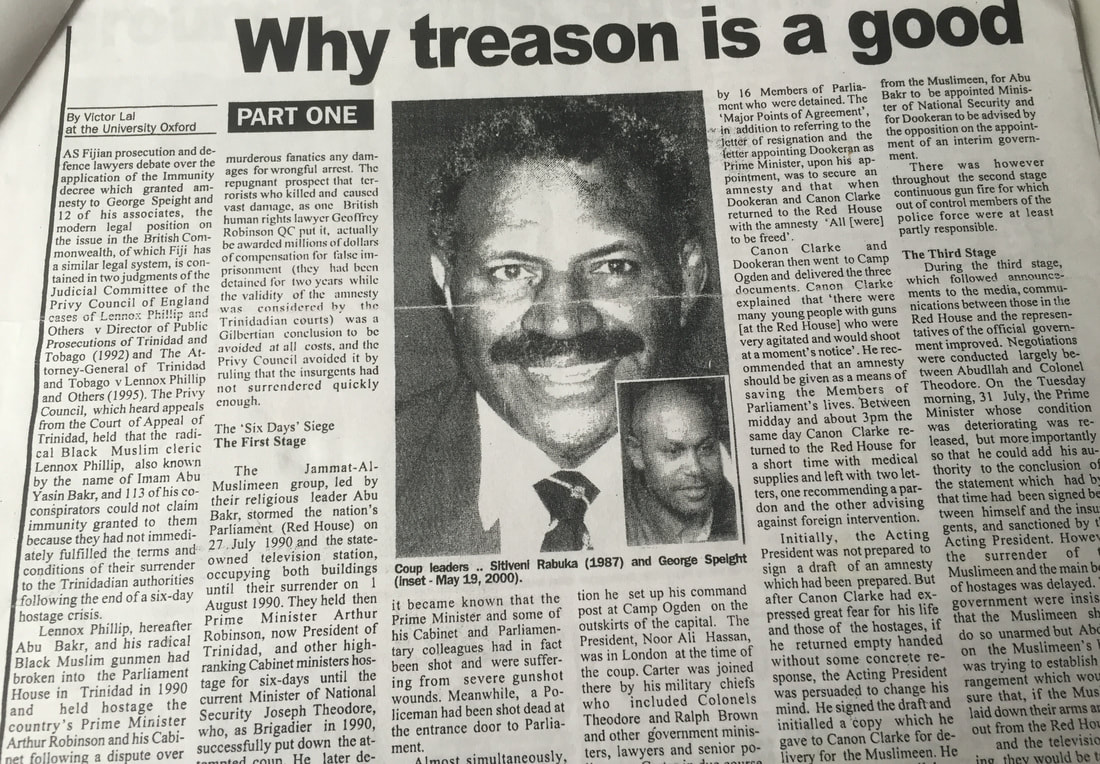

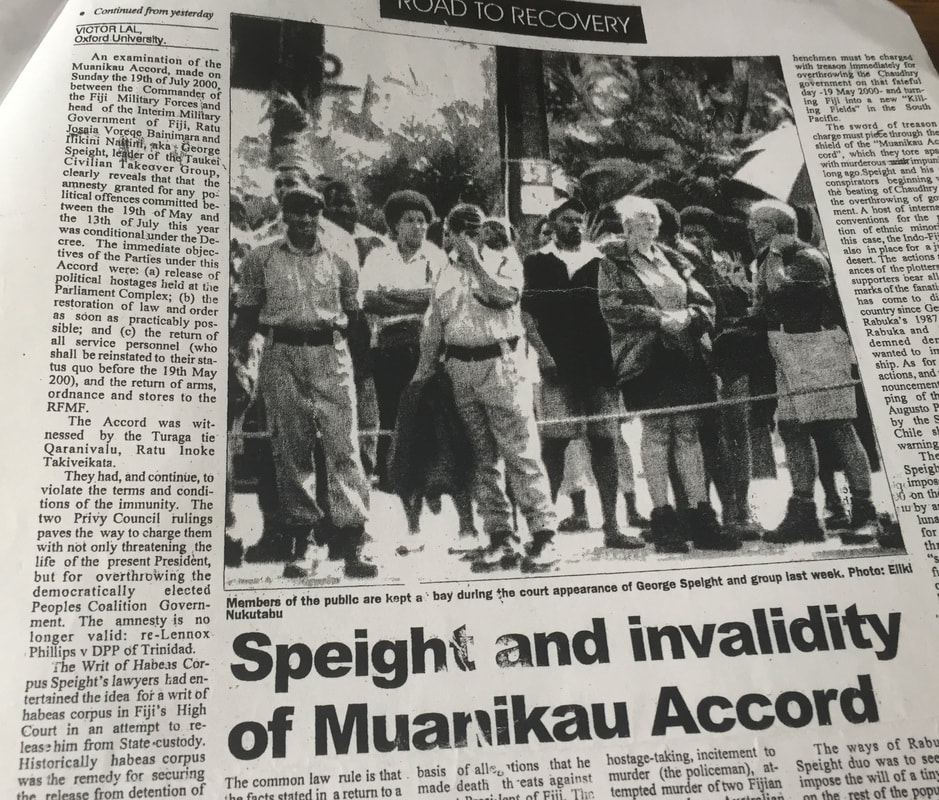

The RA suspects currently facing trial under the Bainimarama government are following in the footsteps of the ROTUMAN SEVEN who were hauled before the Magistrate's Court and convicted following Rabuka's treasonous coups. While overturning the ROTUMAN 7's convictions for sedition, the Fiji Court of Appeal judges argued that a charge of sedition could not be used to curtail “genuine political dissent which is often the ground from which democracy grows”. Sitiveni Rabuka had got the Rotuman 7 charged after they had refused to concede that Rotuma automatically followed Fiji into his post coup Republic. The RA SIXTEEN currently on trial at the Lautoka High Court are charged with sedition as they are alleged to have wanted to form the Ra Sovereign Christian State. It is worth noting that Western separatism is nothing new in Fiji. Following the George Speight failed coup, there were threats from western and northern Fijians to create breakaway governments, with our founding Editor-in-Chief VICTOR LAL arguing in Fiji's Daily Post (July 8, 2000): "There is no legal proscription in international law on the secession of western or other provinces of Fiji...Given the facts to date, the western part of Fiji has all the ingredients for recognition in international law in the immediate future if, and when, it decides to breakaway from Fiji. It is hoped that George Speight and his supporters are made aware of the grave danger of secession as a result of their irredentism and racist adventurism. In the 1987 coups, ROTUMA had nearly taken the first step in the secessionist direction. There is no legal proscription on secession.".

See below Justice Michael Scott's judgment on the ROTUMAN SEVEN

HIGH COURT OF FIJI

AFASIO MUA & OTHERS

v

THE STATE

[HIGH COURT, 1991 - (Scott J), 4 June]

Appellate Jurisdiction

Crime - offence - sedition- effect of failure to consider statutory defences - whether proof of sedition requires proof of incitement to violence.

The Appellants were convicted of sedition. On appeal against conviction the High Court HELD: (1) the magistrate's failure to consider the statutory defences to the charge was fatal to the convictions and (2) that there was no evidence of incitement to violence and accordingly no proof of sedition.

Cases cited:

Boucher v The King (1951) 2 DLR 369

Bullard v R. (1957) AC 635,642

Comptroller of Customs & Excise v Burns Philp (SS) Co. Ltd. 17 FLR 1

DPP v Chike Obi (1961) ANLR 186

DPP v Masson (1972) MR 204

Issa v R (1962) EA 186

Kachikwa (1968) 52 Cr.App.R. 538,543

Kedar Nath Singh v The State of Bihar 1962 AIR SC 955

Niharendu Dutt Maiumdar v King Emperor 1942 AIR SC 22

R. v Falconer-Attlee (1973) 58 Cr.App r. 348

R. v Jai Chand 18 FLR 101

R. v Pilcher & Ors (1974) 60 Cr.App.R. 1

R. v Sullivan (1868) 11 Cox CC 44, 45

R. v Wallace-Johnson 5 WACA 56

Regina v Chief Metropolitan Magistrate ex parte Chaudhary [1990] 3 WLR 986

Rex v Millien (1949) MR 35

Shannon Realties v (Ville de) St. Michel [1924] AC 185 192

Wallace-Johnson v R [1940] 1 All E.R. 241

Appeal against convictions entered in the Magistrates' Court.

T. Fa for the Appellants

I. Mataitoga (Director of Public Prosecutions) for the Respondent

Scott J:

This is an appeal by the seven appellants against convictions for the offence of sedition entered against them by the District Officer's Court Rotuma (A.M. Seru Esq., Chief Magistrate) on 27 October 1989.

Under the provisions of section 308(3) of the Criminal Procedure Code such an appeal may be in respect of a matter of fact as well as a matter of law.

The statement and particulars of offence were as follows:

Statement of Offence

Sedition: contrary to section 66(1) (a) and section 65 (i) (iv) of the Penal Code Cap. 17.

Particulars of Offence

Afasio Mua, Hiage Apau, Jioji Aisea, Fredi Emosi, Uafta Veresoni Elario, lane Savea, Ian Crocker, Vesesio Mua and two others on or about the 15th day of April 1988 at Juju, Rotuma in the Eastern Division held a meeting with seditious intention.

Upon conviction the appellants were each fined the sum of $30 and bound over for two years to be of good behaviour.

The facts and background as substantially agreed may be summarised as follows:

On 14 May 1987 there occurred a military coup d'état in" Fiji. On 16 May 1987 the Rotuma Council met and a message of support for the coup was sent to the Governor General. It appears that the stance adopted by the Council had the broad but not unanimous support of the people of Rotuma .

For some years some inhabitants of Rotuma had been striving for greater autonomy for Rotuma or even complete independence. They came together and formed their own clan the Mulmahau Clan under the leadership of Henry Gibson also known as Gagaj Sau Lagfatmaro. Mr Gibson's claim to the title of chief was not recognised by the seven traditional and duly appointed District Chiefs of Rotuma who are ex-officio members of the Rotuma Council ( Rotuma Act, Cap. 122 section 12(1) (a)).

In about June 1987 Mr Gibson sent representatives of his clan to visit the paramount chief of Rotuma , Gagaj Maraf Solomoni and to give him the message that Rotuma should become independent. This request was rejected.

On 25 September 1987 the 1970 Constitution of Fiji was abrogated by military decree and on 7 October 1987 Fiji was declared a Republic.

In about the beginning of April 1988 the appellant Afasio Mua received a letter from Mr Gibson requesting him to call a meeting of the Mulmahau Clan to elect seven new chiefs. Although there was some dispute to the intended nature of these seven new chiefdoms the prosecution evidence tended to establish that the seven chiefs were to replace the seven traditional district chiefs already referred to.

On 15 April 1988 a meeting was held at Juju, Rotuma , the subject of the charge. The meeting was held in a private house and therefore was not apparently very large. In addition to the seven appellants there was an unknown number of other persons present. Two decisions were taken. The first was that the seven appellants were elected chiefs and the second was that a letter would be sent to His Excellency the President of Fiji advising him of the results of the election. On 26 April 1988 the following letter was received by the Office of the President:

(Exhibit 3A)

C/o Kausakmua

(Chief Ministers for Gagaj Sau Lagfatmaro)

Kalvakta,

Noatau,

Rotuma .

MULMAHAU CLAN ELDERS

Private Box

Post Office

Rotuma

15.4.88

The President of the Republic of Fiji

Government Buildings

SUVA

Your Most Honourable,

This is a formal letter declaring publicly known that the terms of the 7 former chiefs of Rotuma have been suspended from office for misuse of powers invested upon them in joining the Republic of Fiji without prior consultation of the people of the Island of Rotuma .

The 7 newly legally representatives from the only legal cabinet of Rotuma are as follows and only will be recognised now.

1.Noatau DistrictHiagi Apao

2.Oinafa DistrictJioje Aisea

3.Malhaha DistrictFereti Emoase

4.Itutiu DistrictMausio Managreve

5.Juju DistrictGagats Uafta Versoni

6.Pepejei DistrictIane Savea

7.Itumuta DistrictGagats Gargsau Mose

We refer to the Deed of Cession of Rotuma to Her Majesty Queen Victoria of Great Britain in 1881 stating very clearly that the 7 chiefs cannot finalise any decisions without prior consultations and approval from the people of Rotuma .

We regret very much for the steps taken and apologise for any inconveniences caused.

Respectfully Yours,

Chairman,..Hiage Apao (Signed) Security .... Afasio Mua (Signed)

cc. The Prime Minister of the Republic of Fiji

H.R.H. Queen Elizabeth the Second of Great Britain

The Prime Minister of New Zealand

The Prime Minister of Australia

Fiji Times Media

Radio Fiji

F.M.96

OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

REPUBLIC OF FIJI

26.4.88

A second letter apparently enclosed was with the first was also received by the President's Office as follows:

(Exhibit 3B)

"C/o Kausakmua (Chief

Ministers for Gagaj Sau

Lagfatmaro)

Kalvakta,

Noatau,

Rotuma .

MULMAHAU CLAN ELDERS

Rotuma Island

15.4.88

The President of The Republic of Fiji

Government Buildings

SUVA

Your Most Honourable,

The undersignees are the only legally elected chiefs of Rotuma representing the Island today and recognised are known as:-

1.Hiagi Apao...(Signed)Hiagi Apao...(Signed)

2.Jioje Aisea...(Signed)Jioji Aisea...(Signed)

3.Malhaha DistrictFereti Emose...(Signed)

4.Itutiu DistrictMausio Managreve...(Signed)

5.Juju DistrictGagats Uafta V...(Signed)

6.Pepejei District.Iane Savea...(Signed)

7.Itumuta DistrictGagats Gargsau Mose...(Signed)

Respectfully Yours,

Chairman Magi Apao...(Signed)

Security Afasio Mua...(Signed)

cc. The Prime Minister of the Republic of Fiji

H.R.H. Queen Elizabeth the Second of Great Britain

The Prime Minister of New Zealand

The Prime Minister of Australia

Fiji Times Media

Radio Fiji FM 96"

It will be noted that both letters

(i) bear at their foot an intention that they be copied, inter alia, to the Fiji Times Media (sic)

and

(ii) are signed by each of the appellants with the exception of appellant No. 7 Visesio Mua.

Shortly after the receipt of the letters by the Office of the President one or more articles appeared in the Fiji Times, a newspaper which circulates in Rotuma . Although the newspaper was not tendered the District Officer Rotuma , Tui Wesley Malo (PW7) told the Court that the Fiji Times "published the election of seven chiefs". Kaiko Kauata (PW8) also told the Court that he "heard that they (the seven chiefs) were installed and read in the newspapers".

The District Officer who had been in Suva returned to Fiji. On his return he found the situation was tense. Although "there was no violence traditional chiefs were not happy with what had happened". He "wrote to HQ and told them of tense situation and would need assistance. On 30th April 1988 a police party arrived."

PW8 told the Court that "people were disturbed, angry and have fear because of news going around that new chiefs will rule the Island". Another witness Naniu Vilisoni (PW9) told the Court that "we were shocked sad and angered because of what the papers say and that our elected chiefs were suspended". He however went on to say that "no doubt my chief was still chief. What I read was not true. I was insulted. Much insulted if not a joke. Difference here is that claims were made and the paper printed it that Malhaha has a new chief".

Between 2 and 5 May 1988 the appellants were each interviewed by the police under caution. The precise words of the caution varied to some extent but were typically (interview of Hiage Apau) as follows:

"I wish to interview you in connection with a letter that you and other Rotumans wrote to the President of Fiji on 15th April 1988 to say that you have appointed yourself as chairman of the Council of Rotuma without any legal authority. This has caused disaffection amongst the people of Rotuma . You are not obliged to say anything unless you wish to do so and whatever you say will be taken down in writing and may be given in evidence".

Each of the seven appellants gave statements to the police and these were tendered. Each appellant admitted having been present at part or all of the meeting at Juju and having agreed that a letter be sent to the President. Six admitted signing the letter.

When it was put to the appellants that they must have been aware that there would be a likelihood of opposition (in some cases the word "disaffection" was used) as a result of what they had decided, some agreed but some disagreed. It is clear from the statements that some of the appellants were claiming to have acted as they did merely because they were told to do so by Mr Gibson. Some had a clearer appreciation of the likely consequences of their action. Thus Hiage Apau who chaired the meeting agreed when it was put to him by the interviewing officer that he had "blindly signed" the letter whereas Visesio Mua admitted that he knew that "the people" would not like what they had done.

A similar range of views was expressed when the appellants were charged. Only three charge statements were tendered. While Afasio Mua gave a concise statement of his political views, Uafta Veresoni apologised and sought pardon whereas Visesio Mua said he had done what he had been told to do.

After a trial lasting eight days between 12 December 1988 and 26 October 1989, Judgment was delivered on 27 October 1989 convicting all seven appellants as charged. Appellants appealed on 22 November 1989, additional grounds of appeal were filed on 4 April 1991 and the appeal was heard on May 1991.

At the hearing of the appeal I was much assisted by comprehensive and scholarly written submissions filed both by Counsel for the Appellants, Mr T. Fa and by the Director of Public Prosecutions, Mr I. Mataitoga for which I am most grateful.

The 14 grounds of appeal were argued together in three groups and as three groups they were described. Grounds 1, 3, and 6 were not pursued.

Group 1consisting of Ground 7 was a submission that the trial magistrate erred in law and in fact in ruling at the end of the prosecution case that there was a prima facie case against each of the appellants.

Group 2consisting of Grounds 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 together with the original ground of appeal of 22 November 1989 together amounted to a submission that the learned that magistrate erred in law and in fact when he found that the case against the appellants had been proved beyond reasonable doubt.

Group 3comprising Ground 2 was a submission that the learned trial magistrate had misdirected himself by failing to consider and exclude the statutory defences opened to the appellants and that accordingly the conviction could not stand.I will take Group 3 first.

The relevant parts of section 65 of the Penal Code are as follows:

Section 65 - (1) "A seditious intention" is an intention –

(iv) to raise discontent or disaffection amongst .... inhabitants of Fiji.

But an act speech or publication is not seditious by reason only that it intends –

(a) to show that Her Majesty has been misled or mistaken in any of her measures; or

(b) to point out errors or defects in the Government or constitution of Fiji as by law established or in legislation or in the administration of justice with a view to the remedying of such errors or defects; or

(c) to persuade Her Majesty's subjects or inhabitants of Fiji to attempt to procure by lawful means the alteration of any matter in Fiji as by law established; or

(d) to point out, with a view to their removal, any matters which are producing or having a tendency to produce feelings of ill-will and enmity between different classes of the population of Fiji."

It will be noted that for the purposes of the Code Rotuma is a part of Fiji (Interpretation Act, Cap. 7, section 2) and that the references to Her Majesty and Her Majesty's subjects must be read as references to the President of Fiji and Fiji citizens by virtue of the Existing Laws Decree 1987.

Paragraphs (a) to (d) of the sub-section are very wide and comprehensive and have the effect of imposing considerable limitations on the applicability of paragraphs (i) to (v). They are exceptions to the section. The onus of establishing such exceptions lies on the defence (Criminal Procedure Code (Cap. 21) section 144). If established on the balance of probabilities such exemptions represent a complete defence to the charge.

In a Magistrate's Court the Resident Magistrate, sitting as he does alone, must perform the functions of both Judge and Jury. He must therefore analyse the various legal and factual issues and his judgment must contain these points and his determination upon them (Criminal Procedure Code, section 155(1)). A mistake of law will have the same effect as a misdirection of law to a Jury and a non direction of law will have the same effect as a failure direct a Jury on a matter which calls for direction.

Among the matters which must be determined is whether the party upon whom the burden of proof lies has discharged that burden. The primary burden of course rests upon the prosecution and the learned Chief Magistrate referred to that burden in his judgment. He said:

"I have reminded myself that the prosecution has a duty to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt .... Should there be any doubt at all, even the slightest, that should be resolved in favour of the accused".

He then analysed the basic ingredients of the offence, compared these with the evidence, found himself satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the offence had been proved and proceeded to conviction.

Apart from a section in the judgment dealing with the seventh appellant which is not relevant to this group of grounds of appeal the only passage referring to the evidence led for the defence reads as follows:

"All accused persons statements were recorded by police and exhibited. They were taken without any threat being made or promises given or any kind of inducement made to them. They had opportunity to correct, add to, or vary their statements.

All accused persons gave evidence on oath. There were slight variations to their version of their appointment. Some say they were to be chiefs, not of Rotuma , but chiefs of the Mulmahau Clan in the districts allocated to them. Some say they were to be elected leaders of the Mulmahau Clan only and not as chiefs. They also agreed that they held a meeting on or about 15/4/88 and the substance of what was discussed was reduced to writing as exhibited in Exhibits 3A and 3B. The documents, as I reiterate what I said in my ruling yesterday, speak for themselves."

I have already briefly referred to the statements and pointed out that they revealed a range of attitudes to the questions being put. A number of examples will illustrate.

Hiage Apau, while accepting that he had been misguided stated that at the time the meeting was held he was under the impression that the election was legal. He did not think that the suspended chiefs would rise in response.

Afisio Mua, evidently more of an historian, indicated that the purpose of the meeting was to take a step towards independence. Although the precise meaning of the interviews in translation is not always as clear as one might wish, he apparently supported the view that what had been done was lawful.

Fredi Emosi did not agree that what had been done would "bring disaster to the people of Rotuma ". He did not accept that what had been done was in breach of the law.

Visesio Mua told how he had attempted to gather support for the view that Rotuma should be independent.

Uafta Elario stated that he did not sign his name "to cause disaffection". He did not agree to the letter in the form it was typed. Furthermore, he disagreed that the purpose of the meeting was to elect new chiefs for Rotuma as opposed to leaders of their own party.

In his charge statement Afasio Mua said:

"I wish to state that myself and my supporters did this because we wanted our Island of Rotuma to retain its ties with England as our forefathers had signed the Deed of Cession in 1881. Furthermore we did this on our instructions that came from New Zealand and other parts of the world that officially declare us. We did this as we believe what Gagaj Sau Lagfatmaro had told us is correct".

Each of the appellants gave evidence on oath. The first six appellants denied that they-had appointed themselves as chiefs for Rotuma as opposed to chiefs in the Mulmahau Clan. The seventh appellant Visesio Mua denied being at the meeting at all during its formal parts, claimed not to have agreed to the letter and of course did not, as a matter of fact, sign it.

As will be seen from the portion of the Judgment already quoted, the learned Chief Magistrate did not refer to the statutory defences at all. Neither did he refer to the general points of dispute raised by the appellants. In the case of Visesio Mua he did not specifically reject his defence.

He did, it is true, refer to section 65(2) of the Penal Code which reads:

"In determining whether the intention with which any act was done, any words were spoken, or any document was published, was or was not seditious, every person shall be deemed to intend the consequences which would naturally follow from his conduct at the time and under the circumstances in which he so conducted himself."

He took the view that the existence of discontent and disaffection had been proved by the prosecution, that they had as their source the publication of the letters to the President, that they had "naturally followed" from the publication and that therefore the consequences had to be deemed to be intended by the appellants.

This reasoning, however, overlooks the fact that even if discontent and disaffection are proved to have occurred it does not follow that an offence is proved to have been committed if all that was actually intended was one of the intentions set out in sub-paragraphs (a) to (d). Accordingly, paragraphs (a) to (d) must be excluded before section 65(2) can fall to be considered.

Now it is true that in his closing address to the court Counsel for the appellants did not directly refer to paragraphs (a) to (d) of section 65(l). He did, however, submit that what had been done did not amount to subversion, that no actual attempt had been made to take over the Rotuma Council and that generally what had been proved to have occurred did not amount in law to sedition.

In my view the defences statutorily and in law open to the appellants should each have been considered and rejected before the learned Chief Magistrate could properly move on to conviction. As has been seen, the statements and the evidence of the appellants showed that there was at least an argument that the appellants were of the view that the status of Rotuma had been wrongly decided, that the laws of Rotuma should be changed and that the existence of these matters was a source of ill-will and enmity. Whether the argument was strong or weak, valid or invalid was not the point. The question which the failure to address these statutory defences left unanswered was whether the court was satisfied that the appellants were not merely exercising their legitimate rights preserved for them by paragraphs (a) to (d) of Section 65. That the defences may not have been raised at all or may only have been obliquely referred to does not affect the position in law. A failure to consider a statutory defence is an omission of an extremely important direction (R. v. Falconer-Attlee (1973) 58 Cr. App. R. 348) and this is so whether or not the defence has actually been raised (Kachikwa (1968) 52 Cr. App. R. 538,543 and Bullard v. R [1957] AC 635,642). Whether raised or not such a defence, being statutory, must specifically be rejected before it can be safe to convict. Group 3 of the grounds of appeal succeeds.

Group 2 of the grounds of appeal may be taken next. Counsel for the appellants advanced two principal arguments in support of the submission that the learned Chief Magistrate erred in law and in fact in finding the case against the appellants proved beyond reasonable doubt. It was submitted first that the sending of the letter to the President was not a seditious act and that accordingly the meeting at Juju was not held with a seditious intent and secondly that such discontentment as may have been proved to have occurred in Rotuma was not proved to have occurred as a result of the sending of the letter to the President or of its publication in the Fiji Times.

The first submission raises the very important question as to the meaning of sedition in Fiji. I was advised from the Bar that this is the first case of sedition to have been prosecuted in Fiji.

The dilemma which has faced the courts in other jurisdictions is this: What limits are imposed on the freedom of expression by the law of sedition given the fundamental freedom of expression enshrined in the constitution?

As previously mentioned, the 1970 Constitution was abrogated on 7 October 1987. On 1 February 1988 section 12 of the 1970 Constitution was replaced by section 11 of the Protection of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms of the Individual Decree 1988. This Decree is therefore the relevant protective law for the purposes of this appeal although by virtue of its similarity with the parallel provisions in the Constitution much of what is hereinafter set out will apply to all three documents. Section 11 reads as follows:

"Protection of freedom of expression

11. - (i) Except with his own consent, no person shall be hindered in the enjoyment of his freedom of expression, that is to say, freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart ideas and information without interference, and freedom from interference with his correspondence.

(2) Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection 1 of this section no person shall without reasonable justification or excuse cause:-

(i) any expression to be made that would tend to lower the respect, dignity and esteem of institutions and values of the Fijian people, or, that would tend to show disrespect to the Great Council of Chiefs and the traditional Fijian System and titles;

(ii) any expression to be made that would tend to lower the respect, dignity and esteem of institutions and values other races in Fiji, or, that would tend to show disrespect to their institutions and traditional systems;

and any person making any such expression may be liable for Sedition under the Penal Code.

(3) Nothing contained in or done under the authority of any law shall be held to be inconsistent with or in contravention of this section to the extent that the law in question makes provision -

(a) in the interests of defence, public safety, public order, public morality or public health;

(b) for the purpose of protecting the reputations, rights or freedoms of other persons or the private lives of persons concerned in legal proceedings, preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, maintaining the authority and independence of the courts, or regulating the technical administration or the technical operation of telephony, telegraphy, posts, wireless broadcasting or television; or

(c) for the imposition of restrictions upon public officers, except so far as that provision or, as the case may be, the thing done under the authority thereof is shown not to be reasonably justifiable in A society that has proper respects for the rights and freedoms of the individual."

It is clear that if a literal interpretation of section 65 is adopted then very substantial inroads on the freedom of expression guaranteed by the Decree and by the 1970 and 1990 Constitutions would be the result. A simple example will illustrate the point.

Let us suppose that a well financed pressure group decided to mount a campaign in Fiji with its principal objective the outlawing of some controversial activity such as smoking, therapeutic abortion or the sport of boxing. It is probable that such a campaign would lead to feelings of ill-will and hostility between different classes of the population of Fiji and would therefore prima facie fall foul of section 65 (1) (v) of the Penal Code. Given section 65 (2) and the likelihood that these feelings of hostility and ill-will would have flown from such a campaign the mounting of such a campaign would appear on the face of it to constitute an act of sedition. Does this mean then that expression may be free only to the extent that it does not have as one of its consequences the occurrence of any of the events set out in paragraphs 65 (1) (i) to (v) of the Penal Code?

Two views of the meaning and effect of section 65 may be taken and these correspond to the two views which have been taken of the scope and limits of the laws of sedition as existing in countries with Penal Codes similar to our own.

The first view is that the Penal Code represents a complete and comprehensive statement of the law of sedition and must be interpreted in its own terms free from any glosses or interpolations derived from any expositions however authoritative of the laws of other jurisdictions. This view has its purest expression in the decision of the Privy Council in Wallace-Johnson v. R [1940] 1 All E.R. 241. Such an approach to the interpretation of the laws of Fiji was adopted in Comptroller of Customs & Excise v. Burns Philip (SS) Co. Ltd. 17 FLR 1 a case turning on the interpretation of the Customs Tariff Ordinance (Cap. 171 - 1967 Edition).

The inevitable effect of adopting such an approach would in my view be to accept the very substantial inroads into the freedom of expression guaranteed by the Constitution and by the Decree to which I have referred.

The second view starts from the fundamental freedoms enshrined in the Supreme Law of the Nation (see Section 2 of the 1970 and 1990 Constitutions of Fiji) and proceeds to an interpretation of the law of sedition which enables the latter to be operated without doing violence to the overall purpose of the former. The consequences of adopting the second view are that before the offence of sedition can be made out it must be proved that there was an incitement to violence against an institution of the state.

At the hearing of this appeal the Director broadly advanced the first approach as being correct while counsel for the appellants broadly advocated the second view. Both counsel very fairly acknowledged the difficulty of drawing a line between what was prohibited and what was guaranteed and I was most helpfully referred by counsel to a number of authorities supportive of both points of view.

The quest for a resolution to the question can best begin with the decision of Wallace-Johnson already referred to. This was an appeal against a conviction for sedition brought from the West Africa Court of Appeal which had dismissed an appeal from the Supreme Court of the Gold Coast entered against the appellant in 1936. The appellant argued that a prosecution for the offence of sedition could not succeed unless the words complained of were themselves of such a nature as to be likely to incite violence and unless there was positive extrinsic evidence of seditious intention. The Board rejected this argument and held that there was nothing in the Code to suggest that its interpretation could be approached in the light of decisions reached by the English and Scottish Courts under Common Law. Wallace-Johnson is important since the relevant parts of the Criminal Code of the Gold Coast colony were closely similar to the relevant parts of Section 65 of our Penal Code. It should however be noted that the Gold Coast colony had no constitution containing the fundamental freedoms enjoyed by the citizens of Fiji and accordingly the dilemma posed by the present case did not fall to be addressed by their Lordships.

Wallace-Johnson was followed by the Supreme Court of Mauritius in the case of Rex v. Millien (1949) MR 35, it being again held that the proof of seditious intent did not require proof of an intention to incite violence. But, in 1972, Mauritius having by then achieved its independence together with a constitution embodying fundamental freedoms including the freedom of expression, the Supreme Court found it necessary to depart from its earlier approach and to interpret the Mauritius Penal Code Ordinance in a manner broadly reflective of the approach adopted by a number of other jurisdictions both Common Law and Code. The Court held (DPP v Masson (1972) MR 204) that the incitement to disorder or the tendency or likelihood of public disorder or the reasonable apprehension thereof was an essential ingredient of the offence of sedition under the Mauritius Penal Code. Although I do not have access to the entire Mauritius Penal Code Ordinance it is clear from the cases referred to that its wording is similar to that of the Penal Code of Fiji.

In reaching its decision the Mauritius Supreme Court placed heavy reliance on a number of decisions of the Federal and Supreme Courts of India both before and after independence which had considered previously the question now before the Court namely the interpretation of a Penal Code Offence of Sedition given the fundamental freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution.

In Kedar Nath Singh v. The State of Bihar 1962 AIR SC 955 the Supreme Court of India referred to the two views previously mentioned. In declining to follow Wallace-Johnson the Court observed that if the meaning given by the Privy Council were adopted the section would be much beyond the permissible limits of restrictions which the State was empowered to impose under Article 19(2) (Freedom of Expression) of the Constitution of India. But, on the other hand, if the meaning given to the section by the Federal Court in Niharendu Dutt Maiumdar v King Emperor 1942 AIR FC 22 were accepted the section would be in accordance with the Constitution. In Niharendu's case the Federal Court had held that the gist of the offence of sedition was incitement to violence or the tendency or the intention to create public disorder by word spoken or written which have the tendency or the effect of bringing the Government established by law into hatred or contempt or creating disaffection in the sense of disloyalty to the State. In other words the Federal Court brought the law into line with the Law of Sedition in England.

In reaching its decision the Supreme Court, following a number of decisions of Supreme Courts of other jurisdictions, also prayed in aid the principle of the presumption of constitutionality, that is to say where a provision of law is capable of two interpretations one of which makes it constitutional and the other unconstitutional then the interpretation which makes it constitutional is to be preferred.

It should be noted that the present Penal Code of Fiji is the successor to the original Penal Code of Fiji, Ordinance 18 of 1944 which itself, in common with most Penal Codes of the former Pacific and African colonies of Britain was derived from and broadly followed the Penal Code of India (Act XLV of 1860).

By comparison with the decision in Kedar Nath Singh and DPP v. Mason a decision of the Federal Supreme Court of Nigeria, DPP v. Chike Obi (1961) ANLR 186 must be referred to. The Federal Court was faced with the same question of reconciling the Constitution with the Penal Code. Section 50(2) of the Code including the statutory defences, was in precisely the same terms as Section 65 (1); The Constitution of Nigeria also guaranteed freedom of expression. The Court held that the statutory defences constituted a sufficient protection of the guaranteed rights and that accordingly Section 50(2) was not invalidated by the Constitution. However, in later declining to follow the course adopted by the Federal Court of Nigeria the Supreme Court of Mauritius pointed out that there is to be found in the judgment of the Federal Court no mention of Kedar Nath Singh nor of the very important decision of the Supreme Court of Canada, Boucher v. The King (1951) 2 DLR 369 to which further reference will be made below. It is also clear that the Federal Court had in mind precedent established by itself or the doctrine of stare decisis. Thus, at page 192 Ademola CJF. said:

"In this respect it is necessary to point out that an incitement to violence is not a necessary ingredient of the offence. This has been laid down in R v. Wallace-Johnson 5 WACA 56 at page 60 and this decision has been followed in all our cases of sedition in Nigeria."

This Court is not similarly constrained.

The question now is what view of the law of sedition should be taken in Fiji? I have come to the conclusion that the correct view is the second. I have come to this view for four reasons.

First, I accept with respect, the correctness of the reasoning behind the decision in Kedar Nath Singh and DPP v. Masson. The Penal Code of Fiji which predates both Constitutions and the Decree must be interpreted in their light and so as not to do violence to their plain meaning. The need for consistency between the penal Code and the Supreme Law of the State is particularly evident. As has been said:

"Where alternative constructions are equally open that alternative is to be chosen which will be consistent with the smooth working of the system which the statute purports to be regulating; and that alternative is to be rejected which will introduce uncertainty friction or confusion into the working of the system."

Shannon Realties v. (Vlle de) St. Michel [1924] AC 185 192.

Second, if the first view were to be taken then it would be impossible for a citizen of Fiji to know with reasonable precision where the limits on his freedom of expression lay. It need hardly be stated that such a situation is quite unacceptable. The Director, responding to the simple illustration set out above met the difficulty by characterising sedition as being a crime against society, nearly allied to that of treason and submitted that since a campaign of the type I have referred to would not involve the deliberate stirring up of opposition to the authorities of State, no sedition would be involved. With respect I am of the opinion that to adopt such an approach, however consistent it may be with the approach adopted by other jurisdictions (see E.G.R. v. Sullivan (1868) 11 Cox CC 44, 45) is to place a gloss upon the words of the Section which is precisely what, on the first view of the meaning of the Section, is not allowed.

Third, Section 3 of the Penal Code, the interpretation section, reads as follows:

"This Code shall be interpreted in accordance with the principles of legal interpretation obtaining in England and expressions used in it shall be presumed, so far as is consistent with their context, and, except as may be otherwise expressly provided, to be used with the meaning attaching to them in English Criminal Law and shall be construed in accordance therewith".

Now, although there is in England no Code offence of sedition, the basic question as to when behaviour becomes seditious is in both jurisdictions the same. The object both of Common Law and the Penal Code is to prevent public mischief while at the same time allowing legitimate dissent. As has been pointed out by this Court (R. v. Jai Chand 18 FLR 101) the Privy Council is not the repository of English Common Law and a decision of the Board, though of the highest persuasive authority may not be binding in Fiji. The abolition of appeals to the Privy Council from the Courts of Fiji is perhaps also relevant. It seems to me that the correct approach, bearing in mind the difficulties involved in the alternative view, is to interpret section 65 in a way which both accords with the interpretation of the English courts and which avoids the uncertainty to which I have already referred.

Fourth, the result of the judicial interpretation of the Law of Sedition by the highest courts overseas has been in the great majority of cases to restrict its operation to instances of incitement to violence against this State or its institutions. The leading authority is Boucher v. The King supra wherein is to be found the most complete analysis of the nature and history of the development of the law of sedition. In that case the Supreme Court of Canada declined to follow Wallace-Johnson and specifically concluded that proof of an intention to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between different classes of subjects did not alone establish a seditious intention. Although the 1930 Criminal Code of Canada did not define sedition in exactly the manner it is defined in our Code the statutory defences (section 133A) are essentially the same and it will be noted that the specific conclusion of the Court dealt directly with the wording of section 65(1)(v) of our Penal Code. To constitute sedition the Court held that there had to be proof of incitement to violence for the purpose of disturbing constitutional authority. This approach which has been widely accepted was also recently approved by the divisional court of the Queen's Bench Division in Regina v. Chief Metropolitan Magistrate Ex Parte Chaudhary [1990] 3 WLR 986 and accordingly represents the law in England.

It will be seen that by favouring and adopting the second view the result is an interpretation consistent with the Supreme Law of the State, an interpretation which complies with section 3 of the Penal Code itself and an interpretation of the law which is precisely the same as that arrived at in other democratic states which share our Common Law background. In this context it should be noted that such restrictions on the protection of Freedom of Expression as are permitted under the Constitution of 1990 by section 13(2) are subject to the proviso that they are not to be shown not to be "reasonably justifiable in a democratic society".

In the present case I find no evidence of any incitement to violence by the appellants against the constituted authorities be they the office of the President, the Central Government or the Council of Rotuma . I find no evidence of any disaffection, that is, "political alienation or discontent, a spirit of disloyalty to the Government or existing authority" Oxford English Dictionary caused by the actions of the appellants. Given the inclusion of the reference to the Law of Sedition in the Decree (such reference, it will be noted, does not appear either in the 1970 or the 1990 Constitutions) I also find no evidence that anything done by the appellants had any tendency to lower the respect, dignity or esteem of the traditional chiefs of the Council of Rotuma . On the evidence it is clear that such ill-feeling as there was, was directed at the appellants themselves, which is not at all the same thing. I find that the learned Chief Magistrate erred in law in finding the offence of sedition proved.

Given my findings on Group 3 of the grounds of appeal and the legal element of Group 2 the remaining grounds may be shortly taken.

As to the error of fact complained of in Group 2 I find it sufficient to say that I have grave difficulty in seeing how the meeting at Juju, which after all was the subject of the charge, was shown to have been seditious at all. It was held in private. It resolved to send a letter to the President. The meeting then ended. Some time later a letter was sent. But it is not the letter which appears in the charge, it is the meeting and I am not at all persuaded that there was any evidence that the meeting itself was held with any seditious intent.

I also accept that there must be serious doubts over the correctness of accepting the results of the publication of the articles in the Fiji Times and on the wireless as having flown from what the appellants wrote to the President. Although marked for distribution to the Fiji Times there was no direct evidence at all that any of the appellants actually sent a copy of the letter to the Fiji Times. The article or articles which appeared were not tendered. It cannot be assumed that the cause of discontent was not journalistic comment of a sensational nature coupled with ill-informed gossip rather than the mere self-appointment of an insignificant group as chiefs, appointments which, it was conceded were not even recognised as being legitimate according to Rotuman customary law. No attempt was made to take over the workings of the Council. It is clear to me from the transcript that there was a deep confusion of thought on the part of some of the prosecution witnesses. The traditional chiefs were properly and understandably upset at what the seven had done but what they did in appointing themselves as chiefs though illegitimate was not illegal and as such provided no cause for interference by the Criminal Law.

As to Group 1 of the grounds of appeal, in view of the findings on Groups 2 and 3, examination of the position would be somewhat academic and is in my view unnecessary It should however be mentioned that in construing a section of the Tanganyika Code similar to section 2(10) of the Criminal Procedure Code the Appeal Court held that the decision whether or not to call upon the accused to make his defence was essentially a matter for the trial court and that an appellate court would not set aside a conviction solely on the ground that there was no case to answer. See Issa v. R. (1962) EA 186.

There remains the question of proviso (a) to section 319(1) of the Criminal Procedure Code. For the avoidance of doubt I have concluded that I am not satisfied that had the learned Chief Magistrate not so misdirected himself as I have found, the result of the case against the seven appellants would have been the same (see R. v. Pilcher & Ors. (1974) 60 Cr.App.R. 1, 6). Accordingly, I decline to apply the proviso.

In the result the appeals of the seven appellants succeed. The convictions are set aside. The fines if paid must be refunded.

I desire to add two postscripts. First, this case from hearing to appeal has taken over 3½ years to dispose of. I do not think this is a satisfactory state of affairs given that our Constitution guarantees the fundamental right to secure protection of law which includes a fair hearing within a reasonable time. Second, as is frequently mentioned by the authorities probably no crime other than sedition has been left in such vagueness of definition. What however is clear beyond all doubt and argument is that each State has a right and duty to protect itself and its citizens against incitement to violence, public disorder or unlawful conduct including unlawful expression. Thus, section 13(2) of our Constitution makes provision for restrictions on the freedom of expression inter alia in the interests of defence, public safety and public order. Nothing in this judgment should be taken as casting any doubt whatever upon these and similar provisions.

(Appeal allowed; convictions quashed)