"If I knew that this would have happened [Sawari snatched by Immigration officials on way to a 10.30 am meeting with the Director of Immigration in Suva] I would never have agreed to the meeting" -

Aman Ravindra Singh, lawyer for Sawari

His lawyer Aman Ravindra-Singh confirmed the pair was intercepted by Police at Korotogo in Sigatoka at 7.30am today while on their way to Suva for a scheduled meeting with Director of Immigration Nemani Vuniwaqa.

He said his client was transported in a Police vehicle to the Nadi International Airport and had boarded a flight bound for Papua New Guinea. Source: The Fiji Times, 3 February 2017

MAHENDRA CHAUDHRY'S CALL ANSWERED

And those who despicably and repeatedly branded SAWARI a

"MUSLIM TERRORIST" celebrating with glee; he was not even accorded NATURAL JUSTICE to explain himself to the Immigration authorities.

SAWARI NABBED AND DEPORTED:

ACCORDING to UN reports and even PNG courts, 90 per cent of refugees on Manus Island are ruled to have valid claims but they are not allowed to settle in the Australian mainland, instead being allowed to stay in

Nauru or Papua New Guinea

We mustn't forget that Laisenia Qarase was deposed and chased out of Suva and was forced to remain on MAVANA ISLAND, with the current Police Commissioner threatening to KILL Qarase if he returned to Suva. Like the Iranian asylum seeker Sawari, Qarase was branded a

security risk to Fiji

Fijileaks:

Coming soon: How Qarase escaped the violent pursuit by Bainimarama and his military thugs. And how those who helped Qarase flee to Mavana, themselves fled to Australia and sought political asylum in that country. Luckily, they did not end up on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea

Frank Bainimarama to Laisenia Qarase, 5 December 2006:

“___________ na cava tale dou se cakava tiko qori? Tukuna vua na luve ni magaitinana qori me sogota na gusuna de’u na lako yani i keri me’u yarataka na domona me vakavodoki i na waqa me fuck-off laivi i nodratou koro. Cava dou vinakata mo dou lai laulaumoku yani e keri? Dou veicai, sa oti na nomudou gauna. Tukuna vua na tamata qori me sogota na gusuna de’u na qai gole sobu yani me’u lai sogota vua”

It can be translated as follows: “_______________, what else are you people doing there? Tell that son of his mother’s vagina (referring to the then Prime Minister, Mr Laisenia Qarase) to shut his mouth or I’ll come down there and drag him by the neck so that he can fuck-off to his village. Do you people want to be beaten up? You people fuck each other, your time is over. Tell that person (again referring to Mr Qarase) to shut his mouth or I’ll come down to shut it for him.”

The Fiji Sun,

10 January 2008

In the days leading up to the 5 December 2006 coup the cat and mouse chase forced Laisenia Qarase, at the time the duly elected Prime Minister of Fiji, to finally flee to the safety of his home in Mavana in Vanuabalavu. He remained there and only returned to Suva to prepare for his court case against his deposers.

The question that the recent High Court judgment did not address, and I accept that it was not asked to consider, was whether the military, in confining Qarase to Mavana, was acting on the supposed and invisible “reserve powers” vested in the President, Ratu Josefa Iloilo.

And if the military was acting on the “reserve powers”, where did the military, through the President, get that power to confine the deposed Prime Minister in Mavana?

In a series of articles I will be arguing, based on the availability of new evidence as contained in the various court affidavits and other reliable sources, that the President’s constitutional powers ended the moment he allowed Commodore Frank Bainimarama to “step into his shoes” and all acts performed by the military afterwards in the President’s name, with or without his consent and blessing, has no basis in constitutional law.

In fact, the President did not have the reserve powers to perform the series of acts in the manner he did following the 2006 coup.

During the run up to the coup, I was under the impression that he was a neutral arbiter but evidence suggests to the contrary, especially his address to the nation: “In any case, given the circumstances I would have done exactly what the Commander of the RFMF Josaisa Voreqe Bainimarama did since it was necessary to do so at that time.”

As a result, I am departing from my own earlier arguments, which were previously based on skeleton evidence available to us.

Meanwhile, I disagree with the interim Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum’s warning to the media that he would not tolerate any contempt of court and comments on the recent judgment and anybody bringing the judiciary or the administration of justice into contempt will be called to account for their actions. I presume he knows better as a student of law that the conduct of the judges and their judgements are open to scrutiny once a judgement has been delivered by a court: In Attorney General v Butterworth [1963] 1 Q.B. 696 it was held that at common law, “a contempt of court is an act or omission calculated to interfere with the due administration of justice.” He must remember that the High Court has already delivered its verdict.

His constant threats to the media only re-enforce “the all-too-common tendency to view the attorney-general and his department as no more than the law firm that is always on call to serve the interest of the political party that is in power at the time”.

The A-G, despite his political role, and as supporter and adviser to the government, is meant to wear an apolitical hat in his parens patriae role as guardian of the public interest. The judiciary and the media are also guardians of the public interest.

In his fifth edition of Media Law (2008) Geoffrey Robertson QC, who successfully argued the Chandrika Prasad case before Justice Gates, writes on the issue of scandalising the court: “Scandalising the court was invented in the eighteenth century to punish radical critics of the establishment, such as John Wilkes [In the context of 18th century politics it was an attempt to protect Lord Mansfield from reasoned criticism of his oppressive judicial behaviour towards Wilkes and other critics of the Government].

Despite its apparent breadth, scandalising the court should not prevent criticism of the judiciary even when expressed in strong terms. “Justice is not a cloistered virtue” a senior Law Lord (Lord Atkin, Ambard v Att-Gen for Trinidad and Tobago, 1936), once said, and comment about the legal system in general or the handling of particular cases once they are over sometimes deserves to be trenchant… Scandalising the court is an anachronistic form of contempt.

Lord Diplock (Secretary of State for Defence v Guardian Newspapers Ltd (1985) has described it as “virtually obsolescent in the United Kingdom” and it has not been used here for 60 years.”

In their ruling in Qarase and Others v Bainimarama and Others, the three judges, acting Chief Justice Anthony Gates and Justices John Bryne and Davendra Pathik barely touched on Qarase’s enforced confinement on Mavava, but noted: “In his pleadings Mr Qarase stated, ‘The next morning the Prime Minister escaped from Suva’. The defendants claim he left Suva that day, 6th December 2006, only to return to Suva on 4 October 2007.

In his evidence Mr Qarase said he returned on 1 September 2007.

I must confess that academic lawyers (and practising lawyers and judges) not familiar with the events of 5 December 2006 will not be a position to do a thorough and just critique of the High Court judgment because Qarase’s legal arguments are woefully absent in the judgment.

Also, unlike Qarase who agreed to testify, both the President Ratu Josefa and Bainimarama (who flew all the way to New York to explain his actions to the UN General Assembly), chose not to appear before the High Court and to be cross-examined about their roles in the events prior to, during, and after the 2006 coup.

According to Qarase’s affidavit to the High Court of 24 September 2007, the following chain of events occurred: (1) That since 6 December 2006, my freedom of movement was confined to my home island of Vanuabalavu in the Lau Group. My wish to return to Suva was prevented by threats against my safety and liberty regularly announced publicly by the First (Bainimarama) and Second (RFMF) Defendants in the local media. The only airline that services my island, Air Fiji, was reluctant to transport me out of Vanuabalavu for fear of Military reprisals. On 4 January, 2007 I received a telephone call from a person who identified himself as a Major Sitiveni Qilio in the Second Defendant warning me that I would be arrested by the Second Defendant, if I returned to Suva.

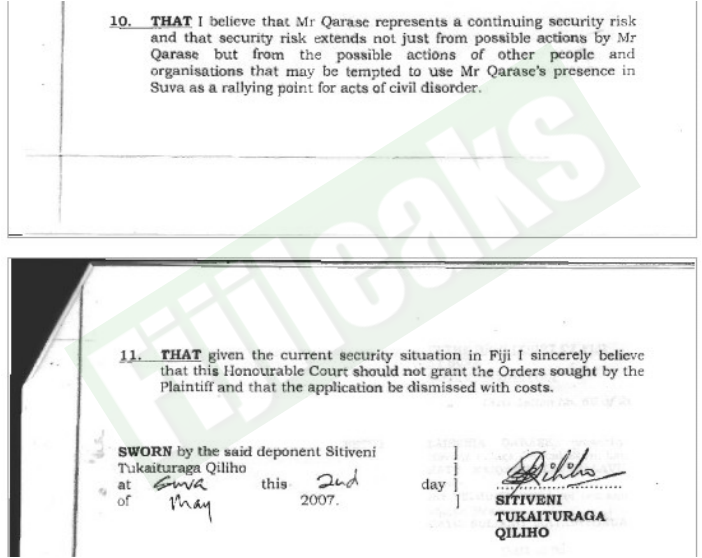

(2) That my application to this Court, through my lawyer, for orders to direct the First and Second Defendants not to impose restrictions on my freedom of movement guaranteed under the Constitution was opposed by the First and Second Defendants, and I crave leave to refer to their affidavit thereon sworn by one Major Sitiveni Tukaituraga Qiliho on 2.5.07, but this Honourable Court granted that order on 11.6.07, and I crave leave to refer to the said order.

(3) That despite the order of this Court described in paragraph 5 herein, and despite the fact that there was no state of emergency then existing, and despite the fact that there was no other legal restriction imposed upon me, the Chief Executive Officer of Air Fiji informed me by telephone on 28.8.07 that his airline was unable to transport me to Suva by a chartered flight on 29.8.07 as planned, because Air Fiji was warned by the Second Defendant not to transport me from Vanuabalavu. There was wide local and international publicity about and condemnation of these continuing efforts by the Second Defendant to restrict my freedom of movement, in particular regarding my return to Suva to help prepare for my case. I can understand why the Chief Executive of Air Fiji has denied his telephone confirmation to me that he was instructed by the Second Defendant not to transport me to Suva. I was to charter one of their aircraft, and his Company needed the business, and this made his initial confirmation about his inability to transport me to Suva more credible, i.e. out of fear of possible military reprisals.

(4) That I also received a phone call on 28.8.07, in which a person who identified himself as calling from the Fiji Military Forces Camp threatened that I would be killed on arrival, if I returned to Suva.

The First and Second Defendants have denied and continue to deny any role in restricting my freedom of movement and the threats against my safety and liberty conveyed to me by telephone.

Strangely, coincidentally, Fiji Air’s reluctance to accept our request to charter one of their aircraft to transport me to Suva was refused on the same day.

I sincerely believe that the Second Defendants have had difficulty not only in denying that these events did take place, but more importantly in denying that they knew.

Moreover, the silent majority of the public of Fiji are familiar with this tactic of denials by the First and Second Defendants about their regime of violations of human rights since 5th December, 2006.

(5) That as a result of these difficulties, I did not manage to return to Suva by chartered flight until 1.9.07.

However, immediately before and since returning to Suva, incidents which continue to demonstrate the Second Defendant’s determined effort to restrict my freedom of movement, freedom of expression, freedom of association, and other human rights principles enshrined in the Constitution.”

In its judgment the High Court relied on the invisible powers of the English kings on the question of prerogative in sanctioning the President’s actions.

But we might want to recall that in the Magna Carta there is a ringing expression of freedom for mankind in the world over:

“No free man shall be taken or imprisoned or deprived or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor will we go or send against him, except by the lawful judgments of his peers or by the law of the land. To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.”