WHO IS PROTECTING RENEE LAL IN FIJI? OTHER CLIENTS OF HERS ARE ALSO ACCUSING HER OF SWINDLING THEM!

The Gokals (Pratima and Reema) reported her to Fiji Police,

Chief Registrar, LPU and Prime Minister's Office!

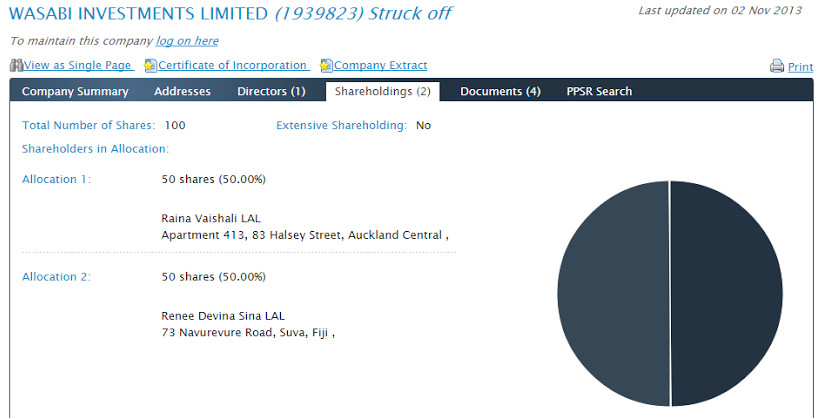

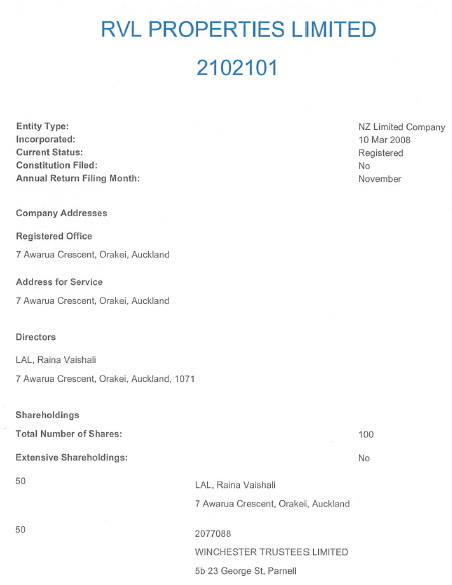

Fijileaks Investigation Team found that Renee Lal allegedly transacted illegal offshore payments to Wasabi Investments Ltd (owned by Raina and Renee Lal sisters) through Exchange and Finance Co Ltd. She allegedly took Jamnadas & Associates' trust cheque payable to ANZ account to go into Reema Gokal's account, and allegedly misappropriated it by getting ANZ to pay Exchange And Finance and then straight to Wasabi using some other clients Reserve Bank approval. We believe the same modus operandi was employed for other misappropriations. Renee Lal is not responding to Fijileaks questions!

"Renee,

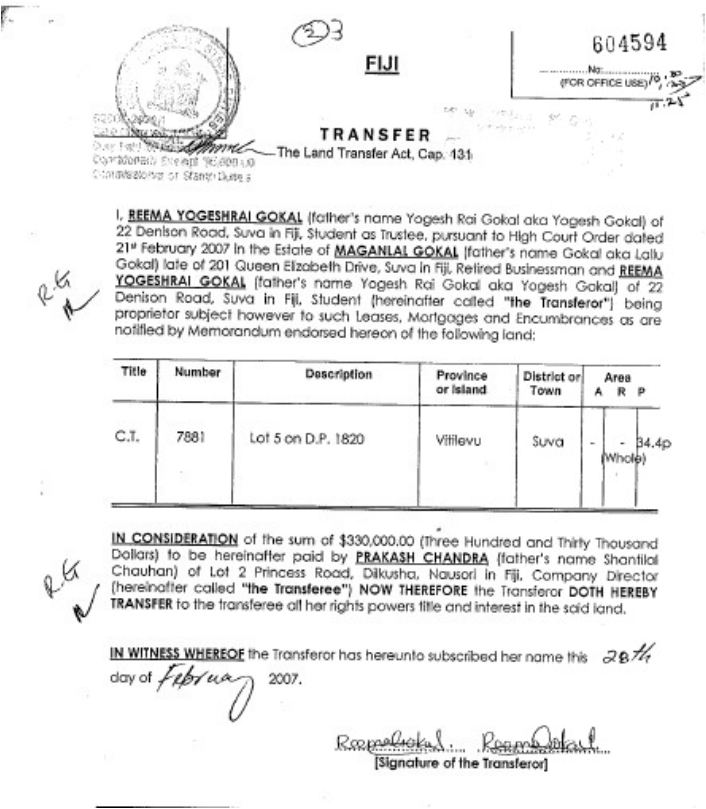

In March 2007 you sold my grandfather's house for $330,000. This money was put into your Trust Account. In August 2012 my mum and I made our very first trip to Fiji to demand [from] you for our trust funds.

We asked you to provide receipts of payments made to Ravi and what was left for me. You said yes to providing the above but as time went by you did not show us anything at all. You even told my mum at your office that over a $100,000 was left for me. You did not show it to us in writing. You had started lying to my mum as soon as we started demanding for our money. You had stole my money and you knew it and so you started telling all kinds of lies to hide that true fact. When we had meetings with you in your office you always looked very nervous and always avoided questions about our money. You never made eye contacts.

In September 22, 2012 me and mum left Fiji because you promised my mum that you would send my share of the money to India in 2 weeks. You told us that you were going to send a BANKDRAFT to India. My poor mum did not know at the time that you were a liar and that you were just bullshiting us.

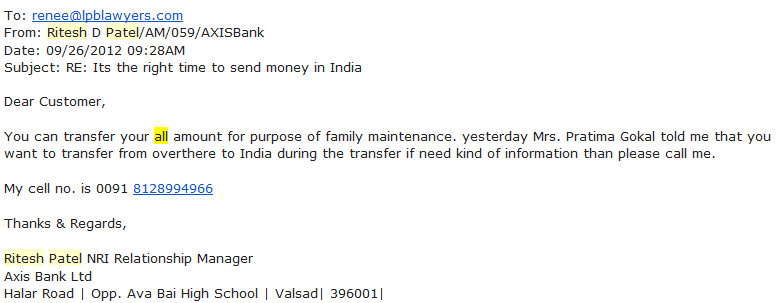

As soon as we reached India your stories started to change, your behaviour became very unusual. You diverted our phone calls. Whenever my mum asked you to send our money you started making excuses and telling lies. For example, im in hospital, im going to NZ, but most of all im very busy today. You always said "Yes dont worry im making arrangements to send your money to India." You told us lies and lies all throughout 2013. You never sent our money. You even played around with our banker Ritesh Patel and told him many times that you were sending money to my account.

Ritesh told my mother that you were just cheating us and doing fraud. You sent emails to Ritesh and made fake phone calls. BUT AT THE END HE REALISED THAT YOU WERE A CHEATER AND THAT YOU HAD STOLEN OUR MONEY. HE UNDERSTOOD YOUR GAMES and explained everything to me and my mother.

In 2013 we started verbally abusing you because we knew that you were never giving our money. We were suffering so badly without money but you just did not bother. We called you so many times but you always diverted your phone. The whole of 2013 me and Ravi threatened you and verbally abused you very very badly but still you did not return our money.

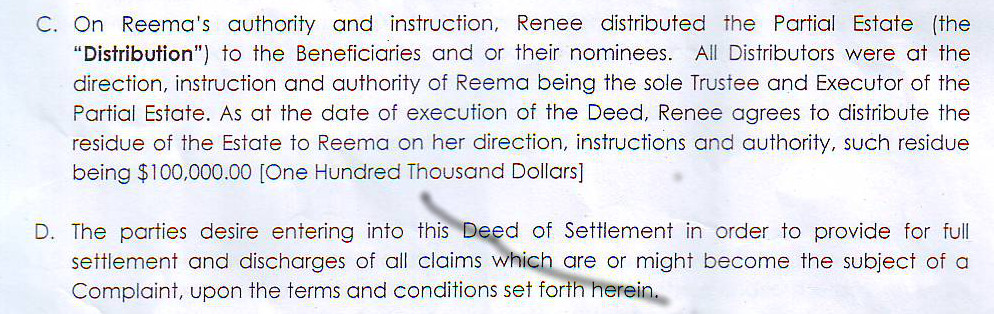

You made a deed of settlement in Feb 2013 but it was all fraud. There was no mention about my money. The amount was not written in your deed and we did not understand all your rubbish as well. My mother became very upset and we were very helpless. YOU COMPLETELY STOPPED COMMUNICATING WITH ME AND MUM BY THE END OF 2013 AND THE WHOLE OF 2014.

In November 2014 me and my mum made our second trip to Fiji to demand [from] you for our money. Our community people in India had paid for our tickets and living expenses. You gave us a horrible time during this trip. You refused to see us at your office. The staff lied to us and always said that you were in meetings but u were just hiding inside your office room. You made us wait outside your office till late in the evening. Once inside your office you swore at me and verbally abused me and my mum. You always called my mum a "BITCH".

You told me straight to my face that you had stolen my money and that was the truth. You said that nobody in Fiji can make u return my money. You told us that THE LPU is a weak body and they cannot do anything to you.

My mother had to threaten you many times using the police because you just did not want to talk about my money. We had to force you to see us in your office. My mother demanded that you show us in writing how much was paid out to Ravi and what remained for me but you refused to provide paperwork.

You put $100,000 owing to me in the deed without a single explanation and without providing us with any accounts. WHERE THE HELL DID U COME UP WITH THE $100,000 FROM? HOW DID U DO THIS CALCULATION? You gave us so much stress and tension and you gave $20,000 to me and again you said that u will send the $80,000 as soon as possible.

As soon as we arrived back to India in December 2014 you completely stopped communication with us and you never sent the $80,000 to India. So again in March 2015 we came to Fiji for the third time to demand for our funds. This time you just hid from us and never showed us your face. You just did not want to face us any more.

You communicated with me over the phone only. You said that you will not return my funds because i had lodged complaints and your main excuse was FIJI LEAKS and my complaints to the PMs Office. This time you just left us by ourselves and we struggled and came back to India." Reema Gokal, copied to Fijileaks

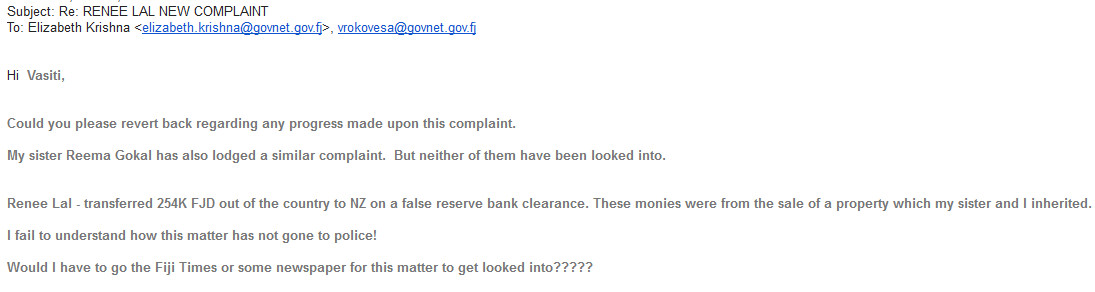

Fijileaks: In the course of our investigation it has emerged that Ms Gokal's brother has also sought help from Prime Frank Bainimarama but to no avail. In his e-mail to the Prime Minister's Office, he has accused Renee Lal of not only cheating his sister of $100,000 but of money laundering. Mr Gokal alleges that Renee Lal transferred $F254,000 out of the country to New Zealand on a false reserve bank clearance.

Fiji Leaks <[email protected]>

Mar 15, to Renee Lal

She sold the property for $330,000

How much she took in fees? - $15,000

How much she paid you in total? $200,000

How much she paid your sister? Almost nothing maybe $20,000 FJD

How much she owes you? AT LEAST $100,000

Did she steal all these money at Jamnadas or after she left?

At Jamnadas. Straight after the transaction was completed, she transferred the money to Wasabi on false clearance. Then she pretended that the money was still in Fiji. She paid for my tuition fees out of her 'own pocket'. So pretending that I was being hit by exchange rate. But in fact 'my money' was in NZ all along. Moreover there are two crimes she committed, firstly stealing our money and not giving any transparent record of its disbursement, and secondly, using a false clearance to move funds out of the country. Breaking the Reserve Bank of Fiji's monetary regulations.

In September 2007 an agreement was made between the plaintiff (Bell) and both defendants (Lals) for the plaintiff to lend both defendants NZ$500,000. The failure of the defendants to repay this loan, in full, is the subject matter of the proceeding:

AUCKLAND HIGH COURT: Woodhouse J noted that the guarantee documents were prepared by the defendants, both of whom are lawyers, or on their behalf, and that evidence proffered in February 2012 by the defendants in protest of jurisdiction - that they could not by that stage recall signing the guarantees - was “disingenuous at the least”.

AUCKLAND HIGH COURT

AUCKLAND HIGH COURT IV-2011-404-5601 [2012] NZHC 1264

BETWEEN

ELAINE CATHARINA BELL

Plaintiff

AND

RAINA LAL

First Defendant

AND

RENEE DEVINA SINA LAL

Second Defendant

Hearing: 23 April 2012

Counsel: E St John for the Plaintiff

R Hollyman and K Simcock for the Defendants

Judgment: 7 June 2012

JUDGMENT OF WOODHOUSE J

This judgment was delivered by me on 7 June 2012 at 4:30 p.m. pursuant to r 11.5 of the High Court Rules 1985.

Registrar/Deputy Registrar

……………………………………

Counsel:

Mr E St John, Barrister, Auckland

Mr R Hollyman, Barrister, Auckland

Instructing Solicitors:

Mr S Palmer, Palmer & Associates Ltd, Solicitors, Auckland

Mr T Mullins, LeeSalmonLong, Solicitors, Auckland

BELL V LAL HC AK CIV-2011-404-5601 [7 June 2012]

[1] The plaintiff claims that the defendants are indebted to her in a sum of $430,000 plus interest as the balance owing on a loan to the defendants of $500,000. The plaintiff obtained leave under r 6.28 of the High Court Rules to serve the proceeding on the defendants in Fiji. The defendants have appeared under protest to the jurisdiction of the New Zealand court. The defendants have now applied under rr 5.49 and 6.29 for an order dismissing or staying the proceeding.

Rules and principles

[2] Rule 6.29(2) provides:

If service of process has been effected out of New Zealand under rule 6.28, and the court's jurisdiction is protested under rule 5.49, and it is claimed that leave was wrongly granted under rule 6.28, the court must dismiss the proceeding unless the party effecting service establishes that in the light of the evidence now before the court leave was correctly granted.

[3] What this means, in practical terms, is that the application for leave, which originally proceeded without notice, is to be determined afresh in the light of all further evidence and submissions for both parties.

[4] The matters that are to be determined afresh are those set out in r 6.28. Rule

6.28(4) is as follows:

An application for leave under this rule must be supported by an affidavit stating any facts or matters related to the desirability of the court assuming jurisdiction under rule 6.29, including the place or country in which the person to be served is or possibly may be found, and whether or not the person to be served is a New Zealand citizen.

In broad terms, this imposes a duty of full disclosure of the matters referred to. Although there were some submissions as to the adequacy of disclosure by the plaintiff on the without notice application for leave to serve in Fiji, I am satisfied that no material issue arises in this regard.

[5] The principal enquiry arises under r 6.28(5), which is as follows:

The court may grant an application for leave if the applicant establishes that--

(a) the claim has a real and substantial connection with New Zealand;

and

(b) there is a serious issue to be tried on the merits; and

(c) New Zealand is the appropriate forum for the trial; and

(d) any other relevant circumstances support an assumption of jurisdiction.

[6] Underpinning the ultimate issue as to whether the New Zealand court should exercise jurisdiction over persons who do not live in New Zealand is the principle that the court does not lightly exercise its discretion to assume such jurisdiction. This is a principle of long standing.1 The High Court Rules applying in this case were amended with effect from 1 February 2009. In Poynter v Commerce Commission2 the Supreme Court confirmed that this principle continues to apply, notwithstanding the recasting of the Rules.

Background facts

[7] This interlocutory application is to be determined, in the usual way, on affidavits for the parties without cross-examination. There are two affidavits from the plaintiff, another affidavit on behalf of the plaintiff, two affidavits from the first defendant, and one from the second defendant. Because there has been no cross- examination, findings of fact on some matters of relevance are necessarily provisional. However, having regard to the affidavit evidence as a whole, some reasonably firm conclusions can be reached on some matters of present relevance.

[8] There was also some evidence on matters which may have relevance in the substantive proceeding but which are of marginal relevance on the present application. Generally these matters are left to one side, without noting them. I have also left to one side matters which in my judgment clearly have no relevance, together with statements in affidavits which amount to submission rather than contentions of fact.

[9] I infer that the plaintiff is a New Zealand citizen, or at least a person who is permanently resident in New Zealand. In early 2007 she was working for a company called New Zealand Home Loan

[10] The first defendant is a Fijian citizen, but in early 2007 was living and working in Auckland. She is qualified and admitted as a barrister and solicitor in Fiji.

[11] The second defendant is a Fijian citizen. She too is qualified and admitted as a barrister and solicitor in Fiji.

[12] The plaintiff and first defendant met in Auckland in early 2007. In March 2007 the plaintiff lent the first defendant $420,000 for three months at an interest rate of 16% per annum for three months. There was no formal documentation. The loan was repaid on or before the three months.

[13] In September 2007 an agreement was made between the plaintiff and both defendants for the plaintiff to lend both defendants NZ$500,000. The failure of the defendants to repay this loan, in full, is the subject matter of the proceeding

[14] The terms of the loan were negotiated over a number of days up to 10 September 2007. Most of the documentary evidence about the negotiations and the conclusion of the agreement is contained in emails. Most of the emails are between the plaintiff and the first and second defendants and between a consultant at New Zealand Home Loans, acting on behalf of the plaintiff, and the first and second defendants. However, it is apparent from the emails that there were some telephone communications between the plaintiff and the first defendant.

[15] In an email on 7 September 2007 the first defendant, for herself and the second defendant, set out loan terms the defendants were seeking and said: “We have all documentation prepared and ready to go so please advise on whether the above is acceptable”. The first defendant said that she could fax the documents and courier the originals and then said: “Alternatively I will be returning to Auckland next Friday and can bring them then”. It appears that “next Friday” would have been Friday, 14 September 2007.

[16] There was a further email from the first defendant to the plaintiff on 10 September at 9:42 am. There must have been some preceding discussion, or written communication, not put in evidence, because the defendants agreed to some modified terms. In relation to telephone discussions I note that the plaintiff and the first defendant both exchanged telephone numbers by email. In the 10 September email the first defendant recorded that one of the things agreed to was “personal guarantees from both Renee and myself” and she said that she had faxed these to the consultant at New Zealand Home Loans.

[17] There was a further email on 10 September, at 11:45 am. This was to the plaintiff from the second defendant on behalf of both defendants. The subject matter is “Final agreement”. The content is as follows:

Elaine

Further to your discussion with Raina this morning we are please [sic] to confirm our agreement as follows:

Loan Amount : $500,000 NZD Interest: 24% per annum Term: 3 months

Security: Caveat over 7 Awarua Crescent, Orakei (we will cover your solicitor’s costs for this)

Personal Guarantees by both Raina & Renee Lal

Interest to be capitalized for the first 3 months. If a further term of 3 months is required the first 3 months of capitalized interest will be paid and interest will be paid monthly thereafter. Please provide your account details in due course.

Thanking you for all your assistance to date.

Looking forward to a long working relationship with you.

Regards

Raina & Renee Lal

[18] The loan amount of NZ$500,000 is the sum that had been the subject of the negotiations from the outset. The interest rate had been in issue, with the defendants originally proposing 20%. The caveat over 7 Awarua Crescent, Orakei, had been offered by the defendants from the outset. The second defendant is the registered proprietor of this property. There is further email correspondence from the defendants referring to this as a form of security. The request for the plaintiff’s account details would appear to follow from an earlier email from the defendants recording that interest was to be paid monthly into the plaintiff’s nominated account. I am satisfied that this email, containing the defendants’ agreement to terms, records the defendants’ acceptance of terms proposed by the plaintiff. An agreement was made at this point. I am further satisfied from this evidence that the contract was made in New Zealand.

[19] It appears from the emails that at this time both defendants were in Fiji at least up to 10 September 2007. However, it also appears that at this time the first defendant’s residence was Auckland. I come to this conclusion having regard to the matters discussed in the next three paragraphs.

[20] The documents signed by the defendants (a separate one for each defendant, and described as a “guarantee”) have been put in evidence. Although described as guarantees, they are in their terms simple acknowledgements of debt from each of the defendants to the plaintiff. The terms and format of each document are as follows:

The Lender has agreed to lend to the Borrower who has promised to pay back the sum of NZ$500,000.00 (Five Hundred Thousand Dollars) cash together with interest at the rate of 24% per annum.

The Borrower shall pay the sum borrowed within 6 (six) months from the date of execution. In default the whole sum to be payable UPON DEMAND by the Lender.

[21] The documents record that each defendant signed the document at Suva on 7 September 2007. Signatures have been witnessed by a Commissioner for Oaths. The document signed by the first defendant records that her address at that date was 413/83 Halsey Street, Viaduct Harbour, Auckland, New Zealand. The address recorded in the document signed by the second defendant records an address in Suva. I am satisfied that the “personal guarantees” that the first defendant said had (4 See Burrows, Finn & Todd Law of Contract in New Zealand (3rd ed, LexisNexis, Wellington, 2007) at p 57, para 3.4 and p 65, para 3.4.7(b). been sent by fax to the plaintiff ’s loan consultant are these documents. It is sufficiently clear from the evidence that these documents were prepared by the defendants, both of whom are lawyers, or on their behalf. I am satisfied from this that at the date the agreement was made the first defendant was resident in Auckland. This is confirmed, if confirmation is required, by the email from the first defendant on 7 September in which she said she was returning to Auckland “next Friday” (see [15] above). In the context this meant returning to the place where she was then residing from Fiji, which she was simply visiting.

[22] Copies of the “guarantees” were produced by the plaintiff, as an annexure to her principal affidavit. The first defendant says in her first affidavit:

20. In support of her application Elaine [the plaintiff] has exhibited guarantee documents apparently executed in Fiji and subject to Fijian law. One is signed by me. I do not recall signing it, although the signature appears to be mine. At any hearing, I would ask the plaintiff to produce the original of these documents and the Commissioner for Oaths who has signed them

The second defendant, in her affidavit, says essentially the same thing:

6. … The signature appears to be mine but I do not recall signing it. At any hearing, I would ask the plaintiff to produce the original of this document and the Commissioner for Oaths who has signed it.

Having regard to the conclusions recorded above as to the origin of the documents, I regard this evidence as disingenuous, at the least

[23] The defendants advised that the loan was sought for a property investment in Fiji. At the request of the defendants the loan was to be advanced in three tranches to bank accounts in three different jurisdictions. An email from the second defendant to the plaintiff on 10 September contained the defendants’ directions in this regard.

(a) “$150,000FJD for value today to (approximately NZD$133,842.51)” to a Lloyds TSB account in the Isle of Man (united Kingdom)

(b) “$100,000FJD for value today to (approximately NZD$89,211.05)” to an ANZ bank account in Auckland.

(c) “Balance of the money (approximately NZD$276,946.44)” to an ANZ Bank account in Suva, being the trust account of Jamnadas & Associates.

[24] The loan was advanced in three tranches on 10 September 2007, subject to some reasonably small adjustments in the New Zealand dollar amounts for the first two tranches. The requested payment to the bank account in the Isle of Man could not be made in Fijian dollars. By agreement it was made in US dollars.

[25] The plaintiff says that the defendants have repaid a total of NZ$70,000 being one sum of NZ$30,000 in December 2007 and four payments of NZ$10,000 each in January, February, March and April 2008. The first defendant says that she made these payments in cash from “my funds in Fiji”.

The evidence as it stands establishes that all of these payments were made in New Zealand dollars and made in New Zealand.

[26] The first defendant says:

I do not accept the repayment sum Elaine states and believe that I have made more repayments than she has listed. By my calculations I estimate that I have cash repayments totalling more than $70,000.

However, she does not state the amount that she contends has been repaid

[27] There is a body of evidence, mainly copies of emails, relating to steps taken by the plaintiff from September 2008 to secure repayment, with responses from the defendants. The general tenor of the responses from the defendants through to around October 2009, when this correspondence appears to have ceased, is that the debt and interest would be repaid but the defendants were experiencing various difficulties. Advice from the defendants includes the following:

(a) On 16 September 2008 the plaintiff emailed the first defendant requesting repayment of the principal of NZ$500,000 and eight months interest. The first defendant’s responded on the same day and said: “I am arranging full repayment of the funds for both principal and interest for December 2008.”

(b) Email 6 October 2008; first defendant to the plaintiff:

… I am unable to be in Auckland in October but have made arrangements to be there for the repayment of the principal and interest in December. However, if you need the money urgently I can TT it to your account but as you know this is not the most desirable method of payment.

(c) Email 15 December 2008; first defendant to the plaintiff. This email records the following points of relevance to the question of jurisdiction: (1) a debt of NZ$580,000 was acknowledged; (2) payment in full was promised as soon as possible; (3) payment was to be made to the plaintiff in New Zealand; and (4) the difficulty in effecting payment was getting approval from the Fijian Reserve Bank.

(d) Email 20 January 2009; first defendant to the plaintiff, in response to an enquiry of the previous day from the plaintiff. The first defendant said that approval from the Fijian Reserve Bank was expected “soon” and “The caveat is in place for your security”.

(e) Email 6 April 2009; second defendant to the plaintiff:

I note your sentiments.

However, I require legal advise [sic] on this dealing. I have sent the information through to my solicitor in Auckland. I have followed up with him to give me a response so that I may respond to you. As soon as I have heard from him I will contact you as I am keen to bring this matter to a close.

(f) Email 17 April 2009; first defendant to the plaintiff:

I trust that you have been following the recent events in Fiji with regards to the political instability and civil unrest. The bottom line is that we are now under a military dictatorship and have just had our currency devalued by 20%. As a result, we are not in a position to give you a clear indication of a solution at this time.

(g) Email 23 April 2009; first defendant to the plaintiff following a pressing email from the plaintiff:

Everything discussed was dependent on a stable economy in Fiji including the funds I expected to be paid to New Zealand after may [sic].

FIJI COUP 2006

We effectively have just had another[r] coup and up until yesterday were without an executive, a judiciary etc.

I cannot begin to express how this affects us financially in terms of the currency devaluation and the limits on remittances. This was not something I foresaw. I do not have a clear position on a solution at this time but assure you I am doing everything in my ability to bring this to a close.

I request your continued patience at this EXTREMELY DIFFICULT TIME. Once things have stabilized and I have a clear solution I will call you. In the meantime, it serves neither of our purposes to be adversarial or antagonistic in order to reach a solution. I trust my position is clarified.

(h) Email 2 June 2009; first defendant to the plaintiff:

I write you this email as an update on the situation here in Fiji. Unfortunately, the situation with both the judiciary, the Reserve Bank and the financial sector remains unchanged. In reality, it is likely we will have a further currency devaluation and a complete moratorium on remittances overseas.

(i) Email 3 June 2009; first defendant to the plaintiff:

…

As previously discussed, you have a caveat for security over our family in Orakei [sic]. ... The property in Orakei is owned by my sister Renee who will not consent to a 2nd mortgage. I have previously outlined this to you. There is nothing more I can do in this respect.

We have sought advice from our lawyer in Auckland, and the only suggestion he has come up with is that we give you a property in Fiji in settlement of the debt. Please let us have your views on this as this is the only imminent solution available.

In the meantime, I will continue to apply myself in finding a solution. I appreciate your understanding of this matter at this hugely trying time.

…

(j) The final email along these lines was one of 9 October 2009 from the first defendant to the plaintiff.

[28] It appears that the plaintiff subsequently instructed a lawyer in Fiji to take steps on her behalf. The second defendant says that she received a call from a Suva lawyer “in late 2010 or mid-2011”, stating that he had been instructed to act for the plaintiff in relation to a loan. The second defendant says that she expected, following this discussion, to be served with proceedings issued in Fiji, but nothing occurred.

[29] The proceeding in this court was issued on 8 September 2011. The plaintiff sought summary judgment. The hearing date allocated for the summary judgment was 16 February 2012. The day before the hearing the first defendant filed her appearance protesting jurisdiction. She had been served in Fiji on 9 December 2011. The second defendant was subsequently served and filed her protest to jurisdiction.

[30] The Auckland property provided by the defendants as security is registered in the name of the second defendant. Title is subject to a mortgage. There have been defaults under this mortgage, with default notices issued by the mortgagee.

Discussion

[31] The plaintiff has established that the original leave to serve the proceeding on the defendants in Fiji was correctly granted. My reasons follow and with reference to the matters set out in paragraphs (a) to (c) of r 6.28(5).

[32] The claim has a clear and substantial connection with New Zealand. I am satisfied, on the evidence presently available, that the proper law of the contract is the law of New Zealand. There was no express agreement as to the applicable law. In the Conflict of Laws chapter in the Laws of New Zealand, at para 118, there is a list of 11 factors identified in decisions of New Zealand and English courts for determining the proper law when there is no express choice. Six factors favour New Zealand law as the proper law: New Zealand is the place where the contract was made; New Zealand is the place where the contract is to be performed; part of the subject matter of the contract (the security) is real property in New Zealand; payment is to be made in New Zealand dollars; there is a connection with a previous transaction fully conducted in New Zealand; on the basis of the defendants’ case the contract may be void or voidable under the Fiji Money Lenders Act, but there is no argument to similar effect under New Zealand law. Of the remaining five factors, three are neutral and two have no application. In addition, the defendants sought legal advice on the contract from a lawyer in New Zealand.

[33] The individual factors listed in respect of the proper law of the contract separately establish that the claim has a clear and substantial connection with New Zealand. In addition: the loan was designated in New Zealand dollars; it was repayable in New Zealand dollars; part of the loan was paid into a bank account in New Zealand; the real property provided as security is owned by the second defendant; and, on the evidence presently available, the first defendant was living in New Zealand when the contract was made.

[34] There is a serious issue to be tried on the merits. Having regard to the email correspondence set out above there is in fact a serious question as to whether the defendants have any defence. The defendants admitted liability and made numerous promises to repay the loan. The defendants now contend that the loan was subject to the Fiji Money Lenders Act. This contention was made more recently; that is to say, well after the correspondence up to October 2009 during which there were express acknowledgements of liability and numbers of promises of payment. These were express acknowledgements from Fijian lawyers. The relevance of the Fiji Money Lenders Act is further discussed below.

[35] The next question is whether New Zealand is the appropriate forum for the trial. Mr Hollyman, for the defendants, referred to the discussion of this topic by Lord Goff in Spiliada Maritime Corp v Cansulex Ltd: The Spiliada. 5 Lord Goff noted that, although the topic is often referred to by the Latin tags forum non conveniens or forum conveniens, the question is not one of convenience, but of the suitability or appropriateness of the relevant jurisdiction. This is in fact reflected in the rule itself which refers to “the appropriate forum”. The principles outlined by Lord Goff are summarised in McGechan on Procedure. Having regard to the principles summarised there, and allowing for the fact that in cases such as the Spiliada Maritime Corp v Cansulex Ltd: The Spiliada [1987] AC 460, [1986] 3 All ER 843 (HL) at

473-474, 853-854.

McGechan on Procedure (looseleaf ed, Brookers) at HR6.29.05. present the onus is on the plaintiff to establish that New Zealand is the appropriate forum (the onus being on the other party in cases such as The Spiliada), I am satisfied that New Zealand is the appropriate forum for the trial, rather than Fiji (Fiji being the only alternative proposed). In the interests of all parties and the ends of justice this claim may be tried more suitably in the New Zealand High Court. The plaintiff, for reasons already discussed, has founded a jurisdiction as of right in accordance with New Zealand law. Questions of comparative cost and convenience may marginally favour the defendants, because there are two defendants and only one plaintiff, but I do not regard this as a matter of particular weight in this case. The court in Fiji is not “clearly more appropriate for the trial” (the fourth factor from The Spiliada noted in McGechan).

[36] There are some further considerations. The defendants say they wish to call witnesses resident in Fiji. I am doubtful as to the stated need for this. The only issue raised by the defendants is the tentative question from each as to whether they signed the “guarantee”. I have already recorded my conclusion that this is, at best, disingenuous. There is the question as to the possible application of the Fiji Money Lenders Act. If the contract is entirely governed by the law of New Zealand, the Fiji Money Lenders Act may have no application at all. In any event, the questions that may arise in this regard do not make New Zealand an inappropriate forum for the trial. Questions as to the applicability of foreign statutes and, if they apply, their interpretation, readily arise in, and are determined in, New Zealand courts. The fact that the first and second defendants are domiciled in Fiji does not in this case, and perhaps does not generally, make New Zealand an inappropriate forum compared with Fiji.

[37] Another factor indicating that a court in Fiji would not be an appropriate forum – not in the interests of all of the parties and the ends of justice – is evidence suggesting that there could be some difficulties for the plaintiff in seeking to conduct court proceedings in Fiji or, if proceedings are successfully brought, in enforcing a judgment to secure payment to the plaintiff in New Zealand. Some of the emails from the defendants themselves indicate that there could be some difficulties for the plaintiff in proceeding in Fiji or in securing payment following judgment. There is further evidence, produced in an affidavit for the plaintiff, arising from a report by The Law Society Charity, a society established by the Law Society of England and Wales. This is a report dated January 2012. For reasons set out in the report, there are conclusions including the following: the rule of law no longer operates in Fiji; the independence of the judiciary cannot be relied on; Government controls and restrictions make it virtually impossible for an independent legal profession to function appropriately. This court expresses no conclusions as to the accuracy of this report. It would not be appropriate to do so. In addition, the report is not concerned in any direct way with private proceedings between individuals for the enforcement of contracts. These matters are nevertheless relevant on the question as to the appropriate forum and support the conclusion that the plaintiff has established that New Zealand is the appropriate forum for this proceeding.

[38] New Zealand is also an appropriate forum because of the security over land in New Zealand. The proceeding has not been issued to enforce the security. However, if the plaintiff succeeds, the contract will have been sustained and the plaintiff will be entitled to enforce what the defendants expressly referred to as security over the land in New Zealand. On the face of the contract, including the “guarantee” drafted by the defendants, the plaintiff is entitled to proceed with an action in New Zealand as the first step to enforce the security in New Zealand granted by the defendants. Proceeding with the first step through the court in Fiji makes the Fijian court an inappropriate forum for this further reason.

[39] Paragraph (d) of r 6.28(5) refers to any other relevant circumstances which may support an assumption of jurisdiction by the New Zealand court. It is unnecessary to discuss any additional factors which might come under this heading.

Result

[40] There are the following orders:

(a) The defendants’ applications under rr 5.49 and 6.29 are dismissed and their appearances under protest to jurisdiction are set aside.

(b) If the defendants, or either of them, wish to oppose the plaintiff’s application for summary judgment, a notice of opposition and any affidavit setting out the defence is to be filed and served on or before Friday, 22 June 2012. For the purpose of complying with this order, copies of signed documents, including sworn affidavits, may be filed to comply with the timetable provided the originals are filed promptly after 22 June 2012.

(c) If the defendants, or either of them, wish to file a statement of defence, the statement of defence is to be filed and served by 22 June 2012.

(d) Any affidavit in reply, pursuant to r 12.11, by or on behalf of the plaintiff, is to be filed and served by 29 June 2012.

(e) The application for summary judgment will be heard on 3 July 2012 at 10:00 am.

[41] If the plaintiff wishes to proceed with her application for a freezing order, as sought in the without notice application dated 19 March 2012, or otherwise, such an application is to proceed on notice and the following further orders apply:

(a) The plaintiff’s application and all supporting documents are to be filed and served by Wednesday, 13 June 2012.

(b) Any notice of opposition and supporting affidavits for the defendants are to be filed and served by 22 June 2012. Copies of signed documents, including sworn affidavits, may be filed to comply with the timetable provided the originals are filed promptly after 22 June 2012.

(c) Any affidavits in reply for the plaintiff are to be filed and served by 29 June 2012.

(d) The application for the freezing order will be heard in conjunction with the application for summary judgment on 3 July 2012 at 10:00 am.

[42] The plaintiff is entitled to costs on a 2B basis on the defendants’ applications under rr 5.49 and 6.20 together with costs on the appearance on 16 February 2012 in support of the summary judgment application. Costs are to be on a 2B basis. Questions of all other costs are reserved.

Woodhouse J

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND AUCKLAND REGISTRY

CIV-2011-404-005601 [2012] NZHC 1698

BETWEEN ELAINE CATHARINA BELL Plaintiff

AND RAINA LAL First Defendant

AND RENEE DEVINA SINA LAL Second Defendant

Hearing: 3 July 2012

Appearances: E St John for Plaintiff

K M Quinn for First and Second Defendants

Judgment: 13 July 2012

JUDGMENT OF GODDARD J

This judgment was delivered by Justice Goddard on 13 July 2012 at 5.30 p.m., pursuant to r 11.5 of the High Court Rules

BELL V LAL HC AK CIV-2011-404-005601 [13 July 2012]

[1] Before the Court are three applications: an application for summary judgment and an application for a freezing order, both filed by the plaintiff; and an application by the defendants to stay a judgment of Woodhouse J delivered on 7 June 2012, dismissing the defendants’ protest to jurisdiction.[1]

[2] In logical order of sequence the argument in support of the application for a stay of Woodhouse J’s judgment relating to jurisdiction proceeded first and occupied the bulk of hearing time.

[3] The background to all three applications is a claim for debt by the plaintiff in the sum of $430,000 plus interest. This comprises the balance owing on a loan of $500,000 the plaintiff made to the defendants in September 2007. The history of that loan, as set out by the plaintiff in her affidavit evidence and as evidenced in email and other forms of communication between the plaintiff and the first and second defendants, was traversed in detail by Woodhouse J in his judgment. It is unnecessary to retraverse that same history in extenso here. It will suffice to briefly set out the matters of significance that are detailed in the judgment:

A “Final agreement” between the parties was recorded in an email of 10 September 2007 to the plaintiff from the second defendant on behalf of both defendants. This set out the terms of the loan agreement, which was to be for 3 months at an interest rate of 24 per cent per annum. The security for the loan was stated in the agreement as:

Caveat over 7 Awarua Crescent, Orakei (we will cover your solicitor’s costs for this)

Personal Guarantees by both Raina & Renee Lal

Both defendants were in Fiji at the time of signing the agreement. However, the first defendant’s residence was in Auckland.

Each defendant also signed a personal guarantee, expressly acknowledging the loan in the following terms:

The lender has agreed to lend to the Borrower who has promised to pay back the sum of NZ$500,000.00 (Five Hundred Thousand Dollars) cash together with interest at the rate of 24% per annum.

The Borrower shall pay the sum borrowed within 6 (six) months from the date of execution. In default the whole sum to be payable UPON DEMAND by the lender.

Woodhouse J noted that these guarantees were signed on 7 September 2007 and witnessed by a Commissioner of Oaths. The guarantee signed by the first defendant again recorded her address as Auckland, New Zealand.

Woodhouse J noted that the guarantee documents were prepared by the defendants, both of whom are lawyers, or on their behalf, and that evidence proffered in February 2012 by the defendants in protest of jurisdiction - that they could not by that stage recall signing the guarantees - was “disingenuous at the least”.

The loan money was advanced in three tranches to bank accounts in three different jurisdictions, one of those being New Zealand.

Some repayment and interest payments were made in December 2007 and through early 2008. All of these payments were in New Zealand dollars and were made in New Zealand.

Between September 2008 and October 2009 a series of emails was exchanged between the plaintiff and the defendants, in which the defendants proffered various reasons for their inability to repay the debt during that period. These included the unstable political situation and state of the economy in Fiji. In all of these e-mails the defendants sought further time to pay. The emails contain numerous actual or implied acknowledgements of the debt as owing, and also make reference to the caveat for security over the family property in Orakei, Auckland.

The second defendant did not make herself available to be served with the plaintiff’s summary judgment application until after an order for substituted service was made. She was subsequently served in Fiji. The first defendant was served in Fiji on 9 December 2011. Woodhouse J was satisfied that the plaintiff had established that leave to serve the proceeding on both defendants in Fiji was correctly granted.

[4] Having traversed the evidence with a considerable degree of care, Woodhouse J was satisfied that the plaintiff ’s claim “has a clear and substantial connection with New Zealand” and “that the proper law of the contract is the law of New Zealand”. He found that six of the 11 factors, identified in decisions of New Zealand and English courts for determining the applicable law when there is no express choice, favoured New Zealand as the proper legal forum. The following extracts are relevant:

[32] ... New Zealand is the place where the contract was made; New Zealand is the place where the contract is to be performed; part of the subject matter of the contract (the security) is real property in New Zealand; payment is to be made in New Zealand dollars; there is a connection with a previous transaction fully conducted in New Zealand; on the basis of the defendants’ case the contract may be void or voidable under the Fiji Money Lenders Act, but there is no argument to similar effect under New Zealand law

..

[33] ... the loan was designated in New Zealand dollars; it was repayable in New Zealand dollars; part of the loan was paid into a bank account in New Zealand; the real property provided as security is owned by the second defendant; and ... the first defendant was living in New Zealand when the contract was made.

[5] For all of the above reasons Woodhouse J was able to conclude that the plaintiff had discharged the onus on her to establish New Zealand as the appropriate forum (based on suitability or appropriateness of the jurisdiction rather than convenience) and that she had founded a jurisdiction as of right in accordance with New Zealand law. The only alleged need to call evidence from any witnesses who might be resident in Fiji arose from the “disingenuous” issue tentatively raised by the defendants as to whether each of them had in fact signed the “guarantees”.

[6] The defendants’ applications under rr 5.49 and 6.29 were dismissed and their appearances under protest to jurisdiction set aside. Then followed a series of timetable orders, including an order that any notice of opposition and affidavits setting out a defence to the summary judgment application were to be filed and served on or before 22 June 2012; and an order that the application for summary judgment would be heard today, 3 July 2012.

[7] The defendants subsequently retained and instructed new solicitors and counsel.

[8] On 22 June 2012, the date appointed for the filing of any notice of opposition to the entry of summary judgment, the defendants chose instead to file an appeal against the judgment of Woodhouse J and sought an application for stay of proceedings in this Court.

Argument in support of stay of proceedings

[9] In support of the application for a stay of proceedings, pending determination of the appeal, four essential grounds were advanced on behalf of the defendants. Relying on the list of factors to be taken into account for stay applications, as set out by the Court of Appeal in Keung v GBR Investment Ltd,[2] Mr Quinn identified the following four factors as relevant and applicable:

Refusal of the stay would place the defendants in an invidious position of having to either take a step in the proceeding by filing late papers in opposition to summary judgment; or alternatively by allowing summary judgment to be entered against them. If summary judgment were entered against them, their protest to jurisdiction would become irrelevant. Mr Quinn relied on the decision of the Court of Appeal in Advanced Cardiovascular Systems Inc v Universal Specialties Ltd[3] as authority for the proposition that it would be a procedural error to allow the summary judgment application to go to a hearing “before the initial question of jurisdiction is determined”. For this Court to entertain the summary judgment application and refuse the stay would render nugatory the defendants’ appeal against the setting aside of their protest in jurisdiction. It would force the defendants either to accept the jurisdiction of the New Zealand Court, or to accept that final judgment would be entered against them. In either case their appeal would become pointless.

The second ground was directed to the bona fides of the appeal. In support of this, Mr Quinn referred to the grounds set out in the notice of appeal, submitting that the appeal is based on a serious point of law and is meritorious; that it is not simply an appeal against findings of fact. In terms of the factual issues arising, he pointed to the fact that the guarantee documents were executed in Fiji; that the money was loaned to Fijian citizens; and that one of the tranches of money advanced was in Fijian dollars for investment in Fiji.

The third ground of argument was lack of prejudice to the plaintiff from the granting of a stay. Mr Quinn pointed out that the plaintiff’s claim is for a liquidated sum, with interest continuing to accrue at 24 per cent. (In relation to that point, however, it is appropriate to record here that the plaintiff has, in fact, received no interest since 2007, let alone repayment of principal).

Mr Quinn submitted that, as Woodhouse J had noted at [32] of his judgment, the loan agreement may be void or voidable under the Fiji Money Lenders Act, chapter 234 of the Laws of Fiji. He suggested that possibility provided ample explanation for the defendants to seek an appeal and an absence of reason to assume that the appeal is not bona fide.

The next ground advanced in support of a stay of proceedings was that no delay would arise as a result of the stay - the plaintiff’s claim being for a liquidated sum, with interest continuing to accrue at 24 per cent. Further, as the plaintiff did not commence the claim proceeding until late 2011, it is incongruous for her to complain about delay.

The next ground in support of a stay was the overall balance of convenience.

Under this head Mr Quinn argued that, as there has been no substantive judgment entered in this case, there are no fruits of a judgment of which the plaintiff is being deprived. In contrast, the defendants have a position that needs to be preserved, in case their appeal is successful. The proceedings in the present case are still at an interlocutory stage. Thus, if a stay is not granted and the defendants’ appeal ultimately succeeds, the damage and inconvenience to them will be considerable. Mr Quinn submitted that by the time the appeal is heard the plaintiff will have obtained judgment essentially by default and will have become entitled to execute the judgment. By contrast, if a stay were granted and the appeal ultimately fails the plaintiff is able immediately to pursue her summary judgment application, so is not inconvenienced.

Discussion

[10] Notwithstanding, Mr Quinn’s careful and well presented arguments I am not persuaded that the discretion of the Court should be exercised in favour of a grant of stay in this matter.

[11] The defendants have defaulted on their obligations under this short-term loan, due to have been repaid in December 2007, since at least early 2008. No principal or interest has been paid since at least early 2008.

[12] The implication (and it is no more than that) that the debt may belatedly be contested has not been frankly notified to date by the filing of a notice of opposition to the plaintiff’s application for summary judgment.

[13] The implication that there may be a contest about whether the debt is owing comes very late in the five year history of the transaction between the parties. Furthermore, the filing of the appeal and the steps now being taken by the defendants come late in the course of this proceeding and reflect to a degree on the bona fides of their intentions and approach.

[14] The defendants were ordered to file any notice of opposition and affidavits in support by 22 June 2012. They did not do so but instead elected to file an appeal in relation to the jurisdiction issue. While they were entitled to take that step and thus elect not to comply with the timetable order for opposing the entry of summary judgment, they nevertheless remain in a situation where there is no formal contest to the plaintiff’s claim that a debt has been owing to her since 2007.

[15] There has been no repudiation of the many actual and implied acknowledgements of the debt as being due and owing evident in the exchange of emails between September 2008 and October 2009. These set out numerous reasons as to why the debt was not able to be repaid during that period. All that was being put forward were reasons why it could not be repaid at that time. The onus was on the defendants to either repay the debt or repudiate it; or to at least continue paying interest at the rate agreed while the debt remained outstanding.

[16] The challenge to the jurisdiction of the New Zealand courts and the raising of the possible application of the Fiji Money Lenders Act comes very late in the history of the transaction and at a late stage of these proceedings. That is not to determine them as having no validity but the lateness of their being raised is a factor to consider in the exercise of discretion to grant a stay.

[17] While it is not for this Court to make observations on the likely outcome of the defendants’ appeal, the appeal lacks apparent strength in light of the history of the transaction and the numerous evidential factors favouring the jurisdiction of the New Zealand courts.

[18] The plaintiff has now been kept out of her entitlement to her money for an unconscionably long period, without the furnishing of any substantive defence.

[19] Since proceedings were issued the defendants have not offered to pay any money into court. In contrast, the plaintiff has given an undertaking as to damages in relation to her application for a freezing order over the Orakei property.

[20] Taking all of the above into account, I am satisfied this Court should not exercise its discretion in favour of a stay of the plaintiff’s summary judgment, pending disposition of the defendants’ appeal on the jurisdiction point. This will not necessarily render the defendants’ appeal nugatory, as the making of new timetable orders in relation to the summary judgment have been discussed with counsel and will be made at the conclusion of this judgment. It will be for the defendants to expedite the determination of their appeal and the filing of any opposition to summary judgment.

Application for freezing order

[21] There has been no further reduction in the debt nor interest paid on the outstanding amount since early 2008, more than four years ago.

[22] The security for the debt is over a property owned by a family member of the defendants, located at 7 Awarua Crescent, Orakei, Auckland.

[23] There is a caveat over that property by way of security. This was recorded in the “Final agreement”, together with an undertaking by the defendants to cover the plaintiff’s solicitor’s costs in connection with lodging the caveat.

[24] Affidavit evidence filed the day before this hearing, Monday 12 July 2012, establishes there have been mortgage arrears on the secured property and that there was an indication of intention by the mortgagee to have proceeded to a mortgagee sale. An email letter from the credit controller of the mortgagee informs that, only as late as 2 July, the loan arrears were paid and there is a current credit, and that a monthly automatic payment has now been set up to pay future loan instalments. The letter ends with the advice “At this time we will not be proceeding to a mortgagee sale”.

[25] The above history, together with the recent indication that a mortgagee sale of the property was contemplated, both favour the granting of the freezing order sought by the plaintiff, in order to preserve her position pending disposition of the summary judgment.

[26] Woodhouse J referred to the importance of the security over the property in realising the plaintiff’s contractual rights. He stated:

[38] ... The proceeding has not been issued to enforce the security. However, if the plaintiff succeeds, the contract will have been sustained and the plaintiff will be entitled to enforce what the defendants expressly referred to as security over the land in New Zealand.

The application for summary judgment

[27] In light of the decision I have reached in relation to the applications for a stay and for a freezing order, I deem it prudent to permit the defendants one further opportunity to decide if they wish to oppose the entry of summary judgment. I am not, therefore, prepared to enter judgment at this time. Thus the course I am adopting does not force the defendants into an invidious position. They are at liberty to seek a fast track hearing for their appeal already filed and they should seek to have that determined prior to 8 August 2012, when the application for summary judgment will be heard in this Court at 10:00 a.m.

Result

[28] The defendants’ application for a stay of Woodhouse J’s judgment of 7 June 2012 is dismissed.

[29] The plaintiff ’s application for a freezing order over the property at 7 Awarua Crescent, Orakei, Auckland is granted.

[30] The freezing order restrains the second defendant from removing the asset that is the property at 7 Awarua Crescent, Orakei, Auckland, or from disposing, dealing with, or diminishing the value of that asset, including but not limited to mortgaging the asset.

[31] The freezing order remains in force until further order of the Court.

[32] The plaintiff’s summary judgment application is adjourned until Wednesday 8 August 2012.

[33] Any notice of opposition and any affidavit in support setting out the defence is to be filed and served on or before Wednesday 25 July.

[34] Any statement of defence is to be filed and served by Wednesday 25 July and any affidavit in reply by or on behalf of the plaintiff is to be filed and served by Wednesday 1 August.

Costs

[35] Costs on a 2B basis are reserved.

Lautoka High Court

Lautoka High Court AT LAUTOKA

[CIVIL JURISDICTION]

CIVIL CASE NO: ACTION 18 OF 2013

IN THE MATTER of the Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act.

AND IN THE MATTER of a Judgment of the High Court of New Zealand obtained in Elaine Catherine Bell v Raina Lal and Renne Devina Sina Lal Civ: 2011-404-005601, [2012] NZHC 1993 dated the 8th day of August 2012.

BETWEEN:

ELAINE CATHERINE BELL

of 66 Wanganui Avenue, Ponsonby,

Auckland, New Zealand, Airline Concierge.

APPLICANT/JUDGMENT-CREDITOR

AND:

RAINA LAL

of 8 Bryan Road, Nadi, Fiji, Legal Practitioner.

1ST JUDGMENT-DEBTOR

AND:

RENEE DEVINA SINA LAL

of 73 Naivurevure Road, NLTB

Subdivision, Tamavua, Fiji, Legal Practitioner.

2ND JUDGMENT-DEBTOR

Ex-parte

Counsel

Ms Virisila Lidise for the Applicant/Judgment-Creditor

Date of Hearing : 20 February 2013

Date of Ruling : 25 February 2013

RULING

1. This is an application for registration of a Judgment delivered by the High Court of New Zealand in Auckland in Case No CIV-2011-404-005601 [2012] NZHC 1993 in the High Court of Fiji, Fiji.

2. The Judgment was resulted from the proceedings had between Elaine Catherine Bell, the plaintiff, on one part and Raina Lal and Renee Devina Sina Lal, the defendants, on the other. Mr Justice Duffy of the High Court of New Zealand in Auckland, in his Judgment dated 08 August 2012, set-out reasons for the award of a sum of NZ $1,007,247.14 in favour of the plaintiff. Costs, too, have been awarded in a sum of NZ $ 21, 142.30 according to the Order sealed on 08 August 2012 by the Registry of the High Court of New Zealand in Auckland.

3. The application for registration of the Judgment in the High Court of Fiji in Lautoka has been made by way of summons supported by an affidavit dated 06 February 2013 deposed to by Mr Kamal Kumar, Legal Practitioner, on instructions received from Messrs Eugene St. John on behalf of the applicant/Judgment-Creditor-Elaine Catharine Bell, under Sections 3 and 7 of the Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act [Cap. 39] (the Act) read with the Rules made by the Hon. Chief Justice under Section 6 of the Act.

4. Section 3 of the Act provides:

(1) Where a judgment has been obtained in the High Court in England or Ireland or in the Court of Session in Scotland the judgment creditor may apply to the Supreme Court in Fiji at any time within twelve months after the date of the judgment or such longer period as may be allowed by the said Supreme Court to have the judgment registered in the said Supreme Court and on any such application the said Supreme Court may, if in all the circumstances of the case it thinks it just and convenient that the judgment should be enforced in Fiji, and subject to the provisions of this section, order the judgment to be registered accordingly.

5. Application of the provisions of the Act, including those of Section 3 (1) above, has been extended to encompass a 'superior court' of other designated countries by Orders of the Governor-in-Council. New Zealand has been such a designated country of which Judgments of a 'superior court' of that country could be recognized for registration in the High Court of Fiji from 10 July 1925 under Section 7 (1) of the Act.

6. Section 7 (1) of the Act provides that:

Where the Governor-General is satisfied that reciprocal provisions have been made by the legislature of any other country or territory of the Commonwealth outside the United Kingdom for the enforcement within such country or territory of judgments obtained in the Supreme Court of Fiji the Governor-General may by order declare that this Act shall extend to judgments obtained in a superior court in that country or territory in like manner as it extends to judgments obtained in a superior court in the United Kingdom and on any such order being made this Act shall extend accordingly.

7. I have considered the summons and the contents of the supporting affidavit. I am convinced that the High Court of New Zealand is a 'superior court' within the meaning of Section 7 of the Act. In this regard, I also place reliance on the judgments of this court in the cases of Jones and Tozer v Mathieson [1990] 36 FLR 116 and Jones v Chatfield [1991] FJHC 42, where authoritative pronouncements were made to the effect that the High Court of New Zealand was superior court for the purposes of the Act.

8. Provisions of Section 3 (2) of the Act mandate this court to consider whether the registration of a judgment of a superior court of such a designated country could be excluded by the criteria set-out in that section.

9. Section 3 (2) provides that:

No judgment shall be ordered to be registered under this section if-

(a) the original court acted without jurisdiction; or

(b) the judgment debtor being a person who was neither carrying on business nor ordinarily resident within the jurisdiction of the original court did not voluntarily appear or otherwise submit or agree to submit to the jurisdiction of that court; or

(c) the judgment debtor being the defendant in the proceedings was not duly served with the process of the original court and did not appear notwithstanding that he was ordinarily resident or was carrying on business within the jurisdiction of that court or agreed to submit to the jurisdiction of that court; or

(d) the judgment was obtained by fraud; or

(e) the judgment debtor satisfies the registering court either that an appeal is pending or that he is entitled and intends to appeal against the judgment; or

(f) the judgment was in respect of a cause of action which for reasons of public policy or for some other similar reason could not have been entertained by the registering court.

10. I have considered the authenticated sealed order of the High Court of New Zealand in Auckland dated 08 August 2012 and a copy of the judgment of Mr Justice Duffy. There does not seem to be material to conclude that the Judgment sought to be registered by the applicant/Judgment-Creditor falls within any of the criteria set-out in Section 3 (2) of the Act; and/or, that the judgment has been satisfied by the Judgment-Debtor who appears to be currently resident in Fiji after submitting to the proceedings before the High Court of New Zealand.

11. I, accordingly, allow the summons dated 12 February 2013 of the applicant/Judgment- Creditor and grant leave for registration in this court of the Judgment in Elaine Bell v Raina Lal and Renee Devina Sina Lala CIV: 2011-404-5601 of the High Court of New Zealand in Auckland.

12. The applicant is directed to serve a copy of this order on the Judgment-Debtor as provided under the rules made under Section 6 of the Act forthwith. The Judgment-Debtor shall be entitled to apply for setting-aside of the registration of the Judgment not later than 15 April 2013.

13. Orders, accordingly. Costs of this application shall be in the cause.

Priyantha Nāwāna

Judge

High Court

Lautoka

Republic of Fiji Islands

25 February 2013