STANDING UP FOR 'IMMIGRANT RIGHTS'

In search of ancestral heritage in Fiji - Who is an 'Indigenous' Fijian?

By VICTOR LAL

Fiji's Daily Post, 2000; during George Speight's failed coup:

The present crisis in Fiji has once again raised the ugly spectre of a civil war in Fiji between native Fijians and Indo-Fijians. It is, therefore legitimate to ask: who is an indigenous Fijian? How many centuries will it take for the so-called 'immigrant' races in Fiji (the Indo-Fijians, Chinese, and Europeans) to become natives?

Fiji -Three-Legged Stool

The great Fijian leader Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna described Fiji as a Three-Legged Stool comprising Fijians, Europeans and Indo-Fijians (not to forget the Chinese and Rotumans). According to official Fiji government publication (Fiji Today, 1998), the Fijians are descendants of the great chief Lutunasobasoba, who led his people across the seas to the new land of Fiji. They landed in a great canoe, the Kaunitoni, on the west coast of Viti Levu, at a place which is now called Vuda, and they travelled inland in search of lands to settle until they reached the mountains of Nakauvadra. There they built a house for the old chief, who died shortly afterwards entreating his children from his dying couch to go forth and populate the land. This they did and many of the tribes of Fiji today trace their descent from the children of Lutunasobasoba. Most authorities agree that people came into the Pacific from Southeast Asia via Indonesia. Here the Melanesians and the Polynesians mixed to create a highly developed society long before the arrival of the Europeans.

The European discoveries of the Fiji group were accidental. The first Europeans to land and live among the Fijians were shipwrecked sailors and runaway convicts from the Australian penal settlements. Sandalwood traders and missionaries came by the mid 19th Century.

From 1879 to 1916 Indo-Fijians were introduced as indentured labourers to work on the sugar plantations. Their history, however, will record that their own displacement from British India prevented the dispossession of the Fijians in colonial Fiji.

Indeed, by a happy irony, the indentured Indian was uprooted specifically to prevent the Fijian way of life from disintegrating. The above official history of the Fiji Islanders (as everyone is known now) thus shows that we are all former migrants to the Fiji islands. It is in this context that we can ask the question: who is indigenous?

Definition of Indigenous Peoples and Related Terms

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention 107 (1957); Article 1 provides that the Convention applies to:

(a) members of tribal or semi-tribal populations in independent countries whose social and economic conditions are at a less advanced stage than the stage reached by the other sections of the national community, and whose status is regulated wholly or partially by their own customs or traditions or by special laws or regulations;

(b) members of tribal or semi-tribal populations in independent countries which are registered as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or consolation and which, irrespective of their legal status, live more in conformity with the social, economic and cultural institutions of that time than with the institutions of the nation to which they belong. Furthermore, ILO's Convention 169 (1989);

Article 1(1) stipulates that the Convention applies to

(a) tribal peoples in independent countries whose social, cultural and economic conditions distinguish them from other sections of the national community, and whose status is regulated wholly or partially by their own customs or traditions or by special laws or regulations;

(b) peoples in independent countries who are regarded as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or colonisation or the establishment of present state boundaries and who, irrespective of their legal status, retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions.

The World Bank policy on indigenous peoples are as follows: 'Tribal peoples are ethnic groups typically with stable, low-energy, sustained yield economic systems, as exemplified by hunter gatherers, shifting or semi-permanent farmers, herders, or fishermen.' They exhibit in varying degree many of the following characteristics:

(a) geographically isolated or semi-isolated;

(b) unacculturated or only partly acculturated into norms of the dominant society

(c) non-monetized, or only partly monetized; production largely for subsistence, and independent of the national economic system;

(d) ethnically distinct from the national society;

(e) non-literate and without a written language;

(f) linguistically distinct from the wider society;

(g) identifying closely with one particular territory;

(h) having an economic lifestyle largely dependent on the specific natural environment;

(i) possessing indigenous political leadership, but little or no national representation, and few, if any, political rights as individuals or collectively, partly because they do not participate in the political process; and

(j) having loose tenure over their traditional lands, which for the most part is not accepted by the dominant society nor accommodated by its courts; and having weak enforcement capabilities against encroachers, even when tribal areas have been delineated.

It is thus clear that the Fijians do not, by any stretch of the imagination, fall into such categories. Although a minority for several decades, the Fijians never suffered the effects of dispossession, discrimination and political marginalization. In fact, it was the Fijian chiefly leaders who enjoyed sustained political control of the country since independence, and still communally own 83% of the land (now a weapon of political blackmail), dominate the Fiji army, and the Great Council of Chiefs' nominees in the Senate have a veto over any Bill affecting Fijian land, custom or tradition.

The entrenched land rights makes it impossible for any dispossession to take place without the consent of the chiefs. It is, therefore, absurd to liken the position of Fijians today to that of the Aztecs, the Incas, the Mayans and the Aborigines.

Minorities in International Law

The 1990 post-coup Constitution-makers had invoked the doctrine of indigenous supremacy to enable Fijians to enjoy more rights than other races and to institute a new system of domination and inequality.

The central idea of the ILO conventions however was to institute an order that guaranteed equally fundamental rights including equality of franchise. In fact, if any group(s) which might have a legal claim in international law are the minority communities (Indo-Fijians, Chinese, Europeans and Others in Fiji).

It is they, the international lawyers could claim, who need constitutional and political safeguards for the possible violation of their rights under various international legal conventions, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that all persons are 'equal in dignity and rights' and that this should not be abridged on the basis of 'race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, or other status (article 2).

These prohibitions are repeated in several other conventions including Articles 2, 3 and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Article 3 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and Article 5 of the International Convention for the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination.

Fiji is a signatory to these various conventions. As a matter of fact, whenever the question of constitutional reform had been considered during British rule, the Fijian leaders based their claim not as indigenous peoples but as a minority fighting to maintain a separate identity. In the process, the Indo-Fijian bourgeoise leaders went along with their Fijian counterparts, totally oblivious to future population trends which led to Indo-Fijians becoming a minority in Fiji.

In short, if there were any losers in the long, tortuous, and complex struggle for political power in the 1970s, it was not the pettit-bourgeois Indo-Fijian leaders but the ordinary descendants of indentured Indo-Fijians. The so-called 'Passenger Indians' remained unscathed in economic terms Thereafter, what Fiji witnessed for the next two decades, was the politics of race until the rise, demise, and rise of the multi-racial Fiji Labour Party in 1987 and 1999.

What Fiji is witnessing in the formation of the Foundation of the Fijian Indigenous Peoples, threats of repatriation of Indo-Fijians and 'blood will flow' in the wake of ALTA debates, and the exclusion of the Prime Minister from the Great Council of Chiefs, is an attempt by a mindless minority to revert back to the era of racial bigotry and racial politics in Fiji.

Moreover, what some Fijians believe to be their ancient heritage is a colonial legacy. Like the deep cleavages existing within the Indo-Fijian community, pre-colonial Fijian society consisted of a series of tribes and tribal confederacies that were frequently in conflict with each other. Tribes in eastern Fiji were heavily influenced by Polynesians from Tonga, and developed a very hierarchical Polynesian-style social structure with great power in the hands of hereditary chiefs.

The social structure of western Fijian tribes was more egalitarian, as is the Melanesian custom. In 1874 Britain accepted the cession of authority in Fiji to the British Crown by the eastern chiefs. The new colonial authorities succeeded in bringing all Fijians under the control of a single government for the first time. The British largely ruled through the existing chiefs, greatly enhancing chiefly authority over Fijian commoners. They also established the dialect and traditions of one eastern tribe as the norm for the entire country.

A rather romantic view of traditional Fijian society prevailed, and laws were passed to reinforce communal land ownership.

The Indigenous/Immigrant Debate

In 1976 the current president Ratu Mara, then prime minister, while rejecting a suggestion in the Senate by Senator Inoke Tabua, later a leading Taukei member, that 100,000 Indo-Fijians should be deported, made a pertinent statement: 'It is now being suggested that there are sections of citizens of Fiji, particularly the Indians, who have not the same rights as any others. I do not see that. If I made a mistake at the Conference (1970), please do not support me at this forthcoming election (1977). I would rather square my conscience with God then to be voted back into Parliament under false pretences. If you start removing Indians, the next ones will be the Chinese, the third ones will be the Europeans, and the fourth will be the Lauans.'

The Lauans, who are descendants of Tongans, settled in Fiji in the 19th century with their chief Ma'afu, a relative of the King of Tonga. Ma'afu, who settled in Fiji in 1848, thirty-one years before the arrival of the first batch of Indo-Fijians to Fiji, established himself at Lakeba as the leader of the Tongan community in Fiji. According to the historian Peter France, the Tui Nayau, who controlled the Lau islands from Cicia in the north to Ono in the south, was at this time an old man, corpulent, and severely afflicted by elephantiasis. With his company of Tongan fighting men, Ma'afu became military representative of Tui Nayau and extended his authority by conquering, in the name of Christianity, the islands of the Moala group; these were thenceforth accepted as being part of Lau.

The islands north of Cicia owed allegiance to Tui Cakau but, when this chief visited Lakeba in 1850, he accepted a canoe as a gift from Ma'afu and gave him, in return, rights of levy over them. In 1855 Ma'afu put down a religious war in Vanuabalavu and assumed control over the island, taking up residence at Lomaloma. His position in Fiji at this time was that of representative of King George of Tonga, the head of the Tongan community in Fiji, and the owner of the island of Vanuabalavu. He extended his influence throughout Vanua Levu by alliance with Tui Cakau and Tui Bua. He then defeated Ritova, Tui Macuata, and installed a chief more susceptible to his influence as head of the chiefdom.

Ma'afu was the most powerful influence in north-eastern Fiji when, in 1859, the first cession proposal was made. Consul Pritchard reminded Ma'afu that, as the country had been ceded to England, future attempts to extend his authority would bring him into conflict, not with mere Fijian chiefs, but with the British Government. Ma'afu signed a document to the effect that he was in Fiji solely to manage and control Tongans and had no claim to chiefly authority over Fijians.

After the first offer of cession was rejected, however, he resumed his attempts to secure a position of leadership and, in 1867, he appeared to have succeeded in uniting the provinces of Vanua Levu and Lau by creating the Tovata. On the collapse of this confederation he declared that he would have no further dealings with Fijian chiefs and retired to his estates on Vanuabalavu. Tui Nayau raised the Tongan flag at Lakeba and Ma'afu began to assume control over the Lau group, under the excuse that its chief had declared it to be Tongan, and not Fijian, territory.

In June 1868, however, the Tongan Parliament ordered the flag to be hauled down and instructed Ma'afu to cease from involving the Tongan Government in Fijian affairs. This meant that he could not continue to exercise control by virtue of his authority as a Tongan chief, but had to be accepted as a chief in Fiji. A meeting of the chiefs of Lau was held at Lakeba, in February 1869, at which he was installed as a Fijian chief, taking the title of Tui Lau (now held by Ratu Mara); his connection with the Tongan government was severed; a vessel was sent to Fiji from Tonga, proclaiming that Tongans who remained in Fiji would no longer be under the protection of the Tongan Government and offering passages to those who wished to return. Tongan lands in Fiji were made over to Ma'afu and he was accepted by the chiefs of Bua and Cakaudrove, in May 1869, as a chief of Fiji, having authority over Fijians. He played a leading part in the offer of Cession in 1874.

Some radical Fijians therefore assert that because of his family background, Ratu Mara does not have the automatic right to champion Fijian rights.. As a matter of fact, the case of Lauans is instructive to our indigenous/immigrant debate. In 1987 Ratu Mara, unlike a decade ago, began to assert paramounty rights on behalf of the Fijians in the new post-coup Constitution, saying that 'special rights for indigenous peoples are not something new and are provided for under international law'.

He reminded his critics of the fate of other indigenous peoples saying that 'the Fijian people are all too aware of the destiny of the indigenous Aztecs of Mexico, the Incas of Peru, the Mayas of Central America, the Caribs of Trinidad, the Amerindians of Guyana, the Maoris of New Zealand, and the Aborigines of Australia'. From these arguments, Ratu Mara concluded that Fijians must be awarded majority representation in Parliament and control of the government as 'an affirmative action to guarantee and protect the rights and aspirations of the Fijian people against other communities'.

He argued that Fijians had settled in the islands over 3,500 years ago, and this fact entitled them to paramount control of Fiji. He, however, did not explain or justify why his predecessor, Ma'afu as Tui Lau, could lay claim to Fijian paramounty and Indo-Fijians not for equality, when he (Ma'afu) had been in Fiji for 26 years only before the Deed of Cession of 1874, and not 3,500 years.

The Tui Bua, Vakawaletabua, also had personal links with Tonga: his mother was Tongan and he had been placed in peaceful occupation of his chiefdom of Bua by Tongan force of arms. In 1862, he visited Tonga, with Ma'afu. A Treaty of Friendship between King George of Tonga and Tui Bua was signed on 3 January 1865. This provided for perpetual peace between Tonga and Bua and for reciprocal rights of settlement. It also provided that the Civil Service of each state would make available its employment opportunities to the nationals of the other: any Tongan settling in Bua was declared to be eligible 'for appointment to any Government situation that may be vacant', with the same privilege applying to a Buan settling in Tonga.

It is therefore not surprising that Jone Dakuvula, a cousin and former press secretary to Sitiveni Rabuka, had also asked during the two coups in 1987: 'What is so special about us descendants of the many waves of early settler groups in Fiji that our political rights to be the government must be greater and secured unaccountably, compared to the descendants of later settlers?' Dakuvula further argued that the people did not want an apartheid-type regime because the Indo-Fijians were no longer foreigners, but part of the Fijian polity. Why should they accept diminution of their political rights in their own country; the country of their birth?.

The current prime minister Chaudhry had also stated his position: 'We have a fight on our hands and I believe in dealing with it until the matter is resolved one way or the other. I was born here. I am not a foreigner here. I have every right to fight for this country. We are not going to subjugate ourselves to a constitution of this kind (the 1990 Constitution), signing away all our rights and agreeing to be slaves.' In a cruel twist of fate, he went on to become the first prime minister of Indo-Fijian origin.

Perhaps the speech of Ratu Sukuna to the Great Council of Chiefs in 1936 is worth repeating: 'Let us not ignore the fact that there is another community settled here in our midst. I refer to the Indians. They have increased more rapidly than we. They have become producers on our soil. They are continuously striving to better themselves. Although they are a different race, yet we are each a unit in the British Empire. They have shouldered many burdens that have helped Fiji onward. We have derived much money from them by way of rents. A large proportion of our prosperity is derived from their labour.'

A central figure in the 1987 Fiji coups has defended the island nation's Indo-Fijian population as fully fledged Pacific Islanders. More recently, Ratu Mara criticised an international Pacific Island conference held in Auckland for excluding Indo-Fijians. Ratu Mara, the keynote speaker at Pacific Vision, a four-day conference, said that, "This is a conference of the Pacific communities in New Zealand, yet the Pacific Vision literature I have read appears to have an omission. There is no reference that I could see to the Indians from Fiji. Fiji Indians are full citizens. They are officially designated as Fiji islanders and one, the Honourable Mahendra Chaudhry, is now prime minister. They may have a distinct and different appearance and characteristics and been late arrivals, but islanders they are."

The Fijians and Non-Fijians: 'Marooned at Home'

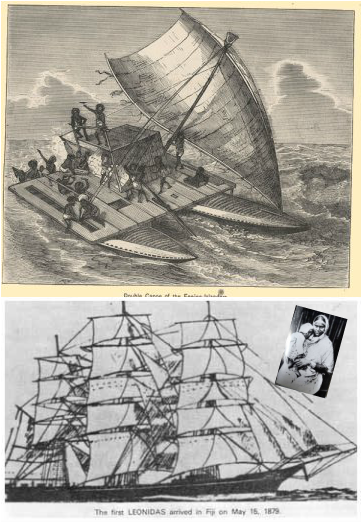

On 14 May 1987, the Indo-Fijians awoke to mark the 108th anniversary of the arrival, aboard the sailing ship Leonidas, of the first Indo-Fijian 'coolies' in Fijian waters. In fact, that day was to see the arrest of all their progress- from plantation to parliament- when Sitiveni Rabuka and his henchmen overthrew the multi-racial Labour government. The Fijian coup d'etat also raised the fundamental question: how many generation should the Indo-Fijian community (and other non-Fijian races) wait to become 'natives'?.

We have already recalled the Tongan Parliament's reaction to Ma'afu's status in Fiji. The following declaration of the late Prime Minister of India, Jawarharlal Nehru, has a similar echo. He raised the issue of citizenship, including that of the Indo-Fijians, in the Indian Parliament on 8 March 1948: 'Now these Indians abroad? Are they Indian citizens or not? If not, then our interest in them becomes cultural and humanitarian, not political. Take the Indians of Fiji and Mauritius: are they going to retain their nationality, or will they become Fiji nationals or Mauritians? Of course, the two things do not go together. Either they get the franchise as nationals of other country, or treat them as Indians minus the franchise and ask for them the most favourable treatment.'

The following declaration of an ex-indentured woman labourer Rangamma, in 1979, who arrived in Fiji with her parents a century ago, in 1899, still applies to the Indo-Fijians today: 'Fiji is my place. There is nobody in India for me.'

It is equally true of the descendants of the great chief Lutunasobsoba, who cannot be expected to return 'home' from the coast of Vuda and the mountains of Nakauvadra, to a land far to the west in the great canoe, the Kaunitoni. Or the small but significant Fiji-born Chinese community to mainland China. As we gear up to greet the dawn of a new century, we have reached that tide in the affairs of men

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

It is to be sincerely hoped that we will collectively judge each other not on the basis of our colour or ancestry but by the content of our character.

The coup leader George Speight has certainly failed the test of character and some have even expressed doubt about his "indigenous" colour. He alone has the chance to redeem himself from his mindless act.

Fiji, says the tourist poster, is 'the way the rest of the world should be'.

Let us keep it that way in the 21st Century.

Fijileaks Editor: That was in 2000, now listen to Niko Nawaikula who explains the anti-indigenous decrees passed since the 2006 coup.