Fijileaks: Unlike previous overthrow of democratically elected governments by Rabuka and Bainimarama, this time around, the overthrow of the Coalition government will be constitutional - for the RFMF is legally mandated to carry it out in the 2013 Constitution of Fiji. That is if it is executed by the Commander Ro Jone Kalouniwai, and not by some rogue elements in the military. We are also tired of being reminded that the 2013 Constitution is ILLEGAL. If the detractors want to talk about illegality, we need to accept that the only constitution that was legal was the 1970 Constitution that Rabuka tore apart and had replaced it with a racially discriminatory and autocratic 1990 Constitution of Fiji. It was under this Constitution that he ruled Fiji until he lost the 1999 election.

*Fijileaks to Tikoduadua: COUPIST Bainimarama, your former PAYMASTER, like Rabuka before him, is once again appealing to the raw instincts of the RFMF foot soldiers who are protectors of the nation under Section 131 of the Constitution of Fiji, under which you are serving in Rabuka's Coalition government.

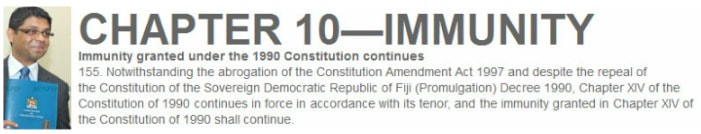

*It is time you called for the stripping of IMMUNITY that was inscribed into the 1990, 1997 and 2013 Constitutions, and let the Fiji High Court rule on its validity.

*It is shocking that the late NFP leader JAI RAM REDDY, arguably one of the best legal minds, had agreed to the IMMUNITY provision in the 1997 Constitution but then both Reddy and Rabuka were only interested in POLITICS and not whether the Immunity Clause was legal or illegal.

*In 2004, our Founding Editor-in-Chief had argued that the Immunity granted to Rabuka was illegal (see below). This was upheld by a group of human rights lawyers in London in 1999 when there were plans to arrest Rabuka based on the Chilean dictator General Pincohet precedent. And, only last year, another set of lawyers came to the same conclusion when we had planned to arrest the suspended Police Commissioner Sitiveni Qiliho for beating and torturing the late Brij Lal, and other opponents of the Bainimarama regime. Tikoduadua, you should never have agreed to become PS to Bainimarama, and later a FFP government minister.

TREASON IS TREASON, whether by Bainimarama or Rabuka

Our Founding Editor-in- Chief's Opinion in the Fiji Sun of 2004 on Rabuka's dubious Immunity:

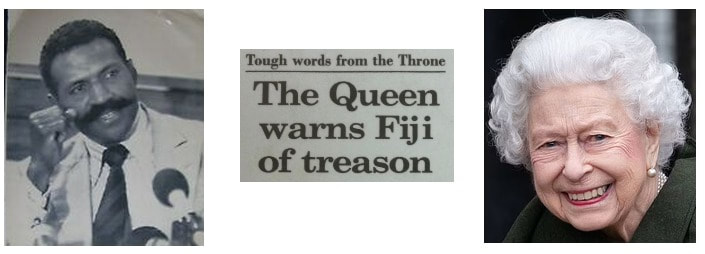

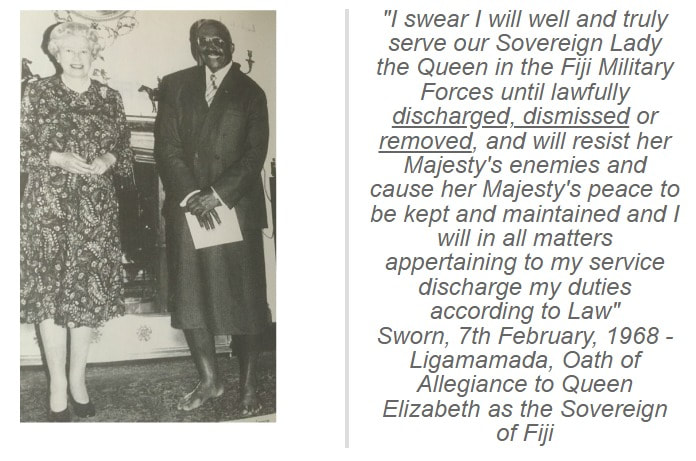

"The Queen’s representative, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, pardoned Rabuka before he declared Fiji a Republic but it was unconstitutional act

Her Majesty was saddened the coup-colonel severed 113-year old chiefly link with British Brown"

"As Professor Yash Ghai and Jill Cottrell (in a chapter to a book Sovereigns and Surrogates-Constitutional Heads of State in the Commonwealth, 1991) have pointed out, it seems that the G-G confused two powers: that to grant a pardon, and that to grant immunity from prosecution, the second of which he did not possess. The 1970 Fiji Constitution contemplated only the former, furthermore, even that power which the G-G possessed under the Constitution, was to be exercised only on the advice of the committee established for the purpose. In other words, Rabuka’s pardon, or immunity was, and still is, questionable in the eyes of the law. Moreover, the Queen had never consented to the pardoning. She had simply ceased to be the Head of State when Ratu Penaia resigned on 15 October, and Fiji’s membership of the Commonwealth had lapsed. On 14 May 1987, Rabuka therefore committed treason against Queen Elizabeth 11 of England and Fiji but escaped the death penalty."

2004: Victor Lal

2004: Victor Lal By VICTOR LAL

The Fiji Sun, 2004

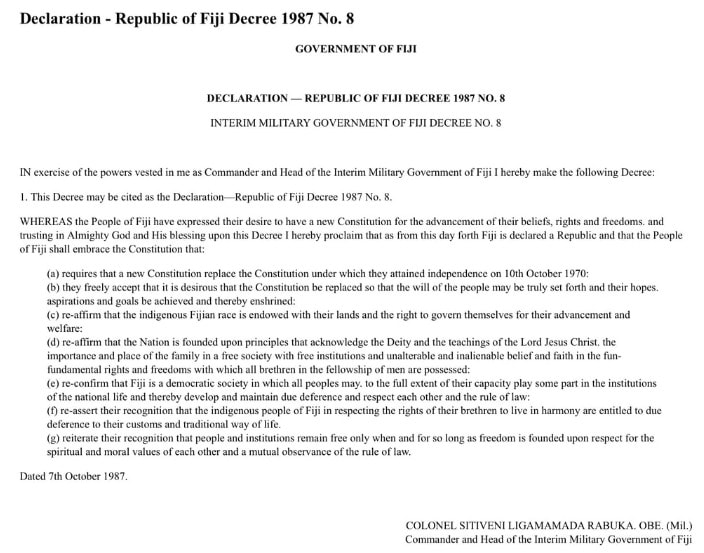

In a robust defence of his treasonable coups of 1987, Sitiveni Rabuka now claims that he did not have to ask for a pardon because he had already ousted Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth 11, and made Fiji a republic after the coups.

He was responding to questions raised by government senator, Reverend Tomasi Kanailagi, in the Senate on why the people who staged the coup in 2000 have not been pardoned, although the 1987 coup leader was allowed to walk free.

Responding, Rabuka said: ‘Kanailagi has no in-depth knowledge on what he is talking about because I didn't have to be pardoned by anyone ... the only one who could have pardoned me was the Queen, whom I ousted in that coup. I had effectively removed her.

Was Rabuka pardoned?

In order to answer the question we need to examine the events between 19 May 1987 when Rabuka and others were granted prerogative of mercy; 5 October 1987, when he declared Fiji a republic, and 15 October when Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau resigned as Governor-General. Rabuka had never ousted the Queen; she had ceased to be the head of state on 15 October. Moreover, throughout the 2000 Speight crisis, Rabuka had claimed that he could not be prosecuted because he had obtained immunity from prosecution for his 1987 actions. If that is so, then he was either ‘pardoned’ or granted ‘immunity’.

On 19 May 1987, the Governor-General (G-G), Ratu Penaia, who was also the tribal head of Rabuka’s Cakaudrove province, pardoned Rabuka for his exemplary behaviour after overthrowing the Bavadra government and on the pretext of helping to restore democracy. The G-G went even further, and on the 29 May, promoted Rabuka to full colonel and commander of the military, effective from the date of the coup, 14 May. Ratu Penaia also promoted other officers who had taken part in the coup as well. From the perspective of Fijian provincial and tribal politics, the effect was to strengthen the position of officers from Cakaudrove at the expense of those from Lau and Tailevu.

The Great Republican Debate

On 20 July the Great Council of Chiefs (GCC) met in Suva for a three-day meeting to discuss various alternatives to solve the deepening constitutional, economic, and racial crisis. It was widely anticipated that the extremist Taukei Movement had planned to ask Ratu Penaia to step down and then have the GCC declare Fiji a republic, with an exclusive Fijian government. The Taukei Movement spokesman, speaking at the first day of the meeting, urged the chiefs to revoke the 1874 Deed of Cession and declare Fiji a republic. He was not alone in promoting such a course. Nine of the 14 provinces had passed resolutions calling for an immediate declaration of Fiji as a republic, while the other five had agreed to support a republic only if the G-G’s initiative to bring about a political compromise failed.

The next day the meeting heard Rabuka calling for the formation of a ‘Christian democratic state’ and retention of ties with the Queen, rather than a republic. The GCC, on Wednesday, much to the surprise of many, rejected, for the time being, the idea of declaring a republic, but reserved the right to do so in the future. Rabuka called the decision ‘a consensus between the objectives of the Taukei Movement, the aim of my coup, and the wishes of the Great Council of Chiefs’.

On Friday 31 July, Rabuka was officially installed as commander of the army, ironically, at the Queen Elizabeth Barracks, where he told the 1,500 invited guests: ‘I am really here today as the representative of the great chiefs and the people of Fiji. I am doing this for you.’ More importantly, he was still serving under the Queen’s representative, the G-G, who was also the Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Fiji Military Forces.

Meanwhile, Ratu Mara, Ratu Penaia and Bavadra tried to reach a compromise deal for interim power-sharing in the so-called ‘Deuba Accord’. Rabuka’s response was lukewarm but the Taukei Movement was violently opposed to it. It described the proposed power-sharing as ‘degrading and a sell-out’. Sakiasi Butadroka, the leader of the Fijian Nationalist Party, called for an immediate declaration of a republic. But Rabuka, with the help of the Taukei extremists, struck once again, on Friday 22 September, carrying out a second coup. He announced over Radio Fiji that he had assumed executive authority over the G-G. He detained Bavadra, who was heading west, and also placed the G-G under armed guard at Government House.

However, Ratu Penaia maintained he was still the legal authority and refused to endorse the second coup. He also refused to co-operate when Rabuka and a group of his military officers offered him the tabua (whale’s tooth) for ‘slighting’ their chief. One of Her Majesty’s English magistrates, John Small, was detained and also assaulted. Despite the bullying tactics, the Chief Justice Sir Timoci Tuivaqa and the judges of the Supreme Court refused to recognize Rabuka’s authority. Sir Timoci and the other judges still saw Ratu Penaia as Queen’s representative and repository of authority in Fiji. Rabuka even threatened to dismiss the G-G if it was necessary for ‘legitimising my assumption of executive authority’. Rabuka also disclosed that the ‘Governor-General did not accept’ his offer to become President. ‘It will take lions to move me out of here’, Ratu Penaia said later.

A frustrated Rabuka, therefore, announced that he had assumed full authority, and also indicated that he would declare a republic shortly and offer the presidency to Ratu Mara, which angered the great Lauan chief. The Chief Justice continued to be a thorn in Rabuka’s side. He stated that Rabuka’s proclamation had no legal standing until the G-G was physically removed from office. The worst was to follow. The Queen personally sent a message accusing Rabuka of disloyalty which was broadcast once over the radio in the Fijian language before being suppressed by the military:

She told the nation: ‘For her part Her Majesty continues to regard the Governor-General as her presentative and the sole authority in Fiji. Anyone who seeks to remove the Governor-General from office would in effect be repudiating his allegiance and loyalty to the Queen. Her Majesty hopes that even now the process of restoring Fiji to constitutional normality might be resumed Many Fijians hold firm their allegiance to the Crown and to the Governor-General as the Queen’s personal representative. The Queen would be deeply saddened if these bonds of mutual loyalty and affection which have long so held the Fijian people and the British monarchy together were to be restored.’

Even Siddiq Koya, now a spent political force, and who in 1970 had called for a republic with a Fijian head of state, tried to dissuade Rabuka from declaring a republic.

Briefly, after a long protracted struggle, Rabuka and Ratu Penaia came to a compromise allowing the G-G to act ‘in his own deliberate judgement’. Ratu Penaia had two options: he could resign and clear the way or he could ask the Queen to accept the changes to the constitution approved by him. That night, the G-G contacted the Queen and asked her to consider a constitution with sweeping changes that entrenched native Fijian paramountcy at the expense of the Indo-Fijian population. She refused.

On 9 October, Ratu Mara flew to London to have an audience with the Queen but she politely declined to see him. Instead, she flew to Vancouver to attend the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting. However, on 15 October, Ratu Penaia suddenly resigned. He wrote to her: ‘My endeavours to preserve constitutional government in Fiji have proved in vain, and I can see no alternative way forward.’ The Queen, in regretfully accepting the resignation, expressed her gratitude for his loyal services and admiration for his courageous efforts to prevent Fiji from becoming a republic, and added that she was sad ‘to think that the ending of Fijian allegiance to the Crown should have been brought about without the people of Fiji being given an opportunity to express their opinion on the proposal.’ On 5 December Ratu Penaia became the new President of Fiji. Rabuka was promoted Brigadier of the Royal Fiji Military Forces.

Pardon and Prerogative of Mercy

It is quite clear from the sequence of events that at no time had Rabuka ousted the Queen, nor had the Governor-General, until 15 October, ceased to be her constitutional representative in Fiji. Rabuka was however pardoned on 19 May 1987, when Ratu Penaia purported to grant immunity to Rabuka in respect of his treasonable actions in overthrowing the lawfully constituted government, by virtue of the prerogative of mercy. The prerogative of mercy is a special power vested in the Head of State, which enables him or her to pardon or reduce the sentence of a convicted person.

Historically, this power has been exercised only in the most exceptional circumstances, such as where a miscarriage of justice has resulted in the conviction of a person who is innocent, or where a prisoner becomes terminally ill, so that it would be overly harsh to require him to serve out his sentence.

But as Professor Yash Ghai and Jill Cottrell (in a chapter to a book Sovereigns and Surrogates-Constitutional Heads of State in the Commonwealth, 1991) have pointed out, it seems that the G-G confused two powers: that to grant a pardon, and that to grant immunity from prosecution, the second of which he did not possess. The 1970 Fiji Constitution contemplated only the former, furthermore, even that power which the G-G possessed under the Constitution, was to be exercised only on the advice of the committee established for the purpose.

In other words, Rabuka’s pardon, or immunity was, and still is, questionable in the eyes of the law.

Moreover, the Queen had never consented to the pardoning.

She had simply ceased to be the Head of State when Ratu Penaia resigned on 15 October, and Fiji’s membership of the Commonwealth had lapsed.

On 14 May 1987, Rabuka therefore committed treason against Queen Elizabeth 11 of England and Fiji but escaped the death penalty.

On 19 May he was resigned to face the gallows, as he boasted: ‘The penalty for treason in all Commonwealth countries is death, and if this is to be my destiny I will accept it.’

But on the same day he managed to extract a questionable pardon, or immunity, from Ratu Penaia who, on 23 May, confirmed that he had granted Rabuka an amnesty.

It therefore follows that Reverend Kanailagi is correct in his assertion in the Senate.

But the pardon was, and remains, illegal because the Queen was still head of state until 15 October 1987, and the G-G had not followed the right procedure as required of him under the Constitution.

She had never authorized Ratu Penaia to perform the unconstitutional act of pardon.

Ratu Penaia himself had refused to accept the illegal takeover at the time of the pardoning

.

He was still, legally, ‘The Queen’s Man’ on the ground in Fiji. And the Queen, the Head of State.

In June 1987 we were even celebrating Her Majesty’s birthday, while Fiji was burning with racial and political strife.

In passing, amnesty was further entrenched in the 1990 racist Constitution and again in the 1997 Constitution, and impunity was not restricted to Rabuka and his close accomplices like Senator Apisai Tora, who played a major role in the destabilization of the Bavadra government.

Even that amnesty and impunity is now in doubt.

For Tora has tabled a motion in the Senate to establish a Commission of Inquiry into the validity of the Constitution.

Is Tora, inadvertently, also prizing open the legal net to bring Rabuka, and many others sitting in the Senate with Tora from the 1987 coups and its aftermath, to justice for treason?

In the old days, there were the hanging, drawing and quartering (including disembowelment while the offender was still alive) of men convicted of high treason in England.

The Fiji Sun, 2004

In a robust defence of his treasonable coups of 1987, Sitiveni Rabuka now claims that he did not have to ask for a pardon because he had already ousted Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth 11, and made Fiji a republic after the coups.

He was responding to questions raised by government senator, Reverend Tomasi Kanailagi, in the Senate on why the people who staged the coup in 2000 have not been pardoned, although the 1987 coup leader was allowed to walk free.

Responding, Rabuka said: ‘Kanailagi has no in-depth knowledge on what he is talking about because I didn't have to be pardoned by anyone ... the only one who could have pardoned me was the Queen, whom I ousted in that coup. I had effectively removed her.

Was Rabuka pardoned?

In order to answer the question we need to examine the events between 19 May 1987 when Rabuka and others were granted prerogative of mercy; 5 October 1987, when he declared Fiji a republic, and 15 October when Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau resigned as Governor-General. Rabuka had never ousted the Queen; she had ceased to be the head of state on 15 October. Moreover, throughout the 2000 Speight crisis, Rabuka had claimed that he could not be prosecuted because he had obtained immunity from prosecution for his 1987 actions. If that is so, then he was either ‘pardoned’ or granted ‘immunity’.

On 19 May 1987, the Governor-General (G-G), Ratu Penaia, who was also the tribal head of Rabuka’s Cakaudrove province, pardoned Rabuka for his exemplary behaviour after overthrowing the Bavadra government and on the pretext of helping to restore democracy. The G-G went even further, and on the 29 May, promoted Rabuka to full colonel and commander of the military, effective from the date of the coup, 14 May. Ratu Penaia also promoted other officers who had taken part in the coup as well. From the perspective of Fijian provincial and tribal politics, the effect was to strengthen the position of officers from Cakaudrove at the expense of those from Lau and Tailevu.

The Great Republican Debate

On 20 July the Great Council of Chiefs (GCC) met in Suva for a three-day meeting to discuss various alternatives to solve the deepening constitutional, economic, and racial crisis. It was widely anticipated that the extremist Taukei Movement had planned to ask Ratu Penaia to step down and then have the GCC declare Fiji a republic, with an exclusive Fijian government. The Taukei Movement spokesman, speaking at the first day of the meeting, urged the chiefs to revoke the 1874 Deed of Cession and declare Fiji a republic. He was not alone in promoting such a course. Nine of the 14 provinces had passed resolutions calling for an immediate declaration of Fiji as a republic, while the other five had agreed to support a republic only if the G-G’s initiative to bring about a political compromise failed.

The next day the meeting heard Rabuka calling for the formation of a ‘Christian democratic state’ and retention of ties with the Queen, rather than a republic. The GCC, on Wednesday, much to the surprise of many, rejected, for the time being, the idea of declaring a republic, but reserved the right to do so in the future. Rabuka called the decision ‘a consensus between the objectives of the Taukei Movement, the aim of my coup, and the wishes of the Great Council of Chiefs’.

On Friday 31 July, Rabuka was officially installed as commander of the army, ironically, at the Queen Elizabeth Barracks, where he told the 1,500 invited guests: ‘I am really here today as the representative of the great chiefs and the people of Fiji. I am doing this for you.’ More importantly, he was still serving under the Queen’s representative, the G-G, who was also the Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Fiji Military Forces.

Meanwhile, Ratu Mara, Ratu Penaia and Bavadra tried to reach a compromise deal for interim power-sharing in the so-called ‘Deuba Accord’. Rabuka’s response was lukewarm but the Taukei Movement was violently opposed to it. It described the proposed power-sharing as ‘degrading and a sell-out’. Sakiasi Butadroka, the leader of the Fijian Nationalist Party, called for an immediate declaration of a republic. But Rabuka, with the help of the Taukei extremists, struck once again, on Friday 22 September, carrying out a second coup. He announced over Radio Fiji that he had assumed executive authority over the G-G. He detained Bavadra, who was heading west, and also placed the G-G under armed guard at Government House.

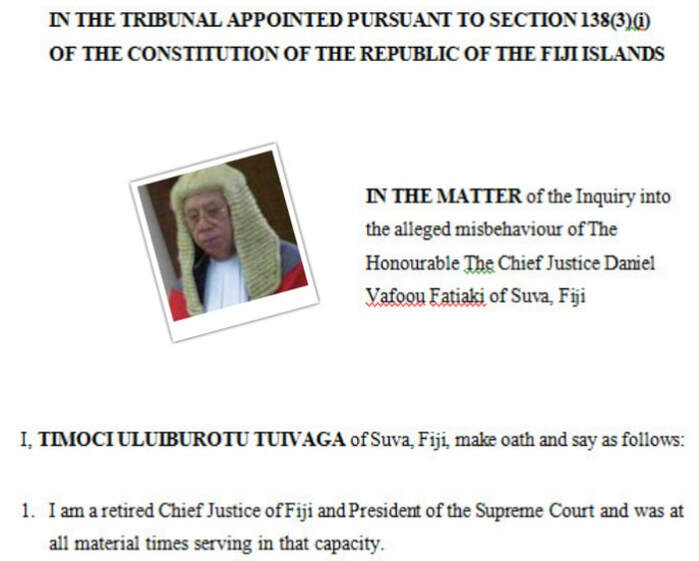

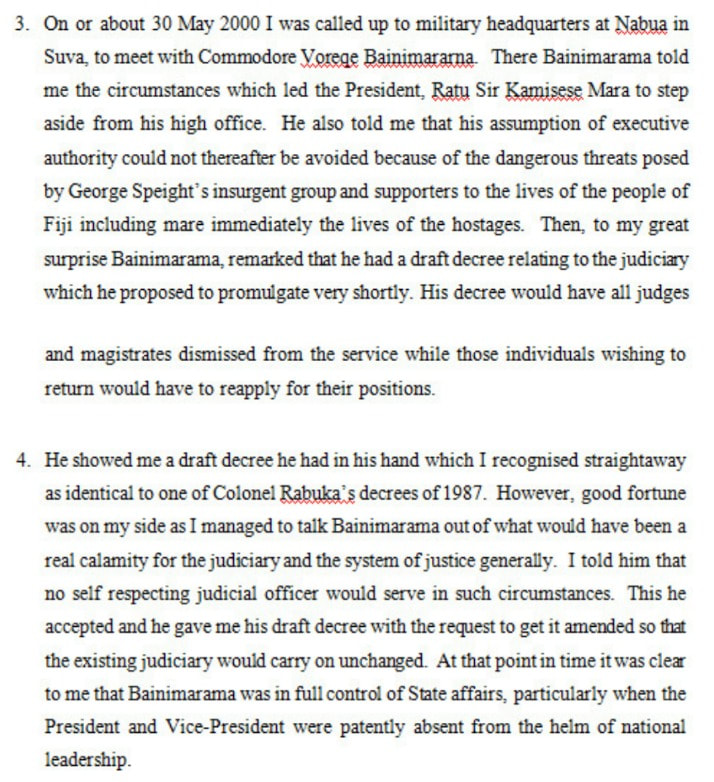

However, Ratu Penaia maintained he was still the legal authority and refused to endorse the second coup. He also refused to co-operate when Rabuka and a group of his military officers offered him the tabua (whale’s tooth) for ‘slighting’ their chief. One of Her Majesty’s English magistrates, John Small, was detained and also assaulted. Despite the bullying tactics, the Chief Justice Sir Timoci Tuivaqa and the judges of the Supreme Court refused to recognize Rabuka’s authority. Sir Timoci and the other judges still saw Ratu Penaia as Queen’s representative and repository of authority in Fiji. Rabuka even threatened to dismiss the G-G if it was necessary for ‘legitimising my assumption of executive authority’. Rabuka also disclosed that the ‘Governor-General did not accept’ his offer to become President. ‘It will take lions to move me out of here’, Ratu Penaia said later.

A frustrated Rabuka, therefore, announced that he had assumed full authority, and also indicated that he would declare a republic shortly and offer the presidency to Ratu Mara, which angered the great Lauan chief. The Chief Justice continued to be a thorn in Rabuka’s side. He stated that Rabuka’s proclamation had no legal standing until the G-G was physically removed from office. The worst was to follow. The Queen personally sent a message accusing Rabuka of disloyalty which was broadcast once over the radio in the Fijian language before being suppressed by the military:

She told the nation: ‘For her part Her Majesty continues to regard the Governor-General as her presentative and the sole authority in Fiji. Anyone who seeks to remove the Governor-General from office would in effect be repudiating his allegiance and loyalty to the Queen. Her Majesty hopes that even now the process of restoring Fiji to constitutional normality might be resumed Many Fijians hold firm their allegiance to the Crown and to the Governor-General as the Queen’s personal representative. The Queen would be deeply saddened if these bonds of mutual loyalty and affection which have long so held the Fijian people and the British monarchy together were to be restored.’

Even Siddiq Koya, now a spent political force, and who in 1970 had called for a republic with a Fijian head of state, tried to dissuade Rabuka from declaring a republic.

Briefly, after a long protracted struggle, Rabuka and Ratu Penaia came to a compromise allowing the G-G to act ‘in his own deliberate judgement’. Ratu Penaia had two options: he could resign and clear the way or he could ask the Queen to accept the changes to the constitution approved by him. That night, the G-G contacted the Queen and asked her to consider a constitution with sweeping changes that entrenched native Fijian paramountcy at the expense of the Indo-Fijian population. She refused.

On 9 October, Ratu Mara flew to London to have an audience with the Queen but she politely declined to see him. Instead, she flew to Vancouver to attend the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting. However, on 15 October, Ratu Penaia suddenly resigned. He wrote to her: ‘My endeavours to preserve constitutional government in Fiji have proved in vain, and I can see no alternative way forward.’ The Queen, in regretfully accepting the resignation, expressed her gratitude for his loyal services and admiration for his courageous efforts to prevent Fiji from becoming a republic, and added that she was sad ‘to think that the ending of Fijian allegiance to the Crown should have been brought about without the people of Fiji being given an opportunity to express their opinion on the proposal.’ On 5 December Ratu Penaia became the new President of Fiji. Rabuka was promoted Brigadier of the Royal Fiji Military Forces.

Pardon and Prerogative of Mercy

It is quite clear from the sequence of events that at no time had Rabuka ousted the Queen, nor had the Governor-General, until 15 October, ceased to be her constitutional representative in Fiji. Rabuka was however pardoned on 19 May 1987, when Ratu Penaia purported to grant immunity to Rabuka in respect of his treasonable actions in overthrowing the lawfully constituted government, by virtue of the prerogative of mercy. The prerogative of mercy is a special power vested in the Head of State, which enables him or her to pardon or reduce the sentence of a convicted person.

Historically, this power has been exercised only in the most exceptional circumstances, such as where a miscarriage of justice has resulted in the conviction of a person who is innocent, or where a prisoner becomes terminally ill, so that it would be overly harsh to require him to serve out his sentence.

But as Professor Yash Ghai and Jill Cottrell (in a chapter to a book Sovereigns and Surrogates-Constitutional Heads of State in the Commonwealth, 1991) have pointed out, it seems that the G-G confused two powers: that to grant a pardon, and that to grant immunity from prosecution, the second of which he did not possess. The 1970 Fiji Constitution contemplated only the former, furthermore, even that power which the G-G possessed under the Constitution, was to be exercised only on the advice of the committee established for the purpose.

In other words, Rabuka’s pardon, or immunity was, and still is, questionable in the eyes of the law.

Moreover, the Queen had never consented to the pardoning.

She had simply ceased to be the Head of State when Ratu Penaia resigned on 15 October, and Fiji’s membership of the Commonwealth had lapsed.

On 14 May 1987, Rabuka therefore committed treason against Queen Elizabeth 11 of England and Fiji but escaped the death penalty.

On 19 May he was resigned to face the gallows, as he boasted: ‘The penalty for treason in all Commonwealth countries is death, and if this is to be my destiny I will accept it.’

But on the same day he managed to extract a questionable pardon, or immunity, from Ratu Penaia who, on 23 May, confirmed that he had granted Rabuka an amnesty.

It therefore follows that Reverend Kanailagi is correct in his assertion in the Senate.

But the pardon was, and remains, illegal because the Queen was still head of state until 15 October 1987, and the G-G had not followed the right procedure as required of him under the Constitution.

She had never authorized Ratu Penaia to perform the unconstitutional act of pardon.

Ratu Penaia himself had refused to accept the illegal takeover at the time of the pardoning

.

He was still, legally, ‘The Queen’s Man’ on the ground in Fiji. And the Queen, the Head of State.

In June 1987 we were even celebrating Her Majesty’s birthday, while Fiji was burning with racial and political strife.

In passing, amnesty was further entrenched in the 1990 racist Constitution and again in the 1997 Constitution, and impunity was not restricted to Rabuka and his close accomplices like Senator Apisai Tora, who played a major role in the destabilization of the Bavadra government.

Even that amnesty and impunity is now in doubt.

For Tora has tabled a motion in the Senate to establish a Commission of Inquiry into the validity of the Constitution.

Is Tora, inadvertently, also prizing open the legal net to bring Rabuka, and many others sitting in the Senate with Tora from the 1987 coups and its aftermath, to justice for treason?

In the old days, there were the hanging, drawing and quartering (including disembowelment while the offender was still alive) of men convicted of high treason in England.