The opinion polls about voting intentions for the 2022 Elections suggest that Fiji’s voters face the horrible challenge of choosing as their next Prime Minister one of two former military officers.

Both of these former soldiers have carried out military coups removing lawfully elected Governments.

Is Fiji genuinely between, as the saying goes, “a rock and a hard place”? I suggest that today’s young voters, who have only known 14 years of the governance by the Bainimarama Government, need to think also about how Mr Rabuka governed Fiji after his 1987 coup.

Both coup leaders may have coup skeletons in their cupboards.

But only one is being very selectively focused on by the current RFMF Commander, writing (appropriately) in Fiji’s other daily newspaper.

Fiji’s voters ought to focus on historical facts by answering the following difficult questions about the two coup leaders:

Behind the 1987 coup?

The world knows that Sitiveni Rabuka, the third in command in the RFMF, implemented the first 1987 coup.

But anyone watching the very public protests against the 1987 NFP/FLP Government would have known that the former Prime Minister (the late Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara) and the Governor-General and later President (the late Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau), and all their entourages would have had their ears very close to the ground and, possibly, their fingers in the pie.

But importantly, what did Mr Rabuka do afterwards as coup leader?

Rabuka became multiracial

Victor Lal and Fijileaks rightly remind readers about the trauma that Mr Rabuka’s 1987 coup caused the Indo-Fiji community.

But what needs also to be discussed is Mr Rabuka’s reform of the racist 1990 Constitution and his support of the revolutionary 1997 Constitution.

Mr Rabuka, in partnership with Jai Ram Reddy (Leader of the National Federation Party) agreed to the appointment of the three person Reeves Constitution Commission (Sir Paul Reeves, Tomasi Vakatora Senior and Dr Brij Lal).

Their report was the basis of the 1997 Constitution, with one valuable addition not in the Report.

It is sadly often forgotten today that the 1997 Constitution included a “multiparty government” provision.

This ensured that any party with at least 10 per cent of the seats in Parliament had to be invited to join the Cabinet and share in the governance of Fiji.

Of course, there was one huge defect in its electoral system which I had explained even as I (as a NFP Member of Parliament then) voted to pass the 1997 Constitution (“The Constitution Review Commission Report: sound principles but weak advice on electoral system”. The Fiji Times, November 1, 1996).

But we in the NFP were in a hurry to approve the progressive constitutional change agreed to by Mr Rabuka.

We knew he had to convince some very reluctant colleagues, and we fully co-operated for the 1999 Elections.

I remember accompanying Ratu Inoke Kubuabola in his election campaigns in the Yasawas and Ratu Sakiusa Makutu in Nadroga.

Sadly, both Indo-Fijian and indigenous Fijian voters rejected the multiracial stance of Mr Rabuka and Mr Reddy.

Nevertheless, it is to Mr Rabuka’s credit that he accepted the results of the election and humbly offered his services to Mahendra Chaudhry as the incoming PM (on the phone in my presence on the Vatuwaqa Golf Course).

Unfortunately, for reasons that historians can explore till the cows come home, Mr Chaudhry did not accept that humble offer from Mr Rabuka, who soon after lost the leadership of SVT to Ratu Inoke Kubuabola.

Ignored today are the following:

Behind the 2000 coup?

It is a real tragedy that while George Speight is seen as the leader of the 2000 coup, the truth has never been revealed about who else, including military officers, might have had more than just a sticky hand in it.

It is a real tragedy that Fiji has forgotten the names of a few honest RFMF officers who were very ethically opposed to the 2000 coup. From personal communications to me, I list the following: Ilaisa Kacisolomone, George Kadavulevu, Vilame Seruvakoula, Akuila Buadromo and several others.

But also conveniently forgotten are the names of RFMF officers who were at least initially behind the 2000 coup, many revealed by the Evans Board of Inquiry Report (which can be freely downloaded from the TruthForFiji website).

What is historically indisputable is that after RFMF gained control of the situation Mr Bainimarama chose not to restore the lawful Chaudhry Government to power but appointed the interim Qarase Government, thereby effecting the real coup.

It is said that some of the CRW soldiers involved in the November 2000 mutiny did so because they felt betrayed by some in the RFMF hierarchy.

It is not disputed that a number of CRW soldiers (not necessarily involved in the mutiny) ended up dead after the mutiny in circumstances not known to this day.

It is not in dispute that Mr Rabuka, with his uniform, appeared at Queen Elizabeth Barracks at the time of the mutiny.

But while one newspaper is focusing on his actions, the roles of several other senior RFMF officers during the 2000 coup are not being similarly examined.

2006 and governance since then

Now we come to the 2006 coup.

In contrast to those which went before, there is no doubt whatsoever that the then RFMF Commander Mr Bainimarama was the sole leader of the 2006 coup and totally controlled the Government thereafter, while still controlling the RFMF.

Given what have I sketched above, the sheer contrasts of the Bainimarama coup with the Rabuka coup are all too obvious.

It is tragically forgotten that the 2006 coup did not just depose Mr Qarase’s SDL Government.

It deposed a multi-party government – a government of Mr Qarase’s Soqosqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua (SDL) Party and FLP.

One can understand why Mr Chaudhry as FLP leader has never emphasized that point.

Soon after the 2006 coup he joined Bainimarama’s Government as Minister of Finance.

It is indisputable that Mr Bainimarama ruled Fiji for eight years as the head of a military government which was not democratically accountable to the Fiji public.

A “People’s Charter” exercise was carried out under the leadership of John Samy and the late Archbishop Mataca but rejected without explanation.

Professor Yash Ghai’s Constitutional Commission was appointed by Bainimarama and Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed- Khaiyum.

It produced a comprehensive draft constitution, but Professor Ghai and his Commission were also were sent packing for reasons never clarified.

A 2013 Constitution with little popular input was imposed on Fiji without the approval of any elected Parliament.

The Senate was abolished.

Parliament has become a rubber stamp for the legislative changes the current government wants.

Many important institutions of Government were allowed by the Constitution to come under the direct or indirect control of the politicians who controlled the Government.

Large sections of the media (with the painful exception of The Fiji Times) and the Media Industry Development Authority came under Government influence or control.

Undermining the Ministry of Information, a massive amount of money was spent annually on American propaganda machine Qorvis.

One Government Minister, not the Prime Minister, clearly became all powerful while others toed the line or were ejected from Parliament.

To fund the ruling party’s electioneering, the owners of some of Fiji’s largest businesses have worked their way around the annual political donation limit of $10,000 by using family members and even in some cases staff, contributing hundreds of thousands in cash.

A distorted electoral system

Under the 2013 Constitution an electoral system was imposed, supposedly proportional, but designed to elect a President type “leader” with the bulk of the votes, while the rest of his MPs and Ministers had pitifully small numbers.

There was an outrageous ballot paper for one national constituency without names, faces, or party symbols just one number among more than 200 from which Fiji’s largely undereducated voters were to select one number.

Voters were not allowed the help of even a “voter assistance card” (common in all democratic countries) which was astonishingly made illegal with heavy fines.

This utterly contrived electoral system was given the stamp of approval by many authoritative figures such as the Catholic cleric Rev David Arms and even self-censoring USP academics whose academic journal covering the 2014 elections blazoned “ENDORSED” on their cover.

That system was perpetuated through the 2018 Elections and is now in full swing for the 2022 elections.

The outcome of those elections will be interesting to say the least, given that under the Constitution the RFMF can claim legal responsibility for safeguarding the welfare of Fiji, which may be what they decide themselves.

Between a rock and a softer place?

Of course, Fiji’s voters might also want to examine the impact of the two coup leaders on the public debt, FNPF and the economic welfare (and poverty) of ordinary people of Fiji (perhaps my next three articles).

But even the very simple comparisons and contrasts that I have drawn above between Rabuka and Bainimarama in their governance of Fiji, would suggest that Fiji is not between “the rock and a hard place” but “between a rock and a softer place”.

I am sure that The Fiji Times readers are intelligent enough to decide who is the “rock” and who is the “softer place” – regardless of the skeletons rattling in both their cupboards.

PROF WADAN NARSEY is a former Professor of Economics at the University of the South Pacifi c and a leading Fiji economist and statistician. The views expressed in this article are not necessarily those of The Fiji Times

Both of these former soldiers have carried out military coups removing lawfully elected Governments.

Is Fiji genuinely between, as the saying goes, “a rock and a hard place”? I suggest that today’s young voters, who have only known 14 years of the governance by the Bainimarama Government, need to think also about how Mr Rabuka governed Fiji after his 1987 coup.

Both coup leaders may have coup skeletons in their cupboards.

But only one is being very selectively focused on by the current RFMF Commander, writing (appropriately) in Fiji’s other daily newspaper.

Fiji’s voters ought to focus on historical facts by answering the following difficult questions about the two coup leaders:

- Who were really behind the coups of 1987, 2000 and 2006?

- How did each coup leader change Fiji’s constitution and Fiji’s governance?

- How did each coup leader change the powerful institutions of state, such as police, prisons and judiciary?

- How did each coup leader influence the media?

- Were our coup leaders collective decision-makers or dictators?

- Were the coup leaders accountable to the voters or to “powers behind the throne

Behind the 1987 coup?

The world knows that Sitiveni Rabuka, the third in command in the RFMF, implemented the first 1987 coup.

But anyone watching the very public protests against the 1987 NFP/FLP Government would have known that the former Prime Minister (the late Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara) and the Governor-General and later President (the late Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau), and all their entourages would have had their ears very close to the ground and, possibly, their fingers in the pie.

But importantly, what did Mr Rabuka do afterwards as coup leader?

Rabuka became multiracial

Victor Lal and Fijileaks rightly remind readers about the trauma that Mr Rabuka’s 1987 coup caused the Indo-Fiji community.

But what needs also to be discussed is Mr Rabuka’s reform of the racist 1990 Constitution and his support of the revolutionary 1997 Constitution.

Mr Rabuka, in partnership with Jai Ram Reddy (Leader of the National Federation Party) agreed to the appointment of the three person Reeves Constitution Commission (Sir Paul Reeves, Tomasi Vakatora Senior and Dr Brij Lal).

Their report was the basis of the 1997 Constitution, with one valuable addition not in the Report.

It is sadly often forgotten today that the 1997 Constitution included a “multiparty government” provision.

This ensured that any party with at least 10 per cent of the seats in Parliament had to be invited to join the Cabinet and share in the governance of Fiji.

Of course, there was one huge defect in its electoral system which I had explained even as I (as a NFP Member of Parliament then) voted to pass the 1997 Constitution (“The Constitution Review Commission Report: sound principles but weak advice on electoral system”. The Fiji Times, November 1, 1996).

But we in the NFP were in a hurry to approve the progressive constitutional change agreed to by Mr Rabuka.

We knew he had to convince some very reluctant colleagues, and we fully co-operated for the 1999 Elections.

I remember accompanying Ratu Inoke Kubuabola in his election campaigns in the Yasawas and Ratu Sakiusa Makutu in Nadroga.

Sadly, both Indo-Fijian and indigenous Fijian voters rejected the multiracial stance of Mr Rabuka and Mr Reddy.

Nevertheless, it is to Mr Rabuka’s credit that he accepted the results of the election and humbly offered his services to Mahendra Chaudhry as the incoming PM (on the phone in my presence on the Vatuwaqa Golf Course).

Unfortunately, for reasons that historians can explore till the cows come home, Mr Chaudhry did not accept that humble offer from Mr Rabuka, who soon after lost the leadership of SVT to Ratu Inoke Kubuabola.

Ignored today are the following:

- that the historical opportunity to implement a multiracial multiparty government (of the Fiji Labour Party and Mr Rabuka’s Soqosoqo Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT) party went begging. Thus the cogs of the 2000 coup were set in motion;

- that the 1997 Constitution had an upper house – the Senate which was a solid “checks and balances” mechanism of national leaders, and which could officially hold the decisions of the elected House of Representatives to account;

- that by and large the institutions of government were relatively independent of the Government of the day. Less clear are the events of 2000.

Behind the 2000 coup?

It is a real tragedy that while George Speight is seen as the leader of the 2000 coup, the truth has never been revealed about who else, including military officers, might have had more than just a sticky hand in it.

It is a real tragedy that Fiji has forgotten the names of a few honest RFMF officers who were very ethically opposed to the 2000 coup. From personal communications to me, I list the following: Ilaisa Kacisolomone, George Kadavulevu, Vilame Seruvakoula, Akuila Buadromo and several others.

But also conveniently forgotten are the names of RFMF officers who were at least initially behind the 2000 coup, many revealed by the Evans Board of Inquiry Report (which can be freely downloaded from the TruthForFiji website).

What is historically indisputable is that after RFMF gained control of the situation Mr Bainimarama chose not to restore the lawful Chaudhry Government to power but appointed the interim Qarase Government, thereby effecting the real coup.

It is said that some of the CRW soldiers involved in the November 2000 mutiny did so because they felt betrayed by some in the RFMF hierarchy.

It is not disputed that a number of CRW soldiers (not necessarily involved in the mutiny) ended up dead after the mutiny in circumstances not known to this day.

It is not in dispute that Mr Rabuka, with his uniform, appeared at Queen Elizabeth Barracks at the time of the mutiny.

But while one newspaper is focusing on his actions, the roles of several other senior RFMF officers during the 2000 coup are not being similarly examined.

2006 and governance since then

Now we come to the 2006 coup.

In contrast to those which went before, there is no doubt whatsoever that the then RFMF Commander Mr Bainimarama was the sole leader of the 2006 coup and totally controlled the Government thereafter, while still controlling the RFMF.

Given what have I sketched above, the sheer contrasts of the Bainimarama coup with the Rabuka coup are all too obvious.

It is tragically forgotten that the 2006 coup did not just depose Mr Qarase’s SDL Government.

It deposed a multi-party government – a government of Mr Qarase’s Soqosqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua (SDL) Party and FLP.

One can understand why Mr Chaudhry as FLP leader has never emphasized that point.

Soon after the 2006 coup he joined Bainimarama’s Government as Minister of Finance.

It is indisputable that Mr Bainimarama ruled Fiji for eight years as the head of a military government which was not democratically accountable to the Fiji public.

A “People’s Charter” exercise was carried out under the leadership of John Samy and the late Archbishop Mataca but rejected without explanation.

Professor Yash Ghai’s Constitutional Commission was appointed by Bainimarama and Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed- Khaiyum.

It produced a comprehensive draft constitution, but Professor Ghai and his Commission were also were sent packing for reasons never clarified.

A 2013 Constitution with little popular input was imposed on Fiji without the approval of any elected Parliament.

The Senate was abolished.

Parliament has become a rubber stamp for the legislative changes the current government wants.

Many important institutions of Government were allowed by the Constitution to come under the direct or indirect control of the politicians who controlled the Government.

Large sections of the media (with the painful exception of The Fiji Times) and the Media Industry Development Authority came under Government influence or control.

Undermining the Ministry of Information, a massive amount of money was spent annually on American propaganda machine Qorvis.

One Government Minister, not the Prime Minister, clearly became all powerful while others toed the line or were ejected from Parliament.

To fund the ruling party’s electioneering, the owners of some of Fiji’s largest businesses have worked their way around the annual political donation limit of $10,000 by using family members and even in some cases staff, contributing hundreds of thousands in cash.

A distorted electoral system

Under the 2013 Constitution an electoral system was imposed, supposedly proportional, but designed to elect a President type “leader” with the bulk of the votes, while the rest of his MPs and Ministers had pitifully small numbers.

There was an outrageous ballot paper for one national constituency without names, faces, or party symbols just one number among more than 200 from which Fiji’s largely undereducated voters were to select one number.

Voters were not allowed the help of even a “voter assistance card” (common in all democratic countries) which was astonishingly made illegal with heavy fines.

This utterly contrived electoral system was given the stamp of approval by many authoritative figures such as the Catholic cleric Rev David Arms and even self-censoring USP academics whose academic journal covering the 2014 elections blazoned “ENDORSED” on their cover.

That system was perpetuated through the 2018 Elections and is now in full swing for the 2022 elections.

The outcome of those elections will be interesting to say the least, given that under the Constitution the RFMF can claim legal responsibility for safeguarding the welfare of Fiji, which may be what they decide themselves.

Between a rock and a softer place?

Of course, Fiji’s voters might also want to examine the impact of the two coup leaders on the public debt, FNPF and the economic welfare (and poverty) of ordinary people of Fiji (perhaps my next three articles).

But even the very simple comparisons and contrasts that I have drawn above between Rabuka and Bainimarama in their governance of Fiji, would suggest that Fiji is not between “the rock and a hard place” but “between a rock and a softer place”.

I am sure that The Fiji Times readers are intelligent enough to decide who is the “rock” and who is the “softer place” – regardless of the skeletons rattling in both their cupboards.

PROF WADAN NARSEY is a former Professor of Economics at the University of the South Pacifi c and a leading Fiji economist and statistician. The views expressed in this article are not necessarily those of The Fiji Times

"It is sadly often forgotten today that the 1997 Constitution included a “multiparty government” provision. This ensured that any party with at least 10 per cent of the seats in Parliament had to be invited to join the Cabinet and share in the governance of Fiji." Wadan Narsey

Fijileaks: Our Editor-in-Chief had consistently opposed the mandatory multi-party power-sharing government provision in the 1997 Constitution and still stands by his criticisms. The following article first appeared in the Fiji Sun in 2003 and was reproduced by online websites and quoted in academic journals.

Analysis

FIJI’S MANDATORY POWER-SHARING AND ELECTORAL SYSTEM NEED A COMPLETE OVERHAUL

By VICTOR LAL

The Supreme Court has delivered its verdict. But the judges cannot solve the political and constitutional conundrum relating to the controversial provision mandating a multi-party Cabinet. It is clear that the Supreme Court judges employed Constitutional Interpretation, which proposes the argument for interpreting the Constitution according to its 'original intent' rather than Constitutional Construction, which allows the judges the flexibility to rule on constitutional matters in the light of situational contexts. They ordered the politicians to sort out the constitutional mess.

It is time for the politicians themselves to finally confront the great constitutional juggernaut of power sharing, which has blighted politics and governance in Fiji.

The word juggernaut derives from the Hindi Jagannath, lord of the world, and a title for the Hindu god Lord Krishna. Votaries were said to cast themselves under the wheels of the massive cart on which his image was dragged in procession at Puri in India.

In plain terms, juggernaut translates into an irresistible destructive force. Like the Jagannath, the 1997 Constitution of Fiji has, since its inception, been dragged from one court to another following the September 2001 general elections, which controversially returned the SDL, under Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase, as the winner of the largest number of seats. In the process, the Constitution seems to have become a destructive force in the proper administration of the country.

The great American constitutional scholar Martin Shapiro, in a seminal book entitled In Law and Politics in the Supreme Court, published nearly three decades ago, cautioned against seeing the US Supreme Court only through the lens of constitutional interpretation because it made both too little and too much for the Court – too little because it ignored the Court’s role as policymaker in constructing federal statutes and too much because, by placing the Court at the center of the constitutional universe, it magnified the Court’s importance in the political system out of all proportion.

Similarly, our own Supreme Court of Fiji, under the chairmanship of the Chief Justice Daniel Fatiaki, had been called upon to resolve ambiguities in the meaning of constitutional principles whose seeds reside elsewhere: in the intractable and contentious concept of mandatory power-sharing in the Constitution of Fiji. As we will see later, the problem, and the solution, is political rather than legal. It lies in the hands of the elected politicians and not the esteemed and learned judges.

In fact, this was also the point conceded by Professor George Williams, the Australian lawyer representing the Fiji Labour Party. When questioned by the justices on what would happen should the Supreme Court rule in favor of the former Prime Minister Mahendra Chaudhry, George Williams QC, replied that if that was so "the matter is political rather than legal". In other words, the resolution of the constitutional conflict lies in the political rather than the legal field.

Moreover, there is no mechanism in the Constitution of Fiji, which empowers the Supreme Court to force one of the belligerent parties to abide by its final ruling. No mountain of legal judgments for or against Qarase or Chaudhry will solve the fundamental flaw in the power-sharing concept in the Constitution of Fiji.

And the Prime Minister Qarase was correct to have insisted throughout that the mandated power sharing, in his and his party’s opinion, was cheating them of the electoral right to rule the country. Also, that it was undemocratic because it stifled opposition politics, and the absence of an opposition party could reduce his government’s accountability.

In this particular constitutional case, therefore, the Supreme Court judges had to employ one of the two following choices: (i) to abide by the time-honored tradition of constitutional interpretation, which is the province of the courts, or (ii) be audacious enough, in the footsteps of the great reforming English judge Lord Denning, and call upon the quarrelling parties to opt for constitutional construction, the elements of which, although bargained over elsewhere (in private committee room), are invariably settled in Parliament.

In other words, a constitutional settlement must be reached outside the Supreme Court of Fiji. The politicians could have been asked to review the Constitution, and reform the controversial power-sharing provision in the Constitution of Fiji, including the skewed electoral system that was foisted upon the electorate.

Power Sharing Concept: Prime Minister’s Views

Since the promulgation of the 1997 Constitution of Fiji, there have been endless surprises and arguments over the interpretation of what constitutes multi-party government. There are those who argue that a multi-party government is mandatory in Fiji, and there are those who argue, as highlighted in the Reeves Commission Report, that it is to be a coalition of like-minded parties. Conversely, if political parties are not-like minded or unwilling to be like-minded, there is simply no practical or feasible basis for a workable multi-party Cabinet.

The controversial provision mandating a multi-party Cabinet was written and adopted, as Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase told the Australia/Fiji and F/Australia Business Council meeting in October 2002, ‘by former political leaders (Sitiveni Rabuka and Jai Ram Reddy) who had already agreed they would co-operate together in a coalition. In other words, they were writing a constitutional ticket to suit themselves. But in the elections of 1999, the people rejected them decisively’.

I have written on this and other issues extensively elsewhere. On the above point, even Jon Fraenkel of the University of the South Pacific (The Failure of Electoral Engineering in Fiji, 2000) concurs with Qarase: ‘The new system had been virtually tailor-made to deliver Prime Minister [Sitiveni] Rabuka back into office, although this time in alliance with Indo-Fijian opposition leader, Jai Ram Reddy.’ We will return to the drawing up of the controversial power-sharing compact in the constitution. The Prime Minister Qarase also informed the audience as to why he does not like the multi-party Cabinet law:

‘It is undemocratic, unrealistic and not relevant for the current political situation. I am pretty sure Mr [John] Howard; [the Prime Minister of Australia] would feel the same way if Australia had the same requirement! It effectively compromises the democratic convention as you have here in Australia that the political party or parties that win an election should form the Government, and the Prime Minister has the sole authority to choose his Ministers, based on his political judgement. We do not believe it is acceptable or sensible to legally force parties with diametrically opposed policies and belief to work together in Cabinet. That, to us, is a formula for political chaos, deadlock and strife, and weak government. The SDL would be under constant pressure to change the manifesto, which brought it to power. Wholesale betrayal of the electorate is not a foundation for sound and stable government. It is also a political absurdity that in certain circumstances the SDL, the major party in the House, might end up with fewer Cabinet positions than [Fiji] Labour [Party].’

Qarase also asserted that he believed that he had complied with the Constitution and that was what he would be arguing in his appeal to the Supreme Court of Fiji. ‘Strangely, a small and misguided political group,’ he said, ‘is arguing that we should not be appealing on this issue’. ‘They think we should abandon our constitutional right and blindly follow the multi-party Cabinet path they think is best for the country’.

As I have written elsewhere, I would place a major portion of the blame on the problem of power sharing in the Fiji Constitution on the constitutional designers. One of the key figures in the constitutional discussions was American Professor Donald Horowitz. He argued that the alternative vote system would ‘make moderation rewarding and penalize extremism’. The system was said to be ‘perfectly apt’ for Fiji. ‘It is an electoral system that meets the test of simplicity of operation, lack of ambiguity in producing electoral results, and conduciveness to the goal of inter-ethnic accommodation’, wrote Horowitz. In practice, as Jon Fraenkel pointed out, the system proved extraordinarily complex, the results remarkably ambiguous and its merits as a tool for promoting ethnic co-operation were highly questionable.

There are two commonly referred to institutional approaches that deal with easing of ethnic tensions and power sharing in divided societies, one associated with the Dutch political scientist Professor Arend Lijphart and the other with Donald Horowitz. (Fijileaks: Our Editor had consulted both of them during the writing up of his Fiji's Racial Politics: The Coming Coup). The Lijphartian approach emphasizes powerful elite that leads the region way from ‘centrifugal tendencies’ through a system of power sharing (the recommended electoral system being list proportional representation).

Horowitz criticizes the Lijphart view, claiming that a strong leadership that reinforces ethnic divides (by encouraging coalitions based on ethnies) will only lead to harmful competition, intra-ethnic flanking (generally defined as competition within groups), and more violence. This second, Horowitzian approach, instead touts moderation and the crossing of ethnic lines in both voting and in subsequent government institutions (the recommended electoral system is the alternative vote).

Horowitz typically proposes ‘centripetal, integrative or incentive based techniques’ as opposed to Lijphart’s ‘consociational’ mechanisms. Indeed, the two have often gone head to head in real life electoral engineering, as was the case in the 1996 constitutional engineering of Fiji. Each of them submitted their ideas to the Constitutional Review Commission and it was Horowitz’s incentive based alternative based vote system that made it into Fiji’s 1997 Constitution.

However, the alternative vote system, as I have written elsewhere, must be largely held responsible for the ensuing instability following the 1999 and 2001 elections in Fiji.

In fact, Fiji was not the first time the Horowitz and Lijphart debate had surfaced in regard to the electoral rules of a divided society. Both had also written and debated its application in a post-apartheid South Africa: Lijphart (Power Sharing in South Africa, 1984) and Horowitz (A Democratic South Africa? Constitutional Engineering in a Divided Society, 1991). We will deal with South Africa in due course. (Fijileaks: Our Editor had also completed a lengthy study: Fiji and South Africa - Strange Bedfellows, Apartheid in South African and Fijian Constitutions (especially Rabuka's 1990 Constitution)

The 1997 Constitution: A Tortured Existence

The 1997 Constitution, which the former Prime Minister and the Father of Military Coups in Fiji, Sitiveni Rabuka, claimed in October 1997 as a challenge to sail into ‘unchartered waters’, so to speak, was modelled on the post-apartheid South African Constitution.

The first election, under the new untried concept of mandatory power sharing in Fiji, was held in 1999. The result, as we know, saw the Peoples Coalition, led by Chaudhry, capture 52 out of the 71 seats. Besides the Fijian Association Party (FAP), led by Adi Kuini Badavra Speed, Chaudhry invited minority parties, which were not entitled as of right to be in his Cabinet. And the Christian Democratic Alliance-the Veitokani Ni Lewenivanua (VLV), the General Voters Party, and a few independents joined him. So at the end of the day, the Peoples Coalition had 58 out of 71 members sitting on the Government benches with only 13 on the Opposition.

The 1999 election results showed that the SVT polled 38% of the total Fijian votes and 19.8% of all votes and got only 8 seats. The FAP polled 18% of total Fijian votes and 13.20% of all votes but got 11 seats. The NFP polled 27% of total Indo-Fijian votes and 14.91% of all votes and got no seats. The FLP polled 53.3% of total Indo-Fijian votes and 31.74% of all votes and got 37 seats. The FLP polled less than 2% of Fijian votes but got 37 seats, the biggest number of seats for any political party. Out of the 3, only 6 were Fijians and those Fijians were elected in national seats with the majority of support of Indo-Fijian voters. The elections produced these results because Indo-Fijian voters voted as an ethnic bloc. Fijian voters, on the other hand, were split and fragmented among more than five political parties and independents.

As far as Rabuka’s SVT was concerned, it lost 18 of the 23 Fijian communal seats where only Fijians stood and Fijians voted in the elections. The SVT, which still represented the vast majority of Fijian voters (38%), was however swept aside by Chaudhry on a constitutional technicality. He shut the SVT out of his government because it made unacceptable political demands. In any event, most SVT members had agreed with Jim Ah Koy to remain in Opposition. The SVT’s chief coalition partner, the National Federation Party (NFP), failed to win a single seat. It lost all 19 Indo-Fijian designated seats to Chaudhry’s Labour Party. The NFP was completely humiliated and annihilated from the political map. In his Cabinet, out of 18 Ministers, Chaudhry had 12 disparate groups of indigenous Fijians and only six Indo-Fijians.

The Constitution, however, made him both the victor and the vanquished. He had, after all, gone into the election with grave reservations about the new electoral system. Even during the discussions over the promulgation of the 1997 Constitution, Chaudhry was only one of a very few politicians who foresaw constitutional problems which might emanate from it. The Joint Parliamentary Select Committee (JPSC) altered the Reeves Commission recommendations, which dealt with the House of Representatives.

Instead of the proportion of reserved to open seats that the Commission had recommended, the Commission reserved it, with 46 seats being reserved or communal and 25 being open. Of the 46 reserved seats, 23 were to be Fijian, 19 Indo-Fijian, the three General Electors and one Rotuman. The JPSC recommended basically staying with the provincial boundaries, meaning that the spectre of provincialism might well continue. Rabuka, according to his biographer John Sharpham, had argued against it, calling it ‘this ugly animal called provincialism’. As Sharpham observed, ‘by not accepting the Commission’s suggestion to more equitable constituencies the question of provincial impact would have to be tested in the next election’.

A major recommendation of the Committee went beyond what the Reeves Commission had proposed, which was to allow power sharing to emerge from agreement and the electoral changes that would create multi-ethnic parties and coalitions. Instead the Committee built on a proposal put forward by the NFP-FLP submission and put in place a formal arrangement for power sharing in the Cabinet. The Cabinet would be multi-party with its size determined by the Prime Minister. The former NFP leader Jai Ram Reddy, in particular, shared the concept of power sharing. He told the House: ‘Whilst the concept of power sharing is admittedly difficult to work, the alternative, which we have now, of one community in government and one in opposition, is infinitely worse, and could in the end prove disastrous.’ Rabuka also embraced the concept of power sharing. After all, the new 1997 Constitution was the handiwork of Rabuka and Reddy who happened to be the key political players after the 1994 elections, and were widely expected to its beneficiaries in any future elections.

Chaudhry, on the other hand, remained defiant, provoking a virulent attack from Reddy who accused the FLP leader of misleading the public and of cheap political grandstanding. As Sharpham has pointed out, Chaudhry ‘despite signing off on the Report, still had major misgivings’. He opposed ‘the provincial allocation of Fijian seats, pointing correctly to the ethnic divisions of the past’. He was also ‘unhappy about the electoral arrangements, seeing in them the perpetuation of the old racial divisions’. He was, in Sharpham’s words, ‘in typical Chaudhry fashion, unhappy with the result, and said so forcefully in Parliament’.

In a cruel twist of irony, Chaudhry and his Fiji Labour Party found themselves elected under the same electoral system. Now, the race for the coveted post of Prime Minister began, with Chaudhry leading the pack. Once the official election results were announced, the Labour Parliamentary caucus elected him as the party’s nominee for prime minister. Soon afterwards, the President Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara appointed him Prime Minister.

Chaudhry fights corner to be PM

But his Fijian Coalition partners claimed that they were neither consulted nor informed, and reacted angrily, claiming Chaudhry’s appointment a breach of an implicit agreement to have an ethnic Fijian as prime minister. The FAP had decided that they would only join the FLP if party leader Adi Kuini Vuikaba Speed was made Prime Minister. They said they would not join unless their stipulation was met. Viliame Saulekaleka said instead of waiting to discuss the issue with them, they were shocked that the FLP had gone ahead in getting Chaudhry sworn-in. It was believed that PANU was also considering opting out of the coalition. PANU would have wanted their leader Apisai Tora to be PM had he won his seat.

But Chaudhry was forthright in his desire to become PM: ‘It is the Labour Party which has the majority in this election and that’s what democracy is all about, and the people have given their mandate, and that mandate must be respected.’ Chaudhry was the obvious party choice for the position, although there were other contenders, including Tupeni Baba, who would later rightly claim that the Indo-Fijian MPs in the FLP had frustrated his (Baba’s) claim to the Prime Ministership (I have been able to collaborate the authenticity of Dr Baba’s claim from several reliable sources).

Although Chaudhry hastily got sworn-in as Prime Minister by virtue of being the largest winning party, he had the tacit support of his political adversary, the defeated NFP leader Jai Ram Reddy, who told the press: ‘One thing is very clear-the people’s mandate must be carried forward. And the people have overwhelmingly voted for the Fiji Labour Party. And the leader of the Fiji Labour Party, I think, is entitled to being the Prime Minister. And I sympathise with that point of view so that’s the correct thing to do. And their support is not marginal, its quite overwhelming. And as he (Chaudhry) put it, I think, the verdict of the people is crystal clear. So I’m hoping that he will be the Prime Minister.’

Chaudhry was sworn-in as the new and first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister of Fiji. One noticeable absentee at the swearing-in-ceremony was Adi Kuini. Her non-attendance, for whatever reason, was later to be taken as a snub and a detrimental move for her party by the FLP. Adi Kuini asked President Ratu Mara to revoke the decision and appoint her as head of government because she was the leader of the largest ‘Fijian’ party in the winning coalition. It is only a matter of conjecture as to what would have been the legal outcome if Adi Kuini, instead of grudgingly accepting to become one of the two deputy PMs, had defied Fijian protocol and Ratu Mara’s chiefly status, to pursue the matter in the High Court, claiming ‘Chaudhry’s appointment a breach of an implicit agreement to have an ethnic Fijian as prime minister’.

Meanwhile, Poseci Bune, the VLV leader, reportedly began canvassing the possibility of heading a broad coalition of Fijian parties in opposition. Tora threatened to pull out of the coalition altogether. The Fijian nationalists proposed to march against the government. Ratu Mara however rejected a request from the FAP to install their leader, Adi Kuini, as the new PM. The letter was delivered to Ratu Mara by FAP official and Bau chief, Ratu Viliame Dreunimisimisi. Mara rejected the letter, saying he had already installed Chaudhry as the leader of the Coalition, and asked them to work with the Coalition. Mara did Chaudhry no favour: he did what the Constitution required him to do as President of Fiji: to appoint as prime minister the member of the House of Representatives who, in his opinion, commanded majority support.

In turn, Chaudhry offered Adi Kuini the post of Deputy Prime Minister. He had outmanoeuvred her. She had two choices: to accept the second top post in the government or sit on the Opposition benches with her former opponents from the SVT. Labour also threatened to invite VLV into Cabinet. After hours of deliberations with party colleagues, Adi Kuni accepted the second deputy prime minister position in the new Cabinet. She quoted Mara’s advice: ‘It was basically appealing to us as leaders to consider the importance of co-operation rather than be at loggerheads with the new government.’ But coalition partner, PANU, expressed its disappointment with Chaudhry’s invitation to the VLP. PANU officials said they did not appreciate the fact that Chaudhry asked another party before even approaching them, their coalition partner. PANU however also accepted Chaudhry’s offer to join the government. Its parliamentary leader- Meli Bogileka- said they had accepted Chaudhry’s offer of two Cabinet seats to them.

Chaudhry also extended an invitation to the VLP and SVT to join Labour in forming government. ‘I hope they respond soon. Labour has the numbers to form government on its own but I would like them very much to join us so that we can have a government representative of all the people in Fiji. I have a duty to provide a stable government as soon as possible.’ Chaudhry was confident that the two parties would take up the offer. He also invited the two Independent General MPs (Leo Smith and Bill Aull) and the lone Rotuman MP, Marieta Rigamoto, to be part of his Coalition.

Chaudhry was suddenly under a siege situation, as minority parties made impossible demands for places in his new Cabinet. In fact, Chaudhry had to delay naming his Cabinet because of demands made on him, especially from the SVT, which had just lost the elections. STV leader Rabuka wrote to Chaudhry saying his minority group will join a multi-party Cabinet if it is given four Cabinet portfolios, including the position of the Deputy Prime Minister for himself, the Ministry of Works portfolio for Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, and Ministry of Finance portfolio for Jim Ah Koy. Rabuka also demanded seats in the Senate and in the boards of state-owned enterprises.

The results of the general election had given Chaudhry such an overwhelming majority to lead the country in the 21st century. But the Constitution had required of him to make an offer to the SVT. It was possible, some argued, that some of the demands being made, especially from the SVT, were being designed to put Chaudhry in a situation where he was damned if he said ‘yes’, and damned if he said ‘no’. What is surprising is that the SVT caucus, according to Rabuka’s biographer John Sharpham, had agreed shortly after the election results were announced, to remain on the Opposition benches, and not be a part of the multi-party government.

Rabuka later claimed that, ‘We had accepted the Prime Minister’s invitation to be part of the multi-party Cabinet on the condition that I become the Deputy Prime Minister. Our collective decision was that because we structured the new Constitution, we should join the multi-party Cabinet of Chaudhry’s government. Our collective decision is that because we were party to the Constitution, we structured the Constitution in our belief that it was good for the country, good for us to have a multi-party Cabinet and to uphold those we decided to be part of the new Government’

The terms put forward to Chaudhry included that Rabuka be also made the Minister for Fijian Affairs. As we have already noted, Chaudhry found these demands unacceptable, specially from a party which was not only soundly thrashed at the polls, emerging with only eight seats, but the fact that it was not even part of the Peoples Coalition in the first instance. ‘I invited them and they wanted to dictate to me their terms which I just cannot entertain’. While Chaudhry seemed like he was under a lot of pressure, political observers insisted he was in too strong a position to be bullied. Unfortunately, while Chaudhry refused to be bullied, he however, bent over backwards to appease the Fijian community at large, and in the process drawing the wrath of his own community in the appointment of his Cabinet. He had to appeal to his Indo-Fijian members of his Government to accept his desire to share power with Fiji’s other communities.

While Chaudhry seemed to have won the first round of the battle, Rabuka resigned from his embattled leadership of the SVT, and went on to become the chairman of the Great Council of Chiefs. Chaudhry allocated Adi Kuini the powerful but sensitive Fijian Affairs portfolio, which made her chairperson of the Great Council of Chiefs, from where she was expelled by the Rabuka Government because of her leadership of the FAP. From hindsight, it was a strategic mistake, for now Adi Kuini suddenly found herself having to deal with Rabuka as the leader of the powerful body when she and her party expected a senior Fijian chief to fill the revered role. Moreover, Rabuka had wanted her Fijian Affairs post as part of the condition to enter Chaudhry’s government.

As he exited from the political scene, Rabuka again blamed the Indo-Fijians for rejecting his party’s philosophy of multi-racialism. There was no call to the indigenous Fijians to shed their own insular and inward looking nationalism. What had caused SVT’s defeat, according to Rabuka, was ‘the personal weaknesses of the candidates, the personal weaknesses of those that were sitting in the last [Rabuka] government, failing to visit their Constituency regularly, the unpopularity of some of the Government policies, the weaknesses in our party machinery and structure’, and of course, ‘my coalition with the National Federation Party (NFP) was one of the causes of the SVT downfall’. It was not THE cause of SVT’s downfall.

The Electoral System: Attack and Defence

As has been demonstrated, the Reeves Commission favoured a government that was multi-ethnic in character. The JPSC however went further-it sought to mandate a multi-party Cabinet under the new voting system. A former parliamentarian and a member of the Reeves Commission, Tomasi Vakatora, was reported as saying that the Fiji Labour Party noticed a flaw in the Alternate Voting System (AV) used in the 1999 May general elections and used it to win. The FLP saw that the AV system could be used to their advantage since voters had no control over where their votes would end up. They also took advantage of the expertise that was available to them from their Australian counterparts where the AV system is in use in elections.

Another member of the Reeves Commission, the distinguished Australian-based Indo-Fijian historian, Brij Vilash Lal (no relation of Victor Lal), commented after the election: ‘Labour’s unorthodox tactic breached the spirit and intention of the preferential system of voting, where like-minded parties trade preferences among themselves and put those they most disagree with last. Political expediency and cold-blooded ruthlessness triumphed.’ He was commenting on the loss of the SVT-NFP Coalition. The AV system worked against the Rabuka-Reddy Coalition because Labour gave key preferences to the VLV rather than the NFP even though many of the VLV policies were anti-Indo-Fijian. Many Labour supporters, however, uncharitably accused Brij Lal of trying to ‘fix’ an electoral system favourable to Reddy-Rabuka Coalition, for after all, the distinguished academic was Jai Ram Reddy’s nominee to the Reeves Commission.

The Fiji Times columnist, veteran politician, and respected barrister Sir Vijay Singh, wrote about the new electoral system: ‘Having imposed a politically correct voting system but one plainly beyond the elector's reach, parliamentarians helpfully indulged in legislative manipulations that effectively transferred voting power to party leaders. They had already commandeered the power to over-turn the will of the electorate by expelling an elected member from the House, and the lure of a large lunge at the voting process itself was too irresistible. Rightly believing that most voters would much prefer an easy way out of the compulsorily entered polling booth to mark the complicated preferential ballots, Parliament duly provided for above-the-line voting. This was a corruption of the genuine system that permitted an elector to 'vote'- not for a candidate-but for a party. The ballot paper was then deemed to have expressed the same preference as the party bosses had previously filed with the Supervisor of Elections, even if the voter were ignorant of all else but his party's symbol.’.

Sir Vijay continued: ‘The defenders of the law argue, with some theoretical merit, that the voter was not obliged to vote above the line and had the option to express his preference by voting below line. But party leaders knew that few could or would do so. After further creative thought, they amended the law to allow for a voter to vote for a party above the line even in cases where the party had no candidate below the line! The opponents argue, with much merit, that by these legislative manoeuvres, Parliament may have fallen into a constitutional crevice. They say that preferential voting system having been provided for in the constitution, the authentic system's requirement cannot be modified by Parliament. The constitution clearly meant that every voter must personally express his or her preference by writing the appropriate numbers against the name of a human being who was a candidate, not a party. Those who question the above-the-line voting system provided for in the Electoral Act (and not the constitution) argue that such a law is unconstitutional for it permits an elector to vote for a party-and a party is not qualified to be a candidate.’

Sir Vijay touched on other aspects of the new system: ‘Also, when an elector 'voted' for a party, he didn't vote at all. At best, he merely signified his intention to appoint a party to be his agent or proxy, and, by virtue of a law of dubious validity, he is taken to have adopted the same preferences as that officially filed by party's officials. Voting by proxy or agent in parliamentary elections is so alien a concept, even in totalitarian regimes, that it could only be legitimized by specific constitutional provision. And there is no mention of such a novel phenomenon in the constitution. The opponents' argument is forcefully brought home by the further legislative legerdemain that permitted a party's name and symbol to appear above the line and a voter to vote for it when the party didn't even have a candidate for the seat at stake! The legislative contamination of the authentic preferential system by the provision of above the line voting might well be, constitutionally speaking, below -the-law.’

Professor Stewart Firth of University of the South Pacific pointed out that ‘Labour was advantaged by the preferential system. In other words, you can’t claim that there is a Labour government today simply because of the new voter system. What you can claim at the moment is that the SVT lost heavily because of that system which was deliberately used against it by the Peoples Coalition and the VLP’.

Meanwhile, the 1997 Constitution was taken for granted by the SVT/NFP Coalition as a right of passage to political power. Rabuka’s biographer, John Sharpham recounts Rabuka’s optimism as his grip on the country was sliding by the hour:

‘Monday revealed how difficult it was going to be, for late on Monday it was clear that the election was turning into a rout. Reddy and the NFP were being trounced everywhere and by huge margins. Even key NFP candidates who had been tipped to enter Rabuka’s Cabinet, like Wadan Narsey, the young academic turned politician, were comprehensively beaten. Reddy, who had chosen, like Rabuka to run in an open seat, to prove the principle of multiracial support, was beaten handily. Tired, dispirited and unwell, he was ready to retire from politics forever and return to his successful law practice. The NFP lost all nineteen of the Indian communal seats to Labour. The eleven Open seats that Rabuka had given the NFP as part of the Coalition arrangement were also in jeopardy. The NFP had, effectively been destroyed by Chaudhry and the Labour Party, and by their commitment to the multiparty, multiracial Constitution. It was not just the NFP that was being mauled. The SVT was also in deep trouble. Apart from a few seats in the north and Jim Ah Koy’s win in Kadavu, there was little to show for all the hard work. Preferential voting, the AV system, was working against the SVT. Unless a candidate won on the first count, gaining 50 per cent plus one vote, the seat count then went to preferences. All the opposition parties had agreed to place their preferences against the SVT. It was virtually impossible for the SVT candidate to win if the vote went to preferences. The division among the Fijians, their fragmentation into eleven different parties, was now counting against the party that had been created to unite them.’

Rabuka flew into Suva and called a two-hour meeting with Kubuabola and Jim Ah Koy. To quote Sharpham:

‘The mood in the Prime Minister’s office area was a gloomy one. Workmen moved up and down the hall outside making drastic changes to the rooms on the fourth floor. These refurbishments had been planned for the incoming government, expected to be led by Rabuka. A different Cabinet and a new Prime Minister would be using these improved facilities. Amidst the gloom of his staff and the noise of the builders Rabuka was upbeat. He talked over the options for the future with Ah Koy and Kubuabola. From time to time, his Cabinet Secretary joined them to offer advice about the timing of resigning and conceding. At this stage Rabuka still believed the SVT and the UGP might win twenty seats and so be offered a Cabinet seat. Should they accept and support the multi-party approach? The longer they talked, the clearer the news became that the Labour Party would win a strong mandate. Ah Koy was, from the beginning, all for going into opposition. Eventually the others agreed, but Rabuka wanted to wait another day, just to see the results. He held out no hopes for any change, but the final vote count needed to be announced formally to make the situation absolutely clear.’

We will not go into the events surrounding the overthrow of the Chaudhry government by George Speight and his henchmen, or into the subsequent victory of Laisenia Qarase and his party at the 2001 polls. We will, instead, focus on Rabuka’s court challenge, and its relevancy to the current legal battle.

The Chaudhry-Rabuka Letters

The deposed Prime Minister Mahendra Chaudhry was one of the first leaders to cast aside the defeated SVT leader Sitiveni Rabuka’s demands for power-sharing in his Coalition government as mandated by the 1997 Constitution of Fiji.

In the 1999 case of The President of the Republic of Fiji Islands and Inoke Kubuabola and Others, the Supreme Court noted that the central purpose of the 1997 Constitution is the sharing of power. The Republic of the Fiji Islands is declared in the course of the preamble to be a multi-racial society. While some particular protection of Fijian interests is contemplated by section 6(j), political power is to be shared equitably amongst all communities: section 6(1). By section 99(3) the cabinet is to be multi-party. Sharing of power means limitation of power. This concept of sharing permeates sections 64 and 99.

Delivering the main judgment, the former Chief Justice Sir Timoci Tuivaqa hoped that the court’s opinion would be useful in future in deciding controversies about the Constitution: ‘In the interpretation of a provision of this Constitution, a constitution that would promote the purpose of object underlying the provision, taking into account the spirit of this Constitution as a whole, is to be preferred to a construction that would not promote the purpose or object.’

The Supreme Court had been called upon to rule on Senate appointments following the 199 general elections.

Analysing the 20th May 1999 correspondence between Chaudhry and Rabuka, the Chief Justice ruled that these were clearly conditions. He said the Prime Minister Chaudhry, acting reasonably, was not bound to accept. The Constitution does not provide for an acceptance qualified in this way. In the circumstances, what purported to be conditional acceptance amounted to a declining of the invitation. As already indicated above, the STV later disclosed that their conditional offer to Chaudhry was merely a ploy to enable them to remain on the Opposition benches in Parliament. But, surprisingly, when a similar situation arose following the 2001 elections, they did not hesitate to condemn the new Prime Minister Qarase.

The Qarase-Chaudhry Letters

On 10 September 2001 the newly elected Prime Minister Qarase invited Chaudhry, as the leader of the second largest party, to join the multi-party Cabinet as required by the Constitution but made it clear that, ‘we think you might be happier in Opposition’. He explained the underlying reasons: ‘The policies of my Cabinet will be based fundamentally on the policy manifesto of Soqosoqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua [SDL], as the leader of this multi-party coalition. Our policies and your policies on a number of key issues of vital concern to the long-term stability of our country are diametrically opposed. Given this, I genuinely do not think there is sufficient basis for a workable partnership with your party in my Cabinet. Indeed, for my party, there can be no compromise on these issues. We have been given a clear and decisive mandate by the people who have voted my party in with the largest representative group in the House of Representatives. As such, we have no mandate to make any changes or adjustments to the policies on which we have been elected.’

Qarase also explained: ‘There is also the make up of the House of Representatives as the outcome of the general elections. We are the majority party and it is simply inconceivable that we should allow a situation where we become the minority group in a Cabinet we have been entrusted both by His Excellency, the President, and by the people to lead. What Fiji needs is a stable Government and the [SDL] is fully capable of delivering that with its coalition of like-minded parties and individuals. I have set this out very clearly because in the present circumstances, the requirement under section 99(5) of the Constitution is both unrealistic and unworkable. However, I give you and the whole country a firm assurance that we shall govern Fiji in the best interests of all its people.’

In other words, Qarase wanted Chaudhry to assume the mantle of Opposition leadership for reasons explained. Ironically, history seemed to be repeating itself. When asked to comment on a Peoples Coalition Government that was heavily stacked against the SVT Opposition, this is what Chaudhry had to say in 1999:

‘I don’t think we need an opposition because we are doing everything for the people. I had invited the SVT to join us. If they had been reasonable with their demands, they might also be sitting with us, but the Opposition are free to do what they want. There are as many as five independents that won their seats. Two of them, off course, are former GVP. They’ve decided they’ll join the government. The gentleman (George Shiu Raj) who won the Ra Open seat has also pledged his support for the government, and that leaves two independents. I don’t know what they will find out on the 14th of June.’

He also found nothing wrong, despite a national outcry, when he appointed his son [Rajendra Pal Chaudhry] has his official private secretary.

In a reversal of roles, the Fiji Labour Party (FLP), in 2001, was to accuse the Ra Open MP and current Minister for Multi-Ethnic Affairs, George Shiu Raj, as a token face of Qarase’s multi-racialism.

Meanwhile, in response to Qarase’s letter, the FLP, while trying to cut a political deal with their former arch-rivals and jailors in the Conservative Alliance, and other minor parties to form an alternative government, accepted Qarase’s offer in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution, and surprisingly, with that of the Korolevu Declaration (Parliamentary Paper No 15 of 1999). In his first letter of the 10th September Chaudhry, as parliamentary leader of the FLP informed Qarase: ‘Let me first congratulate you on your appointment as Prime Minister of the Fiji Islands.’ He went on to inform the newly elected PM: ‘The FLP Parliamentary Caucus is currently in session and your letter (invitation to join the Cabinet) will be table and discussed at this meeting this afternoon. I will revert to you at the earliest once a decision has been taken on your invitation pursuant to Section 99(5) of the Constitution of the Republic of the Fiji Islands.'

In a follow-up letter on the same day, Chaudhry once again informed Qarase: ‘I have much pleasure in informing you that the FLP Parliamentary Caucus has had mature deliberation on your said offer of today and has authorised me to inform and advice you that the FLP accepts your invitation under Section 99(5) of the Constitution of the Republic of Fiji Islands to be represented in the Cabinet. I thank you for your invitation and FLP looks forward to working together with your party to rebuild Fiji in a spirit of national reconciliation’. There is no reference or allegation of any ‘unconstitutionality’ in Qarase’s appointment by the President as Prime Minister of Fiji. Instead, Chaudhry told Qarase that, ‘my party’s participation in Cabinet and in government will be in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution and with that of the Korolevu Declaration – Parliamentary Paper No 15 of 1999’.

Chaudhry also informed Qarase of Clause 4 of the Declaration, notably the manner in which the Cabinet conducts its business. These are (a) Cabinet decision making in Government be on a consensus seeking basis especially with regard to key issues and policies; (b) Parties represented in the Cabinet may express and record independent views on the Cabinet but Members of the Cabinet must comply with the principles of collective responsibility; (c) Consensus seeking mechanisms in Cabinet should include the formulation of a broadly acceptable framework, the establishment of Cabinet committees to examine any major disagreements on policy issues and the establishment of flexible rules governing communication by ministers to their respective party caucuses.

Replying, Qarase expressed disappointment that Chaudhry had not expressly accepted the basic condition he had set out in his letter that the policies of his Cabinet would be based fundamentally on the policy manifesto of the SDL. He also pointed out to Chaudhry that the ‘Korolevu Declaration’ was a political and not a constitutional document. It was not an enactment of Parliament. His SDL was not a signatory to this political agreement and was, therefore, not bound by it. In any case, Cabinet procedures are set out in the Manual of Cabinet Procedures. Qarase also reminded Chaudhry of his (Chaudhry’s) statements to the press.

Chaudhry is reported to have said that ‘the parties’ (FLP and SDL) ideological differences made them unlikely partners’. He is further reported as saying: ‘A number of our policies are diametrically opposed to each other. It’s not a question of simply getting in there to run a government and then returning to trouble at the first Cabinet meeting. Running a country is serious business and there’s a lot of work to do and if one jumps at the opportunity to run the government without first sorting out some of the fundamentals then I’m afraid it will lead to more instability’. As an example, Chaudhry said he would not concede FLP policies affecting the poor, including the removal of Value Added Tax (VAT).

One of the most intriguing aspects of the acceptance was the FLP’s assertion that it was going to provide ‘Opposition from within’ the Cabinet.

What did the FLP mean?

Did it mean the FLP Cabinet ministers would oppose Government policies for the sake of opposing them?

Did it mean that they that they would be in Qarase’s Cabinet merely for the constitutional sake of it?

In his letter to the President, Chaudhry insisted that he laid down absolutely no conditions to the acceptance of Qarase’s invitation to the FLP to be represented in Cabinet. Similarly the Korolevu Declaration, Chaudhry insisted, could not be interpreted as stipulating a condition to the acceptance of Qarase’s invitation. The procedure for establishing a multi-party Cabinet, he insisted, is laid down in Section 99 of the Constitution. As is to be expected, ‘the Constitution does not provide the finer details of how the proportionate number of Cabinet seats is to be determined, how cabinet portfolios are to be allocated or how significant differences on policy matter are to be resolved in a multi-party government. These are matters for discussion/consultation.’

The Korolevu Declaration, Chaudhry claimed, was subsequently endorsed by Parliament as Parliamentary Paper 15/99. The procedures, practices and recommendations therein were applicable in the event of a dispute or disagreement between the political parties on any subject covered in the Declaration. The fact that the SDL was not a signatory to that document was of no significance in its application. The Korolevu Declaration had established a practice, which was agreed to by all political parties at the time and successfully used in establishing a multi-party government following the 1999 general elections. Chaudhry said Qarase’s insistence that all parties in his multi-party Cabinet must accept unconditionally the SDL manifesto as the ‘fundamental policy guide of Cabinet’ stemmed from Qarase’s apparent lack of understanding of the concept of a multi-party government.

In the same letter to the President, Chaudhry again claimed that vote rigging and electoral fraud on a massive scale was perpetrated on the voters of Fiji in the 2001 general elections. ‘We have sufficient evidence to back our claims. We have filed reports on this with the United Nations and the Commonwealth Observer Missions and are petitioning the High Court to challenge the results in several constituencies,’ Chaudhry said. Interestingly, both the Commonwealth and the United Nations have declared the August 2001 elections as ‘free and fair’ except for minor but expected complaints in any general elections.

Replying to Chaudhry’s assertions, Qarase reiterated to the President the reasons for shutting the FLP out of government. He however hoped that the FLP could best assist in the current situation by accepting the position of Opposition in Parliament. Qarase also pointed out that the invocation of the Korolevu Declaration by Chaudhry amounted to conditions. ‘On Mr Chaudhry’s condition to be consulted, he (Chaudhry) is actually demanding a right that he is not entitled to under the Constitution. In effect, his condition is an attempt to usurp the constitutional authority of the Prime Minister under section 99 of the Constitution. His demand is, therefore, an conditional demand, which I could not and can not accept.’

The 1999 Elections and its Aftermath

The Chaudhry government was cruelly cut short by George Speight’s putsch. However, what followed once again brought to the surface all the pitfalls of the 1997 Constitution. There were those who argued, and rightly so, that the rule of law and constitutionalism should have prevailed during the 2000 crisis. What many fail, or refuse to accept, is that the actions of the key players, from the military, to the president, to the judges, were taken in a revolutionary context. They were justified under the doctrine of necessity. It is very easy for us to argue about constitutionalism now when Fiji has once again reverted to constitutional democracy.

The crisis however exposed many of the weaknesses that were bound to surface. We may recall that once the Court had ruled that the Peoples Coalition Government was the ‘government in waiting’, the Coalition splintered into various factions. The result: 2001 August elections which saw Qarase romp to power, with Chaudhry and others now branding him a racist, a vote-rigger, and a dictator.

And yet the Constitution requires power sharing between two leaders who are diametrically at loggerheads on many fundamental issues. The politics of coalition, once again, is under scrutiny in Fiji.

The Impact of Coalitions: Myth and Reality

A traditional conception of coalition politics might suggest that political parties compete independently during the election campaign to maximise their potential and engage in coalition bargaining only once the distribution of seats are known. But of course in reality electoral competition and coalition bargaining are not so neatly sequential. After all, one matter that voters are likely to be interested in during the campaign is the identity of the new government to be formed.

Most parties want to appear relevant to the business of forming a government in order to attract floating voters. They thus have incentives to suggest that they are well positioned to join a winning coalition. In many countries parties do this either by forming electoral coalitions or at least by signalling with whom they will (and perhaps with whom they will not) try to form a government once the dust has settled and the explicit post-election bargaining begins.

The current coalition concept in the Fiji Constitution defies the above logic.

So does the judgment of the Supreme Court, which ruled that, ‘Section 99 provides an important practical tool by which power sharing is to be achieved. Off course, it requires good faith and honest dealings on both sides of politics. But it does not require prior agreement about policies and political agendas before it can be implemented’.

The 1997 Constitution of Fiji, we have been repeatedly assured, is a great concept, and told to learn from the South African Experience.

Lesson from South Africa- A Failed Experiment

As already noted, the 1997 Constitution of Fiji was modelled on the post-apartheid South African Constitution. In 1994 South Africa, after four years of negotiation, was transformed from an ethnic democracy to a nation that promised an-all encompassing multi-party democracy based on a closed list PR system of elections. With Nelson Mandela as President, his first Cabinet consisted of the Government of National Unity (GNU), a product of the interim Constitution and consisting of ministers from the top three parties, the Africian National Congress (ANC), the National Party (NP) and Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).

The interim Constitution furthered power sharing by entitling any party with 80 or more seats to elect an executive Deputy President. This allowed former President F.W.deKerk of the NP and the ANC’s Thabo Mbeki to hold positions of power beside Mandela.

However, in May 1996, the GNU fell apart when de Klerk formally removed the NP from Cabinet due to difficulties within the National Party; the difficulties mostly grew from the task of having to sit in the Cabinet though no longer holding formal power. Power sharing did continue in the still heated conflict between the IFP and the ANC, and governing and Constitution writing was perhaps easier with the exit of the NP. The final Constitution, written during this time, provided many changes that may have ultimately hurt the NP. The 1999 Constitution ended the formal power-sharing requirement and thus the NP was not asked to sit in any formal Cabinet position after 1996.

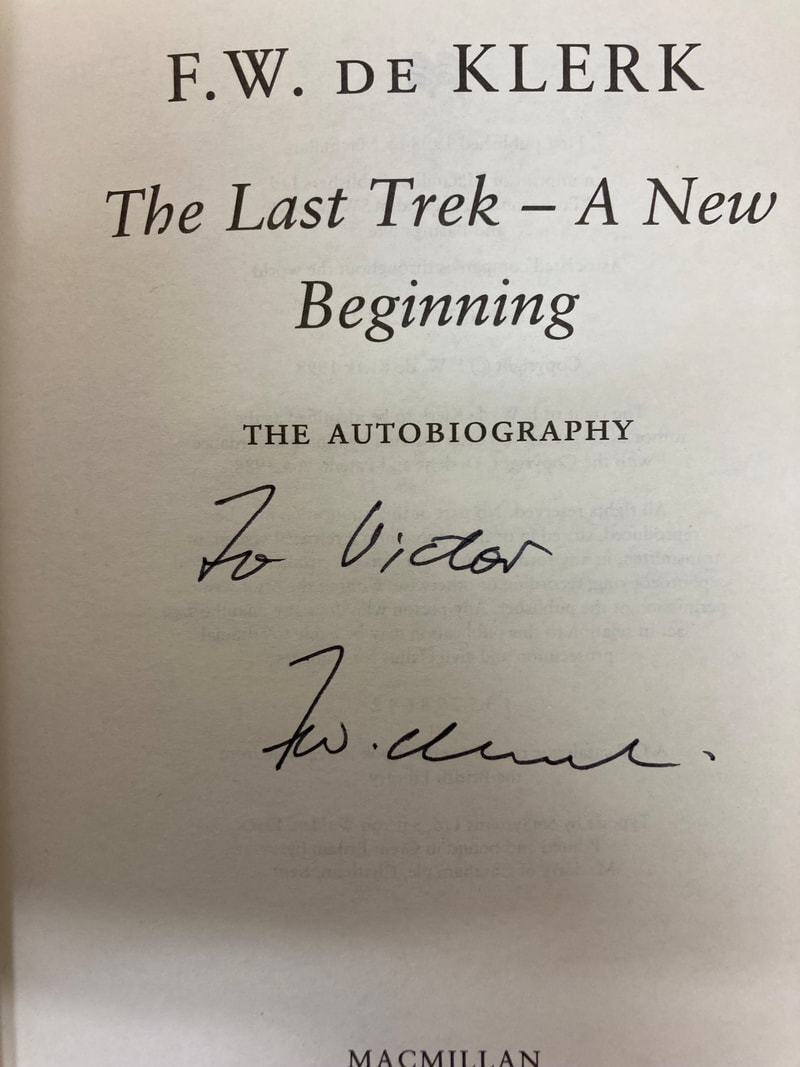

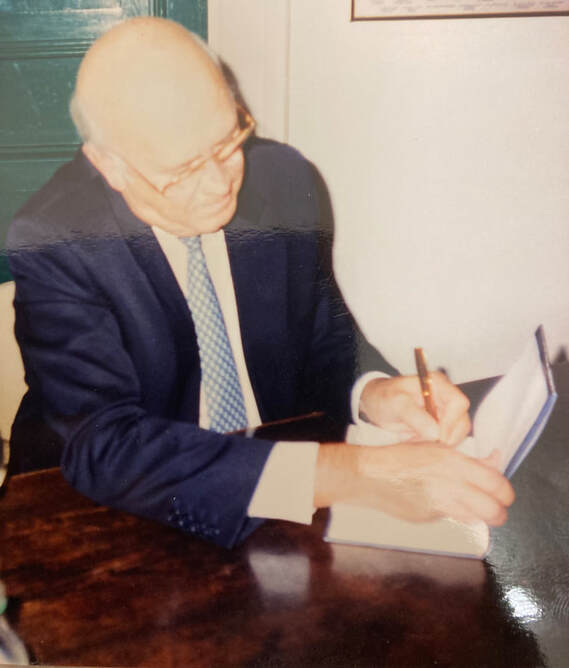

Shortly before the second general elections, de Klerk took his party out of the multi-party Cabinet. He insisted that South Africa needed a strong Government and an effective and watchful Opposition. In his autobiography, The Last Trek-A New Beginning, de Klerk wrote as follows:

‘The Constitution prescribed clear procedures for the formation of the GNU. The first practical task was the composition of the new cabinet. The number of ministers to which each party would be entitled in the GNU was determined by the percentage of votes that it received in the election. According to this formula, the ANC was entitled to 18 ministers, we would have six and the IFP, three. According to the Constitution, the President (South Africa does not have a Prime Minister) could decide which portfolios would be allocated to which parties. He was required to consult with the executive Deputy Presidents both on the division of portfolios between the parties and also on the people who would be appointed to the various portfolios. In the event of a disagreement, the President would decide on the allocation of portfolios, but the leader of the relevant party would have the final say in deciding who should be appointed to the portfolios that had been allocated to his party. Consultation between the President and the Executive Deputy Presidents in the spirit underlying the concept of a GNU was, according to the Constitution, a key requirement.’

But, de Klerk, was accordingly shocked on 6 May 1994 when the newly elected President Nelson Mandela announced the names and some of the portfolios of the 18 Cabinet Ministers to which the ANC was entitled without making the slightest effort to consult de Klerk beforehand. It was the first instance of the ANC riding roughshod over the Constitution when it suited them and was a foretaste of the many difficulties that de Klerk and his party would encounter with the ANC in the GNU.

For the first year or so the new Cabinet functioned surprisingly smoothly. As time went by, differences on policy issues became increasingly evident in Cabinet discussions. ‘These debates,’ according to de Klerk, ‘soon began to reveal the flaws and anomalies in the unnatural constitutional coalition within which we found ourselves. Coalition governments are formed elsewhere in the world because no single party has a majority in Parliament. This leads to the formation of natural coalitions and the acceptance by the participating parties of a common policy framework. The parties often spend weeks hammering out the details of their common policy approach – which then constitutes the cast-iron foundation of the coalition. Despite repeated requests that we should do so, the ANC, with its 62 per cent majority (ANC had failed to win outright majority in the elections) refused to negotiate such a framework with us and the IFP. The result was that we were increasingly confronted with majority government positions with which we disagreed and with which we did not want to be associated. We accordingly insisted on the right to oppose publicly policies where we were at one and the same time part of the government, as well as being the government’s main opposition, attacking it in public. The inevitable result was that both our roles suffered. The ANC was increasingly unhappy when we criticized their policies, and were less inclined to allow us to play our proper role within the GNU. On the other hand, our ability to play an effective opposition role was seriously hampered by our co-responsibility for most of the policies of the GNU.’

By this time it was clear to de Klerk that the GNU was not working. ‘President Mandela clearly had no intention of allowing me and the National Party to play a constructive role. Our anomalous position within the GNU was also beginning to have a very negative effect on our country. Most of the members of our caucus and most of our grassroots supporters wanted the party and its leaders to play a more vigorous and unambiguous opposition role. They were unhappy with the performance of National Party ministers in the GNU – who, they felt, were being dragooned into carrying out ANC policy. On the other hand, most of the Ministers believed that the NP could continue to exert much more positive influence behind the scenes within the power structures of the GNU than they would be able to from the opposition benches. The reality was that, because of the lack of a proper coalition agreement, individual ministers had only limited ability to determine policy, even within their own departments. Increasingly, it was their task simply to operate within the framework of broad policies that had been dictated by the ANC majority,’ de Klerk said.

De Klerk was deeply concerned by this problem. In the end, the National Party decided to pull out of the multi-party Cabinet so that the party could play a leading role in the realignment of South African politics by bringing together a majority of all South Africans in a dynamic new political movement. He told the nation that be believed that the development of a strong and vigilant opposition was essential for the maintenance and promotion of a genuine multi-party democracy.