"When I left Fiji in 2008 (with the generous assistance of the military), I was far from alone in thinking he couldn’t last five years, never mind ten. Surely the people of Fiji would not put up with him? He has proved us all wrong. The patience of “the people” has turned to be all but endless and the next intake of first-time voters will not know of Fiji under democratic rule...And now with Bainimarama’s “clean up” campaign all but complete corruption – claimed as a trigger for his coup – is endemic. Decisions are made, deals are done, and fortunes are made - all behind closed doors. And Fiji sucks in the snake oil salesmen as never before. Nevertheless the reality is that while the seething resentment hasn’t gone away, neither has Frank.

Age alone can stop Frank now."

Hunter

Hunter By RUSSELL HUNTER

Former Publisher/CEO

Fiji Sun

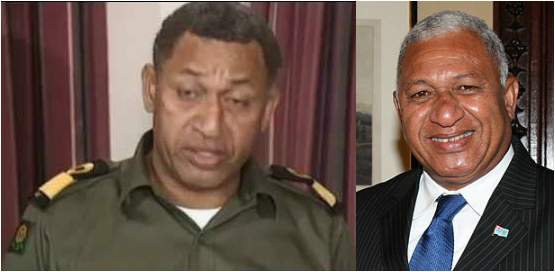

“I never wanted this job,” Fiji’s dictator Frank Bainimarama told an Australian journalist a month after his “clean-up” coup of 5 December 2006.

Unlike so many of his public statements of the time it may not have been an outright lie.

For while he had been determined to retain his military job and thus keep secret his true and shameful role in the coup that removed the elected government of Mahendra Chaudhry in 2000 and his subsequent alleged association with the murders of six Counter-Revolutionary Warfare unit soldiers later that year; he may not have originally imagined that he’d have to remove the government in order to do it.

But the seeds were sown three years earlier when the government of Laisenia Qarase (which Bainimarama was partly responsible for putting in place) decided not to renew his contract as commander of the armed forces. Bainimarama felt owed. After all, he’d betrayed his own people and narrowly escaped their attempt to murder him in retaliation in order to, as her saw it, create this government that was now turning against him.

When his senior officers refused to support him in a coup aimed to keep his job the road must have become clearer for Voreqe Bainimarama.

After another attempt failed – again because he lacked support among senior staff – Bainimarama weeded out opposition in his own ranks and even campaigned against the government in the election of 2006. He was rejected again, this time by the electorate, and it stung.

Qarase’s team won a convincing victory in May 2006 and was guaranteed by a solid parliamentary majority, to serve another term. It was poison to Bainimarama who knew his position was far from secure.

By November of that year the police were awaiting an opportunity to arrest him on charges of sedition. Seeking to avoid a bloody confrontation between themselves and Bainimarama’s 16-strong and heavily armed security detail, they bided their time. Bainimarama knew it and knew he had to act if he was to avoid spending the rest of his life in jail.

Ten years ago on 5 December 2006 he took over the government of Fiji in an act of treason.

Politicians tell lies. They make promises they know they have no intention of keeping. They see such things as necessary evils among the means to achieve and retain power in the hope that, once elected, they will be able to govern for the greater good as they see it.

But Bainimarama was no politician (though he has learned much of that dark art in 10 years). He was a military man for whom the mission justified all and any means to fulfil it. And his mission now was to appoint himself leader of his country and to run it his way for his good.

But why the lies? Why when he had all the guns, all the troops, all the aces in the pack did he feel the need to lie to his people, presumably to win their support? And in his “inaugural address” with a straight face, he told some whoppers. These are too many to detail here but “no member of the RFMF will benefit from this coup” and “fresh elections in six months” give the flavour of his speech.

But, again, why the need to utter such brazen untruths? It’s likely that he felt insecure, that in those early days his position was precarious. Certainly there was much Dutch courage being taken at the officers’ mess at that time when as one former senior officer put it to me “They’re shit scared of a public uprising”.

And while it may explain his need to placate public opinion on Day One, that fear has never left him (though he did in an unguarded moment proclaim that he had no need to pay attention to public opinion). There’s no crime without guilt.

So what sort of man was Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama at that time a decade ago? Former police commissioner Andrew Hughes (whose disgraceful and disgusting treatment at the hands of his then military counterpart has been well-documented here and elsewhere) recalls him as affable but not without inner demons. Hughes, like most senior police officers a keen observer of humanity, remembers a good sense of humour but a certain fragility. Their meetings would always take place at Bainimarama’s office (“I always had to go to him”) while Hughes became convinced his counterpart was suffering from Post Trauma Stress Disorder. “After all, they tried to kill him”.

Some former officers are less generous. Some say he was and is an outright coward (presumably because of his abandonment of his men under fire) while more considered respondents regard him as man without moral compass, a narcissist who subordinates everything and anything to his own wants.

Whatever the truth, he was to command Fiji for ten years. He still does.

After a few false starts – most notably the People’s Charter (whatever happened to that?), Fiji began to understand just what Bainimarama meant when he spoke repeatedly of his vision for “true democracy”. It’s clear now that what he meant was the people’s freedom to do as he ordered.

In echoes of dictatorships throughout history the “people” would be invoked at every turn in an effort to promote the fiction of a popular base.

Thus the People’s Charter was foisted on the “people” whether or not they wanted – or cared about – it. Similarly the much-touted People’s Constitution that appeared to replace it finally emerged as two people’s constitution after it became clear that the “people” had no stomach for what Bainimarama wanted and the document that did reflect the wishes of the “people” was burned.

But before any of that could happen, Bainimarama needed to get his hands on all the controls and remove all obstacles. Thus the Great Council of Chiefs had to go, the Methodist Church had to be neutralised. The media (as we shall see), the justice system, the banking system, the civil service, the police, the prisons system and even the monopoly pension fund would all have to bend to the will of one man. Or else.

Bainimarama’s right hand in all of this and more has been Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum, the former bank lawyer whose vaulting ambition has brought him close to the pinnacle of power. It’s almost certainly misguided but many ethnic Fijians are convinced – very possibly for base racist reasons – that Frank is merely the glove puppet with Khaiyum’s hand at its heart. It’s an untrue image but there can be little doubt that it exists in popular myth.

But the indefatigable Attorney General and minister for much else has delivered a conveyor belt of decrees, Acts and rules all aimed squarely at making his boss’s power absolute behind a thin veil of fictional legality. George Orwell, the author of Animal Farm and 1984, would have instantly recognised Bainimarama’s Fiji – a land in which the law is precisely what he says it is on any given day, a land in which there is no dissent allowed, where “Big Brother” is constantly on watch for behaviour and thoughts that venture beyond the frontiers of the norm.

An early target was the media. After deportations, threats, promises and clumsy attempts at subtlety failed to deliver the desired result – which was and is total control – Khaiyum brought forth his media decree that, in effect, gives the regime absolute power over all forms of domestic mass communication.

It was to be a temporary measure but the promise was akin to that of a 2007 election.

The Fiji media has in some cases sold all pretence of integrity for exclusive government advertising aimed as much at harming competitors as advancing itself. The national broadcaster is regime owned and controlled. Fiji TV has had to be brought into line at considerable cost to its shareholders. Other broadcasters are more than ever focused on mindless music rather than any attempt at impartial news or analysis.

The regime-hated Fiji Times continues to provide the occasional ray of light – at great risk to its continued existence as has been demonstrated by the blatant double standards applied under what passes for the law. Journalists and editors who seek to tell the truth about this regime face the direst of consequences.

The media – with the possible exception of The Fiji Times – is not trusted.

But there has been a price. Few if any print media customers are willing to pay for propaganda and that has led to a circulation crisis. Meanwhile, people follow TV and radio for entertainment only while the regime-appointed and controlled media policeman has no public credibility.

But the stirrings of discontent have not gone away and as the realisation dawns that Bainimarama won’t be around in another 10 years they are not likely to. Indeed Sitiveni Rabuka (who has made it no secret that he has his own demons to deal with) has told Fijileaks that SODELPA would restore media freedom to pre-2006 levels if elected to restore democracy to Fiji. NFP leader Biman Prasad is similarly a well known believer in freedom of expression and media.

But what of those many journalists and editors who have openly embraced the Bainimarama way? When - not if – full freedom is restored, will they be able to swap uniforms and become independent practitioners? Only time will tell.

Meanwhile, the hunger for independent news and analysis has not been sated by the regime’s media as evidenced by the exploding popularity of sites such as this and the criminal targeting of it by individuals who so far have enjoyed the regime’s protection.

More than a few lawyers – insisting on anonymity for obvious reasons – have told Fijileaks that they seek wherever possible to guide their clients away from the court system for fear that they will not receive an impartial hearing. Indeed the courts as well as the media are often cited as among the main casualties of the Bainimarama coup.

Judges and magistrates can be and have been appointed or dismissed at the whim of the regime. There are recorded instances of magistrates being removed for delivering the “wrong” verdicts. Prosecutions sometimes were and are selective with the selection criteria having little to do with the alleged offences.

Bainimarama has openly stated that he will stand by “my men” (it seems his team is gender specific) regardless of what they may have done in the line of duty.

The conviction, then, of those who tortured and caused the death of Vilikesa Soko is being seen as a breakthrough for justice (see Fijileaks extensive coverage). And one hopes it will be but, on past experience, we need first to see whether those convicted will serve their sentences.

Indeed Fijileaks has offered coverage of the many and serious anomalies and double standards in the justice system that the heavily censored onshore media are quite unable to provide, much as a few of them might like to.

The decisions by a range of people to serve this unjustified system of “justice” is a matter between themselves and their consciences but certainly those decisions have done nothing to uphold the rule of law or generate respect for it.

There’s one law in Fiji. Frank’s law.

Similarly the political and electoral systems have one united ultimate aim: to keep Frank and his cronies in power for as long as they choose to be there.

The fact that there has been found to be a need for a minister for elections sums it up. And that fact that the minister is a high official of the ruling party adds emphasis.

It’s all part of the transparency and accountability pledged by Bainimarama back in 2006 in his infamous “clean up” speech.

Of course all incoming regimes – legal and illegal - piously pledge to implement these twin pillars of representative government. None deliver.

But Bainimarama’s non-delivery has been nothing short of spectacular. Fiji has become a closed society under his rule with the true state of the nation’s affairs known only to an elite few. All checks and balances have been eliminated to the extent that the Budget itself needn’t – and doesn’t – prevent the regime from spending and cutting where when and how it sees fit without reference to any properly elected body.

For the detailed budget papers once combed by journalists, economists and commentators of all political hues are no longer provided. They only led to questions, after all.

And now with Bainimarama’s “clean up” campaign all but complete corruption – claimed as a trigger for his coup – is endemic. Decisions are made, deals are done and fortunes are made - all behind closed doors. And Fiji sucks in the snake oil salesmen as never before.

Nevertheless the reality is that while the seething resentment hasn’t gone away, neither has Frank.

When I left Fiji in 2008 (with the generous assistance of the military), I was far from alone in thinking he couldn’t last five years never mind ten. Surely the people of Fiji would not put up with him?

He has proved us all wrong. The patience of “the people” has turned to be all but endless and the next intake of first-time voters will not know of Fiji under democratic rule.

Age alone can stop Frank now.

Former Publisher/CEO

Fiji Sun

“I never wanted this job,” Fiji’s dictator Frank Bainimarama told an Australian journalist a month after his “clean-up” coup of 5 December 2006.

Unlike so many of his public statements of the time it may not have been an outright lie.

For while he had been determined to retain his military job and thus keep secret his true and shameful role in the coup that removed the elected government of Mahendra Chaudhry in 2000 and his subsequent alleged association with the murders of six Counter-Revolutionary Warfare unit soldiers later that year; he may not have originally imagined that he’d have to remove the government in order to do it.

But the seeds were sown three years earlier when the government of Laisenia Qarase (which Bainimarama was partly responsible for putting in place) decided not to renew his contract as commander of the armed forces. Bainimarama felt owed. After all, he’d betrayed his own people and narrowly escaped their attempt to murder him in retaliation in order to, as her saw it, create this government that was now turning against him.

When his senior officers refused to support him in a coup aimed to keep his job the road must have become clearer for Voreqe Bainimarama.

After another attempt failed – again because he lacked support among senior staff – Bainimarama weeded out opposition in his own ranks and even campaigned against the government in the election of 2006. He was rejected again, this time by the electorate, and it stung.

Qarase’s team won a convincing victory in May 2006 and was guaranteed by a solid parliamentary majority, to serve another term. It was poison to Bainimarama who knew his position was far from secure.

By November of that year the police were awaiting an opportunity to arrest him on charges of sedition. Seeking to avoid a bloody confrontation between themselves and Bainimarama’s 16-strong and heavily armed security detail, they bided their time. Bainimarama knew it and knew he had to act if he was to avoid spending the rest of his life in jail.

Ten years ago on 5 December 2006 he took over the government of Fiji in an act of treason.

Politicians tell lies. They make promises they know they have no intention of keeping. They see such things as necessary evils among the means to achieve and retain power in the hope that, once elected, they will be able to govern for the greater good as they see it.

But Bainimarama was no politician (though he has learned much of that dark art in 10 years). He was a military man for whom the mission justified all and any means to fulfil it. And his mission now was to appoint himself leader of his country and to run it his way for his good.

But why the lies? Why when he had all the guns, all the troops, all the aces in the pack did he feel the need to lie to his people, presumably to win their support? And in his “inaugural address” with a straight face, he told some whoppers. These are too many to detail here but “no member of the RFMF will benefit from this coup” and “fresh elections in six months” give the flavour of his speech.

But, again, why the need to utter such brazen untruths? It’s likely that he felt insecure, that in those early days his position was precarious. Certainly there was much Dutch courage being taken at the officers’ mess at that time when as one former senior officer put it to me “They’re shit scared of a public uprising”.

And while it may explain his need to placate public opinion on Day One, that fear has never left him (though he did in an unguarded moment proclaim that he had no need to pay attention to public opinion). There’s no crime without guilt.

So what sort of man was Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama at that time a decade ago? Former police commissioner Andrew Hughes (whose disgraceful and disgusting treatment at the hands of his then military counterpart has been well-documented here and elsewhere) recalls him as affable but not without inner demons. Hughes, like most senior police officers a keen observer of humanity, remembers a good sense of humour but a certain fragility. Their meetings would always take place at Bainimarama’s office (“I always had to go to him”) while Hughes became convinced his counterpart was suffering from Post Trauma Stress Disorder. “After all, they tried to kill him”.

Some former officers are less generous. Some say he was and is an outright coward (presumably because of his abandonment of his men under fire) while more considered respondents regard him as man without moral compass, a narcissist who subordinates everything and anything to his own wants.

Whatever the truth, he was to command Fiji for ten years. He still does.

After a few false starts – most notably the People’s Charter (whatever happened to that?), Fiji began to understand just what Bainimarama meant when he spoke repeatedly of his vision for “true democracy”. It’s clear now that what he meant was the people’s freedom to do as he ordered.

In echoes of dictatorships throughout history the “people” would be invoked at every turn in an effort to promote the fiction of a popular base.

Thus the People’s Charter was foisted on the “people” whether or not they wanted – or cared about – it. Similarly the much-touted People’s Constitution that appeared to replace it finally emerged as two people’s constitution after it became clear that the “people” had no stomach for what Bainimarama wanted and the document that did reflect the wishes of the “people” was burned.

But before any of that could happen, Bainimarama needed to get his hands on all the controls and remove all obstacles. Thus the Great Council of Chiefs had to go, the Methodist Church had to be neutralised. The media (as we shall see), the justice system, the banking system, the civil service, the police, the prisons system and even the monopoly pension fund would all have to bend to the will of one man. Or else.

Bainimarama’s right hand in all of this and more has been Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum, the former bank lawyer whose vaulting ambition has brought him close to the pinnacle of power. It’s almost certainly misguided but many ethnic Fijians are convinced – very possibly for base racist reasons – that Frank is merely the glove puppet with Khaiyum’s hand at its heart. It’s an untrue image but there can be little doubt that it exists in popular myth.

But the indefatigable Attorney General and minister for much else has delivered a conveyor belt of decrees, Acts and rules all aimed squarely at making his boss’s power absolute behind a thin veil of fictional legality. George Orwell, the author of Animal Farm and 1984, would have instantly recognised Bainimarama’s Fiji – a land in which the law is precisely what he says it is on any given day, a land in which there is no dissent allowed, where “Big Brother” is constantly on watch for behaviour and thoughts that venture beyond the frontiers of the norm.

An early target was the media. After deportations, threats, promises and clumsy attempts at subtlety failed to deliver the desired result – which was and is total control – Khaiyum brought forth his media decree that, in effect, gives the regime absolute power over all forms of domestic mass communication.

It was to be a temporary measure but the promise was akin to that of a 2007 election.

The Fiji media has in some cases sold all pretence of integrity for exclusive government advertising aimed as much at harming competitors as advancing itself. The national broadcaster is regime owned and controlled. Fiji TV has had to be brought into line at considerable cost to its shareholders. Other broadcasters are more than ever focused on mindless music rather than any attempt at impartial news or analysis.

The regime-hated Fiji Times continues to provide the occasional ray of light – at great risk to its continued existence as has been demonstrated by the blatant double standards applied under what passes for the law. Journalists and editors who seek to tell the truth about this regime face the direst of consequences.

The media – with the possible exception of The Fiji Times – is not trusted.

But there has been a price. Few if any print media customers are willing to pay for propaganda and that has led to a circulation crisis. Meanwhile, people follow TV and radio for entertainment only while the regime-appointed and controlled media policeman has no public credibility.

But the stirrings of discontent have not gone away and as the realisation dawns that Bainimarama won’t be around in another 10 years they are not likely to. Indeed Sitiveni Rabuka (who has made it no secret that he has his own demons to deal with) has told Fijileaks that SODELPA would restore media freedom to pre-2006 levels if elected to restore democracy to Fiji. NFP leader Biman Prasad is similarly a well known believer in freedom of expression and media.

But what of those many journalists and editors who have openly embraced the Bainimarama way? When - not if – full freedom is restored, will they be able to swap uniforms and become independent practitioners? Only time will tell.

Meanwhile, the hunger for independent news and analysis has not been sated by the regime’s media as evidenced by the exploding popularity of sites such as this and the criminal targeting of it by individuals who so far have enjoyed the regime’s protection.

More than a few lawyers – insisting on anonymity for obvious reasons – have told Fijileaks that they seek wherever possible to guide their clients away from the court system for fear that they will not receive an impartial hearing. Indeed the courts as well as the media are often cited as among the main casualties of the Bainimarama coup.

Judges and magistrates can be and have been appointed or dismissed at the whim of the regime. There are recorded instances of magistrates being removed for delivering the “wrong” verdicts. Prosecutions sometimes were and are selective with the selection criteria having little to do with the alleged offences.

Bainimarama has openly stated that he will stand by “my men” (it seems his team is gender specific) regardless of what they may have done in the line of duty.

The conviction, then, of those who tortured and caused the death of Vilikesa Soko is being seen as a breakthrough for justice (see Fijileaks extensive coverage). And one hopes it will be but, on past experience, we need first to see whether those convicted will serve their sentences.

Indeed Fijileaks has offered coverage of the many and serious anomalies and double standards in the justice system that the heavily censored onshore media are quite unable to provide, much as a few of them might like to.

The decisions by a range of people to serve this unjustified system of “justice” is a matter between themselves and their consciences but certainly those decisions have done nothing to uphold the rule of law or generate respect for it.

There’s one law in Fiji. Frank’s law.

Similarly the political and electoral systems have one united ultimate aim: to keep Frank and his cronies in power for as long as they choose to be there.

The fact that there has been found to be a need for a minister for elections sums it up. And that fact that the minister is a high official of the ruling party adds emphasis.

It’s all part of the transparency and accountability pledged by Bainimarama back in 2006 in his infamous “clean up” speech.

Of course all incoming regimes – legal and illegal - piously pledge to implement these twin pillars of representative government. None deliver.

But Bainimarama’s non-delivery has been nothing short of spectacular. Fiji has become a closed society under his rule with the true state of the nation’s affairs known only to an elite few. All checks and balances have been eliminated to the extent that the Budget itself needn’t – and doesn’t – prevent the regime from spending and cutting where when and how it sees fit without reference to any properly elected body.

For the detailed budget papers once combed by journalists, economists and commentators of all political hues are no longer provided. They only led to questions, after all.

And now with Bainimarama’s “clean up” campaign all but complete corruption – claimed as a trigger for his coup – is endemic. Decisions are made, deals are done and fortunes are made - all behind closed doors. And Fiji sucks in the snake oil salesmen as never before.

Nevertheless the reality is that while the seething resentment hasn’t gone away, neither has Frank.

When I left Fiji in 2008 (with the generous assistance of the military), I was far from alone in thinking he couldn’t last five years never mind ten. Surely the people of Fiji would not put up with him?

He has proved us all wrong. The patience of “the people” has turned to be all but endless and the next intake of first-time voters will not know of Fiji under democratic rule.

Age alone can stop Frank now.