Opposition Leader Ro Kepa Teimumu's EASTER MESSAGE to Fiji

This Sunday, I will join thousands more and millions across the globe, in celebrating the resurrection of Christ and the salvation he offered mankind.

Holy Week and Easter are times for reflection and renewal. We fondly remember the grace of an awesome God, who loved us so dearly that He would give us his only Son, so that we might live through Him.

We recall all that Jesus endured for us regardless of religion, gender, age or race; the scorn of the crowds, the agony of the cross, all so that we might be forgiven of our sins and granted everlasting life.

As Christians we recommit ourselves to following His example, to love and serve one another, with a special emphasis on serving the less fortunate amongst us. This responsibility is not only to each other, but it is a responsibility to GOD. A contract that accepts all human beings and embraces humanity without hate or an agenda to self-serve the few at the expense of all else.

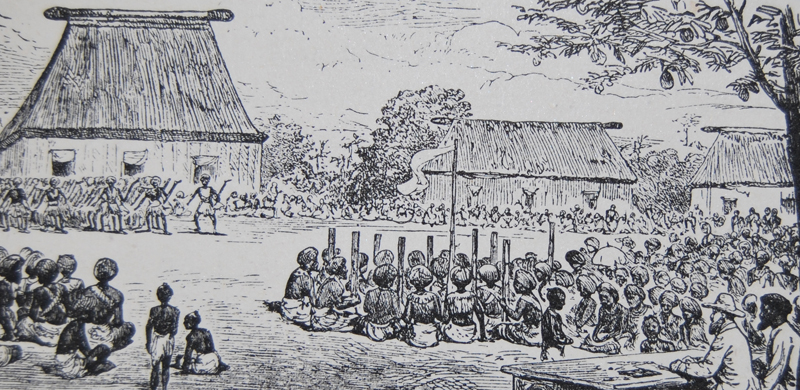

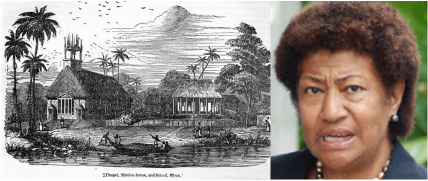

This week, we must also pay homage to the silent heroes who built Fiji. Those that came before the Indentured Laborers and the British. Those whose only passport was a Bible and a desire to share the Gospel with our ancestors. In the past, they were fondly remembered for bringing about civilization in Fiji and immortalised in our democracy’s founding documents.

Although there is a concerted effort to remove this history, I join the thousands who refuse to deny them the sanctified honor they deserve for placing their lives and that of their families on the line to transform our part of the world from the cannibal isles to the 300 islands under the sun we call Fiji. The Gospel is not irreverent to our times, and the church, while in pursuit of justice and freedom for all, can be an effective advocate for the re-democratization of Fiji

On this Easter weekend I ask that you join me in offering prayers for the poor and less fortunate citizens of Fiji, the people of Vanuatu and other Pacific communities devastated by the recent Cyclone Pam and the people of West Papua who are currently risking their lives for liberty and Justice, and the families of the recent Germanwings Flight 9525 crash. I also ask that you join me in prayer for the family and friends of the late Navneeta Devi."

Ro Teimumu Vuikaba Kepa

Leader of Oppositio

Opposition Leader Ro Teimumu Kepa confirms that Suva Lawyer Richard Naidu is her nominee for the Constitutional Offices Commission

Naidu

Naidu Ro Teimumu said she was delighted that Mr. Naidu had accepted her invitation to serve on the commission in accordance with the provisions of Sec 132 of the Constitution. She looked forward to working with Mr Naidu as Opposition nominee on the Commission.

Ro Teimumu said she had submitted Mr. Naidu’s name to the Solicitor General in January and was awaiting confirmation of his appointment by the President. The Opposition Leader said she has had to follow up with the Solicitor General for a response. She called on Government to quickly confirm its nominees so that the Commission can start work.

Mr. Naidu is one of Fiji’s most respected legal practitioners and is well known here and abroad as a fearless advocate for justice and the rule of law. He has himself been a victim of abuse at the hands of those who overthrew a legal government.

Ro Teimumu said during this time of transition from dictatorship to democracy, it was crucial for key positions such as those on the Constitutional Offices Commission to be occupied by citizens who are patriotic defenders of democracy. This would help ensure that the Government of the day is held to account for its decisions on the high public appointments that the Commission is mandated to make.

THE METHODIST MISSION AND FIJI'S INDIANS: 1879 - 1920

By Andrew Thornley, 1973

"Possibilities of the gravest danger lie in the fact that many hundreds of heathen men, differing in colour, in capabilities, in taste, in language, in aspirations, in beliefs, are flowing constantly into Fiji and are being brought into daily relationship with an aboriginal race, which has itself only recently stepped out of a cruel and barbarous heathenism." -

The Reverend H. Worrall, Rewa Circuit Report, 1894

'In India, thousands of low-caste people will listen to the missionary's message, because of the social emancipation it involves; but in Fiji, the Bhangi (scavenger) and the Brahmin eat together, and the Bhangi may have a high-caste woman for his wife. This means that the low-caste Indian in Fiji will not consider the claims of Christianity on account of the freedom from social disabilities it may offer, as he would if in his native land' -

A Visitor to Fiji, 1913

'The Fijian was a simple-minded man with a child's intellect .... There was strong moral resistance to the message but no mental opposition . . . . But the Christian Church in these Islands has an entirely different class to deal with in the Indian .... He is acknowledged to be one of the most subtle and acute thinkers the world has known .... Thus in addition to a moral resistance, we have to be prepared to face a mental one of the strongest and most unyielding sort.' Reverend Burton

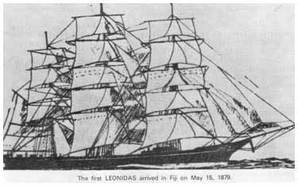

Leonidas carrying 463 indentured Indian labourers to Fiji

Leonidas carrying 463 indentured Indian labourers to Fiji But in 1879 the missionary vision of a 'Kingdom of God on Earth' received a severe setback with the arrival in Fiji of the emigrant ship, Leonidas, carrying 463 indentured Indian labourers. It was to be the first of many such ships. Sir Arthur Gordon, Fiji's first Governor, was opposed to the employment of indigenous labour for the expanding sugar, copra and cotton industries. Wishing to preserve the Fijian social structure from the less welcome effects of westernization, he introduced a scheme of foreign labour which had already proved successful in British colonies such as Mauritius and British Guiana. In the space of forty years, over 60,000 Indians emigrated from their home country to work as indentured labourers and (in the majority of cases) subsequently to settle in Fiji.

The Methodist missionaries viewed this influx of predominantly non-Christian Indians with dismay and even alarm. The efforts of five decades appeared to be threatened. One of the missionaries wrote: 'Possibilities of the gravest danger lie in the fact that many hundreds of heathen men, differing in colour, in capabilities, in taste, in language, in aspirations, in beliefs, are flowing constantly into Fiji and are being brought into daily relationship with an aboriginal race, which has itself only recently stepped out of a cruel and barbarous heathenism.'

Moreover, as the Fiji Methodist District Synod claimed in 1891, the heathen Indians were having a baneful influence on the natives. The commencement of evangelization among the Indians was therefore a matter of urgency, not only for their salvation but also for the preservation of the Fijian work. Missionaries were adamant about the extreme peril to which their native converts were being exposed by coming into daily contact with the 'superstition, immorality and vice of a shrewd, vigorous and ingenious foreign population'. There were reports of declining numbers and of low moral and spiritual tone among the Fijians, all attributable to the influx of outsiders.

Exactly how much and in what way the Indians influenced the Fijian church and society is impossible to estimate. Though invariably forecasting harm the missionaries spoke in general and conjectural terms. For instance the Reverend H. Worrall, who as Superintendent of the Rewa area from 1891 to 1896 was closely linked with the early Indian work, referred to vices and diseases which the Indian had brought to Fiji and asserted that they were affecting the religious, social and even physical life of the Fijian: 'The vast majority of Fiji's foreign population come into the country without their womenfolk. There are between four and five thousand less female than male Fijians! Let any man who knows anything of the native races couple these last two facts together and he will find that in them lies a dreadful significance.'

Of further concern to the Mission was the fact that the Fijian population was declining while the Indian growth-rate gave little hint of receding. Evangelization of the new immigrants was therefore imperative in order to save the native church from 'one of the most serious perils by which it has ever been menaced'.

Suva and the Rewa river area served as the centres of mission outreach in its initial stages. But the early years were a mixture of enthusiastic effort and half-hearted support. From 1892 to 1894 an Indian catechist, John Williams, ministered to both the 'free' Indians in Suva and the indentured Indians working in the proximity of present-day Nausori. He was considered a most capable and energetic preacher, achieving a greater degree of success among the Indians of Suva than within the larger indentured population. As with later mission workers, Williams had great difficulty in gaining access to the labour 'lines'. Employers of indentured Indians were, it seems, loath to allow the preaching of the Gospel; they informed at least one missionary that 'the field mules were a more suitable object for Christian effort' and claimed that 'if coolies were educated they would be spoilt as labour'.

Field coolie mules and whips

Field coolie mules and whips By the time of his departure he had established a network of preaching places associated with the Indian work and had the satisfaction of seeing large congregations attending public services. But in 1894 the success achieved by Williams was allowed to lapse. Not until 1897 did Suva once again become the focus for the efforts of another mission worker, this time a European, Miss Hannah Dudley.

In 1896, the Fiji Synod, attempting to place the Indian Mission on a sounder basis had adopted a scheme, propounded by Worrall, for 'christianising the thousands of Indian coolies living in the Group'. Even though details of this plan are unknown it is clear that the Synod was still thinking in terms of large-scale conversion, a project which demanded a generous increase in mission staff. But the Methodist Mission Board in Australia, which was responsible for the Fiji District, remained unmoved. After Miss Dudley there was no further appointment to the Indian work for another four years.

Miss Dudley focussed her work upon the three main Indian settlements clustered around Suva. Whereas the Methodist Synod had expected concentration on direct evangelization, the activities of the missionary sister reflected concern for the needs of a neglected community. She commenced a day school for children and, at the request of a number of Indian men, opened a night school for adults. On most Sundays she visited the gaol and the hospital taking separate men's and women's services at each place. She made regular visitations of Indian homes and, with her fluent knowledge of Hindustani, achieved a marked influence among the women. 'She was called "Mai" (Mother) by the greater majority of them and was loved and revered by all'.

Ms Dudley with Indian girls

Ms Dudley with Indian girls Throughout these early years, there was violent opposition from sections of the Indian community to her ministry. According to one of her converts, the Hindus spoke secretly against her, saying 'she eats meat'. On hearing this, she turned vegetarian and lived on a strict Indian diet which gradually undermined her health. The achievements of Miss Dudley in educational and social areas of work directly influenced the course of mission policy up to and beyond 1920, though she herself left Fiji in 1912. But her efforts, although of significance in Suva, affected only a small proportion of Indians in Fiji. Their numbers were increasing rapidly during these years, notably on the western side of Viti Levu where the European missionaries in the Fijian work could do little outside of their sphere. In 1899 the Synod once again warned their Mission Board in Australia of the serious danger to which the Fijian Church was exposed and concluded that the time had now come when the Methodists should enter on Indian Mission work 'on a scale sufficiently large to make success at least probable'.

Following this appeal and the visit of a deputation from the Australian Head Office, the Indian Mission was established in 1901 as a separate administrative section under the superintendence of the District Chair-man. In one important respect the break was not complete. Control of the Indian Mission within Fiji still lay in the hands of the District Chairman, whose largest responsibility was for the Fijian Church. From 1900 to 1920 this position was held by the Reverend A. J. Small, who had been a missionary to the Fijians since 1879. In exercising his duties he brought to bear on the Indian Mission diplomacy and leadership, interlaced with the authoritarianism that had come to characterize European domination of the Fijian Methodist Church.

In addition to its change in status, the Indian Mission benefited by an increase in staff numbers. Two European missionaries were appointed, the Reverends C. Bavin and J. W. Burton, as were a number of missionary sisters, while a recruitment campaign brought catechists from India. With Burton taking over the mission work in the Rewa district, including Suva, Bavin commenced a Mission for both Indians and Europeans at Lautoka on the western side of Viti Levu.

In the spread of their Indian Mission throughout the main island of Fiji the Methodists tended to follow the largest employers of indentured labour. Nausori, on the Rewa river, was the site of one of the first sugar mills in Fiji, while at Lautoka Bavin commenced his appointment only months after the opening of the Colonial Sugar Refining Company mill. Sugar-refining centres provided a nucleus of Indians among whom the missionaries could work. Even after the completion of their indenture period large numbers of Indians settled in close proximity to the mills in order to cultivate cane and sell it to the companies. Navua, a mill centre about thirty miles west of Suva, received the attention of the Methodists after its rapid growth in the early 1900s. The Synod of 1905 noted Navua's importance as a sugar centre and two years later the Reverend Richard Piper initiated a combined mission for the English and Indian population. In 1913 a mission site was established close to the C.S.R. Company mill at Ba, east of Lautoka and four years later, when the same company offered the Methodists land at Penang in the north-east of Viti Levu, the Mission gratefully accepted.

With the exception of Ovalau, a notable feature in the expansion of Methodist Mission sites was the restriction of activities to Viti Levu. One obvious reason for this was the concentration of sugar-growing areas on the main island but since a sugar mill was opened on Vanua Levu in 1890, the reluctance of the Methodists to commence work there calls for some explanation. The Methodists were certainly not the only Christian mission body involved in evangelistic efforts among Fiji's Indian population though they possessed greater resources than the others. Both the Seventh Day Adventist and Roman Catholic churches began work among the Indians in the early 1900s, concentrating on educational facilities. The Salvation Army also indicated interest in an Indian Mission, but the Methodists discouraged these overtures. Behind the Methodist thinking lay a vague concept of the Comity of Missions, involving a delimitation of territories and 'a gentleman's agreement among the missions not to work in the territory where another mission was already established'.

The 'gentleman's agreement' with regard to the Indians was decided between the Methodists and the Anglicans. An Anglican visitor to Fiji in 1901 recalled a discussion with Methodist missionaries over the question of evangelizing the Indians. 'I can remember it was felt to be more or less an open question as to whose duty it would be'. Only one year later Lautoka was proving the hunting ground for Burton from the Methodist camp and the Reverend H. Lateward of the Church of England. The latter, according to Small, had claimed 'Lautoka, Ba and I don't know how many other places'. The Chairman coolly added that the Methodists were jumping the Anglican claims. It comes as no surprise that Cyril Bavin was placed in Lautoka as soon as possible, for had he not been the opportunity would have disappeared. In 1904 Lateward turned his attention to Labasa, but whether this was at the direct instigation of the Methodists is uncertain. Once the Anglicans were established there, the Methodists respected their claim. Indeed Small noted some years later that there was a tacit understanding that the Methodists should leave Vanua Levu to the Anglicans.

Membership of the Indian Mission grew slowly. Methodist records showed an increase from seven in 1902 to 72 in 1910 and 125 by I920. Official returns, as seen in the following table, are more conservative :

Numbers of Declared Indian Christians in Fiji

Roman Church of Christians:

1911: 33

1921: 44

Church of England:

1911: 23

1921: -

Methodists:

1911: 16

1923: 70

Others:

1911: 4

1921: -

Christians (so stated)

1911: 238

1921: 596

Total:

1911: 314

1921: 710

The most obvious explanation for the discrepancy between church and government records lies in the comparatively large number of Indians who stated their religion in each census as 'Christian'. The Methodists would have wished to lay claim to some of these signatories and indeed must have done so in their own returns. But any desire to inflate their numbers was unnecessary. According to the government figures the Methodist following increased four-fold while the Roman Catholic church experienced only a moderate improvement and the Church of England membership fell away dramatically. Whichever way the above statistics are interpreted, one clear fact is the small percentage of Indians who were converted to Christianity during this period. In 1911 it stood at 0.75% of the Indian population, and it rose only slightly in the next ten years. It is clear that the influence of Christianity on Fiji's Indians was minimal.

Disappointing as results were, it is difficult to see how the Methodists could have achieved greater success. The mission staff approached their task with great enthusiasm. As senior missionary, Burton placed great emphasis on the importance of preaching, claiming that nothing could really 'uplift the degraded Indian save the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ'. Bavin supported this view arguing rather ingenuously that it was by the 'foolishness of preaching that the subtle Hindu' was to be won. Once the problem of gaining access to the indentured labour 'lines' had been solved, and this came only after a stubborn fight by Burton, the missionaries regularly visited these centres of population.

They would usually preach in the 'lines' on Saturday afternoon or Sunday when the Indians, having been released from work, would frequent the makeshift bazaar to purchase supplies and the occasional luxury. With a box on which to stand in one hand and a Bible in the other, the missionary would choose an advantageous position close to the bazaar. There was no difficulty in gathering a crowd; missionaries were more worried about the kind of impression that their preaching might have. Usually they gained a good hearing but criticisms and interruptions were frequent and a seemingly attentive audience could be lost through the timely comments of a Hindu priest: 'The words of the sahib are true — very true. There is only one religion in the world — it is the religion of all good men, no matter whether they are Christian, Hindu or Mussulman. There are many paths: they all lead to the same place. The circumference has a million points: the centre one'.

The mission staff were not reluctant to circulate among the more widespread villages of non-indentured Indian population. Bavin would make launch trips to many of the settlements situated along the banks of the Rewa river. At each village, services would be held and house-to-house visitations would follow. Burton made even longer journeys. He would leave on a Saturday for a certain district, visit a number of villages, camp down for the night in the home of a local Indian and continue his trip to return to Nausori in the evening. Spiritual tracts would be distributed among the people and Burton was generally well received. Indian catechists, who possessed a natural advantage with their fluent grasp of the vernacular language, played an important part in evolving methods of evangelism. Their numbers fluctuated throughout the period and there were numerous problems with recruitment and employment, but quite a few schemes owed their existence to the work of the catechists. One of the most promising developments was the use of the school chapel, a one-roomed building used for school purposes during the week and for religious services on Sunday.

Erected in strategic centres such as Sigatoka, Nakaulevu, Sabeto and Penang, it was hoped that the catechists would eventually become 'the guide, philosopher and friend of the settlers about him'. In many cases, such expectations did not eventuate. Yet individual catechists exercised a remarkable influence in their particular area of work. Samuel Sharan was noted for his exposition of Christianity in debate with the leading exponents of Hinduism and Islam; it was said that crowds of over 500 would regularly gather to hear him speak. Other catechists such as John Lalu and Ishwari Prasad were a marked influence on various members of their congregation; H. S. Deoki, a prominent merchant and landowner in Suva, was converted largely as a result of Prasad's preaching.

Where their endeavours proved successful, the missionaries demanded an evident change in character as well as in belief before converts were admitted to baptism. The Indian Mission was in no haste simply to make Christians. They drew a distinction between 'head-knowledge' of the gospel and that of the heart. This interpretation was a classic example of the Wesleyan ideal of conversion whereby the convert became 'serious in his religious studies, attended all the means of grace and instruction, adopted the practice of regular prayer and eventually showed by his changed way of life that he was a regenerate soul'. Although their outlook on conversion reflected that of the early missionaries in Fiji, the Indian Mission staff received regular criticism of their methods, notably from fellow missionaries in the Fijian church.

The latter were adamant that the Indian work was being tackled in the wrong way. They spoke vaguely of the need for fewer demands on human effort and more requests for divine intervention. As one missionary expressed it, 'we can't work up a revival in the Indian Mission, it must be worked down from heaven'. Burton and Bavin as senior members of the Indian Mission were unimpressed by such remarks. They argued that the different traditions and cultures of the Fijian and Indian, indeed the different levels of human evolution, precluded any valid comparison of mission methods: 'The Fijian was a simple-minded man with a child's intellect .... There was strong moral resistance to the message but no mental opposition . . . . But the Christian Church in these Islands has an entirely different class to deal with in the Indian .... He is acknowledged to be one of the most subtle and acute thinkers the world has known .... Thus in addition to a moral resistance, we have to be prepared to face a mental one of the strongest and most unyielding sort.

Burton reflected the majority view of the Indian Mission staff in believing that Christianity provided a far more satisfactory alternative for the Indian than either Hinduism or Islam. He frequently drew attention to the prevailing immorality within the immigrant community, especially the numerous murders and assaults provoked by the scarcity of women; only the high ethical qualities and demands of the Christian religion could supply the moral incentive needed to overcome the alleged depravity of the Indian people. Some missionaries directly attributed this immorality to elements within the Indian religion. W. R. Steadman was convinced that low ideas of morality were inherent in what he termed 'popular' Hinduism. 'It is in India that the low moral tone is first found. . . . The work that lies before us is that of incul-cating the higher moral ideals of Christianity'.

Most missionaries recognized that the indenture system led to a decline in morals but contract labour merely accentuated the existing evil; a final solution could only come with the 'displacement of Hinduism by Christianity'. The most disappointing aspect of this mission outlook was its restriction to a superficial acquaintance with religious practices that prevailed in Fiji. Missionaries who visited India soon appreciated the qualities that had been lost as a result of the four thousand mile journey and the indenture system. When travelling through Fiji in 1915 the Reverend C. F. Andrews, a respected missionary from India, was reluctant to conclude that the apparent decline in morals could only be arrested by acceptance of Christianity: 'On every hand we found a longing for instruction to be given in religion, and this clearly proceeded from a pure desire, that the children of Hindu parents in Fiji should not lose all knowledge of their ancestral faith . . . . Here is the crux of the whole position. Until religion is re-established in the hearts of the people, the basis of Hindu social life is radically unsound.'

As the Indian Christian church grew it came to reflect the diverse background of its adherents; there were capable members who were originally from the northern provinces of India but generally speaking the Methodists found a more favourable response among the South Indians. This group was not drawn into the indenture system until after 1900 but, having inherited a longer tradition of Christian contact (starting with the Portuguese in the mid-sixteenth century), they gave a much-needed stimulus to the Indian Mission. According to one missionary they were 'not so self-satisfied . . . more open to reason, and quicker to respond to the appeal of the Gospel'. It is interesting that this division was also apparent in a social level. Writing ten years after the end of indenture the Reverend L. M. Thompson noted that the Indians of northern origin held comparatively good positions in the community and were intellectually and socially higher, while the South Indians were mostly labourers or house-servants and had a great love for their church, giving generously to it 'within their limited means'.

There was a sprinkling of most Hindu castes in the family back-ground of such members. Samuel Sharan, for instance, came from a high caste Hindu family. As a young man he had left his kin in India and thus was probably more receptive to Christian influence than if he had emigrated to Fiji with his family. Certainly the latter disapproved of his conversion, for when he returned to India his parents were prepared to offer him assistance only if he reverted to Hinduism.36 Such a reaction was common in India and Fiji. Among the lower caste groups there was a significant contrast in their response to Christianity between India and Fiji. In the former country the release from caste restrictions which the Christian gospel offered produced an influx of 'untouchables' and low-caste Hindus into the mission churches of India. This situation had little relevance to Indian society in Fiji. Emigration and inden-tured labour had nullified the more binding aspects of the caste system. The implications of this change were accurately noted by a visitor to Fiji in 1913: 'In India, thousands of low-caste people will listen to the missionary's message, because of the social emancipation it involves; but in Fiji, the Bhaingi (scavenger) and the Brahmin eat together, and the Bhangi may have a high-caste woman for his wife. This means that the low-caste Indian in Fiji will not consider the claims of Christianity on account of the freedom from social disabilities it may offer, as he would if in his native land.'

One cannot but observe, in discussing the Indian Christian, that most of the mission converts were originally of the Hindu faith. The Methodists found that the Muslims were invariably more hostile towards the missionaries, a situation which the Baptists had experienced in India some seventy years earlier. The Muslim community was more militant and forthright in its religious proclamation. They regarded themselves as a missionary-motivated organization which, compared to the calm nature of Hinduism, was 'turbulently aggressive and flushed with the confidence of victory'. Muslim leaders even boasted to Burton that they would yet convert the Fijians from Christianity to Islam. In cases where Muslims were converted to Christianity they were never free of persistent attempts by members of their former faith to persuade them to return to the Islamic tradition.

W. R. Steadman, many years after his service in Fiji, recounted the following incident involving a Muslim shopkeeper, Wali Mahomet, who had decided to receive baptism: 'The day he was to be baptized at the service, a number of leading Moham-medans attended together and ominously took their places in the front seats. After the opening of the service Wali rose to make his confession of faith. Speaking to the Mohammedan deputation in front of him he said, 'I know why you have come here today. You intend to prevent my baptism at this service. There are sufficient of you to do this. But if you forcibly take me away today, I will come back some other day to receive baptism. Even if you were to kill me I declare that I have already been baptized in my heart and have received acceptance with God through Jesus Christ my Lord and Saviour. You cannot alter my belief in Jesus Christ even if you physic-ally prevent this baptism. Now, here I am, what will you do?' Whilst he stood there before them waiting, not one of them moved, and the baptismal service proceeded quietly in their presence.'

Wali Mahomet later went bankrupt through boycotts imposed by the Muslim community and this worry brought about a fatal illness. How-ever, few were as courageous as he. Steadman has claimed that in the first years of Indian work there were increasing numbers of undeclared believers who publicly retained their original belief 'because community and family conditions made it almost impossible to do anything else'.

Probably the greatest difficulty in studying evangelization among the Indians is to discern motives for conversion. Expediency cannot be excluded, but it distorts the picture to draw conclusions from isolated examples such as an indentured Indian, Badri, who was prepared to be converted if the Mission could obtain his release from indenture. Certainly some Indians accepted Christianity for purely material reasons, the so-called 'rice Christians'. This occurred notably in Navua during the 1920-21 disturbances when there were serious shortages of food. Other Indians wished to gain for their children the precious educational opportunities which were offered by the Mission, though it should be noted that the Methodists opened their schools to all Indians regardless of their religious beliefs. Again a few converts were attracted to Christianity by employment opportunities, particularly in the field of teaching.

Despite these factors however, the small number of Indian Christians by 1920 clearly suggests that any material fruits which were offered by the Methodists were not worth the cost of conversion; that cost was often so great that it leaves little room for doubting the sincerity and conviction of those who were converted. The increased status or benefits of the white man's religion, if they did exist, must be weighed against the fact that an Indian practically gave up his very tradition when he chose to lay aside either Hinduism or Islam. He was, in many cases, rejected by the majority of his compatriots and significantly referred to not as an Indian, nor even as an Indian Christian, but merely as a 'Christian'.

In their attempts to justify the spending of large sums of money on work amongst the Indians, mission writers have tended to lay stress on Methodist activities in the fields of education and welfare rather than examine the reasons for failure of direct evangelization. In general, the Indians expressed their indifference, intolerance and, even at times, hostility towards the preaching of Christianity not so much because of the concepts of the Christian gospel but as a reaction to its exponents and the culture they were part of. It was not the Word which offended but the Flesh. In addition, as Burton perceived, the Indian community regarded its own religious practices as entirely adequate for its needs. Yet even he remained hopeful that the Christian missionary could exert a reflex influence. 'The effect of the preaching of the gospel is to make the Hindu and Muhammedan each emphasize the ethical and spiritual side of his religion and place less importance upon the ceremonious and superstitious'. Independent-minded missionaries like C. F. Andrews went further; there was no need for any ultimate clash between two religions such as Christianity and Hinduism which, having so much in common, should help and strengthen one another.

The Methodists would no doubt have rejected Andrews' comments. To them the issue was quite straightforward: where Hinduism or Islam prevailed the Christian spirit could not be present. Thus, in an effort to increase their influence, the Indian Mission turned to its growing number of schools. Education as a branch of mission work did not come into prominence until after 1910 though its potential was recognized much earlier. Williams had wanted to start a school but was hindered by his seniors who did not wish to see him confined to one place. Miss Dudley had spent much of her time establishing two schools in Suva and further buildings were erected in other main centres. Teaching in the schools was entrusted to missionary sisters and catechists though, when staffing shortages occurred, the superintending missionaries often had to step in to prevent schools from closing.

The early years saw a struggle to keep schools open and maintain pupil numbers but by 1911, 414 children were receiving instruction in six Methodist Indian schools on Viti Levu, a number which represented about 7.8% of school-age Indian children.43 Small as this figure may seem, the fact was that the Methodists were more deeply involved in Indian education than any other organization. The Seventh Day Adventists and the Roman Catho-lics each opened a school in Suva, and the Anglicans operated a school at Labasa, but these catered for smaller numbers. To the Methodists must go the major credit not only for providing the initial impulse towards provision of basic education requirements for Indians but also for their part in urging the government to assume greater responsibility. For many years the colonial authorities showed a singular lack of interest in Indian education (a reflection partly of European opinion) and were seriously embarrassed by the report of a Commission in 1909 which commented on the unfavourable facilities available. Not for a further seven years did the government take some action and agree to enter into a grant-in-aid scheme, which did not prove as generous as the Methodists had hoped.

From 1910 to 1916, a courtship of convenience developed between the Methodists, seeking additional finance to expand their educational schemes, and the sugar companies (particularly the C.S.R. Company), prodded by the government into providing schools for the children of indentured labourers. The Methodists were eager to locate boarding establishments alongside their schools but the extra finance needed to achieve this was beyond their means. It was at this point that the com-panies came to the rescue. Not wishing to incur unnecessary costs, they made tantalizing overtures of monetary support to the Methodists. In 1915, after prolonged negotiations with the government authorities, the sugar companies were released from their obligation to build schools, being required instead to donate £300 to the Methodists for the exten-sion of education services at each of their mill sites, together with a subsidy for each child from their estates who attended the schools.

Methodist reaction to the agreement was overwhelmingly favourable. The finance available would enable them to cater for more Indian students (an increase from 465 in 1915 to 610 in 1916), while in the longer term their hold on this field of education would be strengthened. The fact that mission ties with the sugar companies were now closer was of little concern. Small, the Methodist Chairman, adequately summarized the attitudes of most mission workers : 'The only reason that has influenced us in offering to take over the Indian children from the Sugar Companies is this; that thereby we have given to us an opportunity of winning these children to Christ. Let us suppose that the Sugar Companies provide their own schools and school teachers. Would not we, in that case, lose our chance of influencing them after they had been under their pagan teachers for five years?'

Small's question suggests why the Methodists sought to become in-creasingly involved in education: members of the Indian Mission believed that their schools represented the greatest hope for permanent Christian influence.

This was a basic mission aim. The Baptists in India for instance did not hide the fact that their schools were established 'in the hope of leading Indians to embrace Christianity'. This was why they had come to India. In Fiji it was no different. 'These children', wrote one missionary, 'ought to be saturated with the teachings of Jesus.' Richard Piper, another missionary, was convinced that if the Methodists could expand their school in Lautoka, it would be a great means of obtaining a hold on the young Indian in Fiji. 'We have a fine crop of youngsters coming into our schools and it is my cherished ambition to seize this splendid opportunity'.47 Some missionaries, however, were too confident about the role of mission schools. L. M. Thompson visualized a system of primary, secondary and tertiary education which would eventually create a new Indian state and a new system of morals. 'Our faith is that there will arise an India in Fiji that shall not be unworthy to take its part in the City of God!'

Despite assertions that day schools were a powerful influence on those attending them there is very little evidence to sustain this argu-ment. Church statistics suggest a pattern to the contrary. In the eight years from 1908 to 1916 the number of scholars in Methodist schools rose from 116 to 610. But in the next eight years, with commencement of the government grant-in-aid scheme and with the opening of a num-ber of new schools, the increase of just over 400 pupils was smaller than hoped for. Church membership figures reflect this trend. From 1908 to 1916 numbers grew from 39 to 111. Yet in the following eight years only a further 60 were added to the roll. There were also signs towards the close of the indenture period indicating the Indians wanted to establish their own schools rather than rely on mission institutions. The Inspector of Immigrants at Ba, when reporting on a small Indian school in his area, noticed that the aim of the school appeared to be 'the education of Indian children, avoiding all Christian influences'.

The two visits of C. F. Andrews in 1915 and 1917 helped to spark off a self-help programme among Indians and money was raised by members of the community with the intention of commencing Indian schools. Andrews pointed out that it would be a mis-take on the part of the government if the latter chose to place all education in the hands of the missionaries: 'We had abundant opportunities of reaching the real opinion of the Indian community in Fiji, and we were certain that such a policy would be looked upon as a very serious infringement of the principle of religious neutrality. If the Fiji government were simply to stand aside and distribute grants-in-aid, the missionary societies would be certain to step in and reap all the financial benefits. This would give the whole Indian education of the Islands a predominantly Christian colour even though the Indian parents might wish their children to be educated in their own Hindu and Musulman precepts.'

It is of little surprise that Andrews was able to grasp the mood of the moment; no missionary in the Indian work reflected the aspirations of Fiji's immigrant community to the extent that he did. Andrews is best remembered in Fiji for the part he played in ending the indenture system. Less well-known is the fact that he was first introduced to the evils of this form of contract labour by J. W. Burton. Shortly after his appointment to Fiji in 1902, Burton's attention was drawn to the deplorable conditions that existed in some of the labour 'lines'. Subsequently his concern for the plight of the indentured labourer mainly derived from an intense evangelistic approach to missionary work. From early experiences with some of the estate owners, who were inclined to be suspicious of Christian teaching in the 'lines', Burton became convinced that the greatest obstacle to the progress of Christianity was the existence of the indenture system. Thus he was careful to point out that the commentary on indentured life (which virtually demanded abolition of the system), was included in his book, The Fiji of Today (1910) for one major reason: 'to save Fiji and bring about the Kingdom of God'.

The Methodists have been proud to call Burton and his book their own, but with little justification. If Burton gave a lead in attacking aspects of the indenture system, the Indian Mission and the Methodists as a pressure group groped for a policy that would somehow satisfy everyone and offend no one. Though Small privately expressed a high opinion of the book, its publication was greeted with such a public outcry, including letters of criticism from the Governor, that the Methodist Synod was compelled to issue a statement dissociating itself from any involvement with or responsibility for the printing of the book. During the next three to four years the attitude of the Methodist Mission became even more conservative. The senior missionary in the Indian work after the departure of Burton (who had left Fiji well before his book was published) was Cyril Bavin, an active supporter of indentured labour; he claimed on one occasion that as a result of the in-denture system the Indian invariably improved 'mentally, physically and morally'.

When the Reverend Richard Piper, while on a visit to India in 1914, proposed the abolition of the system, both Bavin and Small quickly denied that Piper's views were in any way endorsed by other members of the Indian Mission. 'While the Methodist Mission is by no means blind to the abuses connected with the working of the Indenture System, it has never gone so far as to condemn the system on account of these abuses, believing them to be an excrescence that can be, and will be, removed'. What were the reasons for the increasing sensitivity of the Methodists? First, Bavin himself was personally involved in a business enter-prise which employed indentured Indians;54 this may partly explain why he held such strong views. Secondly, the Methodist Synod, which included the Indian Mission, was seriously considering the establishment of a banana plantation which would utilize indentured labour. It was hoped that the conditions of the plantation labourer's life would be an example of the proper working of indentured labour. In the debate that accompanied the first visit of Andrews to Fiji in 1915 this project was quietly abandoned. Probably the most telling factor in shaping Methodist attitudes on indenture was their negotiations with the sugar companies over arrangements for education. In 1915 discussions on handing over responsibility to the Mission had reached such a delicate stage that Bavin had to make a special trip to Sydney to meet Edward Knox, general manager of the C.S.R. Company. The latter informed Bavin that internal opposition to company assistance for the Methodists was based on disapproval of views on the indenture system expressed by Burton and Piper.

When Bavin pointed out that the Methodists had publicly dissociated themselves from the opinions of these men, Knox 'came right round splendidly and said, "Well, is it only the extra land you want, or are you asking for financial assist-ance?" Obviously the Indian Mission was not prepared to imperil its ties with the sugar companies if it meant losing increased material aid for education. Because of the views they held most of the missionaries were de-cidedly cautious in their approach when Andrews made his first visit to Fiji, though many of them accommodated him on his travels around Viti Levu. Two years later circumspection had given way to open sus-picion and a series of criticisms were levelled at the nature of Andrews' activity in Fiji. McDonald, missionary at Ba, was quite unimpressed with Andrews, and claimed that his role as an 'unattached agitator' was doing less good than if he had remained an orthodox missionary.

W. R. Steadman, superintendent of the mission in Suva, argued that Andrews' close association with the 'Home Rule for India' party automatically placed him in a suspicious light. To identify the Mission with the ideals and methods of such a political movement was doubtful policy for the Australian Methodist Church. Steadman also accused Andrews of sowing seeds of discontent among the prisoners of Suva gaol: according to reports from an Indian warder, Andrews used the opportunity to conduct a service at the gaol to outline the purpose of his visit and to inform the prisoners that 'they were more sinned against than sinners and were the victims of the white man's avarice'.57 While the majority of Indian Mission members agreed with the sentiments of McDonald and Steadman, a small number recognized the failings of the Methodists in not speaking out when the opportunity had arisen. Apart from Piper, there was C. O. Lelean who believed that the Mission had concentrated more on work amongst individuals than in any states-manlike attempt to ameliorate the condition of the people as a whole. '1 feel somewhat jealous to think that Mr Andrews and Mr Pearson appear to have done more towards the abolition of the system in the short time during which they have had the matter in hand, than our Mission has done from the time when it first recognised its responsibility with respect to the Indians in Fiji'.

The Indian Mission had been seriously divided over the indenture issue. It was not as though they were in the front line of forces for change; indeed it was the reverse. When defending mission policy before the Board of Missions in 1918, Small had tried to vindicate his action by hiding behind the efforts of Burton and Piper. Yet, by the time Bavin had departed in 1916 and the Mission was sufficiently united to press for limited reforms, complete abolition was only a question of technicalities. Burton and Piper were reflections of a transforming current, centred in India, with which the Methodist Mission was hopelessly out of touch.

The history of the Indian Mission after 1892 is one of changing emphases. In the first two decades to 1910, the emphasis was primarily one of evangelism, with J. W. Burton shaping mission policy according to his own convictions. 1920 comes in the middle of the second period when, under the influence of Bavin, educational and welfare work supplanted the preaching of the Gospel as the major daily concern of mission staff. The focus of attention in this second period shifted from the older to the younger generation and methods of operation altered accordingly. Very few missionaries would have admitted that there had been a shift in emphasis at all. It was not an argument of exclusion — evangelization or education. They still regarded the former as their main aim and any other activity as a means to that end.

However, in turning to schools as an important agent of Christian influence, the Methodists filled an embarrassing gap for the government at a time when the demands of Indian education were first being felt. In assuming this responsibility the Methodists bit off more than they could chew and found themselves sacrificing the evangelistic outlook of the early years for a more functional role. It was not till the late 1920s that the first challenges to this phase of mission work came from an ardent and disillusioned group of Indian Christians.