional affairs is at its lowest ebb ever.

In truth, it has been on the wane since the Bainimarama coup of 2006 which overthrew a democratically elected government headed by an indigenous Fijian, Laisenia Qarase. The sense in the region, as I have been told on many occasions, is that Fiji is wilfully insensitive to the needs and concerns of its smaller neighbours and will try to use any means to have its way among them.

Fiji once enjoyed the unqualified esteem of its neighbours through consensus. Now it is seeking to assert its dominance through bullish behaviour. It will be a long time before Fiji again regains a semblance of its former place.

There are other casualties as well. The reputation of Australia and New Zealand has also suffered greatly. Both these countries are key players in the region and important benefactors of the regional university and other institutions. Both showed a strange, unaccustomed lack of courage and leadership in the USP saga. They saw the tussle between Prof Ahluwalia and the key senior players of the USP administration as a problem between individuals rather than as a manifestation of a deeper structural problem, which is Fiji’s determination to have a lion’s share of say in the management and running of the university.

Instead of demanding transparent accountability from those implicated in Prof Ahluwalia’s investigation, they bent over backwards to accommodate Fiji or, at best, to look the other way.

Australia particularly is currying favour with Fiji for larger strategic reasons of its own and is therefore reluctant to be forthright in its responsibilities. China’s presence in the South Pacific region looms large in Australia’s thinking.

It mistakenly thinks that by supporting Fiji, they might be able to restrain Fiji’s current China enthusiasm. Fiji, for its part, is acutely aware of the power of the China card it has in its hands and will play it to its maximum advantage irrespective of its broader regional implications.

The way Australia and New Zealand have behaved during the USP saga has not been unnoticed in the region. It has damaged their own reputation in places where they sought to assert their influence.

In a recent meeting of the USP Council, a representative from Fiji broke rank and made the pertinent point about not overlooking at the human dimension of the story rather than simply talking about individuals in the abstract.

He had Prof Ahluwalia in mind and what he had been put through. Ironically, the very person FijiFirst government sought to demonise, has emerged as the biggest winner of them all.

On surface, Prof Ahluwalia’s vindication and re-appointment may seem a bit of a mystery, but there are in fact many reasons for it. In the first place is the man himself. What kind of person is Pal Ahluwalia?

The Kenyan-born Canadian academic with extensive research, teaching and administrative experience in Canada, the US and the UK and Australia, is no ordinary garden variety academic.

He is an unassuming, fundamentally decent human being. He is a respected scholar of African politics and a Fellow of the Australian Social Sciences Academy no less.

He understands and practises the values and principles which underpin academic life. This is transparent and palpable. He is a multi-talented person: a sometime disciple, shagird, of renowned Pakistani tabla maestro Ustad Tari Khan. He is at home in several languages.

He is multicultural in his outlook and values to the core. And he is a person of deep spirituality, a devout Sikh, a lifelong vegetarian and teetotaller for whom praying is an integral part of his daily routine.

This perhaps more than anything, explains his incredible rapport with his students and staff, many of who themselves come from deep faith-based cultures. He often prayed with them publicly.

He and Sandra Price regularly opened their vice chancellor’s house for shared meals and casual fellowship with members of the university community in a way that had never happened before.

A Kenyan born Indian person with quintessential Pacific sensibilities! In modern lingo, he was a true ‘Pacifican’. It became clear to everyone that this elderly couple was an integral part of the university community, not apart or above it. The vice chancellor never stood on protocol or rank. The contrast with his predecessor was stark. The two were chalk and cheese in their persona.

Slightly more perplexing at first glance is Prof Ahluwalia’s striking rapport with regional leaders who have been among his staunchest supporters.

Part of this may have to do with their disenchantment with the former USP regime and Fiji’s capricious behaviour and the un-Pacific way he was treated by them. But there is no doubt that there is genuine regard for a person who is principled and completely at home in regional settings.

In this regard, he resembles Dr James Maraj of Trinidad, one of USP’s former vice chancellors. The sight of a rolly-polly Pal in the company of rolly-polly Pacific leaders is endearing.

USP holds a special place in the hearts and minds of those of us who studied there during their salad days. It was for us a place of learning which opened windows on the unexplored and even unknown world beyond the horizon, and set us on a path of adventure and exploration that took us to the pinnacle of our professions.

It was also a place of youthful romance for many of us, a place where we formed cross-cultural friendships across the region which have lasted a lifetime. For our networking and influence in the region, we were sometimes affectionately dubbed the “USP Mafia”. We, for our part, wore that as a badge of honour.

Fiji retains a special place in my heart as well even though we, my wife and I, have been banned for life from returning to the country of our birth. I genuinely want Fiji to do well, to have its proper place at the table.

But I also accept as a matter of reality that Fiji stands diminished in a region where it once held sway.

The current course it has set for itself is counterproductive to its own long-term interests in the region of which it is inextricably a part both by the logic of its history and the realities of its geography.

PROFESSOR BRIJ V LAL is a Fiji-born USP alumni and author of many books. He now resides in Brisbane. The views expressed are the author’s and do not reflect the views of this newspaper. Source: The Fiji Times, Saturday, 12 June 2021