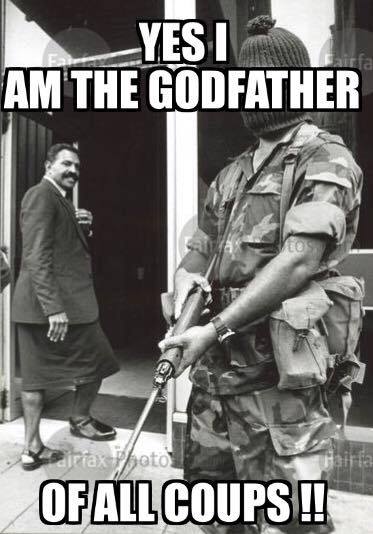

Fijileaks: We are not cheerleaders of either of the two coupists but Bainimarama was absolutely right to dismiss SODELPA's call for a debate between himself and Rabuka. After all, Rabuka lost the 1999 election whereas Bainimarama was declared winner of the 2014 general election. Politically, Rabuka ruled Fiji between 1987 and 1999 under the RACIST 1990 Constitution. He, therefore, lacks experience to debate politics!

"The SVT was politically opportunistic and in order to make up the expected loss of seats to rival Fijian parties, it had gone into coalition with the NFP, believing that the NFP was the party of the Indo-Fijians. The NFP, on the other hand, had taken for granted that the SVT represented the Fijian voters. The confidence and cockiness of the two coalition partners can be seen from their announcement regarding political leadership. If the SVT-NFP Coalition had come to power, Rabuka was to become prime minister and Reddy was supposed to be his deputy prime minister (i.e. a Fijian Prime Minister and an Indo-Fijian Deputy Prime Minister). It is unfair and despicable for both the SVT and NFP leaders to accuse the Indo-Fijian community of electoral betrayal." - VICTOR LAL, Fiji's Daily Post, 2001

From Fiji's Daily Post archive, 2001,

By VICTOR LAL:

The 1997 Constitution: Beauty and the Beast and 1999 General Election

"The former army commander [Rabuka] had taken his troops into the electoral battle without any major preparation and was comprehensively beaten at the polls. As they say in military language, his electoral troops were called upon to take on the political enemy on empty stomachs."

By VICTOR LAL

By VICTOR LAL Commenting on the election results, Mahendra Chaudhry claimed that the FLP's victory was the result of the people's 'frustration' at problems of unemployment, poverty, crime, failure of government services and income disparity between the rich and the poor. An editorial in The Fiji Times observed that the FLP won because of its multicultural image and 'its image as a caring, humane party that stays close to the grassroots people'.

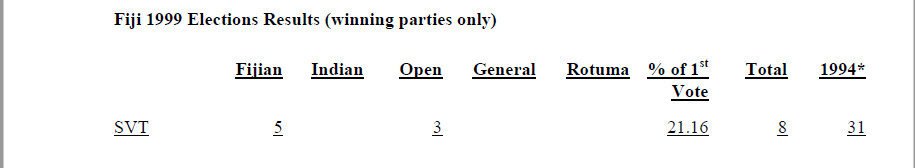

The SVT, on the other hand, as the result of competition from rival indigenous Fijian parties also lost ground with five Ministers losing their seats. It won eight compared to 31 seats in 1994. In contrast to the Indo-Fijian seats, the contest for votes in the Fijian communal seats was more even. The other indigenous Fijian parties, FAP, PANU, VLV and the extremist NVTLP won at the expense of SVT, 11, four, three and one seats respectively. In a number of cases (and in one where an independent won) the new 'alternate vote' system contributed to the loss of SVT seats. There have been calls to return to the old system. The SVT also became a victim of 'disunity among chiefs who set up and supported new Fijian political parties'.

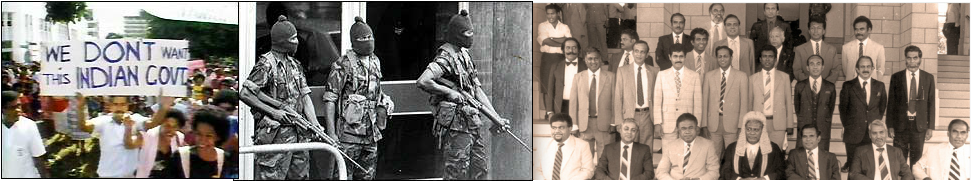

Many Fijians saw the election results as a repeat of 1987. This was the view of Apisai Tora, secretary-general of PANU and Bau Chief Adi Litia Cakobau of SVT, who also observed that the Fijian votes were split and many of the chiefs lost their seats because the people wanted a change. The Nationalists, in a meeting after the elections, made a 'blood pledge' to overthrow the Chaudhry government and constitution and to introduce a Fijianisation policy.

The Impact of Coalitions: Myth and Reality

A traditional conception of coalition politics might suggest that political parties compete independently during the election campaign to maximise their potential and engage in coalition bargaining only once the distribution of seats are known. But of course in reality electoral competition and coalition bargaining are not so neatly sequential. After all, one matter that voters are likely to be interested in during the campaign is the identity of the new government to be formed. Most parties want to appear relevant to the business of forming a government in order to attract floating voters. They thus have incentives to suggest that they are well positioned to join a winning coalition. In many countries parties do this either by forming electoral coalitions or at least by signalling with whom they will (and perhaps with whom they will not) try to form a government once the dust has settled and the explicit post-election bargaining begins.

As already noted, the SVT/NFP/UGP was the first to declare itself as a coalition. In March 1999 the FAP/PANU/FLP led by Adi Kuini, Tora, and Chaudhry, announced their coalition.

Much has been made of the fact that the SVT lost the election because it went into Coalition with the NFP. The same has been said of the defeat of the NFP. The truth is that the SVT lost because the Fijian voters (62 per cent) took their votes to the other Fijian parties. The SVT only got 38 per cent of the Fijian votes. As for the NFP, it is preposterous for the NFP and its politicians to argue that the Indo-Fijians bloc voted for the FLP because they had not forgiven Rabuka and the violence and brutality his two coups had unleashed on them. It might be partly true. However, the Indo-Fijian votes went to the FLP because for the first time the Indo-Fijian community came to its senses that it could not be taken for a ride by the NFP and its leaders like they had done with their lives since 1969. A new generation of Indo-Fijian voters had seen nothing but a slow and steady strangulation of their economic, educational, and political rights by supporting the NFP. The sins of their fathers continued to be visited on their sons as long as they remained under the false protection of the NFP.

It was the Peoples Coalition which should have been punished at the polls. For the spectre of Apisai Tora and his PANU in coalition with Chaudhry was a far greater evil in the minds of the Indo-Fijian voters than the moderate Reddy and the supposedly born-again Methodist lay preacher Rabuka. Tora evokes far greater fear in the Indo-Fijian community with his past history of racial violence and repeated calls for the expulsion of Indo-Fijians than Rabuka, who had come across before the elections as a committed multi-racialist.

The Indo-Fijians were acutely aware that Tora had played a leading role in ousting Chaudhry, Reddy, and Bavadra from power in 1987. As we have already demonstrated, the Indo-Fijian voters were more concerned with daily bread and butter issues than the achievements of Reddy and Rabuka giving them a new Constitution. Many Indo-Fijian voters were also acutely aware that the SVT and Rabuka had buckled under international pressure to make changes to the 1990 Constitution. There was no serious change of heart on the part of Rabuka or the SVT as recent events and constitutional developments have once again confirmed.

The SVT was politically opportunistic and in order to make up the expected loss of seats to rival Fijian parties, it had gone into coalition with the NFP, believing that the NFP was the party of the Indo-Fijians. The NFP, on the other hand, had taken for granted that the SVT represented the Fijian voters. The confidence and cockiness of the two coalition partners can be seen from their announcement regarding political leadership. If the SVT-NFP Coalition had come to power, Rabuka was to become prime minister and Reddy was supposed to be his deputy prime minister (i.e. a Fijian Prime Minister and an Indo-Fijian Deputy Prime Minister). It is unfair and despicable for both the SVT and NFP leaders to accuse the Indo-Fijian community of electoral betrayal. It is curious to read that the Indo-Fijians are described as ‘political traitors’ while the non-SVT Fijians are being chided for exercising their democratic rights by casting their votes for other Fijian political parties.

As we have already shown, the SVT and Rabuka came to power in the 1994 elections because of the bloc votes of the military, the Church, and rural Fijian voters who were beneficiaries of the skewed 1990 Constitution in favour of rural Fijian voters over the urban Fijian voters. The SVT must be also mentally devoid of historical memory.

It was not their arch rival, a former political saviour and current bogeyman-Mahendra Chaudhry-but their new-found coalition angel Jai Ram Reddy and the NFP which had thrown in their political support for Kamikamica against Rabuka in the 1992 leadership crisis. Maybe, the Fijian voters had a greater retentive memory of Reddy’s part in the leadership contest, which they presumably did, than the SVT and Rabuka. Maybe, they could not trust Reddy in a future government with Rabuka. The SVT must ask itself: Why did it make an electoral pact with the political ‘devils’ in the NFP who had no confidence in their leader Rabuka’s leadership of the nation?.

In passing, we would like to also point out that it is grossly insulting and unfair to blame the Indo-Fijian community for exercising their democratic right to cast their votes for the FLP. Why no call has been made to unite the Indo-Fijians through a new constitution similar to that now being made by the Interim Government, SVT, and the Great Council of Chiefs. Why should and must the Fijians be a united race and the Indo-Fijians a divided race? As we will show one of these days, the Indo-Fijians have always been prepared to embrace multi-racialism, and it was for this reason that the Alliance Party was able to stay in power for too long.

Meanwhile, the 1997 Constitution was taken for granted by the SVT/NFP Coalition as a right of passage to power. Rabuka’s biographer, John Sharpham recounts Rabuka’s optimism as his grip on the country was sliding by the hour: ‘Monday revealed how difficult it was going to be, for late on Monday it was clear that the election was turning into a rout. Reddy and the NFP were being trounced everywhere and by huge margins. Even key NFP candidates who had been tipped to enter Rabuka’s Cabinet, like Wadan Narsey, the young academic turned politician, were comprehensively beaten. Reddy, who had chosen, like Rabuka to run in an open seat, to prove the principle of multiracial support, was beaten handily. Tired, dispirited and unwell, he was ready to retire from politics forever and return to his successful law practice. The NFP lost all nineteen seats of the Indian communal seats to Labour. The eleven Open seats that Rabuka had given the NFP as part of the Coalition arrangement were also in jeopardy. The NFP had, effectively been destroyed by Chaudhry and the Labour Party, and by their commitment to the multiparty, multiracial Constitution. It was not just the NFP that was being mauled. The SVT was also in deep trouble. Apart from a few seats in the north and Jim Ah Koy’s win in Kadavu, there was little to show for all the hard work. Preferential voting, the AV system, was working against the SVT. Unless a candidate won on the first count, gaining 50 per cent plus one vote, the seat count then went to preferences. All their opposition parties had agreed to place their preferences against the SVT. It was virtually impossible for the SVT candidate to win if the vote went to preferences. The division among the Fijians, their fragmentation into eleven different parties, was now counting against the party that had been created to unite them.’

Rabuka flew into Suva and called a two-hour meeting with Ratu Inoke Kubuabola and Jim Ah Koy. To quote Sharpham: ‘The mood in the Prime Minister’s office area was a gloomy one. Workmen moved up and down the hall outside making drastic changes to the rooms on the fourth floor. These refurbishments had been planned for the incoming government, expected to be led by Rabuka. A different Cabinet and a new prime Minister would be using these improved facilities. Amidst the gloom of his staff and the noise of the builders Rabuka was upbeat. He talked over the options for the future with Ah Koy and Kubuabola. From time to time, his Cabinet secretary joined them to offer advice about the timing of resigning and conceding. At this stage Rabuka still believed the SVT and the UGP might win twenty seats and so be offered a Cabinet seat. Should they accept and support the multi-party approach? The longer they talked, the clearer the news became that the Labour Party would win a strong mandate. Ah Koy was, from the beginning, all for going into opposition. Eventually the others agreed, but Rabuka wanted to wait another day, just to see the results. He held out no hopes for any change, but the final vote count needed to be announced formally to make the situation absolutely clear.’

The election results recorded a resounding victory for the Peoples Coalition. Rabuka insisted that the Constitution had been the correct issue on which to fight the election. His SVT had managed to win only eight seats in a new Parliament. The man responsible for this humiliation was no other than Mahendra Pal Chaudhry who had just won his own seat in Ba West. The westerly wind of change was blowing towards the south - the capital Suva- for the Peoples Coalition to occupy the newly furbished office of the Prime Minister. Chaudhry was a strong contender for the most coveted post. ‘I have never lost an election’, Rabuka told his supporters, ‘I am an army man and I have learned you must always be prepared for defeat’. The truth of the matter was Chaudhry and the Fiji Labour Party had regained what Rabuka had stolen from them at the point of a gun in 1987. His nemesis was a man called Chaudhry.

As Sharpham notes, ‘The final results of the election showed the devastation that the hurricane called Chaudhry, had caused to Rabuka’s Coalition. The SVT held just eight seats, enough to be invited to hold a Cabinet seat, but which Rabuka had rejected. The NFP had not won a single seat, while the UGP had done its part and won two. Chaudhry and the Fiji Labour Party had had a magnificent victory winning a mandate in their own right with 37 seats. The FAP had won ten seats, two more than the SVT, giving them a right to say they spoke for the Fijians, and PANU had own four. The Peoples Coalition had an overwhelming hold on the House of Representatives with 51 of the 71 seats. Rabuka, for his part, believed Chaudhry and his supporters had acted against the spirit of the new Constitution. He was dismayed that race was still so dominant a political factor, especially among the Indo-Fijians’.

As we have already stated, Rabuka’s statement was a perversity of truth and reality. The Indo-Fijians could no longer be taken for a ride by the NFP, especially the new breed of Indo-Fijian voters. The enemy, in fact, was from within the Fijian community. They were no longer going to be fooled by the SVT, especially over 60 per cent of the Fijian voters. They had voted en bloc for other Fijian parties. Race had been subsumed in the politics of coalition. And only one of the two Coalitions was bound to emerge as a political winner.

In this instance, it was the Chaudhry led Peoples Coalition. The former army commander had taken his troops into the electoral battle without any major preparation and was comprehensively beaten at the polls. As they say in military language, his electoral troops were called upon to take on the political enemy on empty stomachs.

In the next column, we will show how the Fijians inside the Coalition shamelessly tried to take advantage of the provisions for power sharing in the 1997 Constitution as they raced for the Prime Minister, fatally damaging Mahendra Chaudhry in the process. The Fijian nationalists and the SVT had no opportunity to directly invoke the ‘Race Card’ in the appointment of a new Prime Minister because they were not a part of the winning Coalition. Adi Kuini Speed and Apisai Tora however sanctioned the race card in the eyes of grassroots Fijians throughout Fiji by trying to put forward a Prime Minister of Fijian origin.

Chaudhry’s political world was thus bound to fall apart, and only Time was the silent spectator to tell when, how, and by whom in the murky world of Fijian tribal politics.