"Given Ratu Sukuna’s outstanding example of national leadership and public service, and the legacy of his fair-minded and equitable approach in the management of native land, it is such a great pity that public observance of Ratu Sukuna Day has been unilaterally discarded by the Bainimarama Government. The Government could have used Ratu Sukuna Day to promote national unity by drawing on our collective memory of him as a leader and statesman who was the first to recognize and accept that Fiji belongs to all its peoples both as individuals and as communities, and that our well-being and prosperity as a country require our commitment to each other, in mutual trust and cooperation, to building a shared future. It is not too late for Prime Minister Bainimarama to demonstrate that he is in charge of government as our elected leader. He can do this by restoring our collective observance and celebration of Ratu Sukuna Day, so that every generation of new leaders is reminded to learn from Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna’s outstanding example of selfless public service not for self-adulation or pecuniary gain but for the good of all." Jioji Kotobalavu

Sukuna statute

Sukuna statute BY

JIOJI KOTOBALAVU

AT THE FIJIAN TEACHERS’ ASSOCIATION HALL

SATURDAY, 23 APRIL 2016

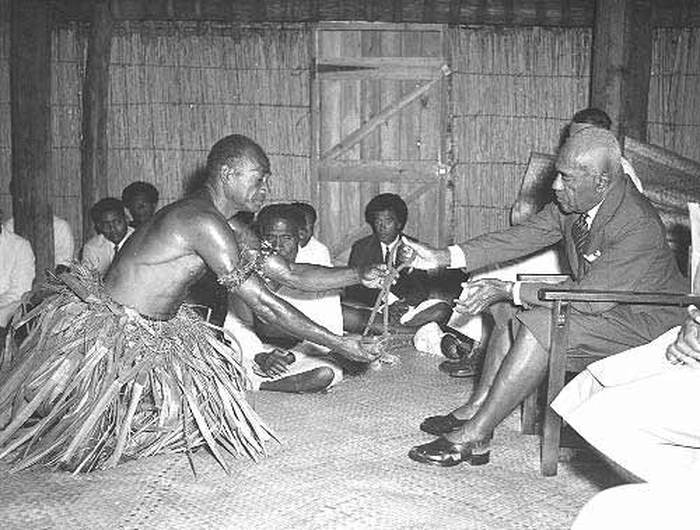

In the years following Fiji’s independence in 1970, the Alliance Government of Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara decided to proclaim a Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna Day to be observed as a public holiday. In addition, it commissioned a full-body sculpture of Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna to be prominently displayed in a public place. You will see this sculpture in front of Government Buildings opposite the Holiday Inn hotel. It is of Ratu Sukuna resplendent in formal morning suit with the Fijian sulu vakataga which he personally had designed. The Alliance Government also sponsored a biography of Ratu Sukuna, written by Dr Deryck Scarr. Ratu Mara’s Government did all these for Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna to serve a national purpose.

It was not only to honour him and to keep alive our collective memory and appreciation of him as a highly esteemed paramount chief and Fijian leader. But even more importantly, it was to enable us, the present generation, to reflect on his contribution as a national leader, through the native land policies he inaugurated under the Native Land Trust Ordinance. This ordinance or law was enacted by the Legislative Council in February 1940 with the full support and endorsement of the Great Council of Chiefs, acting on behalf of all Fijian customary land and resource owners.

Now, what was the purpose of this law? This Ordinance set out to establish a clear, streamlined and integrated administrative system for the management of native land. Control of all native land would henceforth be vested in a board of trustees, the Native Land Trust Board, presided over personally by the Governor, the resident head of the British colonial administration in Fiji. All native land is to be administered by the Board for the benefit of the native owners. The Board has power to set aside and proclaim native reserves, that is, areas of native land for the use of all iTaukei. These areas would be demarcated and kept for re-allocation in the event a Mataqali, for some reasons, needs land for its members. But the Board also has powers to grant to non-Fijians, under certain conditions, leases or licences over native lands not included in the native reserves. The native owners would benefit from the lease rent or licence fee income; the tenants would secure land for their farms, their houses, and their businesses; and Fiji as a whole would gain from the increased economic activities and the social security provided.

CHALLENGES FOR RATU SUKUNA

From our perspective today, it all appears to be very simple, logical and easy. The new integrated native land management system was to adopt a two-pronged approach. Ensuring the best interests of every Mataqali, including their land maintenance needs, would continue to be the first consideration. But surplus land or land not included in the demarcated reserves was to be availed under controlled leasing and licensing arrangements for use by others.

However, in order to fully comprehend and appreciate the magnitude of the challenges that Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna was confronted with as the senior-most adviser to the British colonial administration on native affairs, and as a paramount chief and the senior-most adviser to the Great Council of Chiefs, the highest representative council of all Fijians, we need to look into what was happening in Fiji at the time.

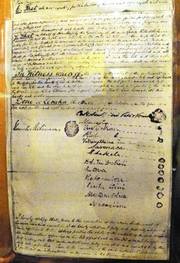

For this, we have to start with the Deed of Cession of 10th October, 1874. In that historical event, Ratu Seru Cakobau and other high chiefs ceded over to the British Crown, totally and unreservedly, the sovereignty over all lands and territories in Fiji. But in return, the British Crown, or Great Britain, reciprocated by giving the Fijian chiefs two assurances for which, even today, we should always be grateful. First, Fijian possession of their tribal lands according to their custom and usage would remain with them in accordance with the English common law principle of native or aboriginal title. Second, Britain expressly recognized the position and authority of the high chiefs over their people, to be exercised in accordance with the laws of the British colony.

Gordon

Gordon Sir Arthur Gordon’s priority was to establish the institutional structure and the enabling regulations for native administration and welfare of the Fijians, and to get the chiefs to agree on a common and standardized system of customary tenure for all native land.

With his encouragement, the Great Council of Chiefs met in Bua in December 1879. This was their fourth meeting to try and reach agreement on the land issue. They finally succeeded. This was their momentous agreement:

- That there shall be one custom for all native lands in Fiji,

- That the “true and real ownership” of all native lands would vest in the Mataqali alone,

- That it was neither possible nor lawful for any Mataqali to alienate their land,

- That all men shall be registered in their Mataqali together with their lands,

- That the register should be approved by tikina and provincial councils, and

- That the register shall be proof “for all time” as to the status and proof of the lands of each Mataqali in each province. (Peter France 1969, p. 113)

This was as a result of inter-tribal wars and through chiefly gifts and exchanges. However, what was causing great concern was the increased loss of native land through the uncontrolled and unregulated land buying activities of European traders and planters. It is recorded that many chiefs themselves were selling their communal land even without informing those of their tribes occupying the land. (Peter France 1969, p. 121) So, one can see that the challenge at the time was essentially to bring about uniformity and consistency in customary land tenure and to protect native land from the unscrupulous activities of land-hungry European planters and traders, and from the chiefs themselves from easily succumbing to underhand dealings by these newcomers to Fiji. The colonial administration itself had taken the first protective step by stopping all sales of native land and a Land Claims Commission was to be established to review all earlier land sales.

Now, we fast-forward in time to the 1930s to see the revolutionary changes in the social, economic and political situation that confronted and challenged Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna.

Firstly, there was a dramatic change in Fiji’s population dynamics.

In the population census of 1936, out of a total population of 198,379, the Fijians had declined to 97,651 or 49.2 per cent. In stark contrast, within 55 years the Indian population had substantially increased from the 588 or 0.5 per cent in 1881 to 85,003 or 42.8 (Fiji Bureau of Statistics 2012, p.3).

The second factor was that whilst the end of the indenture system and the arrival of free settlers from India were immediately followed by a quantum leap in need for land, the administrative system for the leasing out of native land at the time was extremely complicated and cumbersome. The potential lessor had to apply to the Commissioner of Lands in Suva or the nearest Commissioner of Division in the British colonial administration. The Commissioner would notify the Buli, who in turn consulted the Tikina Council at which the landowners expressed their views about the proposed lease. The Buli would then inform the Commissioner of the Tikina Council’s decision. The application and the recommendations would be considered jointly by the Commissioner for Lands and the Secretary of Native Affairs, and if they approved, the lease was then sold at a public auction to the highest bidder. One can imagine the many underhand dealings to influence the outcome of these land auctions (Brij Lal 1997, p. 46).

Patel

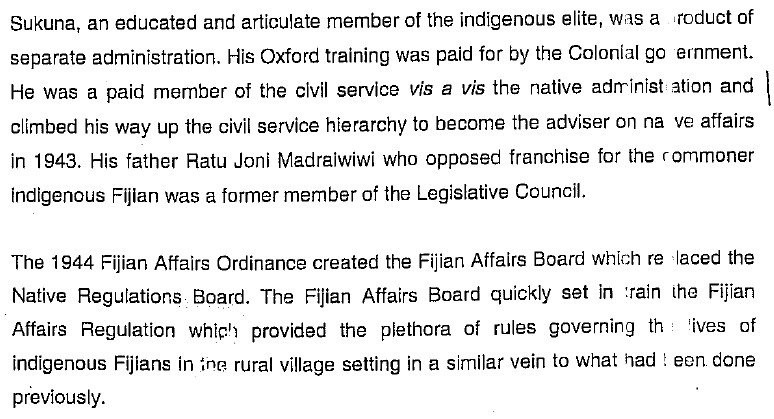

Patel In addition to their frustration with the lack of ready access to land, Indian leaders at the time, led among others by A D Patel, began from 1929 to agitate for increased Indian political representation in the Legislative Council. The Indian community had three seats in the Council, the Fijians five and the Europeans six. The Indian leaders also demanded the abolition of communal representation and its replacement by a common roll franchise system of one person one vote. (Brij Lal 197, pp.38-39) In addition, they continued their call on the British Government to honour what was promised in the “Lord Salisbury’s Despatch” of March 1875. The undertaking was reportedly that those who had completed their indenture were to be given rights and privileges as free settlers no less inferior to those of British subjects resident in the colony. (Brij Lal 1997, pp.5-6) Furthermore, as recorded by Dr Brij Lal, in 1935 the Government of India itself intervened and reminded the British colonial administration in Fiji that the colony’s well-being “must largely depend upon a satisfactory adjustment of [Indians’] rights and opportunities in relation to agricultural land” (Brij Lal 1997, p. 47).

So all these developments, the dramatic decline in Fijian population both in total number and as a percentage of the total population, the rapid increase in Indian population, the substantial increase in Indian community need for access to land, the incessant and increasingly vociferous demands by Indian political leaders for increased political representation in the colony’s Legislative Council, and external pressure from India, were bound to arouse Fijian fears about the security of their land and their future. Their fears and anxieties were politically and conveniently exploited and stoked by the minority community of local European settlers and business owners for their own security. This was led by the elected European members of the Legislative Council.

THE VISION AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF RATU SIR LALA SUKUNA

It was against this background and environment that Ratu Sukuna convened a meeting of the Great Council of Chiefs in 1936 and told the gathered chiefs:

“We cannot in these days adopt an attitude that will conflict with the welfare of those who like ourselves live peacefully and increase the wealth of the Colony. We are doing our part here and so are they. We want to live; they do the same. You should realize that money causes a close inter-relation of interests. If other communities are poor, we too remain poor. If they prosper, we also prosper. But if we obstruct other people without reason from using our lands, following the laggards there will be no prosperity. Strife will overtake us, and before we realize the position, we shall be faced with a situation beyond our control, and certainly not to our liking…You must remember that Fiji today is not what it used to be. We are not the sole inhabitants; there are now Indians and Europeans”. (Deryck Scarr 1983, p. 219)

Ratu Sukuna made this statement four years before his Native Land Trust Board Bill was presented in the Legislative Council. The proposed legislation, drafted in 1937, encapsulated his vision of what he thought would be the best arrangements for both the Fijians and for Fiji. And he allowed enough time in order to build up support for his new native land management policies among the chiefs and the Fijian community as a whole.

In reflecting on this, we can say that his greatness as a leader and statesman is that his vision as he articulated then remains true today as the foundation of public policy on native land. And further, his approach in assiduously taking meticulous care to consult the Great Council of Chiefs and to secure their support for his two-pronged management regime for native land, as contained in the Native Land Trust Ordinance, sets the example of what our government and political leaders today ought to be doing collectively and regularly with all iTaukei land and resource owners.

--firstly, the magnanimity and benevolent policy of Great Britain to the Fijians,

--secondly, the decisions taken by the Great Council of Chiefs at Bua in 1879 in setting a common policy framework for customary ownership by Fijians of their communal lands through the Mataqali, and

--thirdly, of Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna’s codified dual-tiered policy on the protection and use of native land,

that the iTaukei today still own as their customary possession, 91 per cent of all lands in Fiji.

And to all these, we must add this politically significant fact: that not only are the iTaukei the majority landowning community, they are also numerically today Fiji’s majority ethnic and cultural community with close to 60 per cent of our country’s total population. The 2007 population census showed that since the overall decline in their population numbers up to the beginning of the 1940s, the iTaukei have increased their numbers to 475,739 or 56.7 per cent of Fiji’s total population. And the census also gave a projection based on the iTaukei crude per capita birthrate, that the iTaukei population share will increase further to 68 per cent by 2030 (Fiji Bureau of Statistics 2012, p.3).

Based on these facts and projections, the iTaukei can feel confident about their future. But this is provided they are politically united in general elections to elect Fiji’s Parliament and national executive government, and provided further that they maintain effective control of political leadership in government. This places the iTaukei in the enviable position that out of close to 200 nation states in the international community, Fiji is one of only of two countries [the other being Bolivia] where the indigenous population makes up the majority ethnic and cultural community and still owns the vast proportion of the country’s lands.

Fijians should also appreciate that right from the commencement of British colonial administration of Fiji in 1874 Britain had recognized the practical utility of allowing Fijians through their chiefs and traditional councils to administer their own native affairs. Recognizing this right to indigenous self-determination was not common in British colonial policy. In the international community this right of self-determination of indigenous peoples was not recognized until the ILO Convention 169 of 1989 and the United Nations General Assembly 2007 Declaration on the Rights Indigenous peoples. The creation by Ratu Sukuna under the Native Land Trust Board Ordinance of the Native Land Trust Board to administer all native land for the benefit of native owners was based on maintaining this right of self-determination of Fijians.

Compare this unique and exceptional situation of the iTaukei to that of the Maoris in New Zealand. From the Maoris’ equivalent of the Fijians’ Deed of Cession, the Treaty of Waitangi with Britain in 1840, their overall number as New Zealand’s indigenous people has fallen to less than 15 per cent of their country’s total population, and they have been massively dispossessed of their tribal lands to the point where today their customary communal lands comprise less than 6 per cent of all lands in New Zealand. (United Nations Special Rapporteur report on NZ 2010)

OUTSTANDING VISIONARY LEADER AND STATESMAN

I believe that Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna’s greatness as a national leader stemmed from the fact that he was the first Fijian leader to acknowledge that public policy on native land administration could no longer ignore the sociological reality that Fiji had become a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society. For him, it was unequivocally clear that whilst the protection of Fijian ownership of their customary lands and ensuring the adequacy of land for their maintenance would always be the paramount consideration, it was also a national necessity to give fair and equitable consideration to the needs of the many thousands of non-iTaukei who are dependent on access to native land for the livelihood of their families.

In realizing this and deciding to do something positive about it for the common good, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna was demonstrating the qualities in national leadership so vitally necessary in a multi-ethnic society like ours where land is such a highly sensitive and politicized issue, where the bulk of the land is owned by one community, where the majority of commercial users of the land are from the other communities, and where the productive use of land is so crucially important to the wellbeing of our entire country. He was demonstrating national leadership that is focused and dedicated to serving the best interests of all individual citizens and communities.

This is what is called visionary leadership. It is visionary leadership in the sense that Ratu Sukuna had a clear understanding of what the challenge is. This is the first essential component of good visionary leadership. The second element is that the person in leadership has a very good grasp and appreciation of the range of policy options that one may draw upon to deal with the challenge. This requires qualities of broad-and-fair-mindedness, of objectivity, of realism and pragmatism, and of placing the interests of others first and foremost and not your own self-interests.

But there is a third component element of visionary leadership which is rare and exceptional and which very few people in leadership positions possess. Jesus Christ in his human capacity is the first example that always comes to mind as the foremost of these exceptional few. He sets the example in his own life of what he wants each of us to do with our own life. We believe in what he says, and so we follow, trying the best we can to attain the standard of sinless life he has set for us.

I fervently believe that what really sets Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna apart and makes him a truly visionary leader and statesman was that he possessed this third exceptional component element. And this is the ability to be humble and to realize that you may have a clear understanding of the challenges before you, and you may have a very clear appreciation of the best solution in light of the facts in issue and the circumstances of the particular challenge before you, but if you are unable to persuade and to convince the stakeholders to willingly and wholeheartedly follow you, you simply cannot be a successful leader. People are human beings and as such there is an in-born and primordial instinct in each one of us that tells us to resist being told what to do, if it is against our free will. This is the natural law foundation of our universal human rights as individual persons.

Now, in what ways did Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna demonstrate that he had this third exceptional quality of visionary and statesman-like leadership?

When you read Dr Deryck Scarr’s biography of Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna (Deryck Scarr 1980), you cannot help but be moved that here was a paramount chief at the very top of the chiefly hierarchy, and yet he had the clarity of mind and the humility to realize that in order to succeed with the solution to the challenges confronting our country, he could not act alone. In the exigencies of the situation, and as Secretary for Native Affairs, he had the option of simply advising the Governor, the head of the British colonial administration and chair of the Legislative Council, to table and to promulgate the Native Land Trust Board Bill. Instead, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna advised the colonial administration that here in Fiji on anything to do with native land the imperative for government is always to first consult the indigenous owners through their own institutions or councils of collective consultations and secure their support. The rationale for this is very simple. In order to succeed with a policy initiative on native land you need to carry with you the willing and voluntary support of the land and resource owners. This requires national leadership that believes firstly, in conducting full, open and good faith consultations with the land and resource owners, and secondly, in ensuring their consensus support.

Consensus support does not mean simple majority support as in our Parliament, which has led cynics to say that what we have in Fiji today is a constitutionally and democratically mandated system of elected tyrannical government. Nor does consensus support mean the 60 per cent numerical endorsement yardstick used by the current Government under its Land Use Decree to give itself the mandate to grant leases on Mataqali land with a duration which could be as long as 99 years. Consensus agreement approach as exemplified by Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna and which is practised in all traditional councils, including the Great Council of Chiefs, requires that every representative voice, as reasonably as is possible, must be heard and a final decision is taken only when all delegations present have been consulted and their voluntary support obtained. This is decision-making in accordance with the Fijians’ customary way and the natural justice principle of procedural fairness. So through the patient and sensible approach he took in building up collective consensus support for his land policy initiative by consulting the Great Council of Chiefs and ensuring that he had its support, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna epitomizes that style and quality of national leadership that is truly visionary and statesman-like.

OUTSTANDING PUBLIC SERVICE

And what is further remarkable about him is that he dedicated his entire life to public service. There is never any record or whisper that he took advantage of his commanding authority in the Colonial Service or his high chiefly position in society to enrich himself or his family with physical or financial assets. This is not surprising because when I joined the Public Service in 1968, it was still the British Colonial Service and it maintained very strict and rigorous standards of professional probity and integrity.

Because of his high chiefly stature and official standing and reputation, Fijians from all parts of Fiji held Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna with a combination of awe, admiration and reverent fear. Whenever he approached, or passed by, people would show their traditional respect in the customary way by sitting on the ground with their heads bowed and hands clasped. One does not see this today. Dr Scarr, his biographer, records that Ratu Sukuna’s long-time work for the Native Lands Commission took him to all parts of Fiji and made him “among Fijians the best known Fijian and most respected man in the country”. (Deryck Scarr 1980, p.60) I personally remember the elders of Navala Village in the interior of Ba Province telling of Ratu Sukuna’s occasional visits and camping in isolation “to consult with the Spirits”. They venerated him. Such was his powerful mystical impact on the imagination of ordinary Fijians.

Those who were close to Ratu Sukuna by family ties, fondly and affectionately remember that one of his noble and endearing qualities was that he kept an open house for young chiefs from other chiefly families. He had a keen interest in their upbringing and preparation for future leadership. He was a traditionalist and believed in chiefly leadership as the way to hold the Fijians together. His sponsorship of Ratu Mara’s and Ratu Dovi’s education overseas was a manifestation of this. He also maintained a particular interest in solidifying kinship ties among the chiefly families and made use of the distribution of land allotments for that purpose. But whatever he did, it was always for a bigger Fijian community-related purpose and not for his own personal gain. (Adi Finau Tabakaucoro, personal interview, 15th April, 2016)

So, the legacy that Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna has left for us to remember him on is essentially about his exemplary leadership and his life-long commitment to public service. He did not enrich himself with personal possessions and wealth. All he has left behind are the enduring results of his sterling services to the people of Fiji. On this account alone, he stands miles above those who succeeded him, including those in prominent leadership positions today.

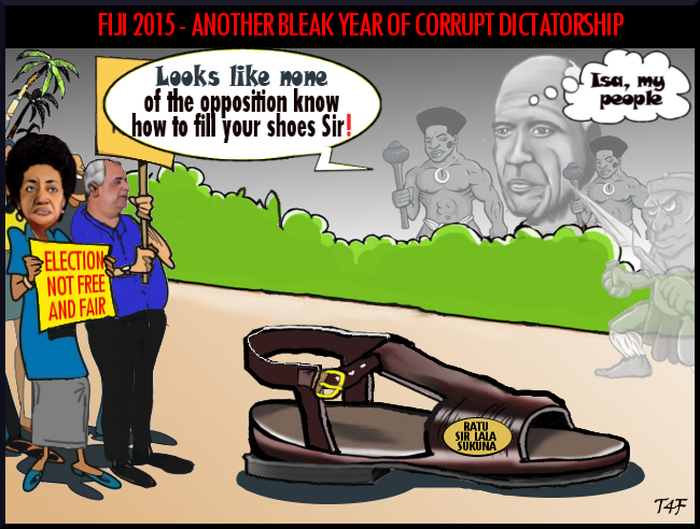

A CALL TO THE GOVERNMENT

Given Ratu Sukuna’s outstanding example of national leadership and public service, and the legacy of his fair-minded and equitable approach in the management of native land, it is such a great pity that public observance of Ratu Sukuna Day has been unilaterally discarded by the Bainimarama Government.

The Government could have used Ratu Sukuna Day to promote national unity by drawing on our collective memory of him as a leader and statesman who was the first to recognize and accept that Fiji belongs to all its peoples both as individuals and as communities, and that our well-being and prosperity as a country require our commitment to each other, in mutual trust and cooperation, to building a shared future.

It is not too late for Prime Minister Bainimarama to demonstrate that he is in charge of government as our elected leader. He can do this by restoring our collective observance and celebration of Ratu Sukuna Day, so that every generation of new leaders is reminded to learn from Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna’s outstanding example of selfless public service not for self-adulation or pecuniary gain but for the good of all.

And by the way, for all that Great Britain has done to ensure that the iTaukei still own, as their customary possession, 91 per cent of all lands in Fiji, and if the Fiji Military Forces is to continue to proudly wear their crimson and white official and ceremonial uniform, the Prime Minister can also decide that Fiji is to retain its current Independence Day flag.