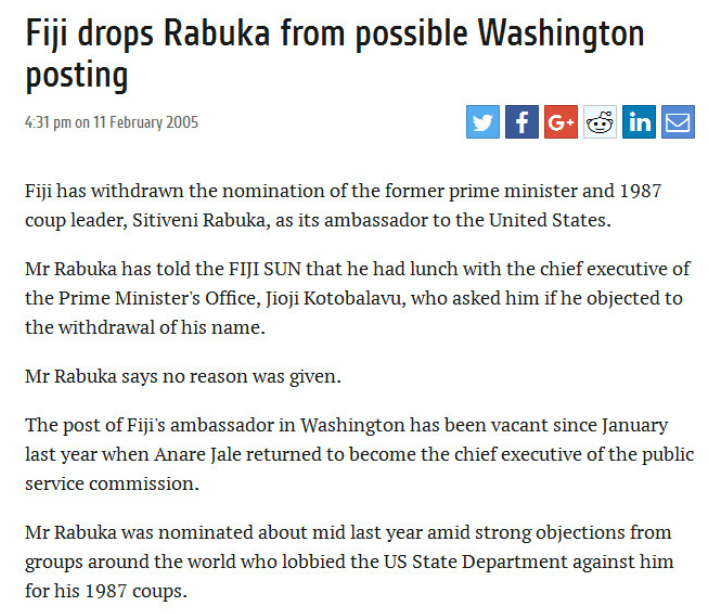

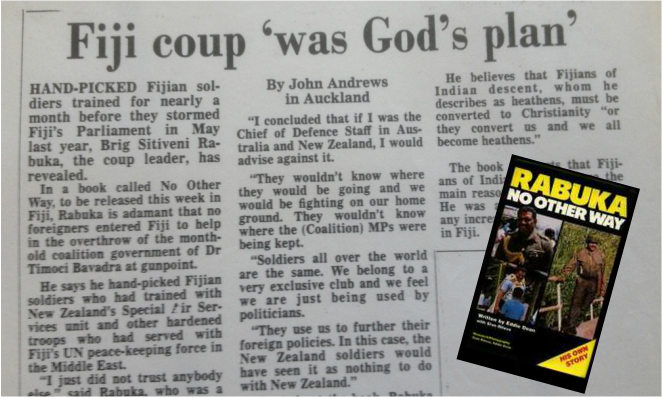

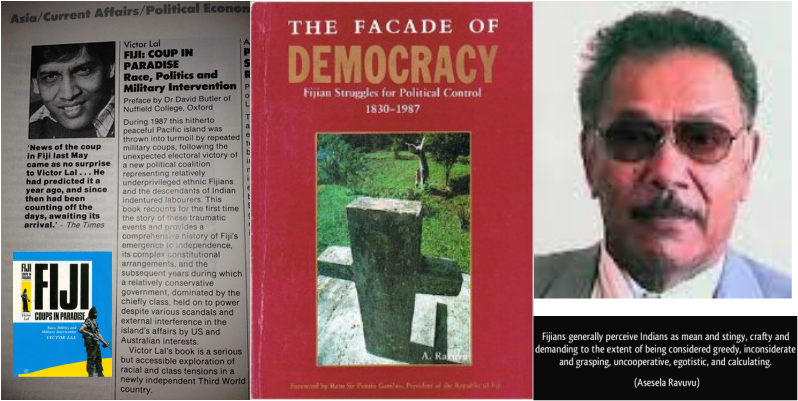

In 2005, Sitiveni Rabuka had been nominated as Fiji's Ambassador to the United States, sparking an international outcry. Among those leading the international campaign to arrest Sitiveni Rabuka and bring him to justice for the crimes against the Indo-Fijians following the 1987 racially motivated coups was Victor Lal, the founding Editor-in-Chief of Fijileaks. Below, we reproduce the article, on demand from many, on Rabuka's possible fate if he had accepted the appointment as Fiji's ambassador to the US to replace Anare Jale, now both vying to lead SODELPA.

Will the affable Anare Jale (reminding many of the late Dr Timoci Bavadra who had defeated Ratu Mara's Alliance Party and prompted Rabuka's racist coups) be the front-runner to lead the party?

Fijileaks: Unfortunately, Fiji Sun under the stewardship of Peter Lomas and Nemani Delaibatiki (two former colleagues of Victor Lal who had also become victims of Rabuka's 1987 coups after the old Fiji Sun of the same name had been shut down for refusing to operate under military censorship) have removed all of Victor Lal's columns from the paper's archive, dating back nearly twenty years! Is it to appease the current Bainimarama-Khaiyum dictatorship in Fiji? But who can blame them for the sacrilege inflicted to his columns, many now lost for good, for he did not keep copies of all the articles he wrote for Fiji Sun for twenty years:

"He [Fiji Government] who pays the piper [Fiji Sun] calls the tune"

"In 1999, on the eve of the general elections, I had written a long legal tract, suggesting why the self-appointed Major-General and Prime Minister of Fiji Rabuka should be stripped of his immunity and put on trial for the human rights abuses in Fiji. We have yet to recover from that debris, which also saw his clumsy imitator George Speight trying to wreak further havoc on Indo-Fijians because ‘they smelled differently’ in Fiji."

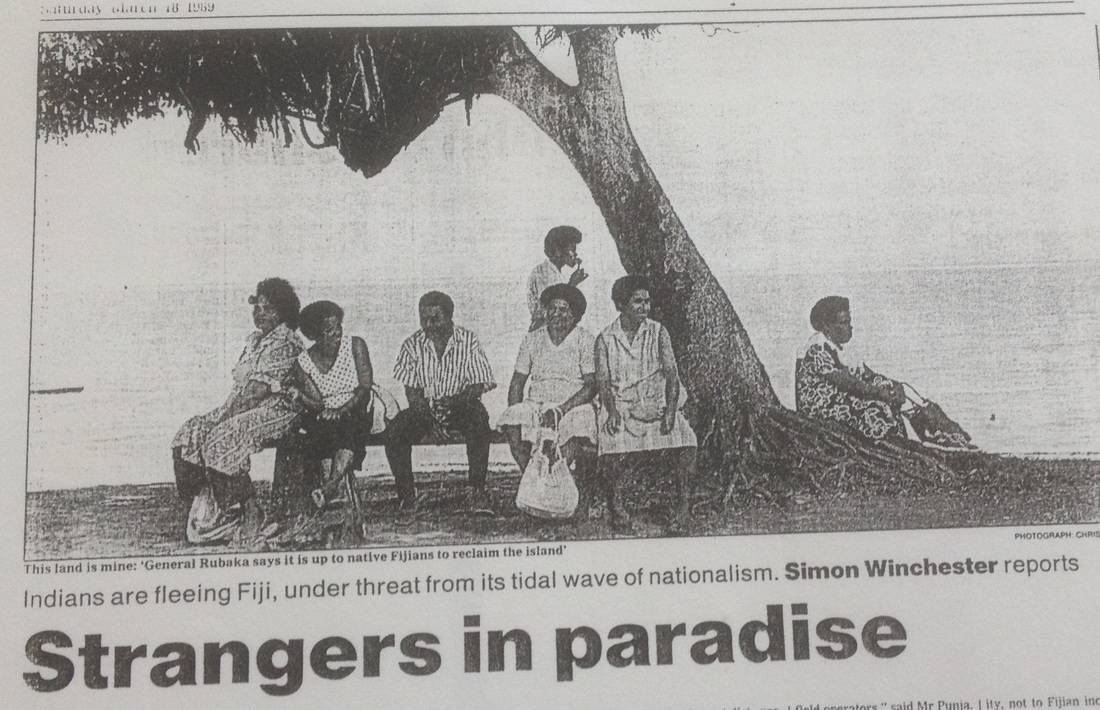

His Indo-Fijian and Fijian victims wait with trepidation for news of his US posting

By VICTOR LAL

Fiji Sun, 2005

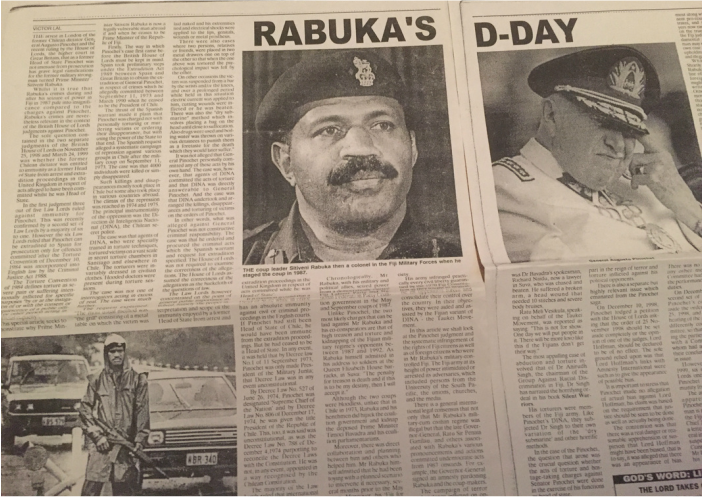

While the Father of the Two Coups in Fiji, Major-General Sitiveni Ligamamada Rabuka, has publicly expressed his unwillingness to accept his new diplomatic posting to Washington until his name is cleared as a suspect in the failed 2000 putsch, his former counterpart, the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet has had his immunity from prosecution stripped on 26 August by Chile’s Supreme Court, paving the way for possible trial of the dictator on charges of human rights abuses. The court voted 9-8 to lift the immunity the 88-year-old Pinochet enjoys as a former president, who came to power through the barrel of a gun.

The Chilean Supreme Court decision removes a major legal hurdle for prosecutors seeking to bring Pinochet to justice, adding to his legal woes after Chilean investigators recently opened a probe into multi-million dollar bank accounts in the United States, following the release of a US Senate report in July. The ruling came in a lawsuit brought on behalf of victims of ‘Operation Condor’, which they say was a coordinated plan of repression against opponents by the military dictatorships that ruled South American nation in the 1970s and 80s. Lorena Pizarro, who heads an association for relatives of victims of repression under Pinochet's dictatorship, said prosecutors now had to move quickly to bring him to trial. ‘Pinochet has to be tried!’ she said. ‘He must pay for all the crimes for which he is responsible. This has to be the window of opportunity bring to human rights violators to justice.’

General Pinochet seized power in a bloody 1973 coup that toppled elected leftist President Salvador Allende, who allegedly committed suicide in his presidential palace in flames, after it had come under attack. The dictator ruled until 1990, and was a regular visitor to London until the House of Lords ruled in 1998 that he could be stripped of his diplomatic immunity under international law and be put on trial for human rights abuses.

In 1999, on the eve of the general elections, I had written a long legal tract, suggesting why the self-appointed Major-General and Prime Minister of Fiji Rabuka should be stripped of his immunity and put on trial for the human rights abuses in Fiji. We have yet to recover from that debris, which also saw his clumsy imitator George Speight trying to wreak further havoc on Indo-Fijians because ‘they smelled differently’ in Fiji.

What an irony, some of his victims would say a travesty of justice and double standard, on the part of the United States of America, if Rabuka, is allowed to become our next Ambassador in Washington. But the ball is in democratic America’s court. Meanwhile, Rabuka might have the necessary qualifications and skills of a diplomat and has ‘discovered God’ but let’s examine his alternative CV for the prestigious post.

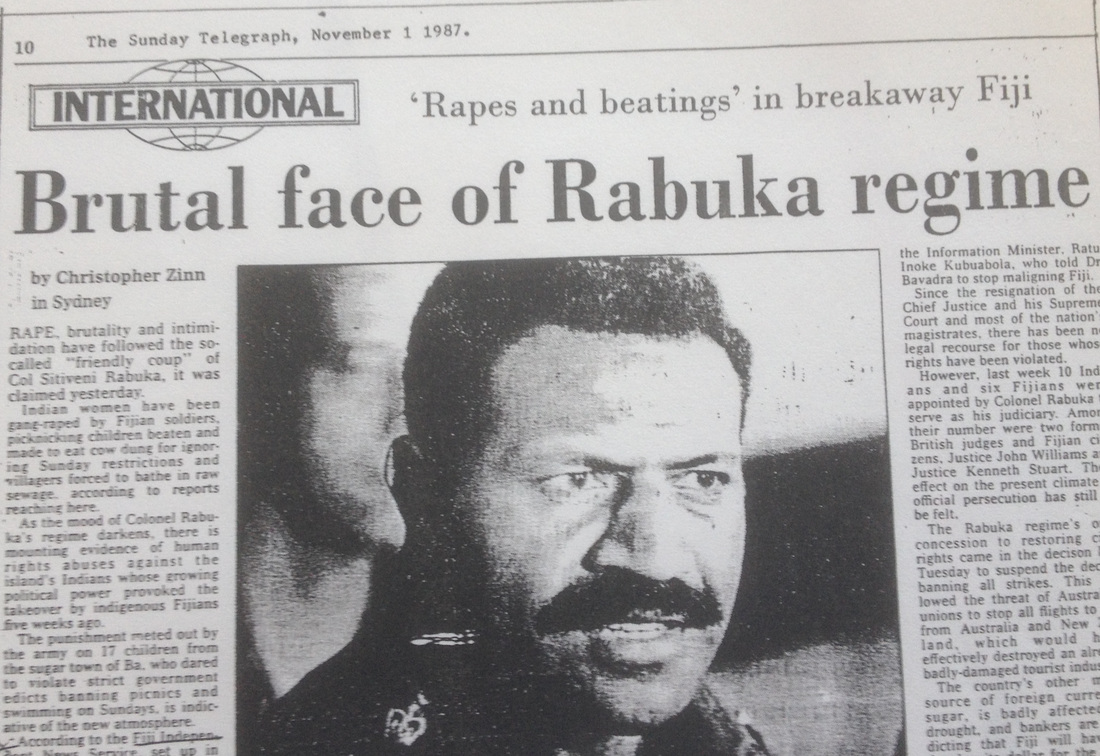

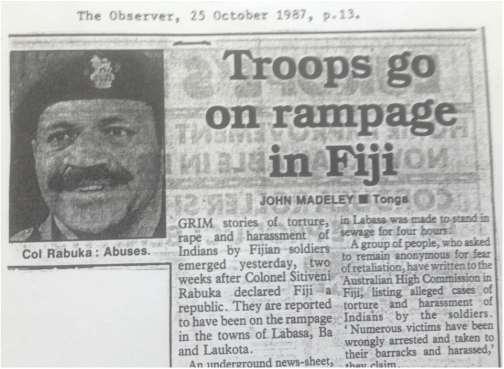

His record of human right abuses is well documented, and fulfilled the warnings of the late Prime Minister Dr Timoci Bavadra, who had warned the Commonwealth meeting in Vancouver, Canada in 1987 that, ‘It will be a time of oppression, a time of isolation and a time of severe economic deprivations’. True to Bavadra’s predictions, grim stories of the torture, rape, and harassment of Indo-Fijians emerged, later corroborated by Amnesty International. According to reports, the Indo-Fijians were beaten, forced to stand in sewage pools and subjected to other forms of humiliating treatment. A ban was imposed on any form of entertainment, coupled with the imposition of strict Methodist sabbatarianism on Fiji’s Hindus and Muslims, whom the Methodist lay preacher considered religious pagans. The long anticipated Day of Judgment had finally arrived for the Indo-Fijians. Thousands fled abroad, many to the United States, where their former tormentor and oppressor might be heading for the prestigious diplomatic posting.

Dictator Pinochet recently claimed that he was ‘an angel’ and that the abuses were carried out by his sub-ordinates. The courts have refused to accept his defence. Were the human rights abuses against Indo-Fijians and some Fijians operating in a vacuum, and without the knowledge of the military strongman Rabuka?

The dark days of Rabukism – US Court judgement

What transpired during the dark days of Rabukism in Fiji can be no better explained than by recalling an obscure and unreported judgement of the US Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit in San Francisco between an indigenous Fijian soldier, Aminisitai Tagaga, v the Board of Immigrations Appeal (BIA) and the US Justice Department (Case Number 98-71251), delivered in September 2000. The judgment was delivered by Justice Stephen Reinhardt.

The US Court of Appeals had granted a petition for review of an order of the (BIA). The court held that an alien may qualify for refugee status after deserting homeland military forces that required his participation in race-based persecution of fellow citizens. The Court heard that while a career officer in the Fijian Army, petitioner Aminisitai Tagaga was court-martialed for his resistance to an official policy of persecution of ethnic Indians.

Although he was an ethnic Fijian, Tagaga believed that Indo-Fijians deserved to be treated equally and have the same rights as others living in Fiji. He had refused to participate in the race-based arrest and detention of Indo-Fijians, and warned others of impending arrests. The military court revoked Tagaga's privileges, sentenced him to house arrest, and transferred him to Lebanon to serve with peacekeeping forces there. Tagaga learned from other high-ranking officers that his reassignment was punishment for his political opposition to the military regime in Fiji, and that he faced arrest and treason charges if he returned home.

After gathering his family Tagaga fled to the United States and applied for asylum. An asylum officer denied Tagaga's application. An immigration judge (IJ) was unswayed by evidence that Tagaga's life and freedom would be in danger if he returned to Fiji. The IJ concluded that Tagaga had failed to establish a well founded fear of persecution and upheld the asylum officer's decision. The BIA affirmed. Tagaga petitioned for review. To establish eligibility for asylum, an applicant must prove that he is unable or unwilling to return to his home country because of a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. A well-founded fear of persecution may be established by proving either past persecution or a good reason to fear future persecution. Justice Reinhardt ruled that a reasonable fact finder would have been compelled to conclude that Tagaga had a well-founded fear of persecution, and that he met the higher burden for withholding of deportation. Tagaga established a substantial likelihood that he would be tried for treason if he returned to Fiji. His fear was based on direct reports from high-ranking Fijian military officials.

The facts also established, Justice Reinhardt ruled that, having already served a sentence imposed by the military regime, Tagaga fled Fiji because he feared that the regime would prosecute him for treason for, among other reasons, his refusal to participate in the persecution of Indo-Fijians. Furthermore, a government may not legitimately punish an official for refusing to carry out an inhumane order. Had Tagaga followed orders and participated in the persecution of Indo-Fijians, he would have been ineligible for asylum. Tagaga, according to Justice Reinhardt, adhered to higher principles of law by refusing to arrest Indo-Fijians and warning others of planned arrests. For this, his confinement was excessive because it was unlawful.

An alien may qualify for refugee status after either desertion or draft evasion if he or she can show that military service would have required the alien to engage in acts contrary to the basic rules of human conduct. Hence, Justice Reinhardt ruled: ‘Tagaga's unwillingness to participate in the race-based arrest and detention of Indo-Fijians met that standard. Any reasonable fact finder would have been compelled to conclude that a future court martial of Tagaga by the military regime in Fiji would have been motivated at least in part by his refusal to participate in the persecution of Indo-Fijians. His well-founded fear of persecution and then likelihood that it would eventuate were he returned to Fiji were based on his political opinions and activities.

Justice Reinhardt overturned the initial ruling and granted Tagaga the stay of deportation order. He recalled the U.S. Department of State’s, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1993 635 (1994), which stated that ‘the purpose of the 1987 military coups was to ensure the political supremacy of the indigenous Fijian people’. The judge also dismissed the argument of the BIA which had referred in its opinion to general changes that had occurred in Fiji since the 1992 elections. ‘The record does not contain any evidence of improved country conditions directly relevant to Tagaga's case', Justice Reinhardt said.

The US Circuit Court had heard that Tagaga was an ethnic Fijian. ‘As a career military officer, he had earned the rank of major and held a high-level position in the Army's engineering corps. Through his work Tagaga established strong ties with the Indian community of Fiji, and beginning in 1985 he became an active supporter of the Indian-dominated Labour Party. He frequently attended Labour Party meetings and eventually became responsible for providing security at these meetings. Tagaga believed strongly that Indo-Fijians deserved to be treated equally and have the same legal rights as others living in Fiji. Following the first coup in May 1987, military personnel were ordered to cease contact with the Indian community. Tagaga did not do so. As he testified at the asylum hearing: ‘My relationship with the Indian community was too strong to have the ties broken.’ ‘

‘He continued to attend Labour Party meetings, even though he knew that undercover military intelligence agents also attended and had identified him. Military personnel warned Tagaga that if he did not discontinue his relations with the Indian community, he would face arrest and court-martial. By the time of the second coup in 1987, Tagaga began to refuse orders from his superiors directing him to arrest and detain Indo-Fijians whom the military regime perceived as threats to its power. Tagaga ‘didn't want to see the Indian population suffer anymore.’ He even gave information to the Indian community regarding future planned arrests. ’

On September 7, 1987, Tagaga was summoned to appear before a military court, and two weeks later he was prosecuted for disobedience of military orders, breach of discipline, insubordination, and conduct unbecoming an officer. At the court martial, Tagaga expressed his political opinion that the coup was illegitimate and that the government should be democratic. The military court revoked his military privileges and sentenced him to six months house arrest.

In February 1988 Tagaga was ostensibly reinstated as a major, but denied privileges and authority commensurate with that rank. In July 1989 he was transferred to serve in the Fijian division of the United Nations peacekeeping forces in Lebanon. Tagaga believed that military officials transferred him in order to separate him from the Indian community in Fiji and also to punish him by separating him from his family and subjecting him to the division's notoriously poor living conditions. In June 1990 a lieutenant colonel and close friend of Tagaga arrived in Lebanon.

He informed Tagaga that military officials had in fact sent Tagaga to Lebanon for the purposesof separation and punishment; that he remained under constant surveillance; and that he would face arrest and treason charges if he returned to Fiji. This lieutenant colonel, Tagaga's commanding officer, advised him to leave the army and not return to Fiji. A second lieutenant colonel confirmed this information for Tagaga. Tagaga decided to seek asylum in the United States. He went to the American Embassy in Israel and obtained visas for himself and his family.6 He returned to Fiji without reporting to military headquarters, gathered his family, and fled to the United States. He entered this country in September 1990 under a visitor's visa that authorized him to stay until September 6, 1991.

Six months prior to the expiration of his visa, he filed an application for asylum.

In his 2000 judgment, Justice Reinhardt ruled that, ‘The record is undisputed that Tagaga did not abandon his successful military career and flee his homeland because he was tired of the work or wanted a change in lifestyle. Rather, the uncontroverted facts establish that Tagaga, having already served a six-month sentence imposed by the military regime, fled Fiji because he feared that the regime would prosecute him for treason for, among other reasons, his refusal to participate in the regime's persecution of Indo-Fijians’.

Justice Reinhardt also pointed out the events of 2000, when Rabuka’s clumsy imitator George Speight tried to follow in Rabuka’s footstep.

It is true that Rabuka secured for himself a presidential pardon for his treasonous acts. But 1987 was not the first time Rabuka had planned to commit treason.

He has disclosed that in 1977 he had contemplated a coup if the National Federation Party had been allowed to form government after defeating Ratu Mara’s Alliance Party in the general elections.

He has however strongly protested his innocence regarding Speight’s putsch.

We can only imagine the fear and trepidation of Tagaga and hundreds of other Indo-Fijians who fled Rabuka’s racist Fiji.

On the other hand, if I were Rabuka, I would think twice before arriving in the US on a diplomatic passport.

For America is, after all, the greatest litigious society on earth.

And his victims and their lawyers are well armed with the massive dossier containing his reign of terror and human right abuses in Fiji.

The ghost of Pinochet will hover over Rabuka’s shoulder in Washington.

He can not escape the burden of history .