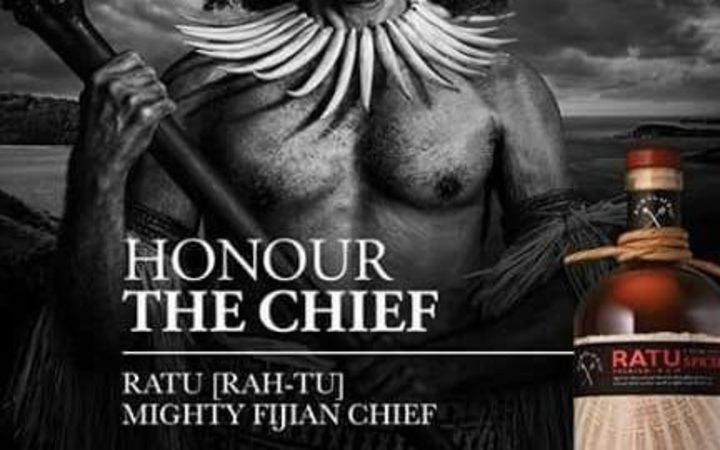

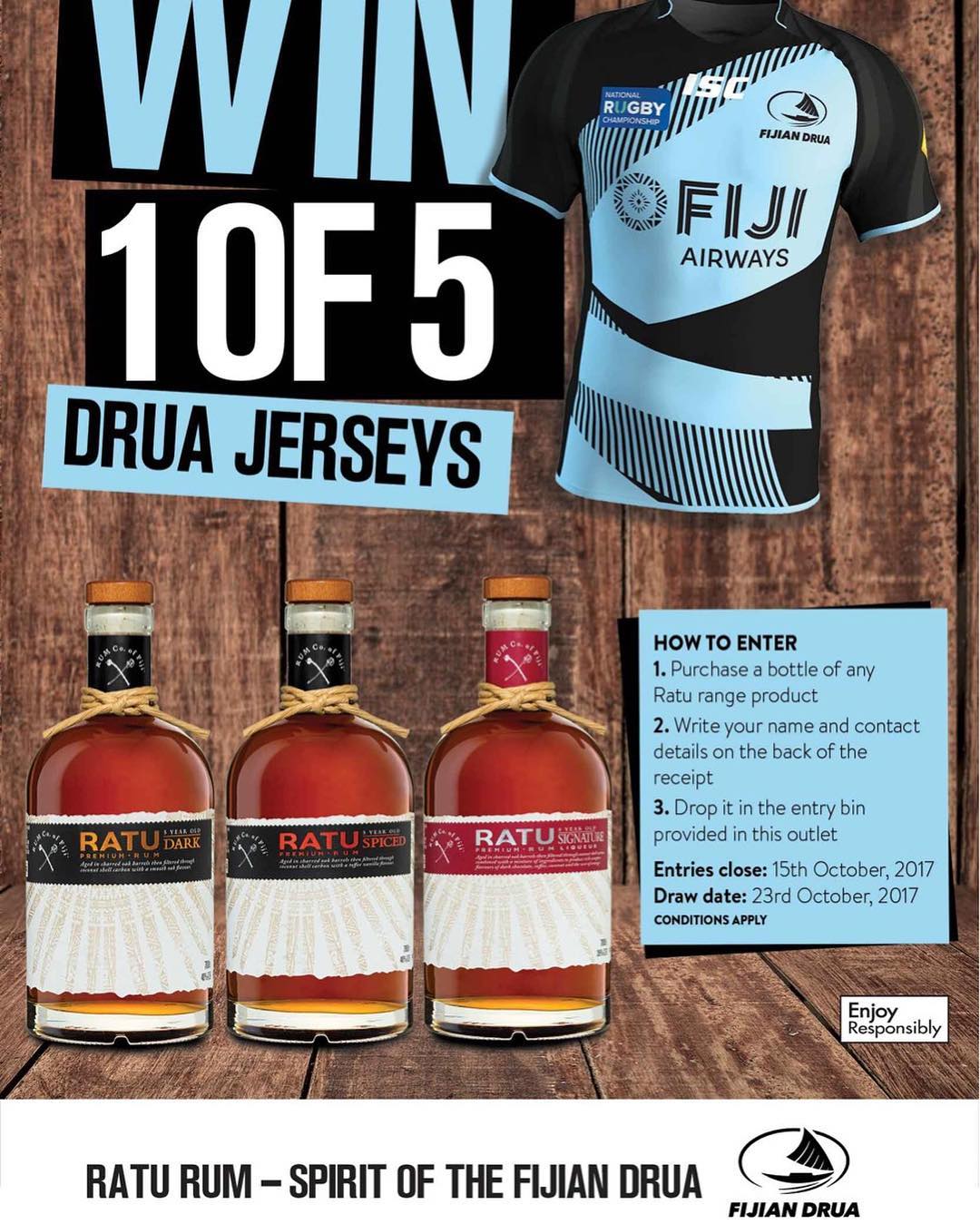

Shiri Ram says a major beverage company, Paradise Beverages and Fiji's branch of the global giant, Coca Cola Amatil, is selling alcohol whose name disrespects local Fijian chiefs and culture. Ram, in an interview with Radio New Zealand, said while the drink was not new it was initially launched as Ratu's Rum with the blessing of an individual chief.

"Now the title has move[d] from the chief to the product, so you know, to say that a bottle of alcohol is now been titled a Ratu is open to all sorts of interpretations but none of those interpretations lead to anything good." Shiri Ram said the companies also sells Bati Rum, which is

Fijian for warrior

http://www.radionz.co.nz/audio/player?audio_id=2018620379

What's in a name? A Chief drink in Fiji called 'RATU RUM'

"Fifteen men on the dead man's chest--

...Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!

Drink and the devil had done for the rest--

...Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!"

Robert Louis Stevenson, Treasure Island

Fijileaks: The name RATU RUM has been around for a while and yet we have not heard a word of protest from SODELPA MP Niko Nawaikula, who always gets punch drunk whenever the debate is on the usage of the word FIJIAN, claiming that the identity of the indigenous people is being taken away by calling all citizens of the country, Fijians. What about the word RATU? Isn't the revered title being stolen from his Chiefs?

Lets drink a glass of RATU RUM and turn into HAPPY BUM BUM:

YO-HO-HO AND A BOTTLE OF RATU RUM!!!!!!!!!

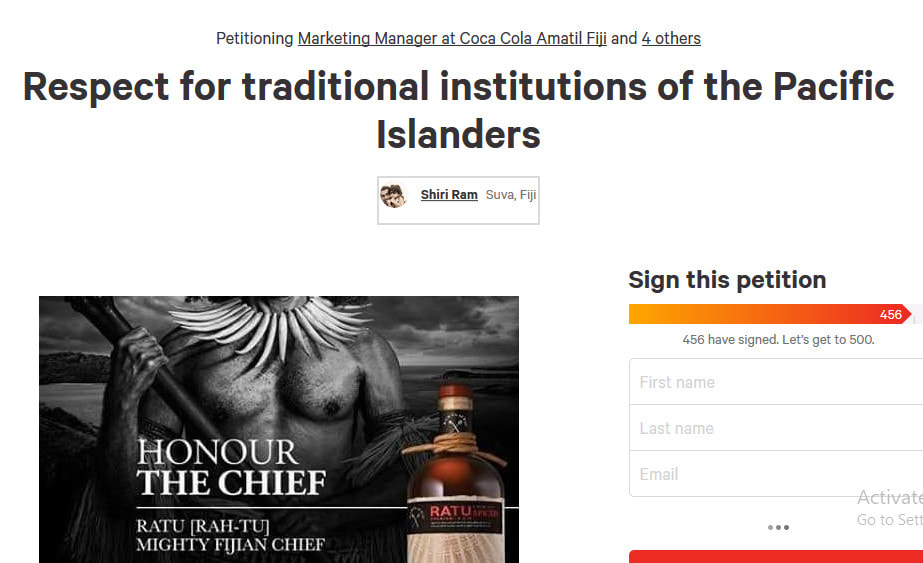

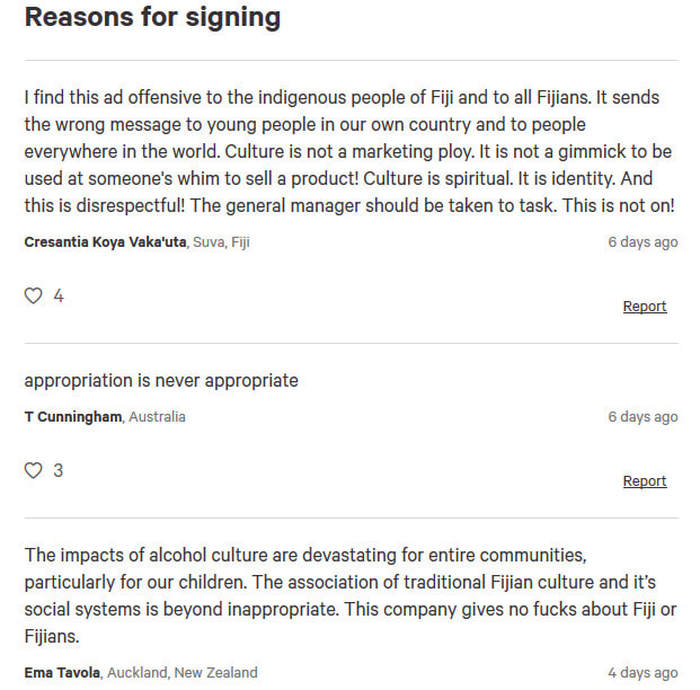

Shiri Ram's petition has so far gathered over 456 signatures:

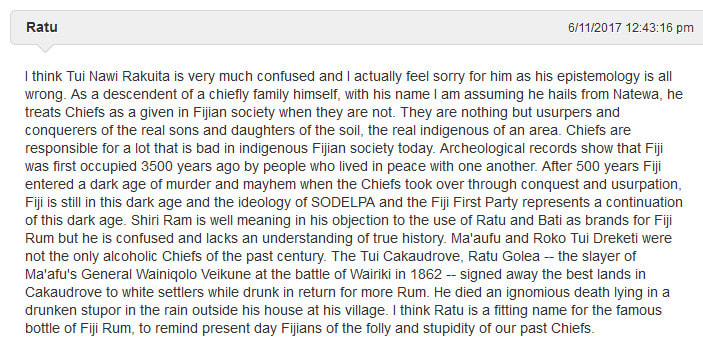

Paradise Beverages in collaboration with Starwood Resorts produces a line of alcohol called "Ratu Rum"and "Bati" (i-Taukei word for warrior). A new advertising campaign created by a New Zealand creative agency is currently trying to sell the alcohol by creating links between the alcohol and i-Taukei Chiefs and i-Taukei warriors.

This is gross disrespect to the i-Taukei institution of chiefs and warriors and reduces these institutions to the level of alcohol. The purpose of this petition is to bring to the attention of all parties concerned that the Fijian/Pacific people do not approve of their institutions, culture, and tradition being used to sell alcohol.

The purpose is also to raise awareness of traditional institutions within the Pacific and respect for them. Below is my take on the advertising campaign and names used: "Ratu, to the best of my knowledge, is the title of a chief and is uttered in respect for the person who holds the title.

While growing up as a non-iTaukei I was told that the Ratu is the Raja (King) of his land and is to be respected as such. This same respect is now demanded towards a bottle of alcohol. The very same poison that has plagued numerous ills in our society, and families, now carries the importance and respect of the person who is a leader.

Being in the marketing/advertising industry for a number of years I must say this is one of the most degrading forms of advertising that I have seen. To use the title that carries cultural and traditional significance and one that is deep rooted and still plays a part not only in the lives of the i-Taukei but the whole population of Fiji, just to sell a bottle of alcohol lacks any form of creativity or thinking.

The names behind this are the Starwood Group of Hotels, Paradise Beverages and Creative Method (The advertising Agency). All 3 foreign owned companies that reap the benefit of dragging a high institution of the i-Taukei way of life into the gutter with absolute disregard. Chiefs and warriors (Bati range of rum) of Fiji are now sales people for selling alcoholic drinks produced entirely by foreign owned companies who couldn't care less to accord respect and dignity to Fiji.

This is in indeed the same mentality that came with razor blades to buy land and sandalwood. Sadly it still exists. Sadly we allow it to exist."

This petition will be delivered to:

https://www.change.org/p/marketing-manager-at-coca-cola-amatil-fiji-respect-for-traditional-institutions-of-the-pacific-islanders

This is gross disrespect to the i-Taukei institution of chiefs and warriors and reduces these institutions to the level of alcohol. The purpose of this petition is to bring to the attention of all parties concerned that the Fijian/Pacific people do not approve of their institutions, culture, and tradition being used to sell alcohol.

The purpose is also to raise awareness of traditional institutions within the Pacific and respect for them. Below is my take on the advertising campaign and names used: "Ratu, to the best of my knowledge, is the title of a chief and is uttered in respect for the person who holds the title.

While growing up as a non-iTaukei I was told that the Ratu is the Raja (King) of his land and is to be respected as such. This same respect is now demanded towards a bottle of alcohol. The very same poison that has plagued numerous ills in our society, and families, now carries the importance and respect of the person who is a leader.

Being in the marketing/advertising industry for a number of years I must say this is one of the most degrading forms of advertising that I have seen. To use the title that carries cultural and traditional significance and one that is deep rooted and still plays a part not only in the lives of the i-Taukei but the whole population of Fiji, just to sell a bottle of alcohol lacks any form of creativity or thinking.

The names behind this are the Starwood Group of Hotels, Paradise Beverages and Creative Method (The advertising Agency). All 3 foreign owned companies that reap the benefit of dragging a high institution of the i-Taukei way of life into the gutter with absolute disregard. Chiefs and warriors (Bati range of rum) of Fiji are now sales people for selling alcoholic drinks produced entirely by foreign owned companies who couldn't care less to accord respect and dignity to Fiji.

This is in indeed the same mentality that came with razor blades to buy land and sandalwood. Sadly it still exists. Sadly we allow it to exist."

This petition will be delivered to:

- Marketing Manager at Coca Cola Amatil Fiji

- Marketing Manager at Paradise Beverages

- Marketing Manager at Starwood Resorts

https://www.change.org/p/marketing-manager-at-coca-cola-amatil-fiji-respect-for-traditional-institutions-of-the-pacific-islanders

April 2015: Voreqe Bainimarama (left) and Alison Watkins, managing director, CCA Group Coca-Cola Amatil Limited, are taken on a tour of the new plant at Paradise Beverages with guests in Suva

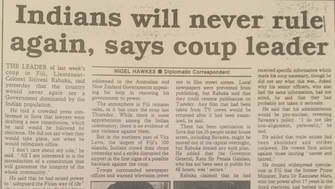

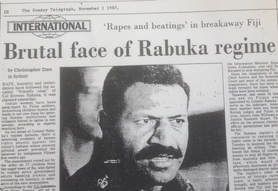

A NOTE FROM HISTORY: While Shiri Ram is absolutely within his rights to launch the petition, alcoholism among some of the native Fijian chiefs was rampant, the two most notorious to be chided were Ma'afu and the Ratu Tui Dreketi, who was a notorious alcoholic. In the November 1880 Great Council of Chiefs [Bosevakaturaga] proceedings, the Roko Tui Bua addressed the gathering chiefs, admonishing the two as follows:

"There are two amongst us whose habits of drinking are notorious. One is Roko Tui Dreketi, the other is Roko Tui Lau. Who are they, and what are they? Are they great and valiant men that their habits are thus? They are but men like ourselves .... Both these chiefs have been spoken to, counselled, and admonished, but they follow their ways, the fruit of which they do not eat alone – we are all sharers in their reproach and shame. It is unlawful to take ... a person out of prison under sentence ... Roko Tui Lau ... did so in Levuka, and what was the result? None of us are devoid of sympathy and the desire to help his fellow, all of us have our failings and weaknesses, but if we are chiefs and are called upon to fill our positions in the government of our people, the faithful discharge of this duty surely ought to be our object"

Anointing of a chief

By Dr Tuinawi Rakuita

The Fiji Times, Tuesday, October 24, 2017

The author, Dr Rakuita, says new ways of installing traditional chiefs disenfranchises groups within the vanua which historically have been tasked with performing certain ceremonial roles in any installation

By Dr Tuinawi Rakuita

The Fiji Times, Tuesday, October 24, 2017

The author, Dr Rakuita, says new ways of installing traditional chiefs disenfranchises groups within the vanua which historically have been tasked with performing certain ceremonial roles in any installation

Dr Rakuita of USP

Dr Rakuita of USP IN the heyday of European monarchs and aristocrats, religion was seen as a powerful legitimation tool. Kings and queens would go out of their way to consort with the representatives of the church in an ongoing attempt to legitimise their positions both in heaven and on earth.

Failure to do this would put them at considerable risk of being sanctioned by, as it happened, the Roman pontiff. In fact the links between royalty and divinity goes back into the murky depths of history and are, on the main, embedded within the socio-political embroidery of most societies. Taukei communities are no exceptions to this.

When the Wesleyan and, later, Catholic missionaries first arrived on our shores, their first converts were usually chiefs. The idea behind this strategy was that it would facilitate the spreading of the gospel throughout the vanua in the quickest possible way. It worked.

Those who resisted were often coerced by the new converts, with the backing of the new colonial state, into submitting to the new religious order. Reverend Dr Andrew Thornley, in a recent publication, summed up that transformation as nothing less than A Shaking of the Land. The i Taukei translation, Na Yavalati ni Vanua, in my view is more apt such was the nature of the transformative changes demanded by the new religion.

The ramifications of that development are still being felt today in a myriad of ways as the i Taukei communities seek to integrate the principles of the lotu with the customs of their respective vanua. As such, we are increasingly witnessing the presence of religious representatives in the installations of vanua chiefs throughout Fiji.

Initially, the role of these representatives of the church was to bless the covenant, symbolised by all installation ceremonies in the country, between the chiefs and their people. The adage that all chiefs are from God is, in such contexts, simply a validation of the consensual transfer of authority from the vanua to the chiefs.

The status of chiefs, therefore, hinges on the willingness of the people to perform certain roles within their respective vanua. In other words, if it is true that all chiefs are from God (Turaga sa mai vua na Kalou), it is equally correct to suppose that a chief cannot operate with authority without the expressed agreement of the vanua and its people.

This is a reminder that i Taukei chiefs rule primarily via consent. Without this consent, the concept of an i Taukei chief becomes nonsensical. As such, it is the substance of all chiefly installations within the different vanua in Fiji.

Yet lately we have been witnessing a not too subtle move to reverse the order of precedence among the primary stakeholders in the making of a vanua chief. This is probably the result of widespread changes running through i Taukei societies today.

Urbanisation and globalisation, together with their corollaries, have generated new ideas on a number of issues including ones pertaining to leadership. This has been exacerbated by the severing of the institutional ties, forged by Sir Arthur Gordon, between the chiefs and the state.

As a consequence, vanua chiefs have lost the political clout afforded to them under previous governments as the current state engages in a form of social engineering that is informed by its own ideas of inclusivity. This new development may have given rise to the view, among chiefs and commoners alike, that the vanua is increasingly losing its mana.

As a result, an ambivalent mood within i Taukei communities has fuelled the search for a firmer grounding of chiefly authority. This partly explains why new ways of legitimising vanua chiefs have gained considerable currency in contemporary i Taukei communities.

The installation of the latest Tui Nadi is a case that will have far-reaching implications on the way chiefly authority is conferred within i Taukei society. It raised more than a few eyebrows within the Yavusa of Navatulevu as vanua protocols were, presumably, ignored in favour of religious ones.

Rt Vuniyani subsequently brushed these reservations aside by insisting that since his legitimacy has been legally established and recognised by the state, the specific way he was made a chief is really a matter of personal consideration.

As it turned out, he was anointed to his position as Tui Nadi by several church ministers using a prototype from the Old Testament.

What lies at the heart of this latest undertaking is the friction between the quest to integrate, in this case, Ratu Navuniyani's personal freedom to choose how he is to be installed in his vanua and the prevailing moral order of the same vanua from which he is recognised as a chief. The case for the freedom to choose, in this instance, trumped over the imperatives of the recognised social order. Does that make one a bona fide vanua chief?

My main reservation with this new way of legitimising chiefly authority lies in what I perceive as the latent suppression of the vanua as the exclusive repository of legitimate cultural authority. It disenfranchises groups within the vanua who have been historically tasked with performing certain ceremonial roles in any installation.

These roles are symbolic in that they signify the consensus of the vanua in the making of their chief. It is this symbolism that ties the chief and his/her people in an ancient custom of reciprocity. In a nutshell, the chiefs are made by the people and, thus, are ultimately answerable to them.

Yet, as the Nadi case shows, the preponderance of religious rites over customary ones in vanua installations could spell the disempowerment of the ordinary i Taukei from the making of his/her own chief.

Claiming legitimacy or authority via religious formalities brings to mind that age, in human history, where the divine right of kings was a taken for granted fact. This concept of "divine right" is associated with an overt attempt by ruling families for absolute power over their subjects. It removed the need of the European sovereigns to be accountable for their actions.

Indeed the history of European religio-feudal absolutism is littered with tyrannical accounts of enslavement by kings and cronies who claim, with the backing of the church, that their right to rule is a God-given entitlement. In instances like this, human freedom becomes an exclusive domain of the powerful in society.

The subsequent emergence of new ideologies marked by an avowed refusal to sacrifice personal freedom to political, moral and/or religious expediencies is a direct result of the need to safeguard the general population from the vices of those who wield absolute power in European polities.

If we are to protect our identity as i Taukei people and continue empowering our communities in the future, we could do much worse than heeding the historical lessons above on the corrosive impacts of unbridled power in European feudal societies.

* Dr Tuinawi Rakuita is a lecturer in sociology at USP's School of Social Sciences.

Failure to do this would put them at considerable risk of being sanctioned by, as it happened, the Roman pontiff. In fact the links between royalty and divinity goes back into the murky depths of history and are, on the main, embedded within the socio-political embroidery of most societies. Taukei communities are no exceptions to this.

When the Wesleyan and, later, Catholic missionaries first arrived on our shores, their first converts were usually chiefs. The idea behind this strategy was that it would facilitate the spreading of the gospel throughout the vanua in the quickest possible way. It worked.

Those who resisted were often coerced by the new converts, with the backing of the new colonial state, into submitting to the new religious order. Reverend Dr Andrew Thornley, in a recent publication, summed up that transformation as nothing less than A Shaking of the Land. The i Taukei translation, Na Yavalati ni Vanua, in my view is more apt such was the nature of the transformative changes demanded by the new religion.

The ramifications of that development are still being felt today in a myriad of ways as the i Taukei communities seek to integrate the principles of the lotu with the customs of their respective vanua. As such, we are increasingly witnessing the presence of religious representatives in the installations of vanua chiefs throughout Fiji.

Initially, the role of these representatives of the church was to bless the covenant, symbolised by all installation ceremonies in the country, between the chiefs and their people. The adage that all chiefs are from God is, in such contexts, simply a validation of the consensual transfer of authority from the vanua to the chiefs.

The status of chiefs, therefore, hinges on the willingness of the people to perform certain roles within their respective vanua. In other words, if it is true that all chiefs are from God (Turaga sa mai vua na Kalou), it is equally correct to suppose that a chief cannot operate with authority without the expressed agreement of the vanua and its people.

This is a reminder that i Taukei chiefs rule primarily via consent. Without this consent, the concept of an i Taukei chief becomes nonsensical. As such, it is the substance of all chiefly installations within the different vanua in Fiji.

Yet lately we have been witnessing a not too subtle move to reverse the order of precedence among the primary stakeholders in the making of a vanua chief. This is probably the result of widespread changes running through i Taukei societies today.

Urbanisation and globalisation, together with their corollaries, have generated new ideas on a number of issues including ones pertaining to leadership. This has been exacerbated by the severing of the institutional ties, forged by Sir Arthur Gordon, between the chiefs and the state.

As a consequence, vanua chiefs have lost the political clout afforded to them under previous governments as the current state engages in a form of social engineering that is informed by its own ideas of inclusivity. This new development may have given rise to the view, among chiefs and commoners alike, that the vanua is increasingly losing its mana.

As a result, an ambivalent mood within i Taukei communities has fuelled the search for a firmer grounding of chiefly authority. This partly explains why new ways of legitimising vanua chiefs have gained considerable currency in contemporary i Taukei communities.

The installation of the latest Tui Nadi is a case that will have far-reaching implications on the way chiefly authority is conferred within i Taukei society. It raised more than a few eyebrows within the Yavusa of Navatulevu as vanua protocols were, presumably, ignored in favour of religious ones.

Rt Vuniyani subsequently brushed these reservations aside by insisting that since his legitimacy has been legally established and recognised by the state, the specific way he was made a chief is really a matter of personal consideration.

As it turned out, he was anointed to his position as Tui Nadi by several church ministers using a prototype from the Old Testament.

What lies at the heart of this latest undertaking is the friction between the quest to integrate, in this case, Ratu Navuniyani's personal freedom to choose how he is to be installed in his vanua and the prevailing moral order of the same vanua from which he is recognised as a chief. The case for the freedom to choose, in this instance, trumped over the imperatives of the recognised social order. Does that make one a bona fide vanua chief?

My main reservation with this new way of legitimising chiefly authority lies in what I perceive as the latent suppression of the vanua as the exclusive repository of legitimate cultural authority. It disenfranchises groups within the vanua who have been historically tasked with performing certain ceremonial roles in any installation.

These roles are symbolic in that they signify the consensus of the vanua in the making of their chief. It is this symbolism that ties the chief and his/her people in an ancient custom of reciprocity. In a nutshell, the chiefs are made by the people and, thus, are ultimately answerable to them.

Yet, as the Nadi case shows, the preponderance of religious rites over customary ones in vanua installations could spell the disempowerment of the ordinary i Taukei from the making of his/her own chief.

Claiming legitimacy or authority via religious formalities brings to mind that age, in human history, where the divine right of kings was a taken for granted fact. This concept of "divine right" is associated with an overt attempt by ruling families for absolute power over their subjects. It removed the need of the European sovereigns to be accountable for their actions.

Indeed the history of European religio-feudal absolutism is littered with tyrannical accounts of enslavement by kings and cronies who claim, with the backing of the church, that their right to rule is a God-given entitlement. In instances like this, human freedom becomes an exclusive domain of the powerful in society.

The subsequent emergence of new ideologies marked by an avowed refusal to sacrifice personal freedom to political, moral and/or religious expediencies is a direct result of the need to safeguard the general population from the vices of those who wield absolute power in European polities.

If we are to protect our identity as i Taukei people and continue empowering our communities in the future, we could do much worse than heeding the historical lessons above on the corrosive impacts of unbridled power in European feudal societies.

* Dr Tuinawi Rakuita is a lecturer in sociology at USP's School of Social Sciences.