Fijileaks Founding Editor-in-Chief: | Private Collections |

By early February 1937 he was confronted with a major ‘Indian problem’ which was visible on the horizon:

‘What are 200,000 people in a country which could easily support ten times that number? However at their present increase the future lies with the Indians. The Fijian is so far behind.’

He also remembered one grey-haired old Indian coming to him and saying: ‘Where will you find in Fiji the Indian sitting under the tree his father planted.’ He had an Indian cook, Bala.

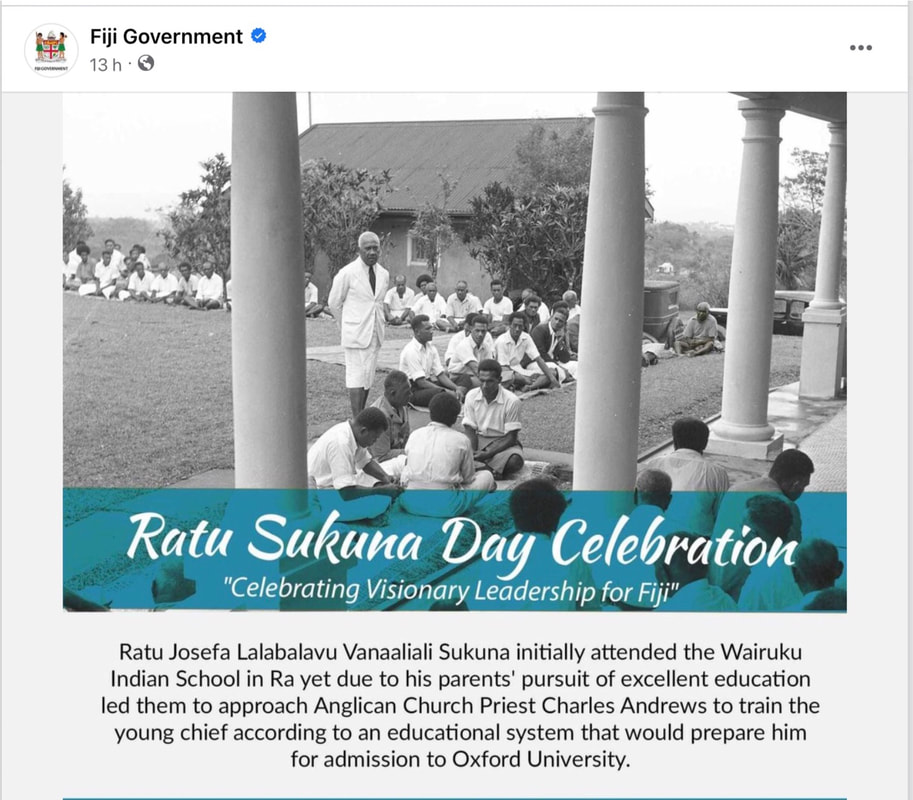

On 26 February 1937, in a letter to Gerald Creasy of the British Colonial Office in London, he refers for the first time to Ratu Sukuna. At the time when Richards arrived in Suva, Ratu Sukuna was on a trip to Europe paid for by ‘voluntary’ contributions from the people. Richards proposed to ask him if this were true when he returned, but he had no intention of breaking him.

‘He is too potentially valuable and he would be a very dangerous malcontent. He is 49 years of age, a member of Leg Co and votes as he pleases. I have a mind to make him my Adviser on Native Affairs. I propose to gamble a little on him, to trust him and, I hope, to use him for the good of the country in solving the land question.’

His choice was a good one. They became friends with complete trust in each other and together they worked on Richards’ plan for land reform which would radically change the old communal system. The basis of the plan rested on the fact that the Fijian community possessed five times as much land as they could use either then or at any time in the future having regard to their visible population trends, and in pointing this out in speeches which he made to Fijian assemblies in every province throughout the country.

Richards made it plain that, if they insisted on holding back and they could not hope to use, which was their prerogative, the future of their country must be troubled. With diplomatic impartiality, he went on to point out what the Indians had done to bring prosperity to their country.

He wrote to Creasy on 7 September 1937: ‘People tell me that I have the confidence of the Fijians and anyway the name of the King’s representative is still something to conjure with here. The Fijians trust the King and will take from the Governor what they would take from no one else. Perhaps with Sukuna’s help I may be able to solve the problem. My idea is to turn him on to dividing up the country into lands surrendered by them to the Crown to be held in trust and allocated at the Crown’s will on what terms it considers just to anyone, Fijian or Indian or European, but the chief objective is the Indian. No more freehold - only long leases. I should constitute a small Board of which the Governor would be Chairman and would always sit as such, to deal with difficult decisions during the land division, and afterwards to be in general control of the allocations.’

All rent revenue from the land so allocated was to be paid into a welfare fund for the benefit of the indigenous Fijian population.

Ratu Sukuna supported the plan whole-heartedly and Richards warmly acknowledged the lead which he took in persuading the chiefs to agree to it. There were already young Fijians who were impatient with the old communal system and wanted personal freedom from it, but nevertheless the readiness of the chiefs and their people to agree to the proposals was probably the finest act of trust in colonial history.

Ratu Sukuna estimated that he could draw up the most equitable division of land within two or three years.

Unfortunately, Richards was transferred to Jamaica a few months later, and although the scheme was proceeded with for a time, it was hindered by the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 before it could be implemented.

‘What are 200,000 people in a country which could easily support ten times that number? However at their present increase the future lies with the Indians. The Fijian is so far behind.’

He also remembered one grey-haired old Indian coming to him and saying: ‘Where will you find in Fiji the Indian sitting under the tree his father planted.’ He had an Indian cook, Bala.

On 26 February 1937, in a letter to Gerald Creasy of the British Colonial Office in London, he refers for the first time to Ratu Sukuna. At the time when Richards arrived in Suva, Ratu Sukuna was on a trip to Europe paid for by ‘voluntary’ contributions from the people. Richards proposed to ask him if this were true when he returned, but he had no intention of breaking him.

‘He is too potentially valuable and he would be a very dangerous malcontent. He is 49 years of age, a member of Leg Co and votes as he pleases. I have a mind to make him my Adviser on Native Affairs. I propose to gamble a little on him, to trust him and, I hope, to use him for the good of the country in solving the land question.’

His choice was a good one. They became friends with complete trust in each other and together they worked on Richards’ plan for land reform which would radically change the old communal system. The basis of the plan rested on the fact that the Fijian community possessed five times as much land as they could use either then or at any time in the future having regard to their visible population trends, and in pointing this out in speeches which he made to Fijian assemblies in every province throughout the country.

Richards made it plain that, if they insisted on holding back and they could not hope to use, which was their prerogative, the future of their country must be troubled. With diplomatic impartiality, he went on to point out what the Indians had done to bring prosperity to their country.

He wrote to Creasy on 7 September 1937: ‘People tell me that I have the confidence of the Fijians and anyway the name of the King’s representative is still something to conjure with here. The Fijians trust the King and will take from the Governor what they would take from no one else. Perhaps with Sukuna’s help I may be able to solve the problem. My idea is to turn him on to dividing up the country into lands surrendered by them to the Crown to be held in trust and allocated at the Crown’s will on what terms it considers just to anyone, Fijian or Indian or European, but the chief objective is the Indian. No more freehold - only long leases. I should constitute a small Board of which the Governor would be Chairman and would always sit as such, to deal with difficult decisions during the land division, and afterwards to be in general control of the allocations.’

All rent revenue from the land so allocated was to be paid into a welfare fund for the benefit of the indigenous Fijian population.

Ratu Sukuna supported the plan whole-heartedly and Richards warmly acknowledged the lead which he took in persuading the chiefs to agree to it. There were already young Fijians who were impatient with the old communal system and wanted personal freedom from it, but nevertheless the readiness of the chiefs and their people to agree to the proposals was probably the finest act of trust in colonial history.

Ratu Sukuna estimated that he could draw up the most equitable division of land within two or three years.

Unfortunately, Richards was transferred to Jamaica a few months later, and although the scheme was proceeded with for a time, it was hindered by the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 before it could be implemented.