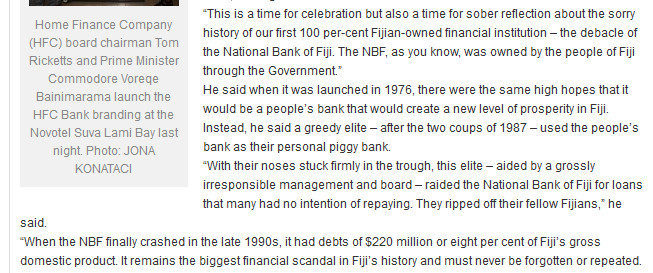

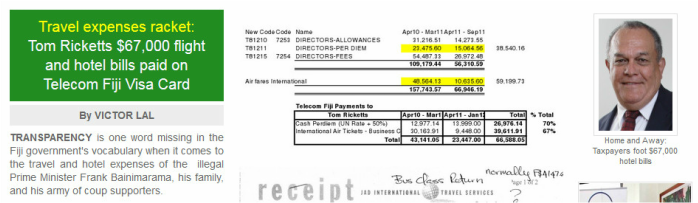

Home Finance Company (HFC) new National Bank of Fiji (NBF) In Waiting? COMING SOON: A Victor Lal Investigation - Last Friday Aiyaz Khaiyum applied to HFC Bank for refinancing his housing loan and bank approved the same day - all his loans from Colonial transferred to HFC; other Regime Ministers/Army Officers/Businessmen in |

Brigadier-General Aziz obtained multiple loans including $400,000 insurance payout for house burnt at Duncan Rd; Minister Natuva

raided HFC for Waila property and other residential properties

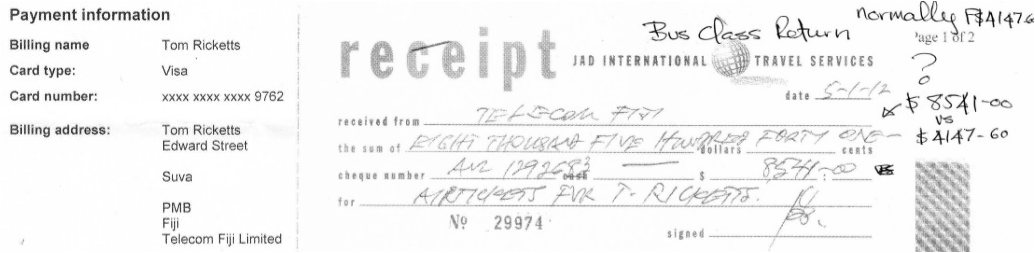

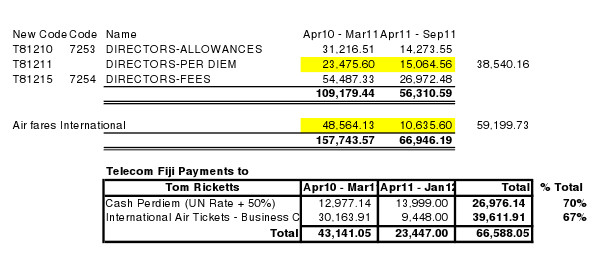

Home Finance Company (HFC) Board Chairman Tom Ricketts mirror-image of the NBF defaulters/elites Bainimarama was warning Fiji:

CJ Anthony Gates, brother Faizal Koya

CJ Anthony Gates, brother Faizal Koya and Nazhat Shameem

The Alliance Party, led by Mara, easily won 33 out of the 52 seats in Parliament: the NFP won 19 seats. By the time of the 1972 general elections, communal polarization between the different racial groups was complete. Mara, claiming to represent the i-taukei, and by now securely ensconced in power, immediately set about trying to consolidate his hold of the country.

The Mara-Koya rift publicly widened when Koya was denied the Prime Ministership on 7 April 1977 despite winning a razor-edge majoritTy of 26 seats in the first of the two general elections in that year. The politically bruised and battered Koya claimed that the Governor-General Ratu Sir George Cakobau’s decision to re-appoint Mara to head an Alliance minority government had ‘eroded and devalued democracy’, and he accused the Alliance Party of creating an ‘alarming situation’.

The personal conflict reached its climax when Koya deliberating whipped up Indo-Fijian sympathy by charging that Mara’s and the Alliance’s acceptance to form a minority government was because they did not want an Indo-Fijian Prime Minister in Fiji. He said their decision was an ‘insult to the Indo-Fijian community and its self-respect’.

Ratu Mara, in response, invoked culture, and presented his acceptance of the office as being the act of a subordinate chief with a duty of obedience: ‘I obeyed the command of His Excellency the Governor-General, the highest authority in the land and my paramount chief. I obeyed him in the same manner that thousands of Fijians obeyed their chiefs when they were called to arms – without question and with the will to sacrifice and serve.’

After that political debacle Koya’s political fortunes never recovered, and he finally resigned his leadership of the NFP shortly before the 1987 general election. He died in April 1993, leaving behind his widow Mrs Amina Begum Koya, and three children, daughter Shenaaz and sons Faiyaz and Faizal. His widow subsequently became the executrix of Siddiq Koya’s estate.

Chief Justice Anthony Gates and Koya and Company

In 1993 Mrs Koya approached Anthony Gates, who was now working for the Commonwealth DPP’s Office in Brisbane, Australia, to return to Fiji and take over the practise of Koya and Company, which he duly agreed. Gates was no stranger to Fiji’s judicial world. He first took up appointment as Crown prosecutor in the office of the DPP in 1977. He became the Deputy DPP in 1981 and a resident magistrate in 1985.

The Sitiveni Rabuka regime dismissed him as a magistrate when he refused to take a fresh oath of office to the coupist Rabuka and his co-conspiratorial overlords Mara and Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, president and prime minister respectively. Gates was appointed by the FLP to the Fiji High Court in November 1999.

But he surprised and disappointed a large band of his admirers (who admired him for his famous decision in the Chandrika Prasad case in which he had held that the 1997 Constitution had not been abrogated by the military intervention of Bainimarama to end the Speight coup, and that the Constitution continued to be the law of the land) when he became acting Chief Justice in April 2007 after the Bainimarama coup of 2006, and later as now the Chief Justice of Fiji.

However, a year after returning to Fiji in 1993,Gates found himself explaining his involvement in the law firm of Koya and Company when Mrs Koya was charged, convicted and imprisoned for arson. She was found guilty of “wilfully and unlawfully setting fire to the office of Messrs Koya and Company situated in the Popular Building, Vidilo Street, Lautoka on 23 March 1994”. She had set fire to the building in an insurance fraud to recoup business losses. It must be categorically stressed that Gates had no role in the insurance fraud nor was involved with Mrs Koya in setting fire to the Lautoka office. She had acted alone in the arson.

The Fiji Court of Appeal heard from the son of one of the owners of Popular Building, Mohammed Janif, who gave evidence that the Lautoka office had been let to Koya & Company for some years. By late 1993 the rent was seriously in arrears. Mrs Koya had been supervising the firm’s Lautoka office since Koya’s death. It had been agreed that the firm should vacate the office on 31 March 1994.

Gates gave evidence that in July 1993 after Koya’s death Mrs Koya asked him to come to Fiji and take over the practice. It was agreed that he should take over only the firm’s Suva office; Mrs Koya wanted to keep the Lautoka office operating for her sons (Faiyaz and Faizal) and to practice there when they qualified and tried to find a solicitor to take over Koya’s Lautoka practice on a temporary basis. She was unable to do so and, Gates said, he agreed in November 1993 to take over all professional and financial responsibilities for the Lautoka office.

The agreement provided for him to purchase for $7500 the whole practice of the late Koya together with his law books, furniture, office equipment, etc. However, under the agreement Mrs Koya was entitled, on giving three months’ notice within five years, to have the practice handed over by Gates to her sons together with the law books, furniture, office equipment etc.

As the law required that there be a barrister and solicitor in each of the Suva and Lautoka offices daily, Gates tried to find one to be employed in Lautoka. He was unsuccessful. He attended at the Lautoka office himself about two days a fortnight, he said, but that was not proper compliance with the law. He, therefore, informed Mrs Koya in February 1994 that the office might have to close at the end of that month. The decision was shelved until March, when he discovered that the landlord had sent a bailiff to levy distress because the rent was seriously in arrears. He arranged with the landlord to pay all the rent from the time he had taken over the practice and did so.

The Lautoka office of the practice not only was not staffed daily by a barrister and solicitor but also was being operated at a loss. Gates gave evidence that he was not willing to continue keeping it open. He had kept it open only to try to assist Mrs Koya to have a practice for her sons to operate when they qualified. He gave the landlord notice that the firm would vacate the office on 31 March 1994. He arranged with Nadan, a clerk in the firm, to have a “closing down” meeting with him and Mrs Koya on 24 March. He informed Mrs Koya of the meeting, he said.

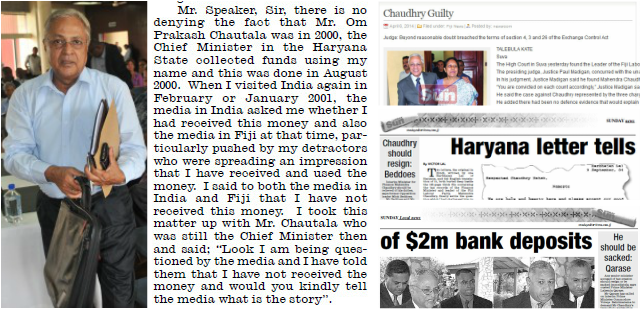

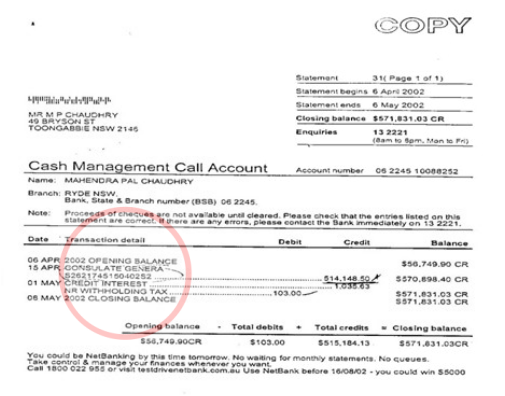

However, Nadan gave evidence that on 23 March Mrs Koya told him that she was going to Suva next day to conduct some other business with a Mr Mahendra Chaudhary (FLP leader and later Bainimarama’s former illegal Finance Minister who was caught hiding $2million in a secret Australian bank account which he had got from India for the poor Indo-Fijians). Nadan said that Chaudhary was overseas and that he told Mrs Koya so. The packing and moving out was to begin on that day.

After the fire, Gates said, Mrs Koya wished to complete the insurance claim but he considered that as principal of the firm, he should make the claim. If the claim had been met, he said, he would have paid to Mrs Koya the amount recovered less the expenses he had incurred in paying the arrears of rent and discharging the debt owed to the insurer, which had to be paid before it would deal with the claim.

In the end the Fiji Court of Appeal upheld the three year sentence imposed on Mrs Koya. She appealed to the Supreme Court (with Nazhat Shameem representing the State) which reduced the sentence to two years because of Mrs Koya’s age. The court maintained that there was evidence of careful planning on Mrs Koya’s part and the loss suffered was $90,000.

The motive was gain. In convicting Mrs Koya, Justice Lyons in the High Court in Lautoka had earlier stated that it was committed for the financial benefit of herself and her family; that she embarked on a scheme of deception involving others in order to deflect suspicion from her; that she intended the fire to go beyond the Koya premises by spreading kerosene along the passage; and that she put the businesses and livelihoods of other tenants in the building at risk and betrayed the respect and trust in which they held her.

On the positive side Justice Lyons had referred to Mrs Koya’s otherwise excellent character and her long history of involvement in community and religious affairs together with the assistance she had given to others less fortunate than herself. Other matters he saw as weighing heavily in her favour were the support she had given her husband in his law practice over many years and the way she had discharged her family responsibilities.

But Justice Lyons rightly stressed the seriousness of arson, emphasising that the Court must ensure that its sentence delivered the right message to the community by marking its condemnation of such conduct and acting as a deterrent to others.

Against these considerations Justice Lyons sought to balance what he called Mrs Koya’s “personal unique requirements”. These were primarily her age and state of health. She was born on 20 June 1930 and was 66 at the time of sentencing. A medical report of 14 May 1996 (a month before the NBF Debtors List was printed in the media) described her as suffering from undiagnosed abdominal pains, hypertension and depression for which she was under medication. There was, however, no medical evidence indicating that a prison term was likely to affect her expectation of life or her ability to serve a 3-year sentence.

Justice Lyons also took into account the stress to which she would have been subject from the time of Koya’s death in April 1993, when she attempted to keep his practice intact for their two sons. In dismissing the appeal against conviction and sentence, Justice Maurice Casey in the Fiji Court of Appeal stated: “It failed within 12 months, and it can be accepted that the prospect of losing the benefit of all the work she had put into it must have affected her judgment and driven her to this uncharacteristic act of criminal folly. Regrettably, of course, she is not the only person who has resorted to fire insurance fraud to recoup business losses.”

During her trial, a former employee of an insurance company gave evidence that early in November 1993 Mrs Koya renewed the insurance of the contents of the office, the insurance having lapsed in 1992. The amount of the cover was $100,000. After payment of $1573.05 by Mrs Koya on 4 November 1993, the firm still owed the insurer $5962.55. The witness also gave evidence that on 21 March 1994, two days before the fire, Mrs Koya called on him to seek confirmation that, despite the indebtedness, the policy was still in force. He confirmed that and, in response to her inquiry, told her that the amount of the cover was $100,000.

Mrs Koya had persisted in maintaining her innocence, to quote Justice Casey ‘despite what can only be described as an overwhelming circumstantial case against her, reflected in the fact that the assessors took only 15 minutes to reach their verdicts. The lack of a responsible acknowledgement of guilt - or indeed of any expression of remorse for her conduct - precluded the Court from reducing her sentence to reflect such an attitude’.

Faizal Koya: Bainimarama’s magistrate

In a cruel twist of co-incidence (or prior arrangement) both Gates and Faizal Koya (also Speaker of the Fiji Muslim League) saw their paths cross once again following the Revocation of Judicial Appointments Decree. On 20 April 2009 Faizal Koya, 10 days after the abrogation of the 1997 Constitution, was suddenly appointed one of nine magistrates, and a month later, on 22 May 2009 Gates, from his father’s old law firm of Koya and Company, took oath of allegiance as the new Chief Justice of Fiji.

Anthony Gates taking oath as Chief Justice in May 2009

In accepting the Chief Justice’s post Gates said he his colleagues accepted their appointment to the bench because they did not want a repeat of 1987. Having served as a judicial officer through all of Fiji’s five coups, Gates claimed that from such efforts would emerge a truly independent judiciary and in time a closer approximation to the Rule of Law than Fiji has had in 20 years or more.

Mrs Amina Koya Begum and National Bank of Fiji Loan

On 4 January 2010, Mrs Koya was laid to rest by close family and friends in Lautoka. In his eulogy the Attorney General and Minister for Justice Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum said Mrs Koya was indeed a tower of strength to all who knew her: “There is indeed a time for everything – you come to this earth with nothing and you leave with nothing. Mrs. Amina Koya was a pillar of strength to her husband and children and was always willing to help anyone who needed her help…this is a great loss to Fiji….her life is motivation for all of us because of the way she lived it-with nobility and humility.”

The FLP leader Chaudhry expressed his deepest condolences at the passing away of Mrs Koya: ‘She will always be remembered with honour and respect as the wife of the late Mr Siddiq Koya, former Leader of the Opposition and one of Fiji’s esteemed leaders who helped shape our country in its formative years. Mrs Koya will be remembered in her own right as a person of remarkable fortitude who stood firmly by her husband throughout the vicissitudes of his political career. I regret I am not able to personally pay my last respects to her as I am currently away in India. My sympathies and that of the Fiji Labour Party to her children Faiyaz, Faizal and Shehnaz, and to other members of the family.”

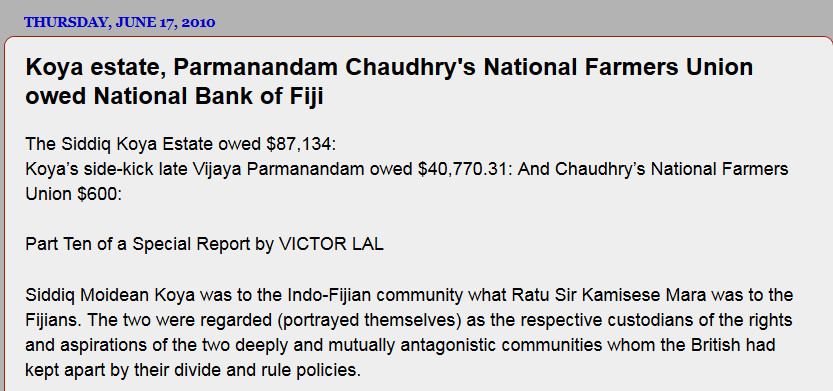

It is true that the dead do not tell tale but Mrs Koya’s death is yet to answer one intriguing question: who took out that loan of $87,174 from the collapsed National Bank of Fiji, a loan which never featured in her original trial and conviction in the High Court in Lautoka nor during her appeal before the Fiji Court of Appeal and in the Supreme Court. The three courts all heard of her financial woes but nothing about the debt to the NBF. Was it the late Siddiq Koya who took out that loan or was it Mrs Koya, perhaps, to finance the education of her two sons in London?

When was that loan taken out: before Koya’s death or after she had invited Fiji’s present Chief Justice Anthony Harold Cumberland Thomas Gates to take over the running of the law firm, Koya and Company. In the 1996 NBF Debtors List, the Estate of Koya is listed as one of the defaulting borrowers.

As Nazhat Shameem, who was charged with the uphill task of prosecuting the NBF loans scam once remarked, what was supposed to be an affirmative action program to advance soft loans to the disadvantaged indigenous population was in fact a slush fund for the privileged, many of whom were not even indigenous? How true; the Koya estate definitely falls in the last category.

The Koyas’ were not alone, for other non-Fijians also borrowed from collapsed NBF besides the elite as well as chiefly Fijians, resulting in a loss of $372million to the taxpayers.

Vijaya Parmanandam

Siddiq Koya’s side-kick, the lawyer, NFP parliamentarian and Deputy Speaker of Parliament, the late Vijaya Parmanandam, owed the NBF $40,770.31.

C/4 Editor’s Note: We will continue to reveal debtors names, which includes those of high chiefs, politicians, Indo-Fijians, business houses, including individual supporters of the present illegal junta in Fiji. If you or your family have paid back the NBF loans, please provide Victor Lal with evidence. He can be reached at [email protected]

In June 2009 Coupfourpoint Five also revealed that Faizal and Faiyaz Koya, the two sons of former NFP & Opposition leader, the late Siddiq Koya, were facing a $184,000 bankruptcy claim – which sources said could have led to Faizal Koya’s decision to accept appointment as a magistrate under the New Legal Order. According to the sources, it could not be established whether the $184,000 was trust funds kept by the law firm operated by the two brothers or by their late father.

See Koya bankruptcy papers

HYPERLINK "http://www.mediafire.com/?zyitj3nntyb" http://www.mediafire.com/?zyitj3nntyb

"Yet he does not leave the guilty unpunished; he punishes the children and their children for the sin of the fathers to the 3 and 4th generations" Exodus 34:7.