Fijileaks: We have decided not to reproduce Part Four, Peoples Coalition: Its Time for Political Divorce! A Tale of ‘Political Bulumakau Sele or Badhia Bail’ in a ‘Constitutional China Shop’. Excerpts: We had likened the inability of the Fiji Labour Party to act decisively over the rift between the Fijian Association Party (FAP) and the Party of National Unity (PANU), who made up Chaudhry’s People's Coalition Government, to that of ‘a castrated political bull’ in a ‘constitutional China shop’. We had blamed the provisions of the 1997 Constitution of Fiji, with its provisions for mandatory power sharing, and the new electoral system, as the overreaching reasons for Chaudhry Government’s downfall, where the religious amorals met the political amorals from different political parties and races in a grand conspiracy to make Fiji, ‘The Way The World Shouldn’t Be’. We now call upon the Fiji Labour Party to dissolve the People's Coalition and return to the negotiating constitutional table to iron out some of the defects in the 1997 Constitution of Fiji. Fiji’s future lies in the proliferation of multi-racial political parties and not in enforced marriages of convenience with racially-based and overtly pseudo nationalistic Fijian and Indo-Fijian parties. When the new 1997 Constitution of Fiji was unanimously passed by both Houses of Fiji’s Parliament, a jubilant Chaudhry declared after the parliamentary vote that a long-standing grievance about the 1990 Constitution had ended. ‘I think if all of us decide to work together, remove all forms of discrimination, work as a united nation, we have a future ahead of us’, he said. Multi-racialism is our only lighthouse to a brighter and harmonious Fiji.

Conclusion: Confronting Fijian realities and futures: A Mirror for Reflection

By VICTOR LAL, Fiji's Daily Post, 2000

"The Deed of Cession has been regarded as the charter of Fijians indigenous rights. It has been appropriated by Fijians of different political persuasions for different purposes. It is worth remembering that it was mostly the eastern chiefs who had made an unconditional cession of their islands to Great Britain. As Governor Sir Ronald Garvey noted in his Cession Day’s speech in 1957, ‘to read into the Deed more than that, to suggest, for instance, that the rights and interests of the Fijians should predominate over everything else, does not service either to the Fijian people or to their country’. The adoption of that view, Sir Ronald continued, ‘would mean complete protection and no-self-respecting individual race wants that because, ultimately, it means that those subject to it will end up as museum pieces’. VICTOR LAL

‘There was nothing in the Deed of Cession to say that when England was to hand over Fiji that it was to hand it over holus-bolus to the Fijian people and to the Fijian people alone. There was nothing whatsoever written in it and as the Fijian chiefs gave Fiji unreservedly to Great Britain, my interpretation is that if Great Britain wants to give it back she gives it back in the condition which she finds it. It does not necessarily mean that she should give it back to the Fijian people.’

Ratu William Toganivalu, a high chief and Cabinet Minister in Alliance Government, Fiji's House of Representatives in June 1970

When a segment of the elite Fijian military forces mutinied against their own commander, Commodore Frank Banimarama, ending in bloody death and destruction, it shook the Fijian race to its very core. Banimarama escaped the assassination attempt on his life, but the tragic uprising was a salutary reminder to the Fijians that ‘The Enemy Was Within’, and not as some have, and continue to religiously suggest, inside the Indo-Fijian community, led by the bogeyman, the deposed Prime Minister Mahendra Pal Chaudhry.

The attempted assassination of Banimarama, if it had succeeded, would have imposed on the nation another genetically modified version of Fijian leadership, and supported by a new military dictator, in the name of indigenous rights. The successful perpetrators of the coup would have claimed that the current crop of Fijians in the Interim Administration were not ruthlessly nationalistic enough in upholding Fijian rights, especially land rights. But the attempted coup failed for the second time in the new millennium because a segment of the troops loyal to Banimarama stood firmly behind their military leader. It also injected a new lease of life in the continuance of the Interim Government, and spared those running the country from suffering the same fate as the Chaudhry government. Many members of the Interim Regime, no doubt, if the attempted coup had succeeded, would have been given a bitter taste of what it was like for Chaudhry and others to be deprived of their liberty for 56 days at the hands of another pseudo saviour of the Fijian race. They would have become a new set of hostages at the hands of another George Speight, a man not in impeccably shinning wolves clothing but a military strongman in full military regalia with shinning medals proudly plastered to his chest, and repeating the words of the Father of the Coups, Sitiveni Rabuka: ‘NoOther Way.’

What is most surprising however is that, unlike the dismissal of the Chaudhry government, Bainimarama was not removed from his post, nor were the members of the Interim government, on the grounds that ‘we must accept the reality of the Fijiansituation, and accept the demands of the hardliners for the supremacy of Fijians in their own and only country’. The whole bloody and violent affair is being quietly brushed under the mat because it is in conflict with the avowed aims and objectives of some Fijians to re-introduce apartheid in Fiji. It is equally baffling to ask: why did these soldiers mutiny when they already had a Fijian leading a predominantly Fijian Interim Government, charged to draw up a new Constitution to ensure Fijian supremacy under the South Pacific sun. If Chaudhry had to be bundled out of office because he was not an authentic taukei, what was wrong with Commodre Frank Bainimarama, a high-ranking Fijian chief in his own right. The partial answer may be found in the public outburst of Bainimarama himself before the assassination attempt, that the Fijian chiefs were only united in their hatred of the Indo-Fijians. His comments, like the attempted mutiny, sent a chill down the spines of the commoner Fijians, chiefs, and those leading the Great Council of Chiefs. Coups and counter-kuttus in Fiji

What were the underlying causes of the attempted mutiny will remain a matter of conjecture and speculation for years to come. Who were the key players behind the scene will never be known. We have been however reliably informed that Sitiveni Rabuka and the Police Commissioner Isikia Savua were part of the grand conspiracy to bring down the Chaudhry government.But what we are sure of and can say with certainty is that a group of Fijians had plotted against another group of Fijians in the historical power struggle for the control of the nation. In other words, coups and counter-coups have been a regular feature of the Fijian way of life for settling disputes. One long-standing Fijian friend of mind recently tried to make a joking humour of what he acknowledged was a serious and disastrous problem for the Fijians. He wrote: ‘Whether it is Sitiveni Rabuka’s Coup 1 and Coup 11, or George Speight’s Attempted Coup 1 and the rebel soldiers Attempted Coup 11, it is inevitable that whenever a coup takes place, you can be sure that the political kuttu (head lies or neats) is ready to counter-attack our heads. In other words, one political kuttumerely takes over from another politicalkuttuthe control ofour heads, and we end up dying from lack of blood for providing our head as a fertile ground for the political kuttu to thrive politically. The kuttumoves on to his next victim. This is also true of our Indo-Fijian brethren and sisters who have to enduredifferent types of political kuttus in their own community.’On a more serious note, coups and counter-coups are not new in Fiji; it existed even before the arrival of the Indo-Fijians as indentured labourers.

Its genesis can be traced as far back to the so-called ‘Bau Constitution’ of the 19th Century which vainly tried to impose constitutional solutions to Fiji’s intricate racial, tribal, and provincial problems.

Coups, counter coups and ‘Bau Constitution’ - The Cakobau Government

According to the records of the colonial government’s archivist, A.I. Diamond, the advent of Europeans resulted in a marked increase in the extent and ferocity of native warfare. Towards 1850, power and influence in the Fiji were beginning to centre on the chiefdoms of Bau, Rewa, Somosomo, Verata, Naitasiri, Macuata, Bua and Lakeba. Of these Bau was undoubtedly the most powerful, her chiefs having extended their influence by means of warfare, intrigue, and judicious alliances over nearly one-third of Fiji. By 1850, Cakobau had achieved a position so near to paramountcy that foreigners had begun to address him as Tui Viti (King of Fiji). Cakobau’s claim to the title was not generally recognised by Fijians outside his own dominions, and it would scarcely merit mention here were it not for the fact that it brought him later into conflict with the United States government. In 1855, the latter had brought indemnity claims against him for damage and loss of property said to have been sustained by Americans at the hands of the Fijians.

Although Cakobau himself was not personally responsible with the incidents on which the claims were based, the US government insisted that as King of Fiji, he was responsible for the actions of his subjects. The claims amounted in the end to over $45,000 (dollars), a sum which Cakobau could not hope to raise by himself, and as they were pressed with the threat of warlike reprisals the Vunivalu found himself in circumstances which could lead to his downfall.To add to his difficulties, Cakobau began to find his supremacy threatened after 1855 by the rise to power of Ma’afu. The latter, a Tongan war chief, had come to Fiji with his retainers in 1848, thirty-one years before the introduction of Indian indentured labourers to Fiji. After aiding Cakobau in a campaign against the chiefs of Rewa and their allies, Ma’afu had established himself in Lau. From there he began to extend his influence into other parts of the Group until by 1865 he controlled Beqa and large parts of the western coasts of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. Cakobau watched his rival’s activities with increasing alarm, seeing in them preparations for his own eventual subversion and overthrow. Harassed by these difficulties, Cakobau turned for advice to the British Consul, William Thomas Pritchard, who responded by urging him to offer Fiji to Great Britain. Though Cakobau had no authority to make such an offer, he in his extremity, agreed and a formal Deed of Cession was drawn up on 12 October 1858, offering Fiji to the British government on certain conditions, including the payment of the American claims in return for a conveyance of 200,000 acres of land to the British crown.

The offer was subsequently acknowledged, ratified and renewed by the Fijian chiefs on 14 December 1859. The Deed of Cession was taken to England for presentation by Pritchard himself who made vigorous efforts on arrival to ensure that the offer was favourably received. After some delay, the British government despatched a Colonel W.G. Smythe to Fiji to investigate and report on the expediency of annexation. Smythe’s report, however, was unfavourable, and in 1862 the Government of New South Wales in Australia was instructed by the British authorities to inform Cakobau and his supporters that the offer of cessionhad been declined. Shortly after this refusal Cakobau repeated the offer to the United States government. The latter, however, being engaged at the time in Civil War, sent no reply.Between 1865 and 1871 several attempts were made to introduce a measure of political stability into Fiji by means of Confederations, but for various reasons, more especially the inexperience and mutual suspicion and hostility of the leading chiefs, none of the Confederacies succeeded. In 1865 Cakobau and Ma’afu were persuaded to co-operate in the establishment of a Confederacy of the six most powerful native dominions in Fiji; these being Bau, Rewa, Lakeba, Bua, Cakaudrove, and Macuata.

The chieftains of the six, claiming to speak for the whole of Fiji, constituted themselves a General Assembly with power to legislate for a code of laws which was to be effective throughout Fiji. The members states were to retain their sovereignty, but each agreed to observe the common code of laws and to unite for the preservation of peace and order. The Confederation was inaugurated on 8 May 1865 under the Presidency of Cakobau. Much hope was entertained for the success of the venture and for the first two years it functioned well enough. But in 1867, when Ma’afu began to canvas support for himself as President of the Assembly, Cakobau and several of the leading Fijian chiefs withdrew and the Confederacy collapsed. Upon the failure of the 1865 Confederation, Ma’afu and Cakobau immediately set up institutions for the control of their own spheres of influence. Ma’afu, with the help of his European secretary, R. S. Swanston, induced the chiefs of Lau, Cakaudrove and Bua to combine under his leadership in a Confederation (the Tovata i Viti or Tovata i Lau), similar in character to the Confederation of1865. At the same time, Cakobau, urged on by the European settlers at Levuka, adopted for his own dominion the form of a European monarchy modelled on the Hawaiian Constitution.

The latter is of particular interest as it afterwards formed the basis of theso-called Cakobau Government of 1871. The Lau Confederation, under Ma’afu’s direction was moderately successful and held together until 1871. Ma’afu later assuming the title of Tui Lau. The Bau monarchy, however, collapsed within a year mainly as a result of internal dissension and lack of revenues. In 1869, an attempt was made to re-instate it under a revised constitution but it failed almost immediately and for the same reasons as its predecessor.The huge influx of White settlers during the cotton boomof the 1860s brought with it a corresponding increase in the need for stable and unified government. Hitherto the British, American and German consuls, supported by occasional visits from warships, had managed fairly effectively to protect and regulate the affairs of the European population and to mediate between their own nationals and the Fijians.

The competency of the Consuls, however, was limited and by 1870 it was clear that if the lives and property of the settlers and the interests of the natives themselves were to be secured a local government would have to be established with legislative authority over the whole of Fiji and coercive power sufficient to keep the peace and enforce the law.Fiji’s first coup Although most of the settlers were agreed in principle on the need for such a government, constant dispute between the various sections of the European population made concerted action difficult. In the end, the ‘national’ government was established by means of a coup. In the early months of 1871,a group of Levuka businessmen formed a conspiracy and approached Cakobau in secret with a proposal that he place himself at the head of a Government claiming sovereignty over the whole of Fiji. The attempt could easily have ended, like others before it, in a fiasco. This one, however, came as a complete surprise and was, moreover, well-timed. Cakobau was occupied in the successful conclusion of a campaign against the Lovoni people on the island of Ovalau. Thus not only was his prestige enhanced but that victory was turned to account by the penalty meted out to the Lovoni people.

The latter were expropriated and sold into servitude to white planters at the rate of £3 a head and a yearly hire of the same amount. The revenue from the 'hire’ of Lovoni labour was considerable and as it was placed at the disposal of the new Government the latter began, unlike its predecessors, with at least one assured source of annual income.The proclamation of the ‘Cakobau Government’, as it has come to be known, at first raised a storm of protest among the Europeans in Levuka. But opposition was greatly reduced by the publication of a ‘Gazette’ containing among other things, an undertaking by the Executive to delay the initiation of all matters other than those of urgent public necessity until a House of Representatives had been assembled. With this assurance, the majority of the settlers were content for the time being to accept the new Government as a ‘fait accompli’ and many even lent their active support to it.It was obvious to most, however, that the future of the Government depended heavily upon the reaction of Ma’afu. Ma’afu was not only the leader of a powerful alliance of chiefs, but could easily, if he chose, set himself up as the champion of the dissident elements among the Europeans.

But surprisingly enough Ma’afu offered no resistance to the coup and even agreed to co-operate with the new Government. On 22 July he visited Levuka and, in the course of discussions with Cakobau lasting two days, acknowledged him as TuiViti, took the oath of allegiance and abandoned all territorial claims outside Lau, the seat of his power. In return he was made Viceroy of Lau with salary of £800 and was given a clear title to the islands of Moala, Matuku and Totoya. The acquiescence ofMa’afu effectively disposed of the threat of serious resistance from the native Fijians and by the end of the year all the ruling chiefs had tendered their allegiance to Cakobau.The ‘Bau Constitution’The first Gazette, issued by the new Government on 5 June 1871, gave notice that Cakobau, Tui Viti, had been pleased under the Bau Constitution to appoint an Executive (mostly Europeans) consisting of the following: Sydney Charles Burt, George Austin Woods, John Temple Sagar, James Cobham Smith, Gustavas Hennings, and Ratu Savenaca and Ratu Timoci. Government Gazette No.2, published on 10 June 1871, contained explanations of the main causes which had led to the appointment of the Executive.

These were three: (a) the largely increasing European population, (b)the growing want of confidence in commercial matters, and (c) the hesitation of merchants and financial interests in the colonies to deal with investments in Fiji until a form of government should be adopted. The Gazette also gave notice that delegates from all the districts in Fiji had been summoned to meet at Levuka on 1 August to discuss and amend the Constitution of 1867. The House of Delegates met under the chairmanship of J.S. Butters, the former mayor of Melbourne and Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Victoria, and after two weeks deliberation, passed the Constitution Act of Fiji, 1871. This Act was signed by Cakobau on 18 August and came into force on the 1 October. The first Parliament of the Cakobau Government was opened by Cakobau on 3 November 1871. It sat until the 17 December, having passed about 20 ‘Bills’.

The Second Coup Attempt

By March 1872 there was evidence of growing distrust of, and lack of confidence in, the Government. Much jealousy was displayed over ministerial and public service appointments, and there was widespread complaint at what was described as ‘the absurd attitudes and arrogant bearing’ adopted by certain Ministers towards the public. The task of the Cakobau Government was further hampered by the effects of an economic recession resulting from the collapse of the market for ‘sea-island’ cotton. Many of the white settlers suddenly found themselves in acute financial distress and resistance to taxation increased. Revolutionary movements became active and on one occasionan armed insurrection inspired by an organisation calling itself the ‘Ku-Klux-Klan’ very nearly succeeded in overthrowing the Government. The fact that the Government survived this threat largely as a result of assistance offered by a British man-of-war did little to enhance its stature in the eyes of the public. Resistance to the Government at length resolved itself into a demand for the dissolution of the Assembly, the holding of a new election, and the dismissal of the Premier, S.C. Burt. On 18 March the Cakobau government yielded and Burt resigned. Cakobau invited J.B.Thurston, a white Tavenui planter and one of the members of the Legislative Assembly for Tavenui district, to join the Government and the latter, upon accepting the invitation, acted as Premier in the absence of G.A. Woods, who was originally chosen for the post but who was away in Australia at the time.

The third and last session of the Legislative Assembly sat between 31 May and 12 June 1873. The principal business set down was the amendment of the Constitution Act of 1871, the operation of which had been found too expensive and cumbersome. Of the 28 members of the Assembly, only 14 attended, and of these only 5 were minority, the Government were defeated and the Cabinet accordingly resigned. Cakobau, however, declined to accept, and instead issued a Proclamation dissolving the Assembly. The Assembly never sat again and thereafter administration continued under Ministerial direction until the establishment of an Interim Government on 23 March 1874.

A general election was due to be held in 1873; but at a meeting of the King-in-Council held on 29 July 1873, at Nasova, Levuka, it was resolved that the arrangements for the election should be abolished. On 11 July 1873 Cakobau appointed a RoyalCommission to revise, consolidate and amend the laws. The Commission drew up the so-called ‘National Constitution and Fundamental Laws of the Kingdom of Fiji, 1873’, and though it received the assent of Cakobau it was never adopted, owing largely to the opposition of Commodore Goodenough and the British Consul, E.L. Layard. Throughout 1872 and 1873 resistance to the Cakobau Government, particularly on the part of the Europeans, increased. In Ba, the settlers staged a revolt and again the Government found itself obliged to accept the intervention of a British warship. By the middle of 1873 the administration was facing bankruptcy and it was clear even to its supporters that the regime could not last. Responsible elements among the European community began topress for cession of Fiji to Great Britain or the United States.

The Cession of Fiji to Great Britain

On 17 March 1874, the British Consul gave warning in a public notice that the Cakobau Government was bankrupt and cautioned all British subjects againstallowing the Government further credit. The notice further declared that British subjects accepting or retaining official posts in the Armed Constabulary were liable to prosecution under the UK Foreign Enlistment Act. The Consul’s action practically put an end to the attempt at self-government, and the newly formed Ministry strongly advised Cakobau to reconsider the question of annexation by Great Britain. A meeting of the leading Fijian chiefs was held in March, and the 21stof that month a formal offer of cession was made to the Commissioners who communicated it to the Imperial government in London.

At the meeting, held at Levuka on 23 March 1874, attended by the Commissioners, Cakobau and other high chiefs, the foreign Consuls, the Chief Secretary Thurston and the Chief Justice (St Julian), it was resolved that an Interim Government should be established to carry on the administration of Fiji pending a decision by the Imperial government on the subject of annexation.The offer of cession made on 21 March,contained terms which proved unacceptable to the British government and as a result, Sir Hercules Robinson, then Governor of New South Wales, was despatched to Fiji in September 1874, to negotiate. On 30 September Robinson telegraphed Lord Carnarvon in London: ‘The King (Thakombau) has this day signed an unconditional cession of the country. I am leaving today on a tour to obtain the signature of Ma’afu and other ruling Chiefs’. His mission was successful and on 10 October Cakobau, Ma’afu and other principal chiefs ceded the sovereignty of Fiji to Great Britain. Upon the conclusion of the Deed of Cession, Sir Hercules Robinson established a Provisional Government to carry on administration until the arrival of the Governor and the Proclamation of the Colony.

The administration of the Provisional Government terminated on the 1 September 1875, with the proclamation of the Royal Charter erecting Fiji into a separate Colony and with the assumption of office of the first resident Governor, Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon, the man responsible for introducing Indian indentured labourers into Fiji in 1879. Gordon was safeguarding the Fijian population as they were still struggling to fight off an epidemic of measles in 1875 which had killed about 40,000 of the estimated population of 150,000 Fijians. The epidemic occurred after Cakobau and his two sons, who had contracted mild cases of measles during their return voyage from a visit to Sydney, were allowed to land in Fiji before they had completely recovered. Responsibility for the disaster rested with the captain and medical officer of H.M.S Dido. They failed to impress upon E.L. Layard, the British consul for Fiji and Tonga, the serious consequences that might result from failure to place the patients in quarantine.

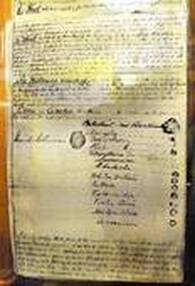

The Deed of Cession

King Cakobau had sent Queen Victoria a basket of earth to symbolise the handing over of the land of Fiji and his oldest and favourite war club. This latter item was later returned to Fiji by King George V where, topped with a silver crown and a dove of peace, it became the mace of the Legislative Council and subsequent Parliaments of Fiji. The Deed of Cession has been regarded as the charter of Fijians indigenous rights. It has been appropriated by Fijians of different political persuasions for different purposes. It is worth remembering that it was mostly the eastern chiefs who had made an unconditional cession of their islands to Great Britain. As Governor Sir Ronald Garvey noted in his Cession Day’s speech in 1957, ‘to read into the Deed more than that, to suggest, for instance, that the rights and interests of the Fijians should predominate over everything else, does not service either to the Fijian people or to their country’.

The adoption of that view, Sir Ronald continued, ‘would mean complete protection and no-self-respecting individual race wants that because, ultimately, it means that those subject to it will end up as museum pieces’. The late Ratu William Toganivalu, a high chief and Cabinet Minister in the Alliance Government, had argued in the House of Representatives in June 1970: ‘There was nothing in the Deed of Cession to say that when England was to hand over Fiji that it was to hand it over holus-bolus to the Fijian people and to the Fijian people alone. There was nothing whatsoever written in it and as the Fijian chiefs gave Fiji unreservedly to Great Britain, my interpretation is that if Great Britain wants to give it back she gives it back in the condition which she finds it. It does not necessarily mean that she should give it back to the Fijian people.'

The late Ratu Sir George Cakobau, on the other hand, had demanded: ‘I have nothing against independence. Let it come. But when it comes, I should like this recorded in this House-Let the British government return Fiji to Fijians in the state and same spirit with which Fijians gave Fiji to Great Britain.’

Ratu Sir George Cakobau

As the great-grandson of Ratu Seru Cakobau, the late Ratu George Cakobau was paramount chief of Fiji and the first Fijian to hold the post of Governor-General in post-independent Fiji. On 18 September 1959 he was formally invested as Vunivalu and Tui Kaba in front of more than 3000 people at Bau. The dignity and restrained emotion of the occasion emphasised its historic significance. Not for 106 years had the impressive ceremony been performed. The ceremony thus became linked with 26 July 1853, when Ratu Cakobau, later Tui Viti -Ratu George’s great grandfather-was installed. The keynote of the ceremony was set when Ratu Edward Tugi Tuivanuavou Cakobau, Ratu George’s first cousin, presented him with a tabua, pledging the Bau people’s loyalty and the loyalty of all those associated with Bau.

When the coups of 1987 made world headlines, Ratu George had been retired three years from the gubernatorial role. Efforts by followers of Dr Timoci Bavadra’s government, which had been overthrown by Sitiveni Rabuka, to solicit Ratu George’s aid in the complicated events, which split the two major races and divided families and tribes, proved unsuccessful. He however denounced Rabuka’s threats to remove his successor Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau as governor-general and impose a republic. Earlier, however, he had received Bavadra and his ministerial colleagues at the chiefly island of Bau. He indicated his support for the new inter-racial government and for the western Fijians or Melanesian Fiji and distanced himself from their traditional rivals in the Polynesian east.

This was, as Kenneth Bain wrote on Ratu Cakobau’s death, ‘the classic Fijian dynastic divide’. As Vunivalu of Fiji, Ratu George’s supremacy had never been dangerously challenged and his ancestry gave him a prime say in Fijian affairs. During the disturbances of 1959 in Suva, he warned the rioting and looting crowd who had assembled for a public meeting at Albert Park in Suva: ‘I do not want to stop your meeting. I want to speak of the damage you have done. You are not young and you know right from wrong. But whatever you do, remember the name of Fiji. The reputation of the Fijians is up to you. That is all.’

On Fiji’s independence in 1970 Ratu George was Minister for Fijian Affairs. In 1977 his statesmanship saved the political career of the first Prime Minister Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara on the defeat of his predominantly Alliance Party at the hands of the National Federation Party. He asked Ratu Mara to re-form a government which was to last until the latter’s second and serious defeat in 1987, prompting military intervention in Fiji’s politics. He was deeply saddened to see the severance of the links with the British Crown which he had so cherished because his great-grandfather was the architect of the cession. In March 1988, however, when Ratu Mara, without apparently consulting Cakobau beforehand, set off for London and Buckingham Palace, he was outraged. The purpose of Ratu Mara’s visit was to try to persuade the Queen to retain the title of Tui Viti - Queen of Fiji- which was passed to Queen Victoria by Ratu Seru Cakobau at cession in 1874.‘The title came back to me’, Ratu George said in Bau, ‘when Fiji became independent in 1970. I have no plans to abdicate. The title is not Ratu Mara’s to give away’.

The implications for an already fragmented and divided Fijian society was far-reaching, as played out during the recent the hostage crisis.

The Mara/Cakobau Dynasty

In recent years there has been a public split between the Mara/Cakobau political and traditional dynasty. The victory of the Fiji Labour Party, the inclusion of Ratu Mara’s daughter as a Minister in Chaudhry’s government, and Ratu Mara’s elevation as President of Fiji, drove a further wedge between the Mara-Cakobau clan in Fijian politics. It was not surprising, therefore, that Speight and others hailing from the Cakobau side of the traditional clan had been baying for Mara’s political blood shortly after seizing power. Unlike the Mara family, the Cakobau family had been badly defeated at the polls. As the Daily Post pointed out on 19 May 1999, a year to the day Speight and his hoodlums seized the Chaudhry government, the Cakobau family name was not enough to muster the support of Tailevu voters as brother, sister, and cousin lost their respective seats. Members of this chiefly Bau and Tailevu family, regarded highly throughout the country, could not hold on to their voting leads, and lost out after preferences were distributed. Ratu Epenisa Cakobau, Adi Litia Cakobau’s brother, lost the Tailevu South Lomaiviti open seat to political enthusiast and Fiji Labour Party candidate Isireli Vuivau. Ratu Epenisa was among those who had formed the Fijian Association Party. However, he withdrew his support from the party after his elder sister Adi Samanunu contested the 1994 elections for the SVT. ‘Family unity is very important to me’, he had said then.

The first to concede defeat was Adi Litia Cakobau, the daughter of the late Vunivalu. She had contested the Tailevu North/Ovalau open seat, a seat which my late father, as President of the Tailevu North Alliance District Council, had actively campaigned and helped Ratu George Cakobau to win in the 1970s. Adi Litia and Ratu Epenisa had contested the elections under the SVT electoral tickets. An emotional Adi Litia attributed their loss to what she described as the other Fijian parties determination to eliminate the SVT. ‘It is really sad that the other parties had preached that we had sold out the interest of Fijians. People, the Fijians, need to understand their Constitution. The rights of the indigenous is well protected. The question they should ask is what will happen now-will they be able to get extra or special protection as given to them by the SVT.’

She noted that her loss was as a result of ‘a divided Fijian front’. Adi Litia said that the ‘vanua no longer could dictate the people’s political preference but that is democracy’. ‘The people have chosen their representatives and that is what counts’, Adi Litia said. She had also moved Sitiveni Rabuka’s name for chairman of the Great Council of Chiefs, while Ratu Tevita Vakalalabure of Cakaudrove moved her name for vice chairman.

This clearly showed that the provinces of Tailevu and Cakaudrove wanted to control the Council, especially after the SVT lost power in the general elections to the People's Coalition of Labour, Fijian Association and PANU.

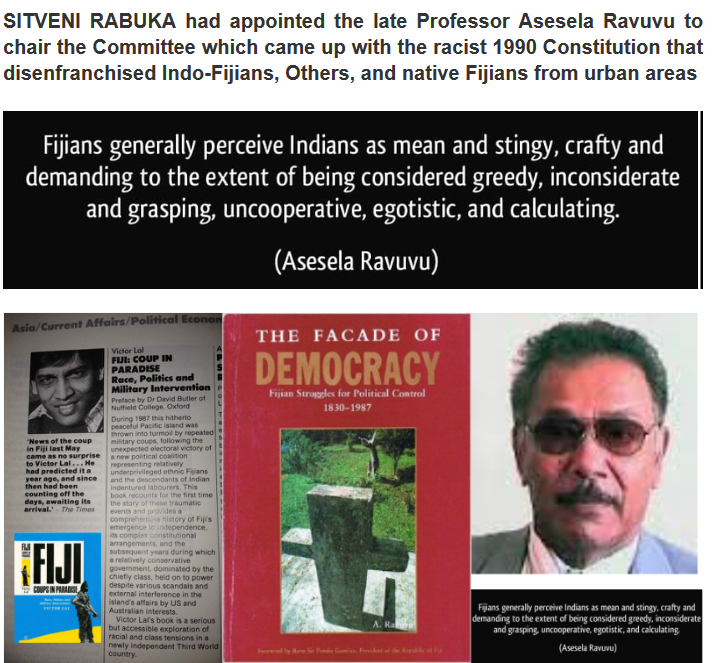

History is also repeating itself. Professor Ravuvu is asking us to wait for the birth of a new Constitution. If a Constitution emerges from such a chaotic and inexpert approach, we will have a Constitution with all the attendant problems of the ‘Bau Constitution’ of the 19th Century.

The attempted assassination of Banimarama, if it had succeeded, would have imposed on the nation another genetically modified version of Fijian leadership, and supported by a new military dictator, in the name of indigenous rights. The successful perpetrators of the coup would have claimed that the current crop of Fijians in the Interim Administration were not ruthlessly nationalistic enough in upholding Fijian rights, especially land rights. But the attempted coup failed for the second time in the new millennium because a segment of the troops loyal to Banimarama stood firmly behind their military leader. It also injected a new lease of life in the continuance of the Interim Government, and spared those running the country from suffering the same fate as the Chaudhry government. Many members of the Interim Regime, no doubt, if the attempted coup had succeeded, would have been given a bitter taste of what it was like for Chaudhry and others to be deprived of their liberty for 56 days at the hands of another pseudo saviour of the Fijian race. They would have become a new set of hostages at the hands of another George Speight, a man not in impeccably shinning wolves clothing but a military strongman in full military regalia with shinning medals proudly plastered to his chest, and repeating the words of the Father of the Coups, Sitiveni Rabuka: ‘NoOther Way.’

What is most surprising however is that, unlike the dismissal of the Chaudhry government, Bainimarama was not removed from his post, nor were the members of the Interim government, on the grounds that ‘we must accept the reality of the Fijiansituation, and accept the demands of the hardliners for the supremacy of Fijians in their own and only country’. The whole bloody and violent affair is being quietly brushed under the mat because it is in conflict with the avowed aims and objectives of some Fijians to re-introduce apartheid in Fiji. It is equally baffling to ask: why did these soldiers mutiny when they already had a Fijian leading a predominantly Fijian Interim Government, charged to draw up a new Constitution to ensure Fijian supremacy under the South Pacific sun. If Chaudhry had to be bundled out of office because he was not an authentic taukei, what was wrong with Commodre Frank Bainimarama, a high-ranking Fijian chief in his own right. The partial answer may be found in the public outburst of Bainimarama himself before the assassination attempt, that the Fijian chiefs were only united in their hatred of the Indo-Fijians. His comments, like the attempted mutiny, sent a chill down the spines of the commoner Fijians, chiefs, and those leading the Great Council of Chiefs. Coups and counter-kuttus in Fiji

What were the underlying causes of the attempted mutiny will remain a matter of conjecture and speculation for years to come. Who were the key players behind the scene will never be known. We have been however reliably informed that Sitiveni Rabuka and the Police Commissioner Isikia Savua were part of the grand conspiracy to bring down the Chaudhry government.But what we are sure of and can say with certainty is that a group of Fijians had plotted against another group of Fijians in the historical power struggle for the control of the nation. In other words, coups and counter-coups have been a regular feature of the Fijian way of life for settling disputes. One long-standing Fijian friend of mind recently tried to make a joking humour of what he acknowledged was a serious and disastrous problem for the Fijians. He wrote: ‘Whether it is Sitiveni Rabuka’s Coup 1 and Coup 11, or George Speight’s Attempted Coup 1 and the rebel soldiers Attempted Coup 11, it is inevitable that whenever a coup takes place, you can be sure that the political kuttu (head lies or neats) is ready to counter-attack our heads. In other words, one political kuttumerely takes over from another politicalkuttuthe control ofour heads, and we end up dying from lack of blood for providing our head as a fertile ground for the political kuttu to thrive politically. The kuttumoves on to his next victim. This is also true of our Indo-Fijian brethren and sisters who have to enduredifferent types of political kuttus in their own community.’On a more serious note, coups and counter-coups are not new in Fiji; it existed even before the arrival of the Indo-Fijians as indentured labourers.

Its genesis can be traced as far back to the so-called ‘Bau Constitution’ of the 19th Century which vainly tried to impose constitutional solutions to Fiji’s intricate racial, tribal, and provincial problems.

Coups, counter coups and ‘Bau Constitution’ - The Cakobau Government

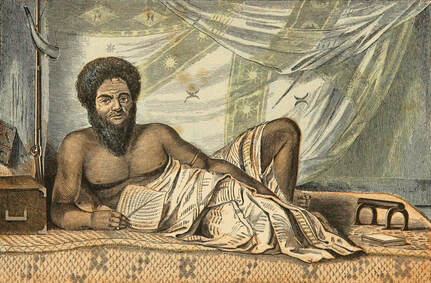

According to the records of the colonial government’s archivist, A.I. Diamond, the advent of Europeans resulted in a marked increase in the extent and ferocity of native warfare. Towards 1850, power and influence in the Fiji were beginning to centre on the chiefdoms of Bau, Rewa, Somosomo, Verata, Naitasiri, Macuata, Bua and Lakeba. Of these Bau was undoubtedly the most powerful, her chiefs having extended their influence by means of warfare, intrigue, and judicious alliances over nearly one-third of Fiji. By 1850, Cakobau had achieved a position so near to paramountcy that foreigners had begun to address him as Tui Viti (King of Fiji). Cakobau’s claim to the title was not generally recognised by Fijians outside his own dominions, and it would scarcely merit mention here were it not for the fact that it brought him later into conflict with the United States government. In 1855, the latter had brought indemnity claims against him for damage and loss of property said to have been sustained by Americans at the hands of the Fijians.

Although Cakobau himself was not personally responsible with the incidents on which the claims were based, the US government insisted that as King of Fiji, he was responsible for the actions of his subjects. The claims amounted in the end to over $45,000 (dollars), a sum which Cakobau could not hope to raise by himself, and as they were pressed with the threat of warlike reprisals the Vunivalu found himself in circumstances which could lead to his downfall.To add to his difficulties, Cakobau began to find his supremacy threatened after 1855 by the rise to power of Ma’afu. The latter, a Tongan war chief, had come to Fiji with his retainers in 1848, thirty-one years before the introduction of Indian indentured labourers to Fiji. After aiding Cakobau in a campaign against the chiefs of Rewa and their allies, Ma’afu had established himself in Lau. From there he began to extend his influence into other parts of the Group until by 1865 he controlled Beqa and large parts of the western coasts of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. Cakobau watched his rival’s activities with increasing alarm, seeing in them preparations for his own eventual subversion and overthrow. Harassed by these difficulties, Cakobau turned for advice to the British Consul, William Thomas Pritchard, who responded by urging him to offer Fiji to Great Britain. Though Cakobau had no authority to make such an offer, he in his extremity, agreed and a formal Deed of Cession was drawn up on 12 October 1858, offering Fiji to the British government on certain conditions, including the payment of the American claims in return for a conveyance of 200,000 acres of land to the British crown.

The offer was subsequently acknowledged, ratified and renewed by the Fijian chiefs on 14 December 1859. The Deed of Cession was taken to England for presentation by Pritchard himself who made vigorous efforts on arrival to ensure that the offer was favourably received. After some delay, the British government despatched a Colonel W.G. Smythe to Fiji to investigate and report on the expediency of annexation. Smythe’s report, however, was unfavourable, and in 1862 the Government of New South Wales in Australia was instructed by the British authorities to inform Cakobau and his supporters that the offer of cessionhad been declined. Shortly after this refusal Cakobau repeated the offer to the United States government. The latter, however, being engaged at the time in Civil War, sent no reply.Between 1865 and 1871 several attempts were made to introduce a measure of political stability into Fiji by means of Confederations, but for various reasons, more especially the inexperience and mutual suspicion and hostility of the leading chiefs, none of the Confederacies succeeded. In 1865 Cakobau and Ma’afu were persuaded to co-operate in the establishment of a Confederacy of the six most powerful native dominions in Fiji; these being Bau, Rewa, Lakeba, Bua, Cakaudrove, and Macuata.

The chieftains of the six, claiming to speak for the whole of Fiji, constituted themselves a General Assembly with power to legislate for a code of laws which was to be effective throughout Fiji. The members states were to retain their sovereignty, but each agreed to observe the common code of laws and to unite for the preservation of peace and order. The Confederation was inaugurated on 8 May 1865 under the Presidency of Cakobau. Much hope was entertained for the success of the venture and for the first two years it functioned well enough. But in 1867, when Ma’afu began to canvas support for himself as President of the Assembly, Cakobau and several of the leading Fijian chiefs withdrew and the Confederacy collapsed. Upon the failure of the 1865 Confederation, Ma’afu and Cakobau immediately set up institutions for the control of their own spheres of influence. Ma’afu, with the help of his European secretary, R. S. Swanston, induced the chiefs of Lau, Cakaudrove and Bua to combine under his leadership in a Confederation (the Tovata i Viti or Tovata i Lau), similar in character to the Confederation of1865. At the same time, Cakobau, urged on by the European settlers at Levuka, adopted for his own dominion the form of a European monarchy modelled on the Hawaiian Constitution.

The latter is of particular interest as it afterwards formed the basis of theso-called Cakobau Government of 1871. The Lau Confederation, under Ma’afu’s direction was moderately successful and held together until 1871. Ma’afu later assuming the title of Tui Lau. The Bau monarchy, however, collapsed within a year mainly as a result of internal dissension and lack of revenues. In 1869, an attempt was made to re-instate it under a revised constitution but it failed almost immediately and for the same reasons as its predecessor.The huge influx of White settlers during the cotton boomof the 1860s brought with it a corresponding increase in the need for stable and unified government. Hitherto the British, American and German consuls, supported by occasional visits from warships, had managed fairly effectively to protect and regulate the affairs of the European population and to mediate between their own nationals and the Fijians.

The competency of the Consuls, however, was limited and by 1870 it was clear that if the lives and property of the settlers and the interests of the natives themselves were to be secured a local government would have to be established with legislative authority over the whole of Fiji and coercive power sufficient to keep the peace and enforce the law.Fiji’s first coup Although most of the settlers were agreed in principle on the need for such a government, constant dispute between the various sections of the European population made concerted action difficult. In the end, the ‘national’ government was established by means of a coup. In the early months of 1871,a group of Levuka businessmen formed a conspiracy and approached Cakobau in secret with a proposal that he place himself at the head of a Government claiming sovereignty over the whole of Fiji. The attempt could easily have ended, like others before it, in a fiasco. This one, however, came as a complete surprise and was, moreover, well-timed. Cakobau was occupied in the successful conclusion of a campaign against the Lovoni people on the island of Ovalau. Thus not only was his prestige enhanced but that victory was turned to account by the penalty meted out to the Lovoni people.

The latter were expropriated and sold into servitude to white planters at the rate of £3 a head and a yearly hire of the same amount. The revenue from the 'hire’ of Lovoni labour was considerable and as it was placed at the disposal of the new Government the latter began, unlike its predecessors, with at least one assured source of annual income.The proclamation of the ‘Cakobau Government’, as it has come to be known, at first raised a storm of protest among the Europeans in Levuka. But opposition was greatly reduced by the publication of a ‘Gazette’ containing among other things, an undertaking by the Executive to delay the initiation of all matters other than those of urgent public necessity until a House of Representatives had been assembled. With this assurance, the majority of the settlers were content for the time being to accept the new Government as a ‘fait accompli’ and many even lent their active support to it.It was obvious to most, however, that the future of the Government depended heavily upon the reaction of Ma’afu. Ma’afu was not only the leader of a powerful alliance of chiefs, but could easily, if he chose, set himself up as the champion of the dissident elements among the Europeans.

But surprisingly enough Ma’afu offered no resistance to the coup and even agreed to co-operate with the new Government. On 22 July he visited Levuka and, in the course of discussions with Cakobau lasting two days, acknowledged him as TuiViti, took the oath of allegiance and abandoned all territorial claims outside Lau, the seat of his power. In return he was made Viceroy of Lau with salary of £800 and was given a clear title to the islands of Moala, Matuku and Totoya. The acquiescence ofMa’afu effectively disposed of the threat of serious resistance from the native Fijians and by the end of the year all the ruling chiefs had tendered their allegiance to Cakobau.The ‘Bau Constitution’The first Gazette, issued by the new Government on 5 June 1871, gave notice that Cakobau, Tui Viti, had been pleased under the Bau Constitution to appoint an Executive (mostly Europeans) consisting of the following: Sydney Charles Burt, George Austin Woods, John Temple Sagar, James Cobham Smith, Gustavas Hennings, and Ratu Savenaca and Ratu Timoci. Government Gazette No.2, published on 10 June 1871, contained explanations of the main causes which had led to the appointment of the Executive.

These were three: (a) the largely increasing European population, (b)the growing want of confidence in commercial matters, and (c) the hesitation of merchants and financial interests in the colonies to deal with investments in Fiji until a form of government should be adopted. The Gazette also gave notice that delegates from all the districts in Fiji had been summoned to meet at Levuka on 1 August to discuss and amend the Constitution of 1867. The House of Delegates met under the chairmanship of J.S. Butters, the former mayor of Melbourne and Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Victoria, and after two weeks deliberation, passed the Constitution Act of Fiji, 1871. This Act was signed by Cakobau on 18 August and came into force on the 1 October. The first Parliament of the Cakobau Government was opened by Cakobau on 3 November 1871. It sat until the 17 December, having passed about 20 ‘Bills’.

The Second Coup Attempt

By March 1872 there was evidence of growing distrust of, and lack of confidence in, the Government. Much jealousy was displayed over ministerial and public service appointments, and there was widespread complaint at what was described as ‘the absurd attitudes and arrogant bearing’ adopted by certain Ministers towards the public. The task of the Cakobau Government was further hampered by the effects of an economic recession resulting from the collapse of the market for ‘sea-island’ cotton. Many of the white settlers suddenly found themselves in acute financial distress and resistance to taxation increased. Revolutionary movements became active and on one occasionan armed insurrection inspired by an organisation calling itself the ‘Ku-Klux-Klan’ very nearly succeeded in overthrowing the Government. The fact that the Government survived this threat largely as a result of assistance offered by a British man-of-war did little to enhance its stature in the eyes of the public. Resistance to the Government at length resolved itself into a demand for the dissolution of the Assembly, the holding of a new election, and the dismissal of the Premier, S.C. Burt. On 18 March the Cakobau government yielded and Burt resigned. Cakobau invited J.B.Thurston, a white Tavenui planter and one of the members of the Legislative Assembly for Tavenui district, to join the Government and the latter, upon accepting the invitation, acted as Premier in the absence of G.A. Woods, who was originally chosen for the post but who was away in Australia at the time.

The third and last session of the Legislative Assembly sat between 31 May and 12 June 1873. The principal business set down was the amendment of the Constitution Act of 1871, the operation of which had been found too expensive and cumbersome. Of the 28 members of the Assembly, only 14 attended, and of these only 5 were minority, the Government were defeated and the Cabinet accordingly resigned. Cakobau, however, declined to accept, and instead issued a Proclamation dissolving the Assembly. The Assembly never sat again and thereafter administration continued under Ministerial direction until the establishment of an Interim Government on 23 March 1874.

A general election was due to be held in 1873; but at a meeting of the King-in-Council held on 29 July 1873, at Nasova, Levuka, it was resolved that the arrangements for the election should be abolished. On 11 July 1873 Cakobau appointed a RoyalCommission to revise, consolidate and amend the laws. The Commission drew up the so-called ‘National Constitution and Fundamental Laws of the Kingdom of Fiji, 1873’, and though it received the assent of Cakobau it was never adopted, owing largely to the opposition of Commodore Goodenough and the British Consul, E.L. Layard. Throughout 1872 and 1873 resistance to the Cakobau Government, particularly on the part of the Europeans, increased. In Ba, the settlers staged a revolt and again the Government found itself obliged to accept the intervention of a British warship. By the middle of 1873 the administration was facing bankruptcy and it was clear even to its supporters that the regime could not last. Responsible elements among the European community began topress for cession of Fiji to Great Britain or the United States.

The Cession of Fiji to Great Britain

On 17 March 1874, the British Consul gave warning in a public notice that the Cakobau Government was bankrupt and cautioned all British subjects againstallowing the Government further credit. The notice further declared that British subjects accepting or retaining official posts in the Armed Constabulary were liable to prosecution under the UK Foreign Enlistment Act. The Consul’s action practically put an end to the attempt at self-government, and the newly formed Ministry strongly advised Cakobau to reconsider the question of annexation by Great Britain. A meeting of the leading Fijian chiefs was held in March, and the 21stof that month a formal offer of cession was made to the Commissioners who communicated it to the Imperial government in London.

At the meeting, held at Levuka on 23 March 1874, attended by the Commissioners, Cakobau and other high chiefs, the foreign Consuls, the Chief Secretary Thurston and the Chief Justice (St Julian), it was resolved that an Interim Government should be established to carry on the administration of Fiji pending a decision by the Imperial government on the subject of annexation.The offer of cession made on 21 March,contained terms which proved unacceptable to the British government and as a result, Sir Hercules Robinson, then Governor of New South Wales, was despatched to Fiji in September 1874, to negotiate. On 30 September Robinson telegraphed Lord Carnarvon in London: ‘The King (Thakombau) has this day signed an unconditional cession of the country. I am leaving today on a tour to obtain the signature of Ma’afu and other ruling Chiefs’. His mission was successful and on 10 October Cakobau, Ma’afu and other principal chiefs ceded the sovereignty of Fiji to Great Britain. Upon the conclusion of the Deed of Cession, Sir Hercules Robinson established a Provisional Government to carry on administration until the arrival of the Governor and the Proclamation of the Colony.

The administration of the Provisional Government terminated on the 1 September 1875, with the proclamation of the Royal Charter erecting Fiji into a separate Colony and with the assumption of office of the first resident Governor, Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon, the man responsible for introducing Indian indentured labourers into Fiji in 1879. Gordon was safeguarding the Fijian population as they were still struggling to fight off an epidemic of measles in 1875 which had killed about 40,000 of the estimated population of 150,000 Fijians. The epidemic occurred after Cakobau and his two sons, who had contracted mild cases of measles during their return voyage from a visit to Sydney, were allowed to land in Fiji before they had completely recovered. Responsibility for the disaster rested with the captain and medical officer of H.M.S Dido. They failed to impress upon E.L. Layard, the British consul for Fiji and Tonga, the serious consequences that might result from failure to place the patients in quarantine.

The Deed of Cession

King Cakobau had sent Queen Victoria a basket of earth to symbolise the handing over of the land of Fiji and his oldest and favourite war club. This latter item was later returned to Fiji by King George V where, topped with a silver crown and a dove of peace, it became the mace of the Legislative Council and subsequent Parliaments of Fiji. The Deed of Cession has been regarded as the charter of Fijians indigenous rights. It has been appropriated by Fijians of different political persuasions for different purposes. It is worth remembering that it was mostly the eastern chiefs who had made an unconditional cession of their islands to Great Britain. As Governor Sir Ronald Garvey noted in his Cession Day’s speech in 1957, ‘to read into the Deed more than that, to suggest, for instance, that the rights and interests of the Fijians should predominate over everything else, does not service either to the Fijian people or to their country’.

The adoption of that view, Sir Ronald continued, ‘would mean complete protection and no-self-respecting individual race wants that because, ultimately, it means that those subject to it will end up as museum pieces’. The late Ratu William Toganivalu, a high chief and Cabinet Minister in the Alliance Government, had argued in the House of Representatives in June 1970: ‘There was nothing in the Deed of Cession to say that when England was to hand over Fiji that it was to hand it over holus-bolus to the Fijian people and to the Fijian people alone. There was nothing whatsoever written in it and as the Fijian chiefs gave Fiji unreservedly to Great Britain, my interpretation is that if Great Britain wants to give it back she gives it back in the condition which she finds it. It does not necessarily mean that she should give it back to the Fijian people.'

The late Ratu Sir George Cakobau, on the other hand, had demanded: ‘I have nothing against independence. Let it come. But when it comes, I should like this recorded in this House-Let the British government return Fiji to Fijians in the state and same spirit with which Fijians gave Fiji to Great Britain.’

Ratu Sir George Cakobau

As the great-grandson of Ratu Seru Cakobau, the late Ratu George Cakobau was paramount chief of Fiji and the first Fijian to hold the post of Governor-General in post-independent Fiji. On 18 September 1959 he was formally invested as Vunivalu and Tui Kaba in front of more than 3000 people at Bau. The dignity and restrained emotion of the occasion emphasised its historic significance. Not for 106 years had the impressive ceremony been performed. The ceremony thus became linked with 26 July 1853, when Ratu Cakobau, later Tui Viti -Ratu George’s great grandfather-was installed. The keynote of the ceremony was set when Ratu Edward Tugi Tuivanuavou Cakobau, Ratu George’s first cousin, presented him with a tabua, pledging the Bau people’s loyalty and the loyalty of all those associated with Bau.

When the coups of 1987 made world headlines, Ratu George had been retired three years from the gubernatorial role. Efforts by followers of Dr Timoci Bavadra’s government, which had been overthrown by Sitiveni Rabuka, to solicit Ratu George’s aid in the complicated events, which split the two major races and divided families and tribes, proved unsuccessful. He however denounced Rabuka’s threats to remove his successor Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau as governor-general and impose a republic. Earlier, however, he had received Bavadra and his ministerial colleagues at the chiefly island of Bau. He indicated his support for the new inter-racial government and for the western Fijians or Melanesian Fiji and distanced himself from their traditional rivals in the Polynesian east.

This was, as Kenneth Bain wrote on Ratu Cakobau’s death, ‘the classic Fijian dynastic divide’. As Vunivalu of Fiji, Ratu George’s supremacy had never been dangerously challenged and his ancestry gave him a prime say in Fijian affairs. During the disturbances of 1959 in Suva, he warned the rioting and looting crowd who had assembled for a public meeting at Albert Park in Suva: ‘I do not want to stop your meeting. I want to speak of the damage you have done. You are not young and you know right from wrong. But whatever you do, remember the name of Fiji. The reputation of the Fijians is up to you. That is all.’

On Fiji’s independence in 1970 Ratu George was Minister for Fijian Affairs. In 1977 his statesmanship saved the political career of the first Prime Minister Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara on the defeat of his predominantly Alliance Party at the hands of the National Federation Party. He asked Ratu Mara to re-form a government which was to last until the latter’s second and serious defeat in 1987, prompting military intervention in Fiji’s politics. He was deeply saddened to see the severance of the links with the British Crown which he had so cherished because his great-grandfather was the architect of the cession. In March 1988, however, when Ratu Mara, without apparently consulting Cakobau beforehand, set off for London and Buckingham Palace, he was outraged. The purpose of Ratu Mara’s visit was to try to persuade the Queen to retain the title of Tui Viti - Queen of Fiji- which was passed to Queen Victoria by Ratu Seru Cakobau at cession in 1874.‘The title came back to me’, Ratu George said in Bau, ‘when Fiji became independent in 1970. I have no plans to abdicate. The title is not Ratu Mara’s to give away’.

The implications for an already fragmented and divided Fijian society was far-reaching, as played out during the recent the hostage crisis.

The Mara/Cakobau Dynasty

In recent years there has been a public split between the Mara/Cakobau political and traditional dynasty. The victory of the Fiji Labour Party, the inclusion of Ratu Mara’s daughter as a Minister in Chaudhry’s government, and Ratu Mara’s elevation as President of Fiji, drove a further wedge between the Mara-Cakobau clan in Fijian politics. It was not surprising, therefore, that Speight and others hailing from the Cakobau side of the traditional clan had been baying for Mara’s political blood shortly after seizing power. Unlike the Mara family, the Cakobau family had been badly defeated at the polls. As the Daily Post pointed out on 19 May 1999, a year to the day Speight and his hoodlums seized the Chaudhry government, the Cakobau family name was not enough to muster the support of Tailevu voters as brother, sister, and cousin lost their respective seats. Members of this chiefly Bau and Tailevu family, regarded highly throughout the country, could not hold on to their voting leads, and lost out after preferences were distributed. Ratu Epenisa Cakobau, Adi Litia Cakobau’s brother, lost the Tailevu South Lomaiviti open seat to political enthusiast and Fiji Labour Party candidate Isireli Vuivau. Ratu Epenisa was among those who had formed the Fijian Association Party. However, he withdrew his support from the party after his elder sister Adi Samanunu contested the 1994 elections for the SVT. ‘Family unity is very important to me’, he had said then.

The first to concede defeat was Adi Litia Cakobau, the daughter of the late Vunivalu. She had contested the Tailevu North/Ovalau open seat, a seat which my late father, as President of the Tailevu North Alliance District Council, had actively campaigned and helped Ratu George Cakobau to win in the 1970s. Adi Litia and Ratu Epenisa had contested the elections under the SVT electoral tickets. An emotional Adi Litia attributed their loss to what she described as the other Fijian parties determination to eliminate the SVT. ‘It is really sad that the other parties had preached that we had sold out the interest of Fijians. People, the Fijians, need to understand their Constitution. The rights of the indigenous is well protected. The question they should ask is what will happen now-will they be able to get extra or special protection as given to them by the SVT.’

She noted that her loss was as a result of ‘a divided Fijian front’. Adi Litia said that the ‘vanua no longer could dictate the people’s political preference but that is democracy’. ‘The people have chosen their representatives and that is what counts’, Adi Litia said. She had also moved Sitiveni Rabuka’s name for chairman of the Great Council of Chiefs, while Ratu Tevita Vakalalabure of Cakaudrove moved her name for vice chairman.

This clearly showed that the provinces of Tailevu and Cakaudrove wanted to control the Council, especially after the SVT lost power in the general elections to the People's Coalition of Labour, Fijian Association and PANU.

History is also repeating itself. Professor Ravuvu is asking us to wait for the birth of a new Constitution. If a Constitution emerges from such a chaotic and inexpert approach, we will have a Constitution with all the attendant problems of the ‘Bau Constitution’ of the 19th Century.