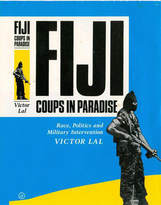

VICTOR LAL: "In 1985 I had interviewed Siddiq Koya, Jai Ram Reddy, Mrs Irene Jai Narayan and other key players who were embroiled in the 1977 political and constitutional crisis for the study that I was writing on Fiji (later published as a book) under Sir David Butler's supervision at Oxford. I had been on personal terms with all the NFP leaders for years, and was also privy to the views and thoughts of the native Fijian chiefly leaders, including the then Governor-General Ratu Sir George Cakobau, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, and Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, for whom my family had long campaigned during the elections. In particular, I was very good friends with the colourful but eccentric Sakiasi Butadroka, the leader of the Fijian Nationalist Party. He was more than happy to grant me an interview. I still vividly remember the shock my father, as president of the Alliance Party Tailevu branch, and my uncle who had just lost to Mrs Narayan in the Suva Indian Communal seat as Alliance candidate, felt when we learned the Alliance Party had lost the April 1977 election to the National Federation Party. I was still in the counting hall, nervously watching the recount my uncle had requested, when I was told of the devastating news.

What happened next, and why Koya did not become the Prime Minister in 1977?

Read the chapter below from my book:"

What happened next, and why Koya did not become the Prime Minister in 1977?

Read the chapter below from my book:"

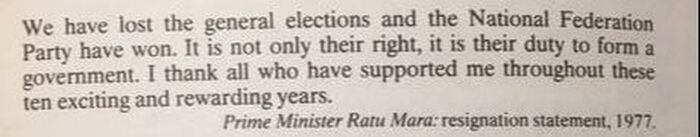

| ON 4 April 1977 about 20,000 Fijians (natives) voted for the radical FNP (Fijian Nationalist Party). For the first time in the country's political history the Alliance Party had been defeated. This defeat paved the way for the NFP (National Federation Party) to form Fiji's next government with the first Prime Minister of Indian (Indo-Fijian) origin: Siddiq Moidean Koya. But this event did not take place. Instead, Fiji entered into an epoch of political instability and confusion. |

On 7 April 1977, 'the day that fooled Fiji', Koya went to the Government House at 4.30 p.m. to be sworn in as the new Prime Minister. But the Governor-General, Ratu Sir George Cakobau, told him that he had appointed Ratu Mara as Prime Minister and had asked his Alliance Party to form a caretaker government. A period of bitter racial and constitutional wrangling followed. If the Governor-General's action had stunned the nation, the defeat of Alliance was equally astonishing. The Nationalists had been waiting on the sidelines as both the Alliance and NFP prepared to embark upon the electoral campaign, a campaign in which several issues was on trial: the staying power of the Alliance, the strength of the Nationalists, the readiness of the NFP as a government-in-waiting, and, above all, the viability of parliamentary democracy.

The members of the House of Representatives had, on 10 February 1977, ended their last session before its dissolution for the 19 March to 2 April general elections with the claim that they had given Fiji a model government. The closest the House of Representatives had come to a constitutional impasse was when, following a vote of no confidence, the former Speaker, R.D.Patel, in 1975, refused to accept that his constitutional obligation was to resign as Speaker.

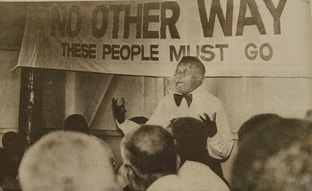

These March/April elections clearly emerged as the most crucial. Indisputably, they were to be a three-cornered fight between the Alliance, the NFP and the FNP. Most political pundits thought the Alliance would remain in office, although the possibility of a coalition or minority government was widely anticipated. Elections in Fiji have always stirred up racial issues and the emergence of the FNP gave fresh impetus to the hatred for the Indians on the part of some Fijians. The Nationalists reiterated demands for constitutional changes, with Butadroka fervently hoping for an NFP victory so that it would reveal to the Fijians that the country was not exclusively theirs:

The members of the House of Representatives had, on 10 February 1977, ended their last session before its dissolution for the 19 March to 2 April general elections with the claim that they had given Fiji a model government. The closest the House of Representatives had come to a constitutional impasse was when, following a vote of no confidence, the former Speaker, R.D.Patel, in 1975, refused to accept that his constitutional obligation was to resign as Speaker.

These March/April elections clearly emerged as the most crucial. Indisputably, they were to be a three-cornered fight between the Alliance, the NFP and the FNP. Most political pundits thought the Alliance would remain in office, although the possibility of a coalition or minority government was widely anticipated. Elections in Fiji have always stirred up racial issues and the emergence of the FNP gave fresh impetus to the hatred for the Indians on the part of some Fijians. The Nationalists reiterated demands for constitutional changes, with Butadroka fervently hoping for an NFP victory so that it would reveal to the Fijians that the country was not exclusively theirs:

That is the day Ratu Mara and his Alliance Fijians must look for. It is the very thing I want to prove to the Fijian people; that this Parliament does not belong to us. The Fijians take it for granted that a Fijian will always be Prime Minister, that a Fijian will always be Governor-General and the ministers for Fijian Affairs and Lands will always be Fijians. I tell them NO. It is not in the Constitution. I wish for the day the Federation will come to power, because it is the very time it will dramatically point out to the Fijians that the government is not ours. | MILESTONE: Faiyaz Koya is not only acting Prime Minister but he is also the first Indo-Fijian to be Minister for Lands and Mineral Resources. The Indo-Fijian politicians were reluctant to take up the position in old days because they were terrified of the chiefs |

As the election fever gained momentum Butadroka and his campaign members visited most rural Fijian areas and explicitly spelled out their message 'Fiji for the Fijians', and went on to lampoon the Alliance's performance, particularly its alleged failure to protect Fijian interests. While asserting that the FNP would form the next Opposition, Butadroka maintained that this would force the Alliance to seek a coalition with the NFP. He was convinced the 'FNP flag would fly in Parliament'.

The Alliance found itself in a dilemma: whether to focus its campaign exclusively on the Fijians or on the population as a whole. The party chose, however, to campaign in force across the country where the FNP threatened to make deep inroads into its support. The offensive, by several prominent Alliance ministers, was led by Ratu Mara who barnstormed across the country claiming that a vote for the FNP would turn Fiji into another Uganda. Describing Fiji as a 'three-legged table', he went on to state that 'if Mr Butadroka's party evicts one section, the Indians, then next comes the General Electors and finally the Fijians will be left in Fiji, which will create a situation like Uganda is facing today. He also asserted that the FNP's main motive were to discredit the Alliance and to work for its downfall, and to create confusion and despondency. In the past Ratu Mara had indicated his early retirement from politics. But now sensing the anxiety among some voters regarding who would replace him, he reassured the nation of his availability because:

"I found that [when] I mentioned my retirement then there were voices completely contrary to the principles of the Alliance that have...formed a party. And as long as that party promotes its course and as long as it remains, I will remain in politics. I refer to the Butadroka party, which wants to send Indians out of Fiji."

This failed to appease the Nationalists or to allay the fears of the Indians. Many thought that it was simply an example of election showmanship. While campaigning on the platform of 'peace, progress and prosperity', the Alliance, to some extent, did specifically concentrate on Butadroka. It chose Tomasi Vakatora, a former Secretary for Communications, Works and Tourism, who was from the same province in which Butadroka had launched the FNP nearly three years ago, to fight him for the Rewa-Serua-Namosi Fijian communal seat.

The Alliance probably calculated that personal rivalry in the NFP between Koya, [K.C.] Ramrakha and Mrs Irene Jai Narayan, which for several months had made the quest for party unity frustratingly elusive, was sufficient to eliminate the Indian-dominated party from the political map. But if the Alliance found comfort in thus dismissing the NFP, it was equally aware of the political perils that lurked in its own backyard: the bitter Indian Alliance dispute over the rejection of Sir Vijay Singh as candidate for the safe Tailevu seat, coupled with the withdrawal from the Alliance by M.T.Kan (an Indian Cabinet minister who had been unsuccessfully prosecuted for corruption), could cost them a lot of Indian votes.

On the whole, the Alliance remained defiant and buoyant, with Ratu Mara apparently not too concerned at the prospect of ruling Fiji with a majority of one. He remarked that Malta's Dom Mintoff was one of the strongest prime minister in the Commonwealth because he had spent so long in power battling with a majority of one. The Alliance also dismissed the electoral threat posed by a young but influential Fijian chief, Ratu Osea Gavidi, who decided to run for Parliament as an independent against the official Alliance candidate in his own Nadroga/Navosa constituency in the western belt of the country.

The NFP, meanwhile, entered the election battle as a collection of disparate groups, busily protecting its own vested interests and beliefs. It did, however, seem to be in tacit connivance with the FNP in an electoral arrangement to defeat the Alliance. The NFP had fielded 35 candidates only; with none for the Fijian or General Elector communal seats, and only two for the National seats. Some of its Fijian candidates had secretly nominated FNP candidates in certain crucial or marginal seats (Victor Lal's Butadroka interview). Despite the fundamental differences in personality of Koya, Ramrakha and Mrs Narayan and their acrimonious conflicts of the previous year they formed an odd but strategic coalition.

The NFP's problem during the general election was to win Indian hearts, minds and votes. Equally pressing was the threat from disgruntled NFP politicians: notably R. D. Patel, who was standing against Koya as an Independent candidate for the Lautoka Indian communal seat; and Vijaya Parmanandam, another Independent, who was contesting the Suva Rural Indian communal seat after failing to be nominated for the same seat on an NFP ticket.

In 1977 Patel, who had resigned as Speaker of the House and from the NFP in 1975, dedicated himself solely to eliminating the embattled Koya as NFP leader. Division within the NFP's grassroots members also widened with Hindus, Muslims and Gujeratis communally splitting along religious, linguistic and provincial lines. For example the contest between Koya (a Muslim) and Patel (a Gujerati) 'was no longer just an election battle between NFP and an Independent. It had become a Muslim versus Gujerati affair'.

To be continued

The Alliance found itself in a dilemma: whether to focus its campaign exclusively on the Fijians or on the population as a whole. The party chose, however, to campaign in force across the country where the FNP threatened to make deep inroads into its support. The offensive, by several prominent Alliance ministers, was led by Ratu Mara who barnstormed across the country claiming that a vote for the FNP would turn Fiji into another Uganda. Describing Fiji as a 'three-legged table', he went on to state that 'if Mr Butadroka's party evicts one section, the Indians, then next comes the General Electors and finally the Fijians will be left in Fiji, which will create a situation like Uganda is facing today. He also asserted that the FNP's main motive were to discredit the Alliance and to work for its downfall, and to create confusion and despondency. In the past Ratu Mara had indicated his early retirement from politics. But now sensing the anxiety among some voters regarding who would replace him, he reassured the nation of his availability because:

"I found that [when] I mentioned my retirement then there were voices completely contrary to the principles of the Alliance that have...formed a party. And as long as that party promotes its course and as long as it remains, I will remain in politics. I refer to the Butadroka party, which wants to send Indians out of Fiji."

This failed to appease the Nationalists or to allay the fears of the Indians. Many thought that it was simply an example of election showmanship. While campaigning on the platform of 'peace, progress and prosperity', the Alliance, to some extent, did specifically concentrate on Butadroka. It chose Tomasi Vakatora, a former Secretary for Communications, Works and Tourism, who was from the same province in which Butadroka had launched the FNP nearly three years ago, to fight him for the Rewa-Serua-Namosi Fijian communal seat.

The Alliance probably calculated that personal rivalry in the NFP between Koya, [K.C.] Ramrakha and Mrs Irene Jai Narayan, which for several months had made the quest for party unity frustratingly elusive, was sufficient to eliminate the Indian-dominated party from the political map. But if the Alliance found comfort in thus dismissing the NFP, it was equally aware of the political perils that lurked in its own backyard: the bitter Indian Alliance dispute over the rejection of Sir Vijay Singh as candidate for the safe Tailevu seat, coupled with the withdrawal from the Alliance by M.T.Kan (an Indian Cabinet minister who had been unsuccessfully prosecuted for corruption), could cost them a lot of Indian votes.

On the whole, the Alliance remained defiant and buoyant, with Ratu Mara apparently not too concerned at the prospect of ruling Fiji with a majority of one. He remarked that Malta's Dom Mintoff was one of the strongest prime minister in the Commonwealth because he had spent so long in power battling with a majority of one. The Alliance also dismissed the electoral threat posed by a young but influential Fijian chief, Ratu Osea Gavidi, who decided to run for Parliament as an independent against the official Alliance candidate in his own Nadroga/Navosa constituency in the western belt of the country.

The NFP, meanwhile, entered the election battle as a collection of disparate groups, busily protecting its own vested interests and beliefs. It did, however, seem to be in tacit connivance with the FNP in an electoral arrangement to defeat the Alliance. The NFP had fielded 35 candidates only; with none for the Fijian or General Elector communal seats, and only two for the National seats. Some of its Fijian candidates had secretly nominated FNP candidates in certain crucial or marginal seats (Victor Lal's Butadroka interview). Despite the fundamental differences in personality of Koya, Ramrakha and Mrs Narayan and their acrimonious conflicts of the previous year they formed an odd but strategic coalition.

The NFP's problem during the general election was to win Indian hearts, minds and votes. Equally pressing was the threat from disgruntled NFP politicians: notably R. D. Patel, who was standing against Koya as an Independent candidate for the Lautoka Indian communal seat; and Vijaya Parmanandam, another Independent, who was contesting the Suva Rural Indian communal seat after failing to be nominated for the same seat on an NFP ticket.

In 1977 Patel, who had resigned as Speaker of the House and from the NFP in 1975, dedicated himself solely to eliminating the embattled Koya as NFP leader. Division within the NFP's grassroots members also widened with Hindus, Muslims and Gujeratis communally splitting along religious, linguistic and provincial lines. For example the contest between Koya (a Muslim) and Patel (a Gujerati) 'was no longer just an election battle between NFP and an Independent. It had become a Muslim versus Gujerati affair'.

To be continued