For Your Diary:

Fijileaks will not be updated between 25 August and 4 September

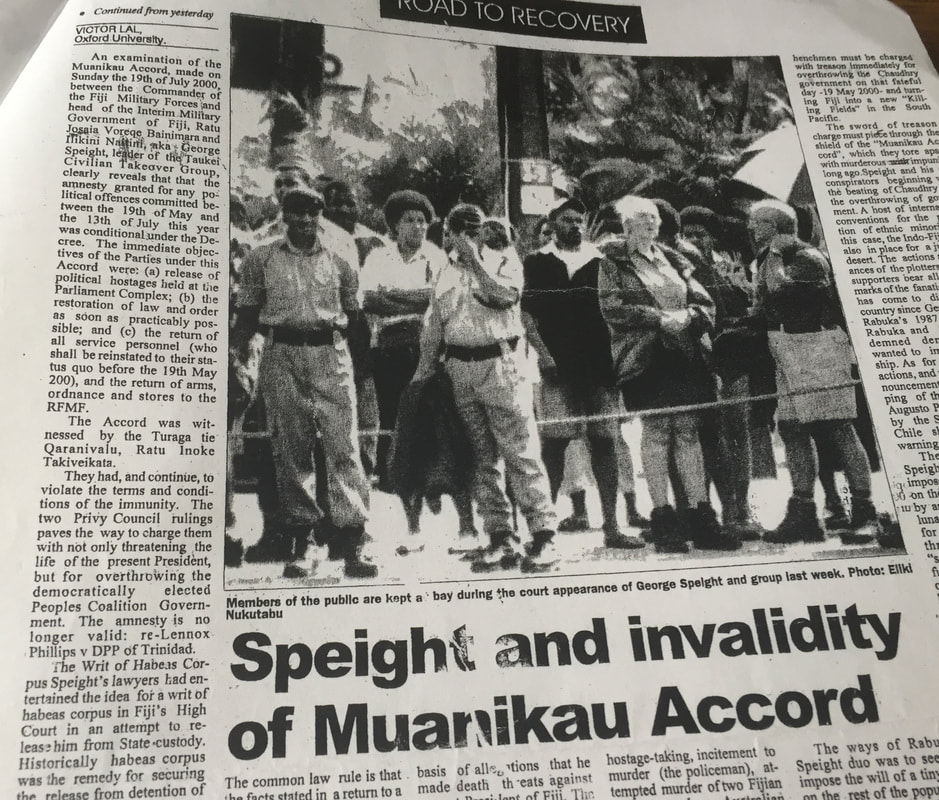

Fijileaks: In 2000, our founding Editor-in-Chief VICTOR LAL had written a series of ten articles in Fiji's Daily Post, explaining why Chaudhry fell from power. Chaudhry agreed with the general analysis, except for what he termed 'a few incorrect assumptions'. We will chart FLP leader Mahendra Chaudhry's journey from 'political saint' to 'currency convict', arising from the debris of George Speight's failed coup of 2000. Ironically, Lal's political columns in the Fiji Sun came to an abrupt end when he exposed Chaudhry's secret $2million in his (Chaudhry's) Australian bank account. Following the abduction and deportation of Fiji Sun publisher Russell Hunter in 2008, the new management at the Fiji Sun discontinued Lal's opinion column, resulting in the founding of Fijileaks. Victor Lal will resume his Opinion Column closer to the general election.

Meanwhile, we continue with PART TWO from Fiji's Daily Post:

The Fatal Embrace:

The FLP and Chaudhry’s Road to Ruin

Part Two

The Fatal Embrace:

The FLP and Chaudhry’s Road to Ruin

But in the May general elections the party made a fatal political mistake by embracing the splinter Fijian political parties into its fold to form a Peoples Coalition during the run-up to the elections. We have already dealt with the VLP. Whoever was advising Chaudhry and the FLP had not immersed himself/herself into the impetuous character of Fijian history and politics. Like his political foes in the NFP (Notoriously Faction-Ridden Politicians), the Fijians in the Peoples Coalition had convinced themselves that it was only in the company of FLP that they could find new jobs as Ministers and Backbenchers. Some Fijian politicians were merely using the coalition with the FLP to achieve their dreams of becoming Prime Minister of Fiji after the May elections.

Having demolished the once invincible and faction-ridden NFP, as well as the chiefly sponsored and Rabuka led SVT, Chaudhry however found himself chained to a new 1997 Constitution with its mandatory provision for power sharing, entitling any political party with more than 10 per cent of the seats in the Lower House to a place in Cabinet (in proportion to its percentage of seats). The party with the most number of seats provided the Prime Minister, who allocated portfolios in Cabinet. Because of this provision for a multi-racial cabinet, the parties in the Peoples Coalition formed only a loose coalition among themselves, leaving the details of power sharing and leadership to be decided after the elections. More importantly, the politics of race was, for once, relegated to the background because both the coalitions, the Peoples Coalition and the SVT/NFP/GVP Coalition were multi-racial in character, at least for electoral purposes.

Chaudhry charms and alarms Taukeis

It is no secret that disgruntled Fijian politicians under the guise of Taukeism played a leading role which set the stage for George Speight and his henchmen to overthrow the Chaudhry government. Land and race was mixed with politics, even though these sensitive issues were not on the voters minds. A Tebbutt Research on behalf the Fiji Times in April 1999 revealed that 26% of the voters thought unemployment was the most important issue in the election (Fijians 30% and Indo-Fijians 23%); followed by land issues/ALTA (14% - Fijians 8% and Indo-Fijians 21%). According to SVT official Jone Dakuvula, a SVT-inspired agitation and destabilisation against Chaudhry began almost immediately after Chaudhry’s win. Jim Ah Koy, who was Finance Minister in Sitiveni Rabuka’s last government, while distancing himself from Speight’s take-over of Parliament, said he understood the Speight’s groups frustration and anger. He blamed the Chaudhry government’s ‘arrogance and obduracy in not listening to the sensitivities of the indigenous Fijians’.

Chaudhry sought to introduce a Land Use Commission to restructure land ownership. On 3 April 2000, based on World Bank Report and other reputable sources, Chaudhry declared Fiji would remain poor as long as the land remained underdeveloped. That ‘development’ required larger plantations and more secure titles in order to attract investment. Chaudhry also offered small Indo-Fijian growers $28,000 each to leave their farms and proposed that leases be extended for 60 years at the current low rents. Both the Council of Chiefs and the NLTB opposed these measures, accusing Chaudhry of favouring the Indo-Fijian tenant farmers and undermining the Council of Chiefs. Ironically, as the plight of the Indo-Fijian farmers worsens, with frightening consequences for the econony in general, the Interim Administration has agreed to pay the displaced farmers $28,000 or less depending on their circumstances.

On the day of Speight’s coups, about 5,000 people marched through Suva, demanding Chaudhry’s removal, following a similar march on 28 April. Marchers denounced the Government’s planned changes to land use, accusing it of moving to ‘usurp land’ from native landowners. They also attacked Chaudhry for showing ‘disrespect’ for the Council of Chiefs. The marches were called by the Fijian chauvinist Taukei Movement and led by Apisai Tora, who lost his parliamentary seat in the general elections. Tora revived the Taukei, which also staged marches and carried out racial attacks on Indo-Fijian citizens and politicians as a prelude to the 1987 coups.

SVT secretary Jone Banuve gave his endorsement to Speight as he entered the besieged Parliament to meet him. He also issued a statement in the SVT’s name, saying: ‘We will never accept the reinstatement of the Chaudhry, nor any non-Taukei leadership’. The SVT’s parliamentary leader, Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, said he knew nothing about the statement. Whether or not Kubuabola, the principal architect of the 1987 coups, knew of the statement, most of the Fijian politicians and leaders were attempting to leverage favourable outcome. While Sitiveni Rabuka issued a statement saying there should be ‘no amnesty’ for Speight and his followers, his ambiguous position was summed up in comments to the media: ‘I sympathise with your [Speight’s] cause, but I don’t agree with your methods.’

Tora, like Rabuka, said he sympathised with the cause but did not approve of the methods. He said the Taukei Movement had its own plan which he says was a much more logical approach.

Chaudhry, on the other hand, had impressed and charmed even some of the die-hard Taukei members with his leadership qualities. Taukei activist Sivoki Mateinaniu said members of the Taukei Movement and Fijian politicians should learn from Chaudhry. ‘Mr Chaudhry’s policies are simple. He is just trying to implement what he promised; unlike the SVT government who forgot its election promises as soon as they were elected. Now the Fijians are still confused because our so-called leaders forgot to protect us in the [1997] Constitution. They did not even formulate legislation to protect our cause’, Mateinaniu said. ‘In the 1999 elections, they could not promise the Fijians anymore because they had failed to deliver in 1992 and 1994’. He called on Fijians not to listen to the hollow calls to disrupt stability and good governance. ‘The Taukei Movement now supports Mahendra Chauhdry’.

Emperor Without the Prime Ministerial Robe

It was a remarkable transformation on Mateinaniu’s part and an honest and accurate assessment of Chaudhry’s leadership qualities. As the veteran politician and political commentator Sir Vijay Singh observed that, ‘Of all the major political parties, Mahendra Pal Chaudhry alone retained a clear vision of his party’s constituency-workers and farmers, the poor, and the deprived’ of all the races in Fiji’. Furthermore, the FLP had an extensive network to communicate that message. The Fiji Public Service Association, of which Chaudhry was the head, reached out to the public sector. He was also able to galvanise the farming community through the National Farmers Union, of which he was the head.

The Labour candidate, Pratap Chand, as head of the Fiji Teachers Union, was able to reach out to primary and secondary teachers who play an educative role in our muti-racial community. For many Indo-Fijian voters, the NFP’s, and in particular its leader, Jai Ram Reddy’s, achievements on the promulgation of the 1997 Constitution and talk of racial harmony were abstract issues. Also, the coalition with Rabuka’s SVT was insignificant. As Sir Vijay put it, ‘in restoring the democratic constitution’, Rabuka ‘did the Indians no favour’. He ‘restored what he had stolen in the first place’. The FLP also promised policies and initiatives of its own: the removal of the 10% Value Added Tax (VAT) and Customs Duty from basic food and educational items, review taxation on savings and raise allowances for dependants, provide social security for the aged and destitute, and lower interest rates on housing loans.

The FLP had caught the peoples imagination. It was ‘Time for a Change’.

And it was indeed a refreshing political change of scene.

The voters of Fiji elected by a landslide the ‘Peoples Coalition’ consisting of the FLP, the Party of National Unity (PANU) and the Fijian Association Party (FAP), with Labour winning 37 of the 71 seats, enough to govern on its own. However, it was the beginning of the end of Chaudhry’s government. The root and arguably the most significant cause of the demise of the Chaudhry government was not the Taukei Movement marches, the puppeteer George Speight and his financiers or Chauhdry’s arrogance but (i) the provisions of 1997 Constitution of Fiji, and (ii) the non-Fiji Labour Party Fijian politicians in the ‘Peoples Coalition’.

At the end of the day, these Fijian politicians had entered the government not on the platform of multi-racialism but as representatives of the various fractious Fijian political parties. They had racial and communal outlooks both in history and their pronouncements.

The Constitution and the election results had left the other half of the Fijians to brood, sulk, make political, provincial and tribal alliances, and plot or if necessary, to club their way back to political power under the guise of indigenous rights. Chaudhry had inherited a ‘Divided House of Representatives’ and as a result his antagonists were able to run through and occupy it illegally. He became a ‘Fall Guy’. Race and not tribalism triumphed on that fateful day, 19th of May 2000. The failed coup was executed to effectively oust his Fijian Association Party (FAP) and other Fijian guests from the House, who should not have been invited as his honoured guests in the first place under the 1997 Constitution. Chaudhry-the King Maker-had overnight become an Emperor Without the Prime Ministerial Dhoti (Indian sarong).

The 1997 Constitution, with its provision for multiparty government, had made him both the victor and the vanquished. His political gurus also slavishly allowed him to be dictated by Ratu Mara in the formation of his new government. As we have already pointed out, Chaudhry was caught with his Indian night political dhoti down in the company of ‘liu muri’ Fijian political bedfellows. Pre and post-cession Fijian history was repeating itself.

The new Constitution had brought Fijian political quarrels to the Fiji Labour Party’s doorsteps. Chaudhry, the ‘misguided saint’, foolishly opened the political and multi-racial gate to his FLP-led government and in the process the ‘devils’ ignominiously and unceremoniously bundled him out of the political kingdom. ‘The King is Now Politically Dead but the Memory of Fijian Infighting Still Lives On’.

To be continued: The Fijian Seeds of Chaudhry’s Troubles and Downfall