"For many Indo-Fijian voters, the NFP’s, and in particular its leader, Jai Ram Reddy’s, achievements on the promulgation of the 1997 Constitution and talk of racial harmony were abstract issues. Also, the coalition with Rabuka’s SVT was insignificant. As Sir Vijay Singh put it, ‘In restoring the democratic constitution’, Rabuka ‘did the Indians no favour’. He ‘restored what he had stolen in the first place’. |

The FATAL EMBRACE - Part Two from Fiji's Daily Post, 2000:

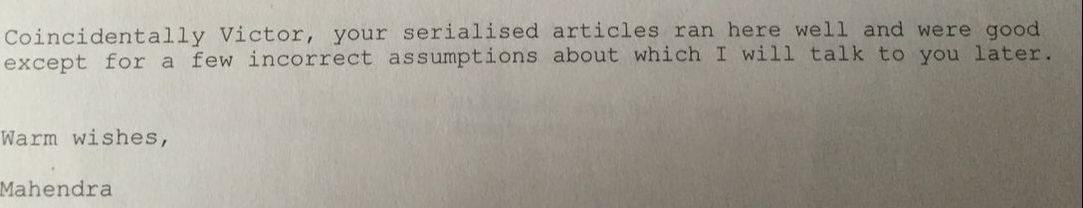

| By VICTOR LAL FLP and Strength of its Multi-Racialism ONE of the greatest strengths of Mahendra Chaudhry and the Fiji Labour Party (FLP), of which he was one of the original co-founders, was their politics of multi-racialism. An analysis of the results of the elections under the previous first-past-the post voting system would show that the FLP would have won the majority of seats to form a government of its own choice and complexion. But in the May general elections the party made a fatal political mistake by embracing the splinter Fijian political parties into its fold to form a Peoples Coalition during the run-up to the elections. We have already dealt with the VLP. Whoever was advising Chaudhry and the FLP had not immersed himself/herself into the impetuous character of Fijian history and politics. Like his political foes in the NFP (Notoriously Faction-Ridden Politicians), the Fijians in the People's Coalition had convinced themselves that it was only in the company of the FLP that they could find new jobs as Ministers and Backbenchers. Some Fijian politicians were merely using the coalition with the FLP to achieve their dreams of becoming Prime Minister of Fiji after the May elections. Having demolished the once invincible and faction-ridden NFP, as well as the chiefly sponsored and Sitiveni Rabuka led SVT, Chaudhry however found himself chained to a new 1997 Constitution with its mandatory provision for power sharing, entitling any political party with more than 10 per cent of the seats in the Lower House to a place in Cabinet (in proportion to its percentage of seats). | https://www.fijileaks.com/home/replaying-history-mahend-chaudhry-was-a-misguided-saint-flanked-by-political-racist-devils-in-the-peoples-coalition-government-in-1999 |

The party with the most number of seats provided the Prime Minister, who allocated portfolios in Cabinet. Because of this provision for a multi-racial cabinet, the parties in the People's Coalition formed only a loose coalition among themselves, leaving the details of power sharing and leadership to be decided after the elections. More importantly, the politics of race was, for once, relegated to the background because both the coalitions, the People's Coalition and the SVT/NFP/GVP Coalition were multi-racial in character, at least for electoral purposes.

Mahendra Chaudhry Charms

and Slarms i-Taukeis

It is no secret that disgruntled Fijian politicians under the guise of Taukeism played a leading role which set the stage for George Speight and his henchmen to overthrow the Chaudhry government. Land and race was mixed with politics, even though these sensitive issues were not on the voters minds.

A Tebbutt Research on behalf the Fiji Times in April 1999 revealed that 26% of the voters thought unemployment was the most important issue in the election (Fijians 30% and Indo-Fijians 23%); followed by land issues/ALTA (14% -Fijians 8% and Indo-Fijians 21%).

According to SVT official Jone Dakuvula, a SVT-inspired agitation and destabilisation against Chaudhry began almost immediately after Chaudhry’s win. Jim Ah Koy, who was Finance Minister in Sitiveni Rabuka’s last government, while distancing himself from Speight’s take-over of Parliament, said he understood the Speight’s groups frustration and anger. He blamed the Chaudhry government’s ‘arrogance and obduracy in not listening to the sensitivities of the indigenous Fijians’.

Chaudhry sought to introduce a Land Use Commission to restructure land ownership

On 3 April 2000, based on World Bank Report and other reputable sources, Chaudhry declared Fiji would remain poor as long as the land remained underdeveloped. That ‘development’ required larger plantations and more secure titles in order to attract investment. Chaudhry also offered small Indo-Fijian growers $28,000 each to leave their farms and proposed that leases be extended for 60 years at the current low rents. Both the Council of Chiefs and the NLTB opposed these measures, accusing Chaudhry of favouring the Indo-Fijian tenant farmers and undermining the Council of Chiefs. Ironically, as the plight of the Indo-Fijian farmers worsens, with frightening consequences for the econony in general, the Interim Administration has agreed to pay the displaced farmers $28,000 or less depending on their circumstances.

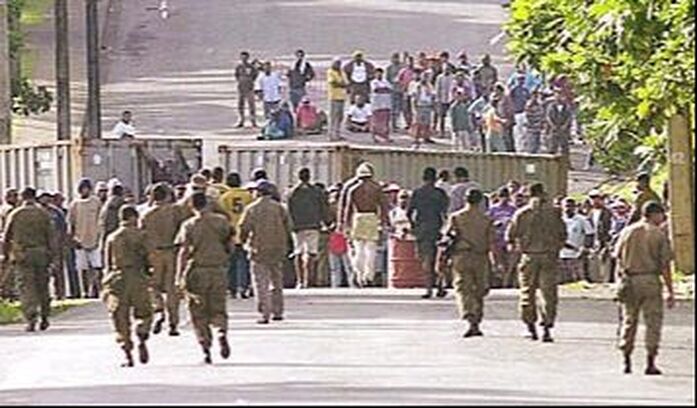

On the day of Speight’s coups, about 5,000 people marched through Suva, demanding Chaudhry’s removal, following a similar march on 28 April. Marchers denounced the Government’s planned changes to land use, accusing it of moving to ‘usurp land’ from native landowners. They also attacked Chaudhry for showing ‘disrespect’ for the Council of Chiefs. The marches were called by the Fijian chauvinist Taukei Movement and led by Apisai Tora, who lost his parliamentary seat in the general elections. Tora revived the Taukei, which also staged marches and carried out racial attacks on Indo-Fijian citizens and politicians as a prelude to the 1987 coups. SVT secretary Jone Banuve gave his endorsement to Speight as he entered the besieged Parliament to meet him. He also issued a statement in the SVT’s name, saying: ‘We will never accept the reinstatement of the Chaudhry, nor any non-Taukei leadership’.

The SVT’s parliamentary leader, Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, said he knew nothing about the statement.Whether or not Kubuabola, the principal architect of the 1987 coups, knew of the statement, most of the Fijian politicians and leaders were attempting to leverage favourable outcome. While Sitiveni Rabuka issued a statement saying there should be ‘no amnesty’ for Speight and his followers, his ambiguous position was summed up in comments to the media: ‘I sympathise with your [Speight’s] cause, but I don’t agree with your methods.’ Tora, like Rabuka, said he sympathised with the cause but did not approve ofthe methods. He said the Taukei Movement had its own plan which he says was a much more logical approach. Chaudhry, on the other hand, had impressed and charmed even some of the die-hard Taukei members with his leadership qualities. Taukei activist Sivoki Mateinaniu said members of the Taukei Movement and Fijian politicians should learn from Chaudhry. ‘Mr Chaudhry’s policies are simple. He is just trying to implement what he promised; unlike the SVT government who forgot its election promises as soon as they were elected. Now the Fijians are still confused because our so-called leaders forgot to protect us in the [1997] Constitution. They did not even formulate legislation to protect our cause’, Mateinaniu said. ‘In the 1999 elections, they could not promise the Fijians anymore because they had failed to deliver in 1992 and 1994’. He called on Fijians not to listen to the hollow calls to disrupt stability and good governance. ‘The Taukei Movement now supports Mahendra Chaudhry’.

Chaudhry: Emperor Without the Prime Ministerial Robe

It was a remarkable transformation on Mateinaniu’s part and an honest and accurate assessment of Chaudhry’s leadership qualities. As the veteran politician and political commentator Sir Vijay Singh observed that, ‘Of all the major political parties, Mahendra Pal Chaudhry alone retained a clear vision of his party’s constituency-workers and farmers, the poor, and the deprived’ of all the races in Fiji’. Furthermore, the FLP had an extensive network to communicate that message. The Fiji Public Service Association, of which Chaudhry was the head, reached out to the public sector. He was also able to galvanise the farming community through the National Farmers Union, of which he was the head. The Labour candidate, Pratap Chand, as head of the Fiji Teachers Union, was able to reach out to primary and secondary teachers who play an educative role in our muti-racial community.

Sir Vijay R Singh: 'In restoring the democratic constitution, Rabuka did the Indians No Favour'

For many Indo-Fijian voters, the NFP’s, and in particular its leader, Jai Ram Reddy’s, achievements on the promulgation of the 1997 Constitution and talk of racial harmony were abstract issues. Also, the coalition with Rabuka’s SVT was insignificant. As Sir Vijay put it, ‘In restoring the democratic constitution’, Rabuka ‘did the Indians no favour’. He ‘restored what he had stolen in the first place’. The FLP also promised policies and initiatives of its own: the removal of the 10% Value Added Tax (VAT) and Customs Duty from basic food and educational items, review taxation on savings and raise allowances for dependants, provide social security for the aged and destitute, and lower interest rates on housing loans.The FLP had caught the peoples imagination. It was ‘Time for a Change’. And it was indeed a refreshing political change of scene.

The voters of Fiji elected by a landslide the ‘People's Coalition’ consisting of the FLP, the Party of National Unity (PANU) and the Fijian Association Party (FAP), with Labour winning 37 of the 71 seats, enough to govern on its own. However, it was the beginning of the end of Chaudhry’s government. The root and arguably the most significant cause of the demise of the Chaudhry government was not the Taukei Movement marches, the puppeteer George Speight and his financiers or Chauhdry’s arrogancebut (i) the provisions of 1997 Constitution of Fiji, and (ii) the non-Fiji Labour Party Fijian politicians in the ‘People's Coalition’. At the end of the day, these Fijian politicians had entered the government not on the platform of multi-racialism but as representatives of the various fractious Fijian political parties. They had racial and communal outlooks both in history and their pronouncements.

The Constitution and the election results had left the other half of the Fijians to brood, sulk, make political, provincial and tribal alliances, and plot or if necessary, to club their way back to political power under the guise of indigenous rights. Chaudhry had inherited a ‘Divided House of Representatives’ and as a result his antagonists were able to run through and occupy it illegally. He became a ‘Fall Guy’. Race and not tribalism triumphed on that fateful day, 19th of May 2000. The failed coup was executed to effectively oust his Fijian Association Party (FAP) and other Fijian guests from the House, who should not have been invited as his honoured guests in the first place under the 1997 Constitution. Chaudhry-the King Maker-had overnight become an Emperor Without the Prime Ministerial Dhoti (Indian sarong). The 1997 Constitution, with its provision for multiparty government, had made him both the victor and the vanquished.

His political gurus also slavishly allowed him to be dictated by Ratu Mara in the formation of his new government. As we have already pointed out, Chaudhry was caught with his Indian night political dhoti down in the company of ‘liu muri’ Fijian political bedfellows. Pre and post-cession Fijian history was repeating itself. The new Constitution had brought Fijian political quarrels to the Fiji Labour Party’s doorsteps. Chaudhry, the ‘misguided saint’, foolishly opened the political and multi-racial gate to his FLP-led government and in the process the ‘devils’ ignominiously and unceremoniously bundled him out of the political kingdom. ‘The King is Now Politically Dead but the Memory of Fijian Infighting Still Lives On’.

The Fijian Seeds of Chaudhry’s Troubles and Downfall

A general election was held over the period 23-30 May 1992, and one was held in February 1994. The new 1990 Constitution was overtly racist and biased in favour of Fijians. In the new 70 seat Parliament, Fijians were allocated 37 seats, Indo-Fijians 27, General Voters 5 and Rotumans 1. The Senate had 24 seats for Fijians, 9 for other races and 1 for Rotumans. In addition, all the key government posts-the presidency, prime ministership and heads of the judiciary, military, public service-had to be held by Fijians. A quota of at least 50 per cent Fijians was set for new recruitment into the public service. Another important feature of the distribution of Parliamentary seatswas the gerrymandering of the 37 Fijian constituencies because many urban Fijians had voted for Bavadra’s government in the 1987 elections. Thus rural Fijian voters were given 32 constituencies with the remaining 5 going to urban Fijian voters.The 1992 Elections With the new Constitution promulgated and Fijian political supremacy guaranteed, the first general election was held in 1992.

The principal parties that entered the election contest were: SVT, FLP, NFP, General Voters Party (GVP) and the Fijian Nationalist United Front (FNUF). Meanwhile, the NFP-FLP Coalition had split up following the death of Dr Timoci Bavadra. The FNUF, led by the late Sakiasi Butadroka, was a coalition of extremists from Fijian nationalist party (FNP) and SVT, which was formedin March 1991 with Rabuka as its political leader. The SVT had the backing of the Great Council of Chiefs. The SVT was not necessarily a unified political group and the real issue for the party was who was to become Prime Minister after the election: the ‘Father of the Coups’ Sitiveni Rabuka or the reliable, safe, moderate but right-wing Josevata Kamikamica? The political divisions within the Indo-Fijians, who are ‘All Chiefs and No Indians’, was not surprising. As the old coolie saying goes: ‘You put two Indians on a desert island and on your return next day to pick them up, you will find they have become three Indians.’ The FLP, led by Chaudhry, initially threatened to boycott the elections, stating that taking part would be tantamount to endorsing the 1990 ‘racist constitution’. However, at the last minute, the FLP leaders changed their stance and contested the election.

The result of the 37 Fijian seats were as follows: SVT 30, FNUF 5 and the last 2 went to Independents. The 27 Indo-Fijian seats were equally shared: the NFP won 14 and the FLP the other 13. The GVP won the 5 seats. The election results created the inevitability of a Coalition government. Although the SVT was theoretically in a position to form a coalition government, Rabuka was not assured of the coveted Prime Ministership. Some newly-elected SVT parliamentarians had thrown in their lot with Rabuka’s arch political rival, Josevata Kamikamica, a former Finance Minister in the pre-election Interim Government. Rabuka appeared to have 18 votes with Kamikamica only two, Filipe Bole four, and Ratu William Tonganivalu three. However Bole, Rabuka’s former teacher, freed his votes to allow them to support the majority-holder, in this case Rabuka who needed 36 confirmed votes from those who now held seats in the new House to grab the post of Prime Minister.

He went to the Government House asking President Ratu Penaia Ganilau to appoint him as Prime Minister, declaring that he had 42 votes. Ganilau asked Rabuka to demonstrate his support with accompanying signatures to confirm the numbers. Ganilau also was acutely aware that that another high-ranking chief, Ratu Mara, and a number of SVT personalities had been backing Kamikamica. In a cruel twist of irony, both the rival factions of the SVT began to court support from the NFP and FLP, the very parties deposed to ensure Fijian political supremacy in perpetuity. The SVT, formed to unify the Fijian people, could not agree on who should be its parliamentary leader. Rabuka was shocked to learn that Kamikamica had cut a deal with the veteran Indo-Fijian lawyer and politician Jai Ram Reddy and the NFP, and as a result Kamikamica had 30 votes to Rabuka’s 26. In desperation, the desperately power-hungry Rabuka, who had imprisoned Chaudhry twice, and had terrorised him and his family since 1987, shamelessly turned to the FLP leader for his political survival. But first Rabuka had to be humbled and humiliated, and reminded that power flows from the fountain of a ball point pen and not from the barrel of a Fiji Military Forces gun with a sticker reading, ‘God Loves You’.

Rabuka Scrambles to Form Government but Biltes Bullet and Begs for Chaudhry's Support

So Chaudhry and the FLP laid down the conditions for their support for Rabuka: a review of the Constitution; repeal of several controversial labour decrees, scrapping of the Value Added Tax (VAT) and land tenure reforms. The so-called Methodist preacher, a decorated solider, and a cynically pragmatic Fijian nationalist Rabuka, who desperately needed Chaudhry’s 13 historical votes, agreed to sign a letter committing himself to a deal with the FLP. The letter read: ‘I acknowledge the proposed outlined in your letter (2 June) delivered this morning. I have considered your proposals favourably and agree to take action on these issues, namely the constitution, VAT, labour decree reforms and land tenure on the basis suggested in your letter. I agree to hold discussions on the above issue in order to finalise the machinery to progress the matter further.’ In return, he got Chaudhry’s 13 votes to take him well in excess of his required 36 for the post of Prime Minister. The FLP however informed Rabuka that it would not be part of the governing coalition. Desperate to remain Prime Minister, Rabuka had accepted all the conditions in writing, only to dishonour them on resuming power. He had managed to secure thesupport of the GVP, the Rotuman representative Paul Manueli, his former army commander, and 2 independents.

A Deal with the Devil: Rabuka Betrays Agreement With Chaudhry

Now he had the numbers and the prime ministership in his sulu, Rabuka backed away from the agreement with the FLP. A spokesman of his insisted that all Rabuka had agreed to do was to discuss the issues that had been raised. There was, he stated, no agreement to do any more than this. As his official biographer John Sharpham recently put it, ‘Rabuka had already learned the art of political double speak (what we in Fiji call aage pichie or liu muri) and was prepared to walk a precarious path to stay in power’.

King Maker makes ‘Deal with the Devil’

What about Chaudhry who had done a deal with Rabuka and delivered him and a faction of the SVT the primeministership? When Chaudhry was asked if he had done ‘a deal with the devil?’ he responded: ‘No, there was no deal; the fact is we laid down conditions’. He also acknowledged the irony of the situation between the jailed and the jailor. ‘Oh, yes’, he responded when asked, ‘we hope we can enjoy that type of irony, which does not happen very often’.Chaudhry clearly relished the role of king-maker where an Indo-Fijian was called upon to arbitrate and settle question of leadership in the chiefly sponsored SVT.

It is surprising that the SVT had not run to the Great Council of Chiefs, whom they have recently elevated as the guardians of Fijian political aspirations, to settle the question of political leadership within their own ranks.. Meanwhile Kamikamica continued, in a typical Fijian fashion, to harbour his political ambitions against Rabuka. He refused to enter the post-1992 election Rabuka Cabinet, feeling that he would have been a better Prime Minister. Rabuka’s political woes however continued to shadow him in office, notably the ‘Stephen Affair’. Rabuka managed to ward off Chaudhry and his colleagues threatened withdrawal of Labour’s support for him by forming an inter-parliamentary committee to recommend appropriate machinery for considering changes to the 1990 Constitution.

In December 1992 he caused a stir in his own party and a surprise by proposing consideration of a government of national unity (GNU). According to Sharpham, ‘In March 1993 the government sent a paper on the concept to the Great Council of Chiefs, saying that the proposed government of national unity should be considered, but underplayed it as being of major importance. Mara, with other chiefs, questioned the need for such a government, and he led many chiefs who felt the idea had little merit. The chiefs decided to send it out to the provincial councils for their reaction, a move that was designed to quietly bury Rabuka’s proposal. This move was seen by some, to be aided and abetted, it has to be said, by some of the prime minister’s senior colleagues and advisors’. The SVT, and the Caucus complained at not having been consulted. Reddy half-heartedly wondered about numbers and representation. ‘We should have a figure’, he said, ‘that bears some resemblance to their [Indo-Fijian] numbers, contribution and work, and just not a token number’.

On the Indo-Fijian political front, the rivalry between the NFP and FLP intensified to the benefit of the NFP. In October 1993 the NFP candidates had roundly defeated their FLP Indo-Fijian candidatesin the municipal elections. The FLP had also fallen out with Rabuka in 1993 when he did not honour his promises in return for the FLP’s support for the premiership in 1992. On the Fijian political front, politics essentially still revolved around Rabuka and his political foe, Kamikamica. Rabuka’s critics seized the adverse aspects of the Report into the ‘Stephens Affair’ and called for his resignation. Rabuka brushed aside the resignation calls and even survived a motion of no-confidence in him. However, six Fijian MPs including Kamikamica, and David Pickering from the GVP, finally succeeded in their dogged pursuit to get rid of Rabuka when they voted with the Opposition against his budget 36-33 (with one abstention). The dissidents had hoped that Mara might either appoint Kamikamica or Ratu William Tonganivalu to form a new government. Instead, Rabuka exercised his constitutional right to dissolve his government and call for new elections.

The 1994 Elections and Fijian Divisions

It was the second general election under the new racist Constitution promulgated in 1990 after the two military take-overs in 1987 by Sitiveni Rabuka. The election was notable for the fact that the incumbent Prime Minister Rabuka was not expected to do well as dissidents in his party had broken away to form new political parties to challenge his rule. Fiji had undergone several changes prior to the 1994 elections. The President, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, had passed away, and the Great Council of Chiefs had elected Ratu Mara as his successor. The 1994 election campaign was dominated by intra-ethnic instead of inter-ethnic issues and conflicts and debates centred around communal issues because each group was fighting for communal seats. For the Indo-Fijians, the central issue of the racially biased constitution took a back seat to FLP/NFP rivalry, most of it at a personal level between Chaudhry and Reddy. Chaudhry and the FLP were repeatedly taunted by the NFP for their support for Rabuka in the aftermath of the 1992 election. The NFP claimed that the support had yielded nothing. The FLP, on the other hand, accused the NFP for being too close to Rabuka, who unwittingly reinforced this image when he announced that he planned to set up a government of national unity with Reddy after the elections.

FLP also attacked NFP for being an ‘Indian’ party as opposed to FLP’s multi.racial character. On the Fijian side, Kamikamica hastily launched a new political party, Fijian Association Party (FAP) to challenge Rabuka and the SVT. The FAP had the tacit support of the President Mara who had openly expressed his support for Kamikamica for the premiership at the Great Council of Chiefs but he was outvoted, in part by Rabuka’s politicised nominees on the Council. The SVT also condemned Kamikamica of helping to hand political power back to the Indo-Fijians. Kamikamica, on the other hand, played right into the hands of SVT nationalists when he made the strategic mistake of announcing that he would form a coalition government with the Indo-Fijians if he won the 1994 elections. He had promised to restore integrity and dignity to Fijian leadership.

Apisai Tora-Adi Kuini Join Fray

The already fragmented Fijian populace had the spectre of dealing with two other political entrants in the election-Apisai Tora and Adi Kuini Vuikaba-Speed, widow of the deposed premier Bavadra, and the remarried wife of the Australian political consultant Clive Speed. Tora, who has been a member of every political party in Fiji, this time formed his own All National Congress(ANC), which did not win a single seat in the 1992 election. He solicited votes on a platform of multi-racialism (yes!) and the exclusion of the Great Council of Chiefs from politics. At his political side was Adi Kuini. Earlier she had announced her retirement from active politics but she attempted a comeback as a candidate for the ANC. Another candidate for the ANC was David Pickering, who had defected from the GVP. At the end of the day the issue among the Fijians and Indo-Fijians revolved around leadership: did they want Rabuka over Kamikamica and Reddy over Chaudhry? The election results were interesting. The NFP won an extra 6 seats to increase its MPs to 20. There was also an increase of 5% of Indo-Fijian vote for it. The FLP only managed to win 7 seats. The results suggested that Indo-Fijians preferred Reddy’s cautious and moderate approach to Chaudhry’s often confrontational approach.

The Indo-Fijian voters were also not ready for Chaudhry’s politics of multi-racialism. Among the General Voters, the GVP managed to retain the four seats with the fifth going to Pickering. Tora and Adi Kuini were comprehensively beaten at the polls.The SVT and Rabuka managed to hold on to power by one seat, increasing their seats to 31.

In terms of voting percentages, SVT’s vote actually dropped 4%. The SVT’s Deputy Prime Minister, Filipe Bole, lost his seat to FAP’s candidate Ratu Finau Mara in the Lau constituency, where his father is the hereditary chief of Lau.The FAP only managed to win 14% of the Fijian vote which translated into 5 constituencies (3 in Lau and 2 in Naitasiri). The SVT had the upper hand because of the wide gulf between urban and rural Fijians and the fact that rural Fijians were allocated more seats. The military and significant members of the Methodist Church bloc-voted for the SVT boosting its overall win. Kamikamica’s announcement that he would form a Coalition with Indo-Fijians also robbed him of crucial Fijian votes. Kamikamica lost his own seat.

Ratu Mara had no choice but to ask Rabuka and the SVT to form the next government. Rabuka had the support of 37 MPs (31 SVT, 4 GVP, one independent and Rotuma’s Manueli). He did not have to rely on Indo-Fijian MPs. His main critics now nested in the rival FAP political bure. The indigenous Fijian political elite had embarked on an uncertain journey of political rivalry in the future.The only thing the 1994 election resolved was which Fijian was to become Prime Minister and the answer was Rabuka and not Kamikamica.

The irony is that Indo-Fijian political leaders had become power brokers in the face of Fijian disunity. The newly-elected Prime Minister Rabuka could not ignore their demands for constitutional change in the light of political and ‘kama sutra’ scandals hovering over his head. But he could find refuge in the constitutional process, and he was forced to initiate negotiations between Reddy and Chaudhry culminating in the setting up of the Constitutional Review Commission (The Reeves Commission).

The recommendations of the Commission provided the basis on which the Joint Parliamentary Select Committee (JPSC) made its recommendations to Parliament. The end result, as we know, was the new electoral system, accountability, and multi-party government concept in the 1997 Constitution of Fiji

To be continued

and Slarms i-Taukeis

It is no secret that disgruntled Fijian politicians under the guise of Taukeism played a leading role which set the stage for George Speight and his henchmen to overthrow the Chaudhry government. Land and race was mixed with politics, even though these sensitive issues were not on the voters minds.

A Tebbutt Research on behalf the Fiji Times in April 1999 revealed that 26% of the voters thought unemployment was the most important issue in the election (Fijians 30% and Indo-Fijians 23%); followed by land issues/ALTA (14% -Fijians 8% and Indo-Fijians 21%).

According to SVT official Jone Dakuvula, a SVT-inspired agitation and destabilisation against Chaudhry began almost immediately after Chaudhry’s win. Jim Ah Koy, who was Finance Minister in Sitiveni Rabuka’s last government, while distancing himself from Speight’s take-over of Parliament, said he understood the Speight’s groups frustration and anger. He blamed the Chaudhry government’s ‘arrogance and obduracy in not listening to the sensitivities of the indigenous Fijians’.

Chaudhry sought to introduce a Land Use Commission to restructure land ownership

On 3 April 2000, based on World Bank Report and other reputable sources, Chaudhry declared Fiji would remain poor as long as the land remained underdeveloped. That ‘development’ required larger plantations and more secure titles in order to attract investment. Chaudhry also offered small Indo-Fijian growers $28,000 each to leave their farms and proposed that leases be extended for 60 years at the current low rents. Both the Council of Chiefs and the NLTB opposed these measures, accusing Chaudhry of favouring the Indo-Fijian tenant farmers and undermining the Council of Chiefs. Ironically, as the plight of the Indo-Fijian farmers worsens, with frightening consequences for the econony in general, the Interim Administration has agreed to pay the displaced farmers $28,000 or less depending on their circumstances.

On the day of Speight’s coups, about 5,000 people marched through Suva, demanding Chaudhry’s removal, following a similar march on 28 April. Marchers denounced the Government’s planned changes to land use, accusing it of moving to ‘usurp land’ from native landowners. They also attacked Chaudhry for showing ‘disrespect’ for the Council of Chiefs. The marches were called by the Fijian chauvinist Taukei Movement and led by Apisai Tora, who lost his parliamentary seat in the general elections. Tora revived the Taukei, which also staged marches and carried out racial attacks on Indo-Fijian citizens and politicians as a prelude to the 1987 coups. SVT secretary Jone Banuve gave his endorsement to Speight as he entered the besieged Parliament to meet him. He also issued a statement in the SVT’s name, saying: ‘We will never accept the reinstatement of the Chaudhry, nor any non-Taukei leadership’.

The SVT’s parliamentary leader, Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, said he knew nothing about the statement.Whether or not Kubuabola, the principal architect of the 1987 coups, knew of the statement, most of the Fijian politicians and leaders were attempting to leverage favourable outcome. While Sitiveni Rabuka issued a statement saying there should be ‘no amnesty’ for Speight and his followers, his ambiguous position was summed up in comments to the media: ‘I sympathise with your [Speight’s] cause, but I don’t agree with your methods.’ Tora, like Rabuka, said he sympathised with the cause but did not approve ofthe methods. He said the Taukei Movement had its own plan which he says was a much more logical approach. Chaudhry, on the other hand, had impressed and charmed even some of the die-hard Taukei members with his leadership qualities. Taukei activist Sivoki Mateinaniu said members of the Taukei Movement and Fijian politicians should learn from Chaudhry. ‘Mr Chaudhry’s policies are simple. He is just trying to implement what he promised; unlike the SVT government who forgot its election promises as soon as they were elected. Now the Fijians are still confused because our so-called leaders forgot to protect us in the [1997] Constitution. They did not even formulate legislation to protect our cause’, Mateinaniu said. ‘In the 1999 elections, they could not promise the Fijians anymore because they had failed to deliver in 1992 and 1994’. He called on Fijians not to listen to the hollow calls to disrupt stability and good governance. ‘The Taukei Movement now supports Mahendra Chaudhry’.

Chaudhry: Emperor Without the Prime Ministerial Robe

It was a remarkable transformation on Mateinaniu’s part and an honest and accurate assessment of Chaudhry’s leadership qualities. As the veteran politician and political commentator Sir Vijay Singh observed that, ‘Of all the major political parties, Mahendra Pal Chaudhry alone retained a clear vision of his party’s constituency-workers and farmers, the poor, and the deprived’ of all the races in Fiji’. Furthermore, the FLP had an extensive network to communicate that message. The Fiji Public Service Association, of which Chaudhry was the head, reached out to the public sector. He was also able to galvanise the farming community through the National Farmers Union, of which he was the head. The Labour candidate, Pratap Chand, as head of the Fiji Teachers Union, was able to reach out to primary and secondary teachers who play an educative role in our muti-racial community.

Sir Vijay R Singh: 'In restoring the democratic constitution, Rabuka did the Indians No Favour'

For many Indo-Fijian voters, the NFP’s, and in particular its leader, Jai Ram Reddy’s, achievements on the promulgation of the 1997 Constitution and talk of racial harmony were abstract issues. Also, the coalition with Rabuka’s SVT was insignificant. As Sir Vijay put it, ‘In restoring the democratic constitution’, Rabuka ‘did the Indians no favour’. He ‘restored what he had stolen in the first place’. The FLP also promised policies and initiatives of its own: the removal of the 10% Value Added Tax (VAT) and Customs Duty from basic food and educational items, review taxation on savings and raise allowances for dependants, provide social security for the aged and destitute, and lower interest rates on housing loans.The FLP had caught the peoples imagination. It was ‘Time for a Change’. And it was indeed a refreshing political change of scene.

The voters of Fiji elected by a landslide the ‘People's Coalition’ consisting of the FLP, the Party of National Unity (PANU) and the Fijian Association Party (FAP), with Labour winning 37 of the 71 seats, enough to govern on its own. However, it was the beginning of the end of Chaudhry’s government. The root and arguably the most significant cause of the demise of the Chaudhry government was not the Taukei Movement marches, the puppeteer George Speight and his financiers or Chauhdry’s arrogancebut (i) the provisions of 1997 Constitution of Fiji, and (ii) the non-Fiji Labour Party Fijian politicians in the ‘People's Coalition’. At the end of the day, these Fijian politicians had entered the government not on the platform of multi-racialism but as representatives of the various fractious Fijian political parties. They had racial and communal outlooks both in history and their pronouncements.

The Constitution and the election results had left the other half of the Fijians to brood, sulk, make political, provincial and tribal alliances, and plot or if necessary, to club their way back to political power under the guise of indigenous rights. Chaudhry had inherited a ‘Divided House of Representatives’ and as a result his antagonists were able to run through and occupy it illegally. He became a ‘Fall Guy’. Race and not tribalism triumphed on that fateful day, 19th of May 2000. The failed coup was executed to effectively oust his Fijian Association Party (FAP) and other Fijian guests from the House, who should not have been invited as his honoured guests in the first place under the 1997 Constitution. Chaudhry-the King Maker-had overnight become an Emperor Without the Prime Ministerial Dhoti (Indian sarong). The 1997 Constitution, with its provision for multiparty government, had made him both the victor and the vanquished.

His political gurus also slavishly allowed him to be dictated by Ratu Mara in the formation of his new government. As we have already pointed out, Chaudhry was caught with his Indian night political dhoti down in the company of ‘liu muri’ Fijian political bedfellows. Pre and post-cession Fijian history was repeating itself. The new Constitution had brought Fijian political quarrels to the Fiji Labour Party’s doorsteps. Chaudhry, the ‘misguided saint’, foolishly opened the political and multi-racial gate to his FLP-led government and in the process the ‘devils’ ignominiously and unceremoniously bundled him out of the political kingdom. ‘The King is Now Politically Dead but the Memory of Fijian Infighting Still Lives On’.

The Fijian Seeds of Chaudhry’s Troubles and Downfall

A general election was held over the period 23-30 May 1992, and one was held in February 1994. The new 1990 Constitution was overtly racist and biased in favour of Fijians. In the new 70 seat Parliament, Fijians were allocated 37 seats, Indo-Fijians 27, General Voters 5 and Rotumans 1. The Senate had 24 seats for Fijians, 9 for other races and 1 for Rotumans. In addition, all the key government posts-the presidency, prime ministership and heads of the judiciary, military, public service-had to be held by Fijians. A quota of at least 50 per cent Fijians was set for new recruitment into the public service. Another important feature of the distribution of Parliamentary seatswas the gerrymandering of the 37 Fijian constituencies because many urban Fijians had voted for Bavadra’s government in the 1987 elections. Thus rural Fijian voters were given 32 constituencies with the remaining 5 going to urban Fijian voters.The 1992 Elections With the new Constitution promulgated and Fijian political supremacy guaranteed, the first general election was held in 1992.

The principal parties that entered the election contest were: SVT, FLP, NFP, General Voters Party (GVP) and the Fijian Nationalist United Front (FNUF). Meanwhile, the NFP-FLP Coalition had split up following the death of Dr Timoci Bavadra. The FNUF, led by the late Sakiasi Butadroka, was a coalition of extremists from Fijian nationalist party (FNP) and SVT, which was formedin March 1991 with Rabuka as its political leader. The SVT had the backing of the Great Council of Chiefs. The SVT was not necessarily a unified political group and the real issue for the party was who was to become Prime Minister after the election: the ‘Father of the Coups’ Sitiveni Rabuka or the reliable, safe, moderate but right-wing Josevata Kamikamica? The political divisions within the Indo-Fijians, who are ‘All Chiefs and No Indians’, was not surprising. As the old coolie saying goes: ‘You put two Indians on a desert island and on your return next day to pick them up, you will find they have become three Indians.’ The FLP, led by Chaudhry, initially threatened to boycott the elections, stating that taking part would be tantamount to endorsing the 1990 ‘racist constitution’. However, at the last minute, the FLP leaders changed their stance and contested the election.

The result of the 37 Fijian seats were as follows: SVT 30, FNUF 5 and the last 2 went to Independents. The 27 Indo-Fijian seats were equally shared: the NFP won 14 and the FLP the other 13. The GVP won the 5 seats. The election results created the inevitability of a Coalition government. Although the SVT was theoretically in a position to form a coalition government, Rabuka was not assured of the coveted Prime Ministership. Some newly-elected SVT parliamentarians had thrown in their lot with Rabuka’s arch political rival, Josevata Kamikamica, a former Finance Minister in the pre-election Interim Government. Rabuka appeared to have 18 votes with Kamikamica only two, Filipe Bole four, and Ratu William Tonganivalu three. However Bole, Rabuka’s former teacher, freed his votes to allow them to support the majority-holder, in this case Rabuka who needed 36 confirmed votes from those who now held seats in the new House to grab the post of Prime Minister.

He went to the Government House asking President Ratu Penaia Ganilau to appoint him as Prime Minister, declaring that he had 42 votes. Ganilau asked Rabuka to demonstrate his support with accompanying signatures to confirm the numbers. Ganilau also was acutely aware that that another high-ranking chief, Ratu Mara, and a number of SVT personalities had been backing Kamikamica. In a cruel twist of irony, both the rival factions of the SVT began to court support from the NFP and FLP, the very parties deposed to ensure Fijian political supremacy in perpetuity. The SVT, formed to unify the Fijian people, could not agree on who should be its parliamentary leader. Rabuka was shocked to learn that Kamikamica had cut a deal with the veteran Indo-Fijian lawyer and politician Jai Ram Reddy and the NFP, and as a result Kamikamica had 30 votes to Rabuka’s 26. In desperation, the desperately power-hungry Rabuka, who had imprisoned Chaudhry twice, and had terrorised him and his family since 1987, shamelessly turned to the FLP leader for his political survival. But first Rabuka had to be humbled and humiliated, and reminded that power flows from the fountain of a ball point pen and not from the barrel of a Fiji Military Forces gun with a sticker reading, ‘God Loves You’.

Rabuka Scrambles to Form Government but Biltes Bullet and Begs for Chaudhry's Support

So Chaudhry and the FLP laid down the conditions for their support for Rabuka: a review of the Constitution; repeal of several controversial labour decrees, scrapping of the Value Added Tax (VAT) and land tenure reforms. The so-called Methodist preacher, a decorated solider, and a cynically pragmatic Fijian nationalist Rabuka, who desperately needed Chaudhry’s 13 historical votes, agreed to sign a letter committing himself to a deal with the FLP. The letter read: ‘I acknowledge the proposed outlined in your letter (2 June) delivered this morning. I have considered your proposals favourably and agree to take action on these issues, namely the constitution, VAT, labour decree reforms and land tenure on the basis suggested in your letter. I agree to hold discussions on the above issue in order to finalise the machinery to progress the matter further.’ In return, he got Chaudhry’s 13 votes to take him well in excess of his required 36 for the post of Prime Minister. The FLP however informed Rabuka that it would not be part of the governing coalition. Desperate to remain Prime Minister, Rabuka had accepted all the conditions in writing, only to dishonour them on resuming power. He had managed to secure thesupport of the GVP, the Rotuman representative Paul Manueli, his former army commander, and 2 independents.

A Deal with the Devil: Rabuka Betrays Agreement With Chaudhry

Now he had the numbers and the prime ministership in his sulu, Rabuka backed away from the agreement with the FLP. A spokesman of his insisted that all Rabuka had agreed to do was to discuss the issues that had been raised. There was, he stated, no agreement to do any more than this. As his official biographer John Sharpham recently put it, ‘Rabuka had already learned the art of political double speak (what we in Fiji call aage pichie or liu muri) and was prepared to walk a precarious path to stay in power’.

King Maker makes ‘Deal with the Devil’

What about Chaudhry who had done a deal with Rabuka and delivered him and a faction of the SVT the primeministership? When Chaudhry was asked if he had done ‘a deal with the devil?’ he responded: ‘No, there was no deal; the fact is we laid down conditions’. He also acknowledged the irony of the situation between the jailed and the jailor. ‘Oh, yes’, he responded when asked, ‘we hope we can enjoy that type of irony, which does not happen very often’.Chaudhry clearly relished the role of king-maker where an Indo-Fijian was called upon to arbitrate and settle question of leadership in the chiefly sponsored SVT.

It is surprising that the SVT had not run to the Great Council of Chiefs, whom they have recently elevated as the guardians of Fijian political aspirations, to settle the question of political leadership within their own ranks.. Meanwhile Kamikamica continued, in a typical Fijian fashion, to harbour his political ambitions against Rabuka. He refused to enter the post-1992 election Rabuka Cabinet, feeling that he would have been a better Prime Minister. Rabuka’s political woes however continued to shadow him in office, notably the ‘Stephen Affair’. Rabuka managed to ward off Chaudhry and his colleagues threatened withdrawal of Labour’s support for him by forming an inter-parliamentary committee to recommend appropriate machinery for considering changes to the 1990 Constitution.

In December 1992 he caused a stir in his own party and a surprise by proposing consideration of a government of national unity (GNU). According to Sharpham, ‘In March 1993 the government sent a paper on the concept to the Great Council of Chiefs, saying that the proposed government of national unity should be considered, but underplayed it as being of major importance. Mara, with other chiefs, questioned the need for such a government, and he led many chiefs who felt the idea had little merit. The chiefs decided to send it out to the provincial councils for their reaction, a move that was designed to quietly bury Rabuka’s proposal. This move was seen by some, to be aided and abetted, it has to be said, by some of the prime minister’s senior colleagues and advisors’. The SVT, and the Caucus complained at not having been consulted. Reddy half-heartedly wondered about numbers and representation. ‘We should have a figure’, he said, ‘that bears some resemblance to their [Indo-Fijian] numbers, contribution and work, and just not a token number’.

On the Indo-Fijian political front, the rivalry between the NFP and FLP intensified to the benefit of the NFP. In October 1993 the NFP candidates had roundly defeated their FLP Indo-Fijian candidatesin the municipal elections. The FLP had also fallen out with Rabuka in 1993 when he did not honour his promises in return for the FLP’s support for the premiership in 1992. On the Fijian political front, politics essentially still revolved around Rabuka and his political foe, Kamikamica. Rabuka’s critics seized the adverse aspects of the Report into the ‘Stephens Affair’ and called for his resignation. Rabuka brushed aside the resignation calls and even survived a motion of no-confidence in him. However, six Fijian MPs including Kamikamica, and David Pickering from the GVP, finally succeeded in their dogged pursuit to get rid of Rabuka when they voted with the Opposition against his budget 36-33 (with one abstention). The dissidents had hoped that Mara might either appoint Kamikamica or Ratu William Tonganivalu to form a new government. Instead, Rabuka exercised his constitutional right to dissolve his government and call for new elections.

The 1994 Elections and Fijian Divisions

It was the second general election under the new racist Constitution promulgated in 1990 after the two military take-overs in 1987 by Sitiveni Rabuka. The election was notable for the fact that the incumbent Prime Minister Rabuka was not expected to do well as dissidents in his party had broken away to form new political parties to challenge his rule. Fiji had undergone several changes prior to the 1994 elections. The President, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, had passed away, and the Great Council of Chiefs had elected Ratu Mara as his successor. The 1994 election campaign was dominated by intra-ethnic instead of inter-ethnic issues and conflicts and debates centred around communal issues because each group was fighting for communal seats. For the Indo-Fijians, the central issue of the racially biased constitution took a back seat to FLP/NFP rivalry, most of it at a personal level between Chaudhry and Reddy. Chaudhry and the FLP were repeatedly taunted by the NFP for their support for Rabuka in the aftermath of the 1992 election. The NFP claimed that the support had yielded nothing. The FLP, on the other hand, accused the NFP for being too close to Rabuka, who unwittingly reinforced this image when he announced that he planned to set up a government of national unity with Reddy after the elections.

FLP also attacked NFP for being an ‘Indian’ party as opposed to FLP’s multi.racial character. On the Fijian side, Kamikamica hastily launched a new political party, Fijian Association Party (FAP) to challenge Rabuka and the SVT. The FAP had the tacit support of the President Mara who had openly expressed his support for Kamikamica for the premiership at the Great Council of Chiefs but he was outvoted, in part by Rabuka’s politicised nominees on the Council. The SVT also condemned Kamikamica of helping to hand political power back to the Indo-Fijians. Kamikamica, on the other hand, played right into the hands of SVT nationalists when he made the strategic mistake of announcing that he would form a coalition government with the Indo-Fijians if he won the 1994 elections. He had promised to restore integrity and dignity to Fijian leadership.

Apisai Tora-Adi Kuini Join Fray

The already fragmented Fijian populace had the spectre of dealing with two other political entrants in the election-Apisai Tora and Adi Kuini Vuikaba-Speed, widow of the deposed premier Bavadra, and the remarried wife of the Australian political consultant Clive Speed. Tora, who has been a member of every political party in Fiji, this time formed his own All National Congress(ANC), which did not win a single seat in the 1992 election. He solicited votes on a platform of multi-racialism (yes!) and the exclusion of the Great Council of Chiefs from politics. At his political side was Adi Kuini. Earlier she had announced her retirement from active politics but she attempted a comeback as a candidate for the ANC. Another candidate for the ANC was David Pickering, who had defected from the GVP. At the end of the day the issue among the Fijians and Indo-Fijians revolved around leadership: did they want Rabuka over Kamikamica and Reddy over Chaudhry? The election results were interesting. The NFP won an extra 6 seats to increase its MPs to 20. There was also an increase of 5% of Indo-Fijian vote for it. The FLP only managed to win 7 seats. The results suggested that Indo-Fijians preferred Reddy’s cautious and moderate approach to Chaudhry’s often confrontational approach.

The Indo-Fijian voters were also not ready for Chaudhry’s politics of multi-racialism. Among the General Voters, the GVP managed to retain the four seats with the fifth going to Pickering. Tora and Adi Kuini were comprehensively beaten at the polls.The SVT and Rabuka managed to hold on to power by one seat, increasing their seats to 31.

In terms of voting percentages, SVT’s vote actually dropped 4%. The SVT’s Deputy Prime Minister, Filipe Bole, lost his seat to FAP’s candidate Ratu Finau Mara in the Lau constituency, where his father is the hereditary chief of Lau.The FAP only managed to win 14% of the Fijian vote which translated into 5 constituencies (3 in Lau and 2 in Naitasiri). The SVT had the upper hand because of the wide gulf between urban and rural Fijians and the fact that rural Fijians were allocated more seats. The military and significant members of the Methodist Church bloc-voted for the SVT boosting its overall win. Kamikamica’s announcement that he would form a Coalition with Indo-Fijians also robbed him of crucial Fijian votes. Kamikamica lost his own seat.

Ratu Mara had no choice but to ask Rabuka and the SVT to form the next government. Rabuka had the support of 37 MPs (31 SVT, 4 GVP, one independent and Rotuma’s Manueli). He did not have to rely on Indo-Fijian MPs. His main critics now nested in the rival FAP political bure. The indigenous Fijian political elite had embarked on an uncertain journey of political rivalry in the future.The only thing the 1994 election resolved was which Fijian was to become Prime Minister and the answer was Rabuka and not Kamikamica.

The irony is that Indo-Fijian political leaders had become power brokers in the face of Fijian disunity. The newly-elected Prime Minister Rabuka could not ignore their demands for constitutional change in the light of political and ‘kama sutra’ scandals hovering over his head. But he could find refuge in the constitutional process, and he was forced to initiate negotiations between Reddy and Chaudhry culminating in the setting up of the Constitutional Review Commission (The Reeves Commission).

The recommendations of the Commission provided the basis on which the Joint Parliamentary Select Committee (JPSC) made its recommendations to Parliament. The end result, as we know, was the new electoral system, accountability, and multi-party government concept in the 1997 Constitution of Fiji

To be continued