Fijileaks: NIGEL HEALEY was not only giving occasional seminars at the University of Bath in the UK. Both, Healey and Cartmell, were also registered Doctoral Students in Business Administration there. It is quite likely they never met in Bath but once connections were established in Fiji, Healey should have recused himself from chairing the interview, as requested by one of the two local candidates, citing conflict of interest.

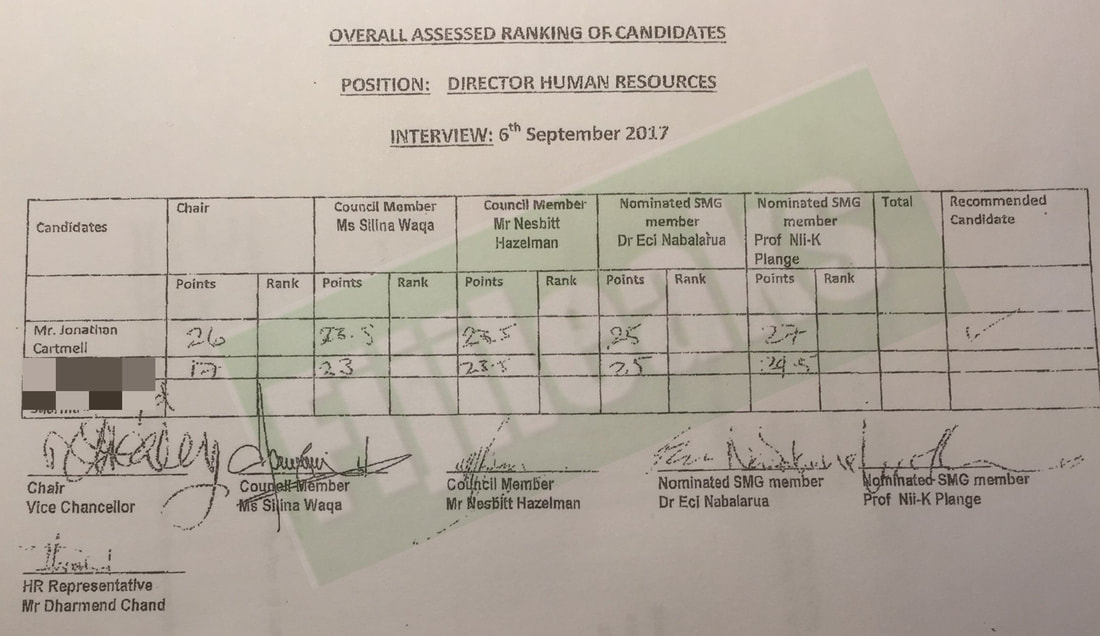

One of the interviewers has told Fijileaks that they were not informed by Healey about the request from one of the two local candidates for an independent panel. According to the panelist Healey had merely scrawled on the score sheet w/d [meaning withdrawn] - against the name of one of the two local candidates, so they proceeded to interview the two remaining candidates, one local and another: CARTMELL

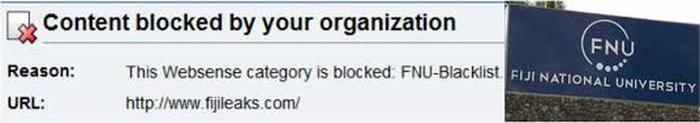

Fijileaks: We call on FICAC to launch a full scale investigation into the Cartmell appointment despite Healey issuing veiled threats to Whistleblowers, claiming the leaks are an abuse of office. We have a formidable track record of being proven correct previously on FNU scandals, and we have more highly explosive materials on Healey and Cartmell but which we will reveal at our own time and choosing. We had spent months investigating Cartmell's appointment before going public!

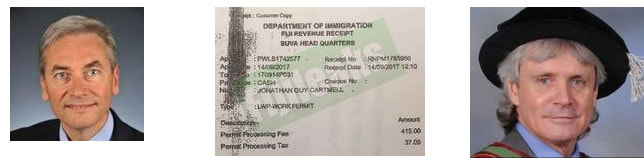

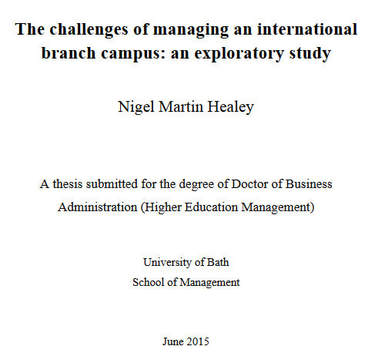

Fijileaks: Both, Healey and Cartmell, were also registered Doctoral Students in Business Administration; Cartmell lists his education affiliation with University of Bath as pending (2014-20). Healey completed his thesis in 2016 from the University of Bath:

Healey, N., 2016. The challenges of managing an international branch campus: An exploratory study. Thesis (Doctor of Business Administration (DBA)), University of Bath. Cartmell's previous employment with Georgetown University was as Executive Director - Office of Outreach and Business Development - for the university's Qatar campus. Healey's thesis is a study of the challenges of managing an international branch campus (IBC) of a UK university. One can see how useful Cartmell's previous employment is to Healey's thesis. Healey is reportedly on $500,000 salary as VC of FNU and Cartmell has been appointed on $300,000

Fijileaks: Jonathan Cartmell should FINISH his thesis, FIRST! But is he still finishing his thesis part-time with the University of Bath, UK?

CRY THE BELOVED COUNTRY!

The following was sent to us with a request to hold back his name:

"With respect to the FNU scandal, I make this observation. VC salary is over $500,000 and the Director HR [Cartmell] was on $250,000. VC Ganesh Chand's salary was $181,000 and Narend Prasad's as Director HR and Director Finance was $150,000 Registrar and Deans salaries ranged between $70,000 to $100,000. So altogether during Ganesh Chand's time the total salary of the VC, Registrar, Director of Finance, Director HR, and four Deans of Colleges, was in total seven senior management positions still below the total salaries of the current VC and his Director of HR.

Can you please not put my name under this post..."

"With respect to the FNU scandal, I make this observation. VC salary is over $500,000 and the Director HR [Cartmell] was on $250,000. VC Ganesh Chand's salary was $181,000 and Narend Prasad's as Director HR and Director Finance was $150,000 Registrar and Deans salaries ranged between $70,000 to $100,000. So altogether during Ganesh Chand's time the total salary of the VC, Registrar, Director of Finance, Director HR, and four Deans of Colleges, was in total seven senior management positions still below the total salaries of the current VC and his Director of HR.

Can you please not put my name under this post..."

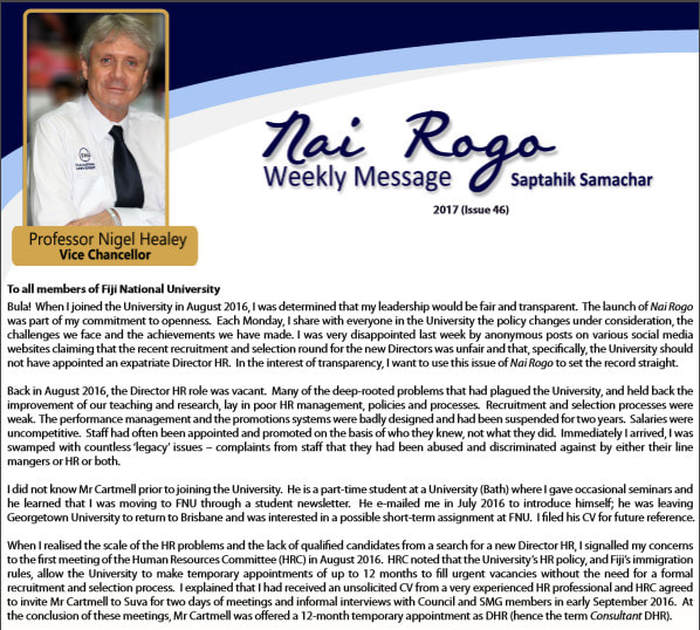

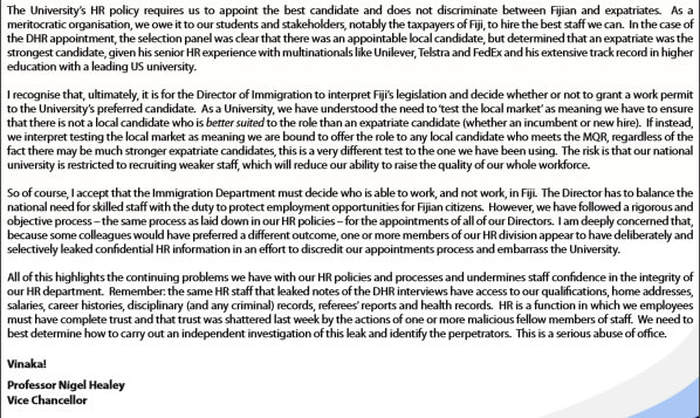

HEALEY circulated this circular below in response to Fijileaks postings

Fijileaks:

* If Healey is so much concerned about the transparency of HR processes at FNU,, especially recruitment and selection, then why didn't he recuse himself from the interview of Director HR when he himself brought in Cartmell as Consultant Director (see Healey's circular, above, to FNU)?

* Why didn't Healey agree to one of the two local candidate's request for an independent panel?

* Why did Healey go ahead and write preferred candidate is Cartmell if he really believes in transparency?

Healey is contradicting himself by writing the attached circular to all FNU.

* Why is Healey comparing the weaker candidate_____ with Cartmell?

* Why not compare Cartmell with ____, the local candidate who was more qualified than Cartmell but who wanted Healey to recuse himself from the interview panel?

"In the case of the DHR appointment, the selection panel was clear that there was an appointable candidate, but determined that an expatriate [Jonathan Cartmell] was the strongest candidate, given his senior HR experience with multinationals like Unilever, Telstra and FedEx and his extensive track record in higher education with a leading US university" -

Nigel Healey in his FNU circular; he was chair of the selection panel, and allegedly refused to recuse himself despite a request from another local candidate who cited conflict of interest, for Healey had hired Cartmell

Fijileaks: Cartmell's CV is not all gold!!!!!!!!!!!!

One of the interviewing panelists has told Fijileaks that they were not informed by Healey about the request from one of the two local candidates for an independent panel. According to the panelist Healey had merely scrawled on the score sheet - withdrawn - against the name of one of the two local candidates, so they proceeded to interview the two remaining candidates, one local and another: CARTMELL

Abstract

This thesis is a study of the challenges of managing an international branch campus (IBC) of a UK university. Branch or satellite campuses are not a new phenomenon. Within the UK, the Universities of Leicester, Nottingham and Southampton all began as university colleges of the University of London, teaching a prescribed curriculum and acting as an examination centre for the University of London. Ironically perhaps, over a century after London provided higher education to the provinces, at least 13 provincial universities currently operate branch campuses in the capital, including Glasgow Caledonian University and the Universities of Liverpool, Cumbria, South Wales and Ulster (Quality Assurance Agency 2014). Internationally, the University of Ceylon (now separated into the Universities of Colombo, Peradeniya, Vidyodaya and Kelaniya) was also set up as an international college of the University of London. After World War II, a number of Commonwealth university colleges of the University of London were established under the ‘scheme of special relationships’. These colleges offered University of London degrees and were provided with academic support to develop their systems and procedures so that they could eventually become independent. The group of Commonwealth colleges in the special relationship included the predecessors of today’s Universities of Ibadan, Nairobi, West Indies and Zimbabwe (Harte 1986). The current wave of IBCs is, however, different from the university colleges of yesteryear in two important respects. First, today’s IBCs are the private initiatives of UK universities, rather than part of a wider development policy agenda driven by the UK or a foreign colonial government. Second, the IBCs are privately owned, either wholly or jointly by the UK universities, rather than being public institutions set up by a government. This is reflected in the titles of the new IBCs which either position them as an extension of the UK university (eg, University of Reading Malaysia, University of Middlesex Dubai) or highlight the nature of the educational partnership (eg, International University of Malaya Wales, Xi’an Jaiotong Liverpool University). The common thread connecting today’s IBCs to the past is that they follow the historical 8 convention of teaching curricula designed in the UK and awarding the degrees of the home university. The 21st century version of the IBC is a relatively recent phenomenon. Prior to the conclusion of the ‘Uruguay Round’ of trade talks and the establishment of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) in 1995, non-tariff barriers effectively precluded trade in educational services in most markets. The oldest ‘modern’ IBC is the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, which was set up in 2000. Most of the UK’s IBC’s have been established only in the last ten years and a number ─ for example, the University of Reading Malaysia and Heriot-Watt University Malaysia ─ are still in their infancy. Building and operating an IBC represents a ‘brave new frontier’ for UK universities and this thesis sheds important light on the challenges involved. The international strategy literature provides a valuable conceptual framework within which to organise these challenges. The globalisation of business is far more advanced than that of higher education and the management models much better understood. Multinational corporations (MNCs) have developed sophisticated techniques for managing extensive networks of overseas subsidiaries and have dedicated functional departments to oversee the movement of labour, goods, services and capital across national borders. A fundamental challenge for MNCs is to determine how much to localise their product or service to meet the needs of each national market. Universities face the same dilemma with their IBCs. Should they be ‘clones’ of the home campus, providing an educational experience which is identical to that on the home campus? Or should they localise the curriculum and pedagogy to adapt to the learning styles and context of the host market? Unlike MNCs, however, UK universities are not huge corporations with HR and finance departments accustomed to dealing with transfer pricing, international tax issues and managing internationally mobile staff. They are stolid, UK-based organisations with a public sector ethos and a tradition of being managed by academics, rather than professional career managers. They are characterised by arcane governance structures, internal politics and glacial decision-making. More than half the UK universities (ie, 9 the former polytechnics and colleges of higher education) have been independent of local government control for less than 25 years and many still operate on the basis of employment contracts and working practices from this era. The scale of the IBCs relative to their UK campuses is, moreover, generally so small that the organisational ‘centre of gravity’ is overwhelmingly the UK-based operation. A second difference between MNCs’ subsidiaries and IBCs is that, despite the advent of GATS, higher education remains a highly regulated sector. UK universities are subject to oversight by the national Higher Education Funding Councils, the Office for Fair Access (OFFA) and the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA). When they establish IBCs which provide UK degrees, the IBCs are subject to the same scrutiny by the QAA. At the same time, IBCs are regulated by the equivalent bodies in the host country, either arms-length organisations like the Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA) or the host Ministry of Education. Governments in many countries subsidise higher education, either indirectly by providing students with grants or loans to contribute towards tuition costs or directly by subsidising universities or operating them as part of the public sector. To control the cost to the taxpayer, they often impose enrolment caps; to meet public good objectives, governments may use a range of levers from moral suasion to purpose-specific grants to steer universities to admit students from underrepresented backgrounds or undertake research in particular areas. At the very least, IBCs must compete with subsidised, regulated local universities, but often they themselves are subject to the same regulation and control. Because of these two important differences between MNCs and universities, the focus of this study is on the challenges of managing an IBC as perceived by the IBC managers. While there is a well-developed literature on principal-agent theory, much of the international strategy literature on localisation approaches the problem from an organisational perspective; that is, it couches the challenge to the MNC as an entity of determining the optimal degree of localisation. In the case of an IBC, the senior management of the home university may similarly take a view, in principle, of the optimal degree of localisation of the curriculum. But because the management systems of a UK university are so underdeveloped in terms of controlling a small IBC thousands of kilometres away, and because there are other equally powerful stakeholders in the 10 host country involved, it is the IBC manager in situ who has to balance these competing demands. This study uses critical realism as the conceptual framework. This is because IBC managers are operating in the context of hard objective, external facts (government regulations, enrolment targets, financial budgets), but they nevertheless have to construct their own understanding of their objectives within the context of the wider social structures and power relations. For IBC managers, they are working in an alien culture where they may not speak the local language or fully comprehend the social norms and conventions. They have to work out what they think are the agendas of the host government, their joint venture partner and their competitors and what they believe their students want. They also have to interpret the home university’s objectives, which may be vague or ambiguous given the differing objectives of the most senior leaders (eg, the pro vice-chancellor teaching and learning is likely to take a different view from the chief financial officer about the objectives of the IBC) and the shifting political alliances in the senior management team. Using semi-structured interviews with IBC managers, mostly in their own offices at the IBC, this thesis finds that the managers feel pressure to localise the staff base, the curriculum (broadly defined to embrace content, pedagogy and assessment) and research. This pressure emanates from five main clusters of stakeholders: the home university, the joint venture partner, the host country (government, regulators and employers), competitors and students. The importance of the focus on the IBC managers is that, firstly, they generally report that the senior management of the home university typically exercises limited direct control, failing to understand the situation on the ground or making decisions in an ad hoc, sometimes contradictory way; in no case did any IBC manager report that they felt there was a clear strategic vision on the part of the home university management team for the development of the IBC. Second, the IBC managers are constantly encountering novel problems or issues that neither they, nor their senior colleagues at the home university, have ever encountered before and they have to use their judgement to achieve a resolution. 11 The analysis of the qualitative data shows that the global integration (I) – local responsiveness (R) paradigm represents a tractable framework for organising the dimensions of the IBC which may be localised to a greater or lesser extent. Further analysis of the objectives of the stakeholders suggests that IBC managers are generally driven to a high degree of localisation of the staff base, while experiencing considerable resistance to the localisation of the curriculum. Whether or not research is localised depends on the extent to which the priorities of the host country reflect wider international concerns (eg, climate change, energy sustainability).

This thesis is a study of the challenges of managing an international branch campus (IBC) of a UK university. Branch or satellite campuses are not a new phenomenon. Within the UK, the Universities of Leicester, Nottingham and Southampton all began as university colleges of the University of London, teaching a prescribed curriculum and acting as an examination centre for the University of London. Ironically perhaps, over a century after London provided higher education to the provinces, at least 13 provincial universities currently operate branch campuses in the capital, including Glasgow Caledonian University and the Universities of Liverpool, Cumbria, South Wales and Ulster (Quality Assurance Agency 2014). Internationally, the University of Ceylon (now separated into the Universities of Colombo, Peradeniya, Vidyodaya and Kelaniya) was also set up as an international college of the University of London. After World War II, a number of Commonwealth university colleges of the University of London were established under the ‘scheme of special relationships’. These colleges offered University of London degrees and were provided with academic support to develop their systems and procedures so that they could eventually become independent. The group of Commonwealth colleges in the special relationship included the predecessors of today’s Universities of Ibadan, Nairobi, West Indies and Zimbabwe (Harte 1986). The current wave of IBCs is, however, different from the university colleges of yesteryear in two important respects. First, today’s IBCs are the private initiatives of UK universities, rather than part of a wider development policy agenda driven by the UK or a foreign colonial government. Second, the IBCs are privately owned, either wholly or jointly by the UK universities, rather than being public institutions set up by a government. This is reflected in the titles of the new IBCs which either position them as an extension of the UK university (eg, University of Reading Malaysia, University of Middlesex Dubai) or highlight the nature of the educational partnership (eg, International University of Malaya Wales, Xi’an Jaiotong Liverpool University). The common thread connecting today’s IBCs to the past is that they follow the historical 8 convention of teaching curricula designed in the UK and awarding the degrees of the home university. The 21st century version of the IBC is a relatively recent phenomenon. Prior to the conclusion of the ‘Uruguay Round’ of trade talks and the establishment of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) in 1995, non-tariff barriers effectively precluded trade in educational services in most markets. The oldest ‘modern’ IBC is the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, which was set up in 2000. Most of the UK’s IBC’s have been established only in the last ten years and a number ─ for example, the University of Reading Malaysia and Heriot-Watt University Malaysia ─ are still in their infancy. Building and operating an IBC represents a ‘brave new frontier’ for UK universities and this thesis sheds important light on the challenges involved. The international strategy literature provides a valuable conceptual framework within which to organise these challenges. The globalisation of business is far more advanced than that of higher education and the management models much better understood. Multinational corporations (MNCs) have developed sophisticated techniques for managing extensive networks of overseas subsidiaries and have dedicated functional departments to oversee the movement of labour, goods, services and capital across national borders. A fundamental challenge for MNCs is to determine how much to localise their product or service to meet the needs of each national market. Universities face the same dilemma with their IBCs. Should they be ‘clones’ of the home campus, providing an educational experience which is identical to that on the home campus? Or should they localise the curriculum and pedagogy to adapt to the learning styles and context of the host market? Unlike MNCs, however, UK universities are not huge corporations with HR and finance departments accustomed to dealing with transfer pricing, international tax issues and managing internationally mobile staff. They are stolid, UK-based organisations with a public sector ethos and a tradition of being managed by academics, rather than professional career managers. They are characterised by arcane governance structures, internal politics and glacial decision-making. More than half the UK universities (ie, 9 the former polytechnics and colleges of higher education) have been independent of local government control for less than 25 years and many still operate on the basis of employment contracts and working practices from this era. The scale of the IBCs relative to their UK campuses is, moreover, generally so small that the organisational ‘centre of gravity’ is overwhelmingly the UK-based operation. A second difference between MNCs’ subsidiaries and IBCs is that, despite the advent of GATS, higher education remains a highly regulated sector. UK universities are subject to oversight by the national Higher Education Funding Councils, the Office for Fair Access (OFFA) and the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA). When they establish IBCs which provide UK degrees, the IBCs are subject to the same scrutiny by the QAA. At the same time, IBCs are regulated by the equivalent bodies in the host country, either arms-length organisations like the Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA) or the host Ministry of Education. Governments in many countries subsidise higher education, either indirectly by providing students with grants or loans to contribute towards tuition costs or directly by subsidising universities or operating them as part of the public sector. To control the cost to the taxpayer, they often impose enrolment caps; to meet public good objectives, governments may use a range of levers from moral suasion to purpose-specific grants to steer universities to admit students from underrepresented backgrounds or undertake research in particular areas. At the very least, IBCs must compete with subsidised, regulated local universities, but often they themselves are subject to the same regulation and control. Because of these two important differences between MNCs and universities, the focus of this study is on the challenges of managing an IBC as perceived by the IBC managers. While there is a well-developed literature on principal-agent theory, much of the international strategy literature on localisation approaches the problem from an organisational perspective; that is, it couches the challenge to the MNC as an entity of determining the optimal degree of localisation. In the case of an IBC, the senior management of the home university may similarly take a view, in principle, of the optimal degree of localisation of the curriculum. But because the management systems of a UK university are so underdeveloped in terms of controlling a small IBC thousands of kilometres away, and because there are other equally powerful stakeholders in the 10 host country involved, it is the IBC manager in situ who has to balance these competing demands. This study uses critical realism as the conceptual framework. This is because IBC managers are operating in the context of hard objective, external facts (government regulations, enrolment targets, financial budgets), but they nevertheless have to construct their own understanding of their objectives within the context of the wider social structures and power relations. For IBC managers, they are working in an alien culture where they may not speak the local language or fully comprehend the social norms and conventions. They have to work out what they think are the agendas of the host government, their joint venture partner and their competitors and what they believe their students want. They also have to interpret the home university’s objectives, which may be vague or ambiguous given the differing objectives of the most senior leaders (eg, the pro vice-chancellor teaching and learning is likely to take a different view from the chief financial officer about the objectives of the IBC) and the shifting political alliances in the senior management team. Using semi-structured interviews with IBC managers, mostly in their own offices at the IBC, this thesis finds that the managers feel pressure to localise the staff base, the curriculum (broadly defined to embrace content, pedagogy and assessment) and research. This pressure emanates from five main clusters of stakeholders: the home university, the joint venture partner, the host country (government, regulators and employers), competitors and students. The importance of the focus on the IBC managers is that, firstly, they generally report that the senior management of the home university typically exercises limited direct control, failing to understand the situation on the ground or making decisions in an ad hoc, sometimes contradictory way; in no case did any IBC manager report that they felt there was a clear strategic vision on the part of the home university management team for the development of the IBC. Second, the IBC managers are constantly encountering novel problems or issues that neither they, nor their senior colleagues at the home university, have ever encountered before and they have to use their judgement to achieve a resolution. 11 The analysis of the qualitative data shows that the global integration (I) – local responsiveness (R) paradigm represents a tractable framework for organising the dimensions of the IBC which may be localised to a greater or lesser extent. Further analysis of the objectives of the stakeholders suggests that IBC managers are generally driven to a high degree of localisation of the staff base, while experiencing considerable resistance to the localisation of the curriculum. Whether or not research is localised depends on the extent to which the priorities of the host country reflect wider international concerns (eg, climate change, energy sustainability).

Fijileaks: More to follow in coming days

1st August, 2017

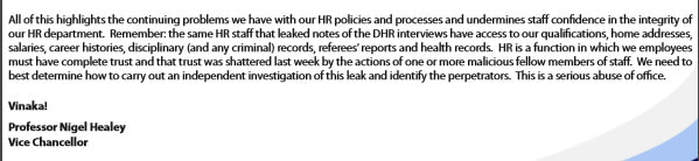

The Director

Department of Immigration

Suva

This is a formal complaint against FNU Consultant Director Human Resources - Mr Jonathan Cartmell.

1. The Director Human Resources position was advertised in 2016. However without any formal interview, Consultant Director - Jonathan Cartmell - was hired by Vice Chancellor - Nigel Healey. The Immigration Department was informed that since FNU could not attract any local staff for Director HR position, FNU had to recruit an expatriate as Consultant Director HR. How can anyone decide on this when the Director position never went through the interview process. The position was advertised, file was made, however the file was put on hold and CDHR was appointed without even testing the local market.

2. The Immigration Department was informed that Consultant Director HR was hired just to train Manager HR and all section Managers and then after 1 year, new local Director HR will be hired. Mr Cartwell's contract is expiring in October 2017. The position has been advertised (June 2017) and there are locals who meet the MQR and can perform the same job at a lower salary thus saving tax payers money.

3. Mr Cartmell is being paid almost $250,000 as Consultant Director HR where else the same tasks can be managed by a local at $80,00.

4. Currently most of the time CDHR is away overseas, mostly travels overseas since his family is in Australia. He himself is very incompetent. Most of his work load is managed by Manager Human resources - Mr_______and section managers.

5. VC and DHR are very close friends and it seems like Director HR position will be given to Mr Cartmell without giving opportunity to the local staff. They are always spotted together having lunch and dinner usually in isolation. Why is there discrimination? I hope Immigration Department does a proper investigation so that justice prevails for Fiji Citizens. As soon as Mr Cartmell joined FNU, he initiated Job Evaluation Exercise which was a total failure. According to him, a person joining recently can perform much better than persons working for years. He himself is new and that is the reason he keeps saying that experienced staff are incompetent which is not correct. He wants to remove all HR staff and bring in his people to work for HR Department.

6. He has approached FNU management to restructure HR department HR Department. If Mr Cartmell wants to minimize costs and restructure FNU management, why was there a need to create Senior Manager HR position when Manager HR position exists? Manager HR, a local staff has also applied for Director HR position. Mr Cartmell quickly created Senior Manager HR position so that this position goes to Manager HR and keeps his mouth shut and gets the Director HR position. If not then he can appoint a new staff for Senior Manager HR and redundant Manager HR position.

7. I hope your team [will] please investigate and let the true picture exposed and [Fijian] taxpayers money is saved from this type of expatriate. Competent staff at FNU are being sidelined in the name of restructure and all is not well. People working in FNU are being used and graded second class employee and making room available for his own colleagues to come on board. It must be seriously noted that he already plans to stay much longer at FNU. Well, this I think was already planned before he was recruited as consultant.

8. This abuse of office and corruption should stop at FNU and I am quite confident your highest office will look at it.

From Whistleblower

cc. FICAC

"He (a highly qualified local candidate whose name Fijileaks is withholding) even told VC [Nigel Healey] to set up an independent interview panel so that fair interview is being held. VC did not agree to _____'s suggestion of conducting a fair interview process...VC went ahead with the interview. Mr Cartmell's CV at the interview was introduced by VC..."

FNU Whistleblower to FICAC, 19 September 201719th September 2017

The Director

Fiji Independent Commission Against Corruption (FICAC)

Suva

Re: CORRUPTION AT FNU HR DEPARTMENT

This is to formally advise on the corrupt practice at Fiji national University. This is mainly related to appointment of Director Human Resources recently. Mr Jonathan Cartmell was hired by VC [Nigel Healey] as consultant Director Human Resources October last year.

1. He was hired on the basis that he would come and train all HR staff and in that process a new full time Director would be appointed and he would be a local based staff. This has been reported to Director Immigration dated 1st August 2017. Also attaching one for your reference. The attached letter was also sent previously but no action has been taken so far. (http://www.fijileaks.com/home/fnugate-fnu-whistleblower-to-immigration-department-the-director-human-resources-position-was-advertised-in-2016-however-without-any-formal-interview-consultant-director-cartmell-was-appointed-by-the-vc)

2. From the information that we have gathered is that Mr Cartmell has been given an offer as Director Human resources with a salary package of $300,000. This has not gone through the Council and the Senior Management Group of FNU. With this amount of salary, three Directors can be hired - local based. It seems like that the interview panel have been forced by Vice Chancellor to conduct interview of Director Human resources position.

3. The two panel members initially had declined to proceed with the interview since there were only two applicants and the position was not internationally advertised. There were only three applicants (the list is attached).

4. The person most capable was a local based staff (__________). who did not attend the interview since he became aware of VC's motive to hire Mr Cartmell. He even told VC to set up an independent interview panel so that fair interview is being held. He knew very well that how ever excellent he performs in the interview, Mr Cartmell will get the position.

5. _______ is the ____________of FNU and he is also ____________. VC did not agree to ________'s suggestion of FNU conducting a fair interview process. He knew very well that ________would point out the blunder that Mr Cartmell has created in the Job Evaluation Exercise. Please also contact________and he can point out what all went wrong with the Job Evaluation Exercise.

6. To avoid this being discussed in the interview, VC went ahead with the interview. VC knew very well that the other applicant ___________is not capable and the panel will obviously give less points so that he is not selected.

7._________. Please provides JUSTICE to local staff of Fiji.

cc:

Minister of Labour

Prime Minister's Office

Higher Salaries Commission

Minister for Education

The Director

Department of Immigration

Suva

This is a formal complaint against FNU Consultant Director Human Resources - Mr Jonathan Cartmell.

1. The Director Human Resources position was advertised in 2016. However without any formal interview, Consultant Director - Jonathan Cartmell - was hired by Vice Chancellor - Nigel Healey. The Immigration Department was informed that since FNU could not attract any local staff for Director HR position, FNU had to recruit an expatriate as Consultant Director HR. How can anyone decide on this when the Director position never went through the interview process. The position was advertised, file was made, however the file was put on hold and CDHR was appointed without even testing the local market.

2. The Immigration Department was informed that Consultant Director HR was hired just to train Manager HR and all section Managers and then after 1 year, new local Director HR will be hired. Mr Cartwell's contract is expiring in October 2017. The position has been advertised (June 2017) and there are locals who meet the MQR and can perform the same job at a lower salary thus saving tax payers money.

3. Mr Cartmell is being paid almost $250,000 as Consultant Director HR where else the same tasks can be managed by a local at $80,00.

4. Currently most of the time CDHR is away overseas, mostly travels overseas since his family is in Australia. He himself is very incompetent. Most of his work load is managed by Manager Human resources - Mr_______and section managers.

5. VC and DHR are very close friends and it seems like Director HR position will be given to Mr Cartmell without giving opportunity to the local staff. They are always spotted together having lunch and dinner usually in isolation. Why is there discrimination? I hope Immigration Department does a proper investigation so that justice prevails for Fiji Citizens. As soon as Mr Cartmell joined FNU, he initiated Job Evaluation Exercise which was a total failure. According to him, a person joining recently can perform much better than persons working for years. He himself is new and that is the reason he keeps saying that experienced staff are incompetent which is not correct. He wants to remove all HR staff and bring in his people to work for HR Department.

6. He has approached FNU management to restructure HR department HR Department. If Mr Cartmell wants to minimize costs and restructure FNU management, why was there a need to create Senior Manager HR position when Manager HR position exists? Manager HR, a local staff has also applied for Director HR position. Mr Cartmell quickly created Senior Manager HR position so that this position goes to Manager HR and keeps his mouth shut and gets the Director HR position. If not then he can appoint a new staff for Senior Manager HR and redundant Manager HR position.

7. I hope your team [will] please investigate and let the true picture exposed and [Fijian] taxpayers money is saved from this type of expatriate. Competent staff at FNU are being sidelined in the name of restructure and all is not well. People working in FNU are being used and graded second class employee and making room available for his own colleagues to come on board. It must be seriously noted that he already plans to stay much longer at FNU. Well, this I think was already planned before he was recruited as consultant.

8. This abuse of office and corruption should stop at FNU and I am quite confident your highest office will look at it.

From Whistleblower

cc. FICAC

"He (a highly qualified local candidate whose name Fijileaks is withholding) even told VC [Nigel Healey] to set up an independent interview panel so that fair interview is being held. VC did not agree to _____'s suggestion of conducting a fair interview process...VC went ahead with the interview. Mr Cartmell's CV at the interview was introduced by VC..."

FNU Whistleblower to FICAC, 19 September 201719th September 2017

The Director

Fiji Independent Commission Against Corruption (FICAC)

Suva

Re: CORRUPTION AT FNU HR DEPARTMENT

This is to formally advise on the corrupt practice at Fiji national University. This is mainly related to appointment of Director Human Resources recently. Mr Jonathan Cartmell was hired by VC [Nigel Healey] as consultant Director Human Resources October last year.

1. He was hired on the basis that he would come and train all HR staff and in that process a new full time Director would be appointed and he would be a local based staff. This has been reported to Director Immigration dated 1st August 2017. Also attaching one for your reference. The attached letter was also sent previously but no action has been taken so far. (http://www.fijileaks.com/home/fnugate-fnu-whistleblower-to-immigration-department-the-director-human-resources-position-was-advertised-in-2016-however-without-any-formal-interview-consultant-director-cartmell-was-appointed-by-the-vc)

2. From the information that we have gathered is that Mr Cartmell has been given an offer as Director Human resources with a salary package of $300,000. This has not gone through the Council and the Senior Management Group of FNU. With this amount of salary, three Directors can be hired - local based. It seems like that the interview panel have been forced by Vice Chancellor to conduct interview of Director Human resources position.

3. The two panel members initially had declined to proceed with the interview since there were only two applicants and the position was not internationally advertised. There were only three applicants (the list is attached).

4. The person most capable was a local based staff (__________). who did not attend the interview since he became aware of VC's motive to hire Mr Cartmell. He even told VC to set up an independent interview panel so that fair interview is being held. He knew very well that how ever excellent he performs in the interview, Mr Cartmell will get the position.

5. _______ is the ____________of FNU and he is also ____________. VC did not agree to ________'s suggestion of FNU conducting a fair interview process. He knew very well that ________would point out the blunder that Mr Cartmell has created in the Job Evaluation Exercise. Please also contact________and he can point out what all went wrong with the Job Evaluation Exercise.

6. To avoid this being discussed in the interview, VC went ahead with the interview. VC knew very well that the other applicant ___________is not capable and the panel will obviously give less points so that he is not selected.

7._________. Please provides JUSTICE to local staff of Fiji.

cc:

Minister of Labour

Prime Minister's Office

Higher Salaries Commission

Minister for Education